Significance

Circadian clocks reside in each cell level throughout the body in mammals. Intrinsic cellular circadian clocks develop cell autonomously during the cellular differentiation process. However, mechanisms controlling the emergence of cellular circadian clock oscillation in vivo are not fully understood. Here, we show that Dicer/Dgcr8-mediated posttranscriptional mechanisms control the CLOCK protein expression in both mouse fetal hearts and in vitro differentiating ES cells, which contributes to the emergence of circadian clock in mammalian cells. This event occurs after cell lineage determination into hearts or loss of pluripotent stem cell markers in differentiating ES cells, suggesting the cellular differentiation-coupled clock development may be conducted by a two-step program consisting of cellular differentiation and subsequent establishment of circadian transcriptional/translational feedback loops.

Keywords: circadian clock, ontogeny, cellular differentiation, CLOCK, posttranscriptional regulation

Abstract

Circadian clock oscillation emerges in mouse embryo in the later developmental stages. Although circadian clock development is closely correlated with cellular differentiation, the mechanisms of its emergence during mammalian development are not well understood. Here, we demonstrate an essential role of the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock subsequent to the cellular differentiation for the emergence of circadian clock oscillation in mouse fetal hearts and mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs). In mouse fetal hearts, no apparent oscillation of cell-autonomous molecular clock was detectable around E10, whereas oscillation was clearly visible in E18 hearts. Temporal RNA-sequencing analysis using mouse fetal hearts reveals many fewer rhythmic genes in E10–12 hearts (63, no core circadian genes) than in E17–19 hearts (483 genes), suggesting the lack of functional circadian transcriptional/translational feedback loops (TTFLs) of core circadian genes in E10 mouse fetal hearts. In both ESCs and E10 embryos, CLOCK protein was absent despite the expression of Clock mRNA, which we showed was due to Dicer/Dgcr8-dependent translational suppression of CLOCK. The CLOCK protein is required for the discernible molecular oscillation in differentiated cells, and the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock plays a role in setting the timing for the emergence of the circadian clock oscillation during mammalian development.

In mammals, the circadian clock controls temporal changes of physiological functions such as sleep/wake cycles, body temperature, and energy metabolism throughout life (1–3). Although the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) functions as a center of circadian rhythms, most tissues and cells and cultured fibroblast cell lines contain an intrinsic circadian oscillator controlling cellular physiology in a temporal manner (4–7). The molecular oscillator comprises transcriptional/translational feedback loops (TTFLs) of circadian genes. Two essential transcription factors, CLOCK and BMAL1, heterodimerize and transactivate core circadian genes such as Period (Per1, 2, 3), Cryptochrome (Cry1, 2), and Rev-Erbα via E-box enhancer elements. PER and CRY proteins in turn repress CLOCK/BMAL1 activity and express these circadian genes cyclically (8, 9). REV-ERBα negatively regulates Bmal1 transcription via the RORE enhancer element, driving antiphasic expression patterns of Bmal1 (10, 11).

Although circadian clocks reside throughout the body after birth, mammalian zygotes, early embryos, and germline cells do not display circadian molecular rhythms (12–14), and the emergence of circadian rhythms occurs gradually during development (15–17). In addition, it has been elucidated that embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and early embryos do not display discernible circadian molecular oscillations, whereas circadian molecular oscillation is clearly observed in in vitro-differentiated ESCs (18, 19). Moreover, we have shown that circadian oscillations are abolished when differentiated cells are reprogrammed to regain pluripotency through reprogramming factor expression (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) (19), indicating that circadian clock development in mammalian cells is closely correlated with the cellular differentiation process.

