Abstract

The cytosolic proteins EntE, EntF, and EntB/G, which are Escherichia coli enzymes necessary for the final stage of enterobactin synthesis, are released by osmotic shock. Here, consistent with the idea that cytoplasmic proteins found in shockates have an affinity for membranes, a small fraction of each was found in membrane preparations. Two procedures demonstrated that the enzymes were enriched in a minor membrane fraction of buoyant density intermediate between that of cytoplasmic and outer membranes, providing indirect support for the notion that these proteins have a role in enterobactin excretion as well as synthesis.

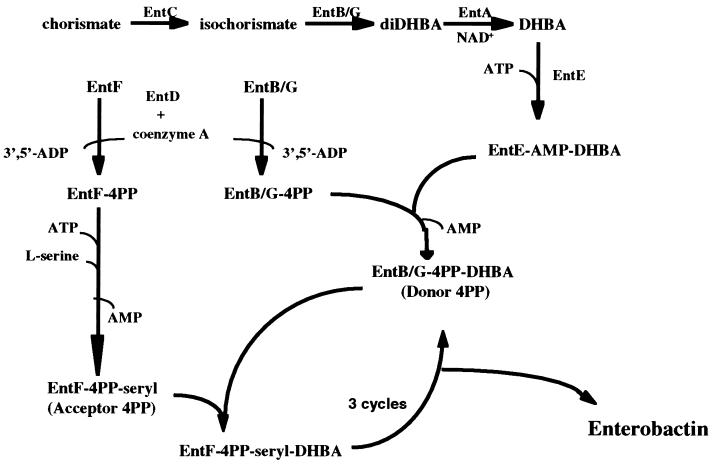

Escherichia coli responds to iron deprivation by synthesizing and excreting a small, iron-chelating molecule termed enterobactin (Ent). Complexes of extracellular Fe(III)-Ent are subsequently transported into the cytoplasm, where Fe(III) is reduced and released from Ent (reviewed in reference 8). The Ent biosynthetic pathway is known (Fig. 1). It has two stages; in the first, chorismate is converted to the specific precursor 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate (DHBA) by the EntC, -B/G and -A proteins, and in the second, three molecules each of DHBA and Ser are converted by EntB/G, -D, -E, and -F to Ent by a protein-thiotemplate mechanism. EntD, a phosphopantetheinyl transferase, posttranslationally modifies both EntB/G and EntF by adding 4′-phosphopantetheine (10, 22). Holo-EntB/G, holo-EntF, and EntE (collectively termed Ent synthase) then catalyze Ent formation (11).

FIG. 1.

Enterobactin biosynthesis. diDHBA, 2,3 dihydro-2,3,dihydroxy benzoic acid; 4PP, 4′-phosphopantetheine.

How siderophores are excreted is a major question in bacterial iron assimilation. Only in Mycobacterium smegmatis, where the exiT gene encodes an ABC transporter that probably functions to pump out exochelin (32), has a secretion component been clearly identified. It was proposed early on that the proteins involved in the second stage of Ent synthesis formed a membrane-associated complex that both synthesized and vectorially transported Ent to the environment (12). This idea, which was supported by chromatographic data showing coelution of some Ent synthase components, was appealing for several reasons, foremost of which was that it provided a means for keeping free Ent from causing damage in the cytoplasm. More recent data, while not eliminating the model, have shown that Ent synthase polypeptides do not form a stable in vitro complex and that a membrane is not necessary for Ent biosynthesis (11, 17).

We demonstrated that the cytoplasmic polypeptides EntE, -F, and -B/G have the unusual trait of being released from cells by osmotic shock but not by conversion of cells to spheroplasts (17). Proteins with this behavior are termed group D proteins (2); in addition to the three Ent proteins, approximately 11 other E. coli proteins can be so classified. The presence of group D proteins in shockates is generally attributed to their loose association with the cytoplasmic membrane (2, 25), and in a preliminary study, EntB/G was detected in membrane preparations (F. Hantash and C. F. Earhart, Abstr. 95th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1995, abstr. K-32, p. 542, 1995). Here the membrane association of EntB/G, -E, and -F was examined in detail. A small portion of each of these proteins was found in membranes, where they were enriched in a fraction intermediate in density between outer and inner membranes.

