22. 7-day diagnostic radiology

22.1. Introduction

Diagnostic radiology plays a crucial role in the clinical assessment of patients with acute medical emergencies (AME); for example, a chest x-ray (CXR) can provide information in patients presenting with chest pain or shortness of breath that influences diagnosis and immediate management. More sophisticated radiological investigations such as computerised tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound (US) and ventilation perfusion (V/Q) scans can also provide important information in patients with AME across a spectrum of presenting complaints. There are certain specific conditions (for example, pulmonary embolism, acute stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cauda equina syndrome or thoracic dissection) that require urgent radiology (for example, CT or MRI) to determine the need for certain critical interventions (for example, thrombolysis, blood pressure control or surgery).

While it would seem inconceivable that access to basic radiology (for example, CXR) could be anything other than universal in a hospital setting, it remains unclear whether such access to all diagnostic radiological services is clinically or cost effective. There is a strategic drive in the United Kingdom NHS to provide a seven day service with the aspiration of equality of access to high quality medical care throughout the week. The provision of a 7-day diagnostic service has been identified by NHS England as being crucial to all elements of patient care22 and the Royal College of Radiologists has produced standards for providing a 7-day service.30 There is also existing NICE guidance on specific conditions that would require a 7-day diagnostic service to be present (for example, diagnosis of stroke, head injury and deep vein thrombosis).

Currently there is variable access to diagnostic radiology both in terms of time of the day, day of the week and geographical location, with larger centres tending to provide better access. Whilst plain radiology (for example, a CXR) is, as stated above, universally available in all EDs at all times of the day and days of the week, access to more sophisticated radiology (for example, CT, MRI, US) varies enormously by time of day, day of week and even geographical location. Specifically, for example, some EDs will have access to CT scanning during the day but not at night, or to US scanning during the week but not at weekend; geographical networks may be in place to allow access to certain investigations in certain places which are not available at others.

Given this lack of consistency in access to diagnostic radiology, the guideline committee aimed to address the question “does the provision of seven day diagnostic radiology in hospital improve patient outcomes?” in order to help inform the configuration of seven day services in the NHS.

22.2. Review question: Does the provision of 7 day diagnostic radiology in hospital improve patient outcomes?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

22.3. Clinical evidence

No relevant clinical studies comparing 24 hour access to diagnostic radiology with reduced access to diagnostic radiology were identified.

22.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

In the absence of health economic evidence, unit costs were presented to the committee – see Chapter 41 Appendix I.

22.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

- No relevant clinical studies were identified.

Economic

- No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

22.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

References

- 1.

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Seven day consultant present care: implementation considerations, 2013. Available from: http://www

.aomrc.org .uk/publications/reports-guidance /seven-day-implementation-considerations-1113/ - 2.

- Al Wattar BH, Frank M, Fage E, Gupta P. Use of ultrasound in emergency gynaecology. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2014; 34(2):172–173 [PubMed: 24456441]

- 3.

- Arnaoutakis GJ, Pirrucello J, Brooke BS, Reifsnyder T. Venous duplex scanning for suspected deep vein thrombosis: results before and after elimination of after-hours studies. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2010; 44(5):329–333 [PubMed: 20484080]

- 4.

- Berner ES, Baker CS, Funkhouser E, Heudebert GR, Allison JJ, Fargason J et al. Do local opinion leaders augment hospital quality improvement efforts? A randomized trial to promote adherence to unstable angina guidelines. Medical Care. 2003; 41(3):420–431 [PubMed: 12618645]

- 5.

- Burton KR, Lawlor RL, Dhanoa D. The impact of a preauthorization policy on the after-hours utilization of emergency department computed tomography imaging. Academic Radiology. 2016; 23(5):588–591 [PubMed: 26947223]

- 6.

- Campbell JTP, Bray BD, Hoffman AM, Kavanagh SJ, Rudd AG, Tyrrell PJ et al. The effect of out of hours presentation with acute stroke on processes of care and outcomes: analysis of data from the Stroke Improvement National Audit Programme (SINAP). PloS One. 2014; 9(2):e87946 [PMC free article: PMC3922754] [PubMed: 24533063]

- 7.