Supporting these findings, perturbation of the cellular differentiation process of ESCs via DNA methyltransferase (DNMT, i.e., Dnmt1, 3a, 3b) deficiency during differentiation results in the abolishment of circadian clock development (20). As the misregulation of DNMTs affects global gene expression and induces dysdifferentiation through the impairment of epigenetic and transcriptional programs in various cell types (21–24), the failure of circadian clock development in these models indicates that adequately regulated cellular differentiation is indispensable for circadian clock development in mammalian cells (19, 20). Also, we recently found that Karyopherinα2 (Kpna2) overexpression disrupts cellular differentiation-coupled circadian clock development (20). KPNA2 was originally identified as an importin α subunit that is highly expressed in ESCs (25), and it plays a distinct role in maintaining pluripotency in ESCs by promoting the nuclear entry of OCT3/4 and preventing the nuclear entry of OCT6, which leads to differentiation (25, 26). Therefore, these findings provide further support that circadian clock development requires adequate cellular differentiation.

Cellular differentiation is a process to establish the cell lineage-specific gene-expression network regulated by global epigenetic and transcriptional programs (27, 28). Therefore, it is reasonable to predict that the emergence of circadian clock oscillation should be observed along with the cell lineage determination. However, previous studies showed that the intrinsic molecular oscillation appeared only around E13∼18 in mice fetal tissues such as heart and liver (29–32). Moreover, we previously demonstrated that the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during the in vitro differentiation of ESCs required ≥14 d in culture after the differentiation started (19, 20). Although pluripotent markers disappear by day 7 of differentiation in culture, circadian molecular oscillation had not yet emerged in these cells (19, 20). These findings suggest that additional mechanisms after the establishment of the cell lineage-specific gene-expression network are likely required for the activation of the mammalian circadian clock.

In this study, we investigated the mechanism that starts the circadian molecular oscillator cycle during the developmental process using mouse embryonic hearts and ESCs as models. Circadian gene reporter studies and temporal RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed a lack of core circadian TTFLs in E10–12 hearts as well as in the early differentiation stage (day 7) of ESCs. Next, using ESCs as a model system of differentiation-coupled circadian clock development, we showed that the gradual appearance of CLOCK protein during ESC differentiation correlated with the emergence of molecular oscillation. Mechanistically, we showed that the Dicer/Dgcr8-mediated posttranscriptional suppression of CLOCK protein contributes to the late development of the circadian clock oscillation. These findings indicate that the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock may play an important role for the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during mouse development.

Results

Cell-Autonomous Circadian Clock Has Not Developed in E9.5–10 Fetal Hearts.