Association of EntB/G, -E, and -F with membranes.

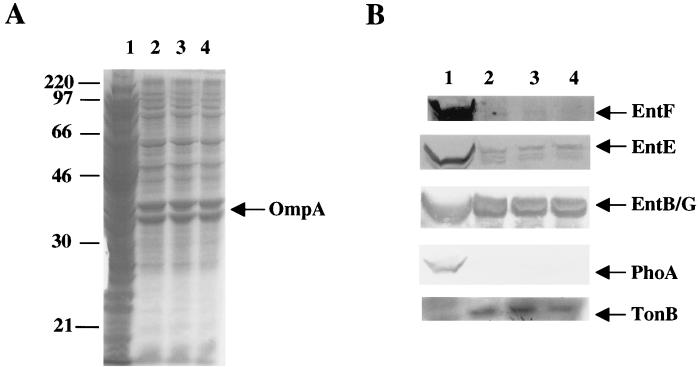

EntE and EntF as well as EntB/G were detected in total membrane preparations from cells grown in iron-deficient medium (TMM) (17) (Fig. 2), but the extent of their membrane association varied significantly. In this and similar experiments (data not shown), EntB/G exhibited the greatest degree of membrane association, followed by EntE and then EntF. Ent synthase proteins in the membrane fractions were firmly attached, as additional washes of the membrane did not result in any dimunition of their presence (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). Periplasmic protein alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) and membrane protein TonB served as controls and were found solely in the soluble and membrane fractions, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Association of EntB/G, EntE, and EntF with membranes. E. coli AB1515 (23) was grown in TMM (17) to 5 × 108 cells/ml, and the total membranes and the soluble protein fractions were isolated. Fractions from equal numbers of cells were examined by Coomassie blue staining (A) and Western blotting (B) after electrophoresis on SDS–11% polyacrylamide gels. Lanes: 1, soluble proteins; 2, total membranes; 3, total membranes after a second wash with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7; 4, total membranes after three washes with buffer.

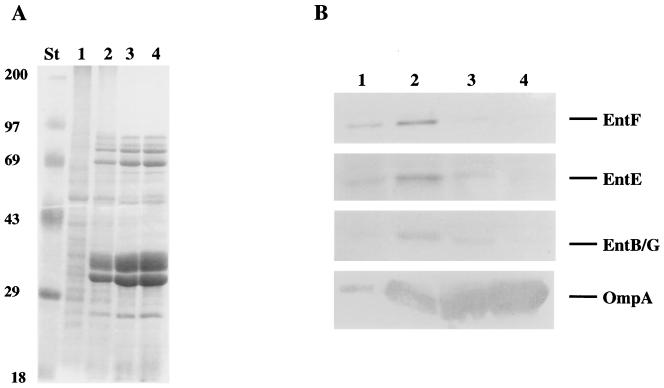

To study the presence of Ent synthase proteins in specific membrane species, membranes from iron-starved cells were fractionated by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation. Both the original procedure (26) and a modification in which membranes float up to their point of equilibrium density were used (27). When membrane species separated by flotation gradients were analyzed (Fig. 3A), membrane-associated Ent synthase proteins were enriched in a fraction intermediate in density between inner membrane and outer membrane (Fig. 3B). Outer membrane protein OmpA served as a control; it was found exclusively in membranes and localized in the outer membrane. PhoA was also monitored by Western blotting and found solely in the soluble fraction (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Association of EntB/G, -E, and -F with membranes. Total membranes were isolated from mid-log-phase E. coli AB1515 by the procedure of Osborn et al. (26). Membranes were resuspended in 65% sucrose, layered with decreasing concentrations of sucrose solutions (56, 53, 50, 47, 44, 41, 38, 35, and 28%), and separated as described by Poquet et al. (27). Membrane fractions were pooled, and 20 μg of protein (4) from each pool was analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (A) and Western blotting (B) after electrophoresis on 11% polyacrylamide gels (17). Lanes: 1, inner membrane fractions; 2, intermediate-density fractions; 3, light outer membrane fractions; 4, heavy outer membrane fractions; St, molecular weight standards.