- Carlos RC, Goeree R. Introduction: health technology assessment in diagnostic imaging. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2009; 6(5):297–298 [PubMed: 19394569]

- 8.

- Chana P, Burns EM, Arora S, Darzi AW, Faiz OD. A systematic review of the impact of dedicated emergency surgical services on patient outcomes. Annals of Surgery. 2016; 263(1):20–27 [PubMed: 26840649]

- 9.

- Cubeddu RJ, Palacios IF, Blankenship JC, Horvath SA, Xu K, Kovacic JC et al. Outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention during on- versus off-hours (a Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI] trial substudy). American Journal of Cardiology. 2013; 111(7):946–954 [PubMed: 23340031]

- 10.

- Ebinger M, Rozanski M, Waldschmidt C, Weber J, Wendt M, Winter B et al. PHANTOM-S: the prehospital acute neurological therapy and optimization of medical care in stroke patients - study. International Journal of Stroke. 2012; 7(4):348–353 [PubMed: 22300008]

- 11.

- Hardy M, Hutton J, Snaith B. Is a radiographer led immediate reporting service for emergency department referrals a cost effective initiative? Radiography. 2013; 19(1):23–27

- 12.

- Jamal K, Mandel L, Jamal L, Gilani S. ‘Out of hours’ adult CT head interpretation by senior emergency department staff following an intensive teaching session: a prospective blinded pilot study of 405 patients. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2014; 31(6):467–470 [PubMed: 23576233]

- 13.

- Khoo NC, Duffy M. ‘Out of hours’ non-contrast head CT scan interpretation by senior emergency department medical staff. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2007; 19(2):122–128 [PubMed: 17448097]

- 14.

- Langan EM, Coffey CB, Taylor SM, Snyder BA, Sullivan TM, Cull DL et al. The impact of the development of a program to reduce urgent (off-hours) venous duplex ultrasound scan studies. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2002; 36(1):132–136 [PubMed: 12096270]

- 15.

- Miller CD, Hoekstra JW, Lefebvre C, Blumstein H, Hamilton CA, Harper EN et al. Provider-directed imaging stress testing reduces health care expenditures in lower-risk chest pain patients presenting to the emergency department. Circulation Cardiovascular Imaging. 2012; 5(1):111–118 [PMC free article: PMC3272279] [PubMed: 22128195]

- 16.

- Moss JG, Murchison JT. Is radiology a ‘nine to five’ specialty? Clinical Radiology. 1992; 46(2):124–127 [PubMed: 1395400]

- 17.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Venous thromboembolic diseases: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. NICE clinical guideline 144. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2012. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG144 - 18.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. NICE clinical guideline 176. London. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2014. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG176 - 19.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). NICE clinical guideline 68. London. Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Available from: http://guidance

.nice.org.uk/CG68 [PubMed: 21698846] - 20.

- National Imaging Clinical Advisory Group. Implementing 7 Day working inImaging Departments: Good Practice Guidance. Department of Health; 2012. Available from: https://www

.hislac.org /images/docs/policy-library /Implementing %207%20day%20working %20in%20imaging%20department.pdf - 21.

- Ng CS, Watson CJE, Palmer CR, See TC, Beharry NA, Housden BA et al. Evaluation of early abdominopelvic computed tomography in patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown cause: prospective randomised study. BMJ. 2002; 325(7377):1387–1389 [PMC free article: PMC138513] [PubMed: 12480851]

- 22.

- NHS England. NHS Services, Seven Days a Week Forum, 2013. Available from: https://www

.england.nhs .uk/wp-content/uploads /2013/12/forum-summary-report.pdf - 23.

- Notghi A, Mills AP, Harding LK. Out-of-hours weekend scintigraphy: assessing/predicting the need. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 1997; 18(9):857–860 [PubMed: 9352553]

- 24.

- Power ML, Cross SP, Roberts S, Tyrrell PJ. Evaluation of a service development to implement the top three process indicators for quality stroke care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007; 13(1):90–94 [PubMed: 17286729]

- 25.