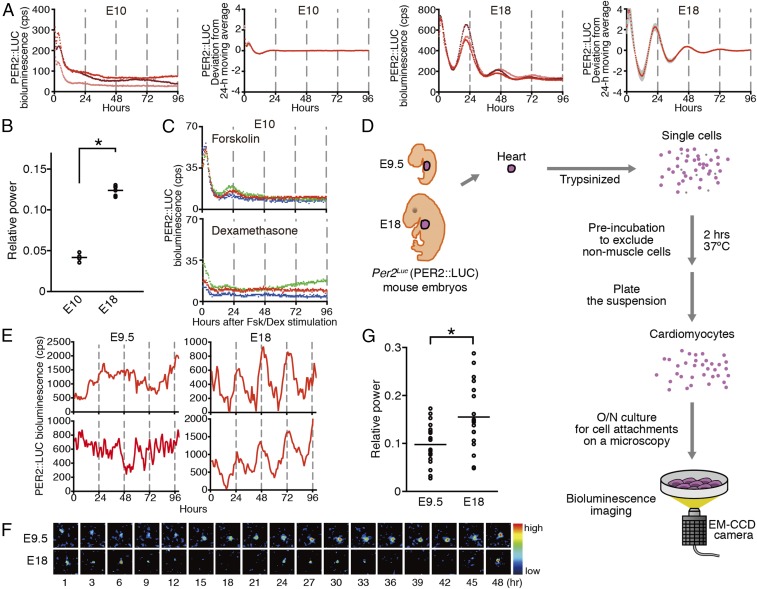

We first investigated circadian clock oscillation during mouse development after organogenesis. Hearts obtained at E10 did not display discernible circadian molecular oscillations, whereas E18 hearts exhibited apparent daily bioluminescence rhythms (Fig. 1 A and B). Synchronization stimulation using forskolin (Fsk) and dexamethasone (Dex) failed to induce detectable bioluminescence oscillation (Fig. 1C). A single-cell-level analysis using cardiomyocytes prepared from E9.5 and E18 fetal hearts indicated that cardiomyocytes derived from E9.5 embryos did not express apparent circadian Per2Luc bioluminescence rhythms, whereas circadian oscillation was observed in E18 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1 D–G). These results clearly reveal that the heart tissues of ∼E10 mouse fetuses do not have a functional cell-autonomous circadian clock.

Fig. 1.

Circadian PER2::LUC oscillation has not yet developed in E10 mouse hearts. (A) Bioluminescence traces from ex vivo culture of the embryonic hearts. Representative raw data (Left) and averaged detrended data by subtracting a 24-h moving average (Right) are shown for E10 and E18 hearts. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 4 or 6 biological replicates. The x axes indicate the time after culture in the supplemented DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium containing luciferin without Dex/Fsk stimulation. (B) FFT spectral power analysis of the bioluminescence from the mouse embryonic heart culture. The bars denote the mean (n = 4 or 6 biological replicates, two-tailed t test, *P < 0.01). (C) Bioluminescence traces from the E10 hearts stimulated by Fsk and Dex. The x axes indicate the time after stimulation. Data from three biological replicates are represented in different colors. (D) Scheme of the dispersed cell cultures of E9.5 and E18 Per2Luc embryos for single-cell bioluminescence imaging. (E and F) Representative single-cell bioluminescence traces (E) and image sequences (F) from the dispersed cardiomyocytes cultured without Dex/Fsk stimulation. The x axes indicate the time after recording. (G) FFT spectral power analysis of single-cell bioluminescence (n = 19 or 20 biological replicates, two-tailed t test, *P < 0.01).

Circadian Rhythm of Global Gene Expression Is Not Yet Developed in E10–12 Mouse Fetal Hearts in Vivo.