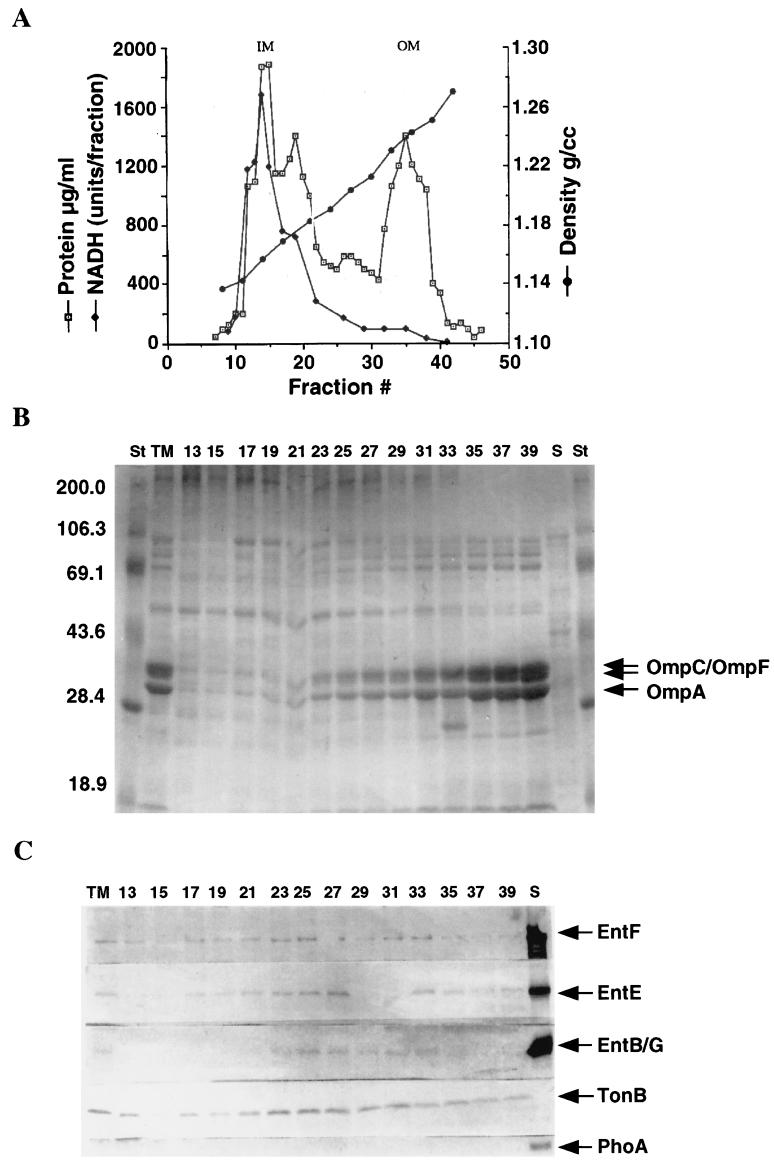

Subsequently, a series of individual fractions from both separation procedures was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. Both procedures gave similar results, and only the data for the method of separation of Osborn et al. (26) are shown (Fig. 4). When equal amounts of protein from each fraction were examined, EntB/G, -E, and -F were again observed to be enriched in membranes of intermediate density (Fig. 4C, fractions 21 to 31); the average density of these membrane fractions for both separation procedures was about 1.19. Figures 4A and B provide the information (density, NADH oxidase activity, porin, and OmpA localization) verifying that the separation of inner and outer membranes was satisfactory. No proteins unique to the intermediate-density membrane were detected by staining (Fig. 4B). The energy-coupling protein TonB was also enriched in the intermediate-density membrane, although TonB clearly differed from group D proteins in that it was present exclusively in membranes (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Presence of EntB/G, -E, and -F in various gradient fractions. Sucrose gradient centrifugation was performed by the method of Osborn et al. (26). Two hundred and fifty-microliter fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and analyzed for protein content, sucrose density, and NADH oxidase activity (units of activity are micromoles of NADH oxidized per minute. (A) Protein content, sucrose density, and NADH oxidase activity of fractions. Equal amounts of protein from various fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by staining and Western blotting. (B) Coomassie blue-stained gel of the various fractions. St, molecular mass standards. Numbers on the side indicate positions of molecular mass standards in kilodaltons. Numbers at the top indicate fraction numbers from panel A. TM, total membrane fraction; S, soluble fraction; (C) Western blot analyses of EntB/G, -E, and -F, TonB, and PhoA. Numbers at the top indicate fraction numbers from panel A. TM, total membrane fraction; S, soluble fraction.

To test the possibility that the majority of EntB/G, -E, and -F are exposed in the periplasm in vivo, cells were converted to spheroplasts (21) and treated with trypsin. No digestion of any Ent synthase polypeptide was detected, while TonB, which has periplasmic exposure, was completely cleaved (data not shown).

Compartmentalization and localization at contact sites between inner and outer membrane.