- Raja FS, Amann J. After-hours radiology consultation in an academic setting, 2005-2009. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 2012; 63(3):165–169 [PubMed: 21873025]

- 26.

- Redd V, Levin S, Toerper M, Creel A, Peterson S. Effects of fully accessible magnetic resonance imaging in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2015; 22(6):741–749 [PubMed: 25998846]

- 27.

- Scottish Clinical Imaging Network. Seven Day Working in Imaging in Scotland, 2015. Available from: http://www

.scin.scot .nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads /sites/3/2015/04 /2015-10-28-Recommendations-on-the-Implementation-of-Seven-Day-Working-in-Imaging-in-Scotland-V1 .pdf - 28.

- The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for providing a 24-hour interventional radiology service. London: 2008. Available from: https://www

.rcr.ac.uk /sites/default/files /docs/radiology/pdf /Stand_24hr_IR_provision.pdf - 29.

- The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for providing a 24-hour diagnostic radiology service. London: 2009. Available from: https://www

.rcr.ac.uk /sites/default/files /docs/radiology/pdf /BFCR(09)3_diagnostic24hr.pdf - 30.

- The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for providing a seven-day acute care diagnostic radiology service. London. The Royal College of Radiologists, 2016. Available from: https://www

.rcr.ac.uk /sites/default/files /publication/bfcr1514_seven-day_acute .pdf

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 2

Review protocol: Does the provision of 7 day diagnostic radiology in hospital improve patient outcomes?

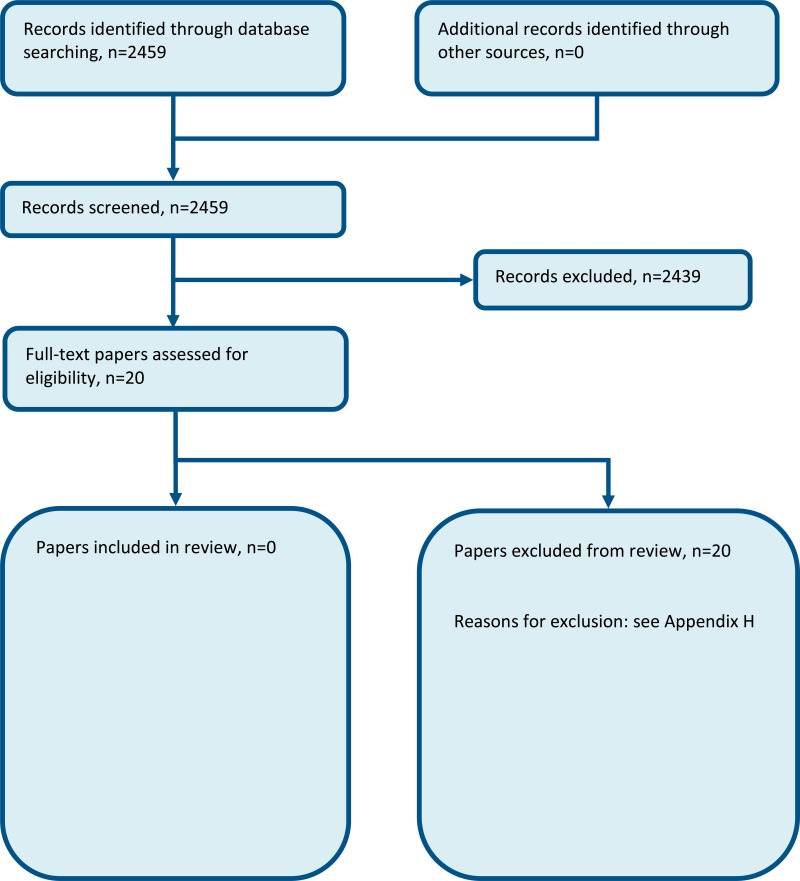

Appendix B. Clinical study selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

No evidence to be included.

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

No evidence to be included.

Appendix E. Health economic evidence tables

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

No evidence to be included.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 3

Studies excluded from the clinical review.

Appendix H. Excluded health economic studies

No health economic studies were excluded.

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), London

NLM Citation

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.) Chapter 22, 7-day diagnostic radiology.