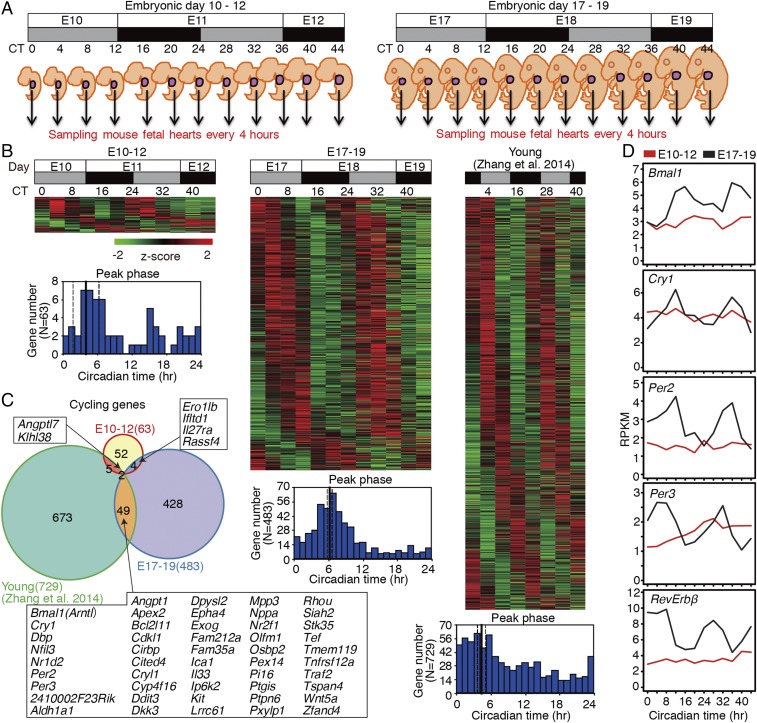

Although the cell-autonomous circadian clock did not cycle in E10 heart tissues, it might be possible that maternal circadian rhythms entrain or drive the fetal circadian clock in vivo. Therefore, we performed temporal RNA-seq analysis to investigate the circadian rhythmicity of global gene expression in E10–12 and E17–19 fetal hearts. Pregnant mice were housed under a 12-h:12-h light-dark (LD12:12) cycle (6:00 AM light onset) and then were subjected to constant darkness for 36 h before sampling. Sampling of fetal hearts was performed every 4 h for 44 h (two cycles) from circadian time 0 (CT0, i.e., 6:00 AM) at the E10 or E17 stage (Fig. 2A). We used E10–12 and E17–19 mouse hearts to perform polyA-selected RNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) (Dataset S1). Cardiomyocyte markers such as Mef2c, Nkx2.5, and Tbx5 were expressed in both E10–12 and E17–19 mouse fetal hearts, confirming the lineage commitment of the RNA-seq samples we used (Fig. S1). In young adult mice, ≈6% of genes in the hearts display circadian expression (33). Similarly, 4.0% (483 genes) of expressed genes in E17–19 hearts exhibited circadian expression rhythms (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, only 63 genes (0.5%) were rhythmically expressed in E10–12 hearts (Fig. 2B and Dataset S2). Only six cycling genes in E10–12 and E17–19 overlapped (Fig. 2C), and none of these was a known circadian-controlled gene. Conversely, several essential circadian genes and canonical clock-output genes such as Bmal1, Cry1, Per2, Per3, Nr1d2 (Rev-erbβ), and Dbp were detected as rhythmic in the hearts of E17–19 fetuses and young adult mice (Fig. 2 C and D and Datasets S2 and S3).

Fig. 2.

RNA-seq analysis of circadian gene expression in the mouse hearts. (A) Schematic representation of mouse heart sampling. The gray and black boxes indicate the subjective day and night, respectively, and the circadian time and embryonic day are indicated. (B) Heatmap view of cycling genes. Each gene is represented as a horizontal line ordered vertically by phase as determined by MetaCycle. The phase of each transcript rhythm is represented in the histogram plot. (C) Venn diagram of cycling genes in the mouse hearts. (D) Cyclic expression of circadian genes. RNA expression levels at E10–12 and E17–19 are indicated by red and black traces, respectively. The expression of Bmal1 (Arntl), Cry1, Per2, Per3, and Rev-Erbβ (Nr1d2) is circadian in E17–19 hearts (MetaCycle; P < 0.05).

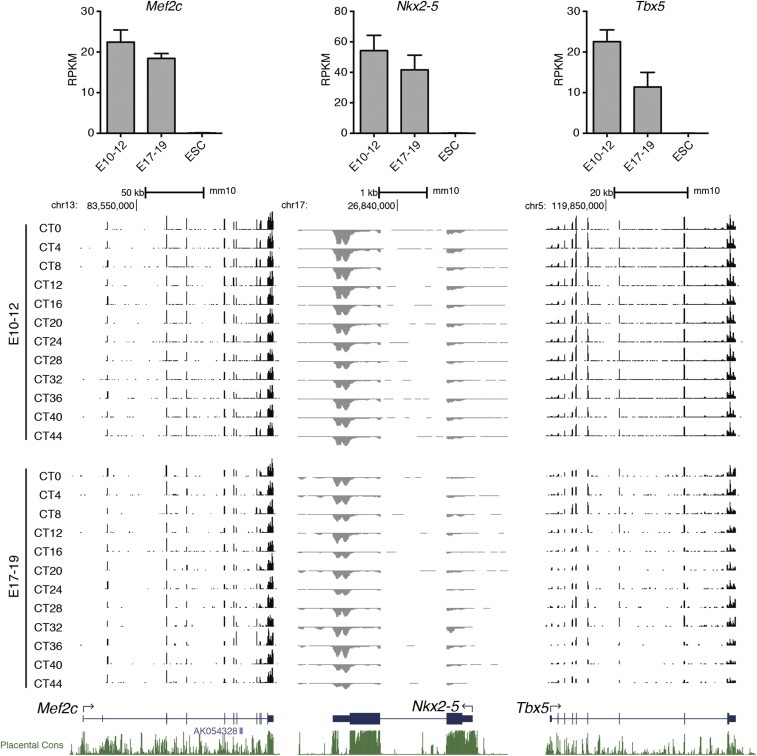

Fig. S1.