Currently, the behavior of group D proteins is generally attributed to their positioning at adhesion sites between inner and outer membranes (1, 9, 25). (The existence of adhesion sites, as distinguished from plasmolysis bays, remains a matter of controversy, however [6].) An additional consideration is that certain exported proteins synthesized without their signal sequence are also released by osmotic shock (3, 7, 30). This led us to suggest that proteins released by osmotic shock but not by spheroplasting have temporary or fragile association with membrane sites at which transmembrane passage occurs (17).

The principal finding of this work, the detection of Ent synthase polypeptides in membrane fractions, is consistent with previous explanations for the shockability of group D proteins. Also, that all Ent synthase components are found in shockates and that a small portion of each can be detected in membranes is the only current support for the idea that Ent synthase functions as a membrane-associated complex. Although only a minor portion of EntB/G, -E, and -F was membrane associated their detection was significant: (i) no trace of soluble proteins such as alkaline phosphatase was found in membranes, despite the use of a sensitive assay, and (ii) intracellular concentrations of Ent synthase proteins were at physiological levels, so artifacts arising from overexpression were not possible. The EntB/G, -E, and -F found with membranes were firmly attached; the membrane isolation procedure included a washing step, and additional washes did not result in the loss of Ent synthase polypeptides. Trypsin susceptibility experiments indicated that if the majority of each polypeptide is membrane associated in vivo, they do not extend through the cytoplasmic membrane. The relative amount of each protein found with membranes varied, with EntB/G having the highest degree of membrane association. EntB/G, of the three Ent synthase polypeptides, is also the one found in the highest percentage in shockates (17).

Membrane localization procedures demonstrated that the Ent synthase proteins were enriched in an intermediate density fraction. The in vivo origin of this membrane species is not known, and it is possible that membranes from several distinct cellular locations could have this density. This fraction is likely to include adhesion zones (19, 25), the membrane domain that binds hemimethylated oriC DNA (5) primarily by SeqA (28, 29), envelope proteins such as TolQ, -R, -A, and -B involved in translocations across the periplasm (13) and the group D protein thioredoxin (25) in addition to EntB/G, -E, and -F. For group D proteins, of course, the vast majority of each is found in soluble fractions. We also show here that the envelope protein TonB (24), when monitored on gels in which a constant amount of protein was present in each lane, also was enriched in the intermediate-density fraction under these growth conditions.