RNA expression of cardiomyocyte marker genes. (Upper) Average RPKM expression level of Mef2c (Left), Nkx2–5 (Middle), and Tbx5 (Right) in E10–12 and E17–19 hearts and ESCs. RPKM expression levels in ESCs are from ref. 20. Data are shown with the SD (n = 2–12 biological replicates). (Lower) UCSC genome browser views. Forward strand reads to the reference genome sequence are shown in black and reverse strand reads in gray as normalized average reads per 50 million total reads in 10-bp bins. The y axis scales are 0–100 for Mef2c and Tbx5 and −300 to 0 for Nkx2–5.

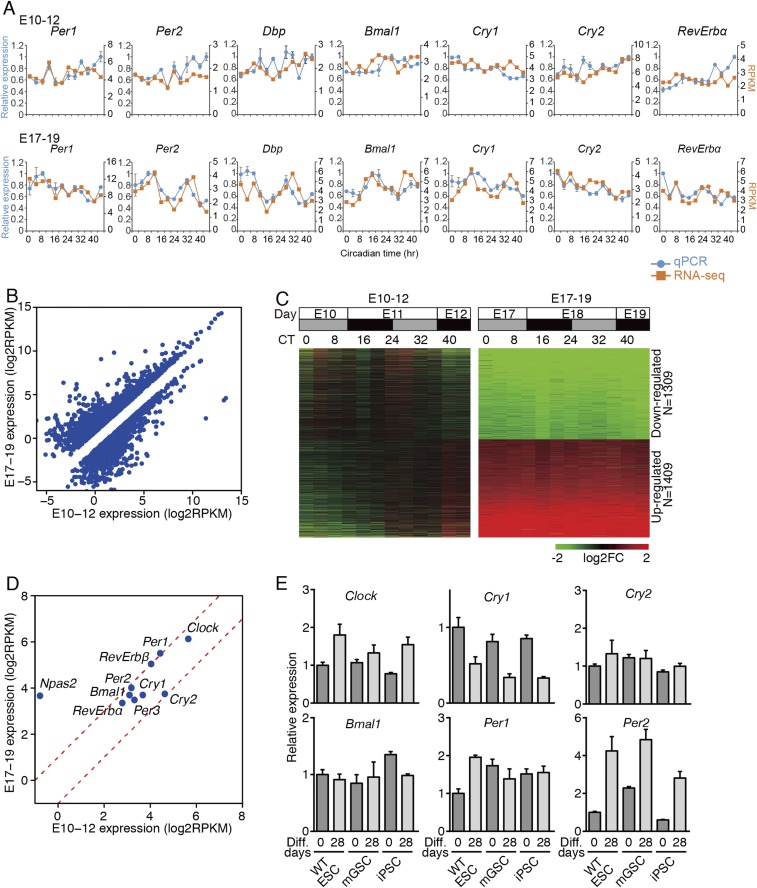

As the temporal profiles of circadian genes observed in the RNA-seq analysis were validated by qPCR analysis (Fig. S2A), evidence of circadian oscillation in core circadian genes was not detected in E10–12 hearts in vivo. Comparing the gene-expression levels between E10–12 and E17–19 fetal hearts, ≈2,700 genes exhibited altered expression: 1,309 were down-regulated, and 1,409 were up-regulated in E17–19 hearts (Fig. S2 B and C); however, the expression levels of core circadian genes (excluding Npas2) were not changed dramatically (Fig. S2D). These results indicate that core circadian TTFLs are not yet developed in E10–12 mouse fetal hearts in vivo despite the expression of essential circadian clock genes. This may also indicate that cell lineage determination such as cardiomyocyte differentiation is insufficient for the emergence of core circadian gene oscillations and that subsequent mechanism(s) are required for the completion of mammalian circadian clock development.

Fig. S2.

RNA expression profile. (A) Comparison of temporal RNA expression profiles using qPCR and exon RNA-seq analysis in E10–12 and E17–19 hearts. The exon RNA expression levels (orange) and relative RNA abundance measured by qPCR (blue) are indicated on the right and left y axes, respectively. The qPCR data shown are mean ± SD (n = 2 technical replicates). The expression of Per2, Dbp, Bmal1, and Cry1 in E17–19 hearts determined by RNA-seq and qPCR is circadian, and RevErbα expression in E17–19 hearts measured by qPCR is circadian (MetaCycle; P < 0.05). (B–D) Scatter plots (B) and heat map (C) of the down-regulated and up-regulated genes (EdgeR; P < 0.05, fold change >2) between E10–12 and E17–19 embryonic hearts and the scatter plot of the clock gene set (D) investigated by RNA-seq. Red dashed lines in D indicate twofold changes. All data were transformed to the log 2 base scale. (E) Gene-expression profiles of core clock genes at 0- or 28-d in vitro differentiation in indicated PSCs using qPCR. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates).

Emergence of Circadian Clock Oscillation Along with Posttranscriptionally Regulated CLOCK Expression During Differentiation Culture of ESCs.

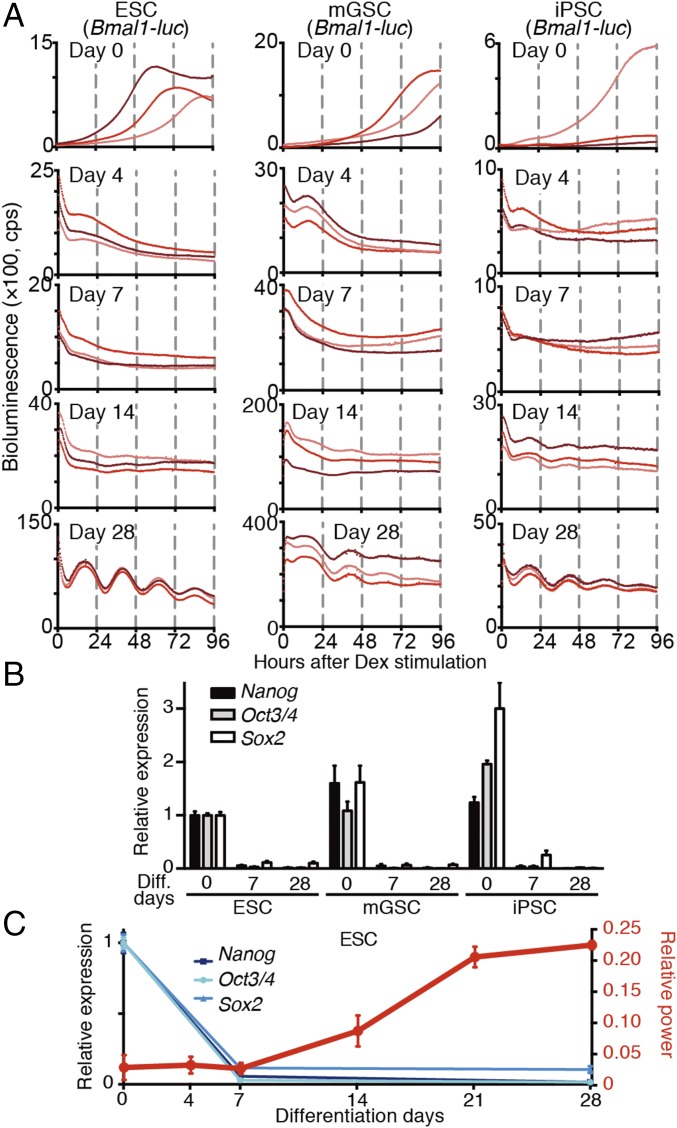

Next, we examined whether in vitro differentiation culture of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) could recapitulate and be a useful model system of late mammalian circadian clock development. To this end, not only ESCs but also other types of PSC lines such as induced PSCs (iPSCs) (34) and multipotent germline stem cells (mGSCs) (35) were tested for their ability to undergo differentiation-coupled circadian clock development in vitro. The PSC lines did not display circadian oscillation of Bmal1 promoter-driven luciferase (Bmal1-luc) bioluminescence (Fig. 3A). Moreover, although in vitro differentiation culture for 7 d resulted in the loss of pluripotent markers (Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2), none of the cell lines exhibited circadian clock oscillation at this differentiation state (Fig. 3 A and B). Conversely, molecular oscillation started to emerge after 14 d of