Our current working model regarding Ent synthase compartmentalization and its possible role in Ent excretion is as follows. The totality of results with Ent synthase and other group D proteins suggest that a large fraction of these proteins is in contact with, or in close proximity to, membranes. The proportion of a group D protein detected in membranes depends on the lysis technique used (20). With gentle lysis procedures, 20 to 40% of a group D protein can be detected in membranes (9, 25) whereas with more rigorous procedures such as those used here the percentage in membrane is much less. Minimally, the in vivo amount of such membrane-connected polypeptides, in this case Ent synthase components, would be equivalent to that found in shockates. The nature of this membrane association has not been established but, for Ent synthase proteins, it could be dynamic and involve a variety of interactions such as protein-protein and both weak and strong membrane binding. Regardless of its basis, the association for most of each protein species is sufficiently weak that when extracts are prepared for enzyme assays or protein purification the proteins behave as typical cytoplasmic proteins. If the idea (17) that group D proteins are localized at sites of transmembrane passage is correct, it is likely that Ent synthase is associated with a cytoplasmic membrane pump capable of excreting Ent. Additional evidence (17; F. M. Hantash, unpublished data) that must be considered in any model is that the shockability of Ent synthase proteins is unaffected by the absence of either (i) other Ent synthase proteins or (ii) EnxA, a cytoplasmic membrane protein that recent preliminary evidence (D. N. Sanders, I. G. Hook-Barnard, and M. McIntosh, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. B/D-193, p. 66, 1999) suggests is a pump for Ent excretion. Lastly, there was no periplasmic accumulation of Ent by the E. coli strains used (16). Ent may therefore be secreted directly from its site of synthesis through the envelope to the external milieu.

Because the Ent system is a model for siderophore-mediated iron uptake, these ideas concerning the site of siderophore synthesis and manner of secretion may have general relevance, particularly for siderophores synthesized by a protein-thiotemplate mechanism. Indeed, peculiarities of and difficulties in localization of what are probably siderophore biosynthetic enzymes have been reported (14, 15, 31). Especially relevant is work with Yersinia sp. protein HMWP2, a large iron-regulated protein with domains homologous to EntF, EntE, and EntB/G (14, 17). Trace amounts of HMWP2 were found associated with what was apparently the cytoplasmic membrane. The above ideas regarding the localization and functioning of Ent synthase are similar in several ways to one suggestion made by Guilvout et al. (15) to explain HMWP2 data. It would be of interest to determine if HMWP2 and other enzymes besides EntE, -F, and -B/G that function in nonribosomal peptide synthesis are present in shockates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM47885 from the National Institutes of Health and a research grant award from the University of Texas at Austin.