differentiation, and all PSCs induced robust circadian clock oscillation after 28 d of differentiation culture (Fig. 3 A and C). These findings strongly suggest that a common principle controls differentiation-coupled circadian clock development in mammalian cells and that in vitro differentiation of PSCs recapitulates the late emergence of molecular clock oscillation. Therefore, we used ESCs as a model system to investigate the mechanism(s) regulating circadian clock development in mammals.

Fig. 3.

Differentiation-coupled circadian clock development PSCs emerged slowly after the complete loss of pluripotent markers. (A) Representative raw bioluminescence traces. All PSCs carrying Bmal1-luc reporters were differentiated in vitro for the indicated days. No PSCs exhibited any apparent circadian oscillation before day 14 of differentiation culture. Weak oscillation was detected at day 14, and apparent oscillation was observed at day 28 in all PSCs. (B) qPCR analysis of the pluripotent markers Nanog, Oct3/4 (also known as Pou5f1), and Sox2 in undifferentiated PSCs and 7- and 28-d in vitro-differentiated PSCs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). (C) Graphs of the relative expression levels of pluripotent markers of ESCs indicated in B (blue lines, mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates) and relative powers of circadian time of bioluminescence traces in ESCs during in vitro differentiation (red lines, mean ± SD, n = 4–6 biological replicates).

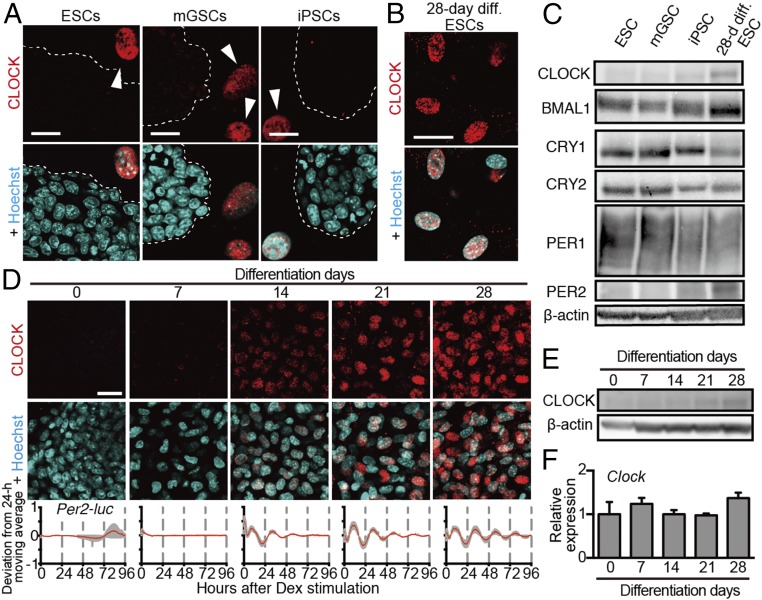

By surveying the expression of core clock proteins in PSCs, we found that CLOCK protein was absent in all PSCs (Fig. 4 A–C). Immunofluorescence analysis during in vitro differentiation culture revealed that the CLOCK was gradually detected beginning 14 d after differentiation, which correlates well with the timing of the emergence of molecular oscillation (Fig. 4 D and E). Interestingly, Clock mRNA was constitutively expressed throughout differentiation culture and in undifferentiated ESCs (Fig. 4F and Fig. S2E) (19, 20), indicating that posttranscriptional regulation controlled differentiation-coupled CLOCK protein expression.

Fig. 4.

Absence of CLOCK in PSCs and its gradual appearance during the in vitro differentiation of ESCs concomitant with the emergence of circadian oscillation. (A and B) Representative immunostaining of CLOCK protein in ESCs, mGSCs, iPSCs, (A) and 28-d differentiated (28-d diff) ESCs (B). Immunostaining (red) and Hoechst nuclear staining (blue) are shown. Feeder MEFs are indicated by arrowheads in A. PSCs are surrounded by dotted lines in A. (C) Western blots of core circadian proteins in ESC, mGSC, iPSC, and 28-d diff ESCs (n = 1 or 2 biological replicates). (D) Temporal expression of CLOCK protein during differentiation. (Top and Middle) Representative immunostaining (n = 2–4 biological replicates) is shown as described in A. (Bottom) Averaged bioluminescence traces (SEM, n = 3 or 6 biological replicates) were detrended by subtracting the a 24-h moving average of in vitro-differentiated ESCs carrying mPer2 promoter-driven luciferase reporters at the indicated times. (E and F) Representative Western blot analysis of CLOCK protein (n = 2 biological replicates) (E) and qPCR analysis of Clock mRNA (F) for in vitro-differentiated ESCs for the indicated days. Data are shown with the SD (n = 3 biological replicates).

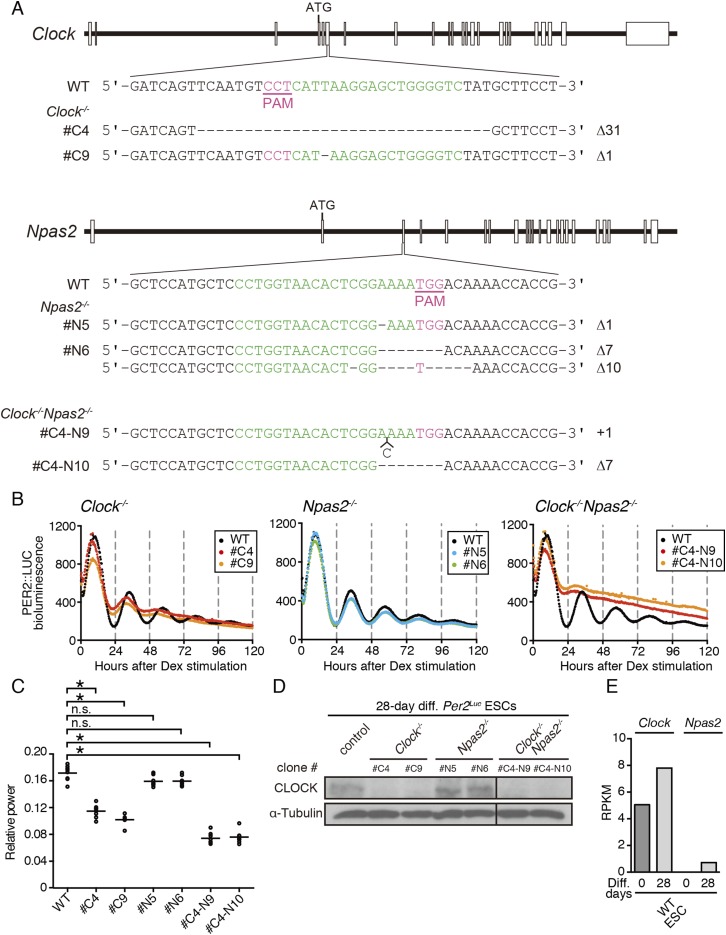