We thank Kathleen Postle and Ulf Henning for anti-TonB and anti-OmpA antibodies, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer M E, Bayer M H, Lunn C A, Pigiet V P. Association of thioredoxin with the inner membrane and adhesion sites in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2659–2666. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2659-2666.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beacham I R. Periplasmic enzymes in Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Biochem. 1979;10:877–883. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(79)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden G A, Baneyx F, Georgiou G. Abnormal fractionation of β-lactamase in Escherichia coli: evidence for an interaction with the inner membrane in the absence of a leader peptide. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3407–3410. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3407-3410.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborti A, Gunji S, Shakibai N, Cubeddu J, Rothfield L. Characterization of the Escherichia coli membrane domain responsible for binding oriC DNA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7202–7206. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7202-7206.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danese P N, Silhavy T J. Targeting and assembly of periplasmic and outer-membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:59–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derman A I, Puziss J W, Bassford P J, Jr, Beckwith J. A signal sequence is not required for protein export in prlA mutants of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1993;12:879–888. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earhart C F. Uptake and metabolism of iron and molybdenum. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1075–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Yaagoubi A, Kohiyama M, Richarme G. Localization of DnaK (chaperone 70) from Escherichia coli in an osmotic-shock-sensitive compartment of the cytoplasm. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7074–7078. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7074-7078.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gehring A M, Bradley K A, Walsh C T. Enterobactin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: isochorismate lyase (EntB) is a bifunctional enzyme that is phosphopantetheinylated by EntD and then acylated by EntE using ATP and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8495–8503. doi: 10.1021/bi970453p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehring A M, Mori I, Walsh C T. Reconstitution and characterization of the Escherichia coli enterobactin synthetase from EntB, EntE, and EntF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2648–2659. doi: 10.1021/bi9726584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwood K T, Luke R K J. Studies on the enzymatic synthesis of enterochelin in Escherichia coli K-12. Four polypeptides involved in the conversion of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate to enterochelin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;454:285–297. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guihard G, Boulanger P, Benedetti H, Lloubes R, Besnard M, Letellier L. Colicin A and the Tol proteins involved in its translocation are preferentially located in the contact sites between the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5874–5880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilvout I, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Bonnefoy S, Pugsley A P, Carniel E. High-molecular-weight protein 2 of Yersinia enterocolitica is homologous to AngR of Vibrio anguillarum and belongs to a family of proteins involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5488–5504. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5488-5504.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilvout I, Carniel E, Pugsley A P. Yersinia spp. HMWP2, a cytosolic protein with a cryptic internal signal sequence which can promote alkaline phosphatase export. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1780–1787. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1780-1787.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hantash F M. Ph.D. thesis. Austin: The University of Texas at Austin; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hantash F M, Ammerlaan M C, Earhart C F. Enterobactin synthase polypeptides of Escherichia coli are present in an osmotic-shock-sensitive cytoplasmic locality. Microbiology. 1997;143:147–156. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye M, Guthrie J P. A mutation which changes a membrane protein of E. coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;64:957–961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishidate K, Creeger E S, Zrike J, Deb S, Glauner B, MacAlister T J, Rothfield L I. Isolation of differentiated membrane domains from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, including a fraction containing attachment sites between the inner and outer membranes and the murein skeleton of the cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:428–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson G R, Takacs B J, Rosenbusch J P. Properties of a major protein released from Escherichia coli by osmotic shock. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2297–2303. doi: 10.1021/bi00656a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaback H R. Bacterial membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1971;22:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambalot R H, Gehring A M, Flugel R S, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel M A, Reid R, Khosla C, Walsh C T. A new enzyme superfamily—the phosphopantetheinyl transferases. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langman L, Young I G, Frost G E, Rosenberg H, Gibson F. Enterochelin system of iron transport in Escherichia coli: mutations affecting ferric-enterochelin esterase. J Bacteriol. 1972;112:1142–1149. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.3.1142-1149.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letain T E, Postle K. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3331703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunn C A, Pigiet V P. Chemical cross-linking of thioredoxin to hybrid membrane fraction in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:832–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osborn M J, Gander J E, Parisi E, Carson J. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3962–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poquet I, Kornacker M G, Pugsley A. The role of the lipoprotein sorting signal (aspartate +2) in pullulanase secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1061–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shakibai N, Ishidate K, Reshetnyak E, Gunji S, Kohiyama M, Rothfield L. High-affinity binding of hemimethylated oriC by Escherichia coli membranes is mediated by a multiprotein system that includes SeqA and a newly identified factor, SeqB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11117–11121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slater S, Wold S, Lu M, Boye E, Skarstad K, Kleckner N. E. coli SeqA protein binds oriC in two different methyl-modulated reactions appropriate to its roles in DNA replication initiation and origin sequestration. Cell. 1995;82:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorstenson Y R, Zhang Y, Olson P S, Mascarenhas D. Leaderless polypeptides extracted from whole cells by osmotic shock. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5333–5339. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5333-5339.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viswanatha T, Szezepan E W, Murray G J. Biosynthesis of aerobactin: enzymological and mechanistic studies. In: Winkelman G, van der Helm D, Neilands J B, editors. Iron transport in microbes, plants and animals. Weinheim, Germany: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft; 1987. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu W, Arceneaux J E L, Beggs M L, Byers B R, Eisenach K D, Lundrigan M D. Exochelin genes in Mycobacterium smegmatis: identification of an ABC transporter and two non-ribosomal peptide synthetase genes. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:629–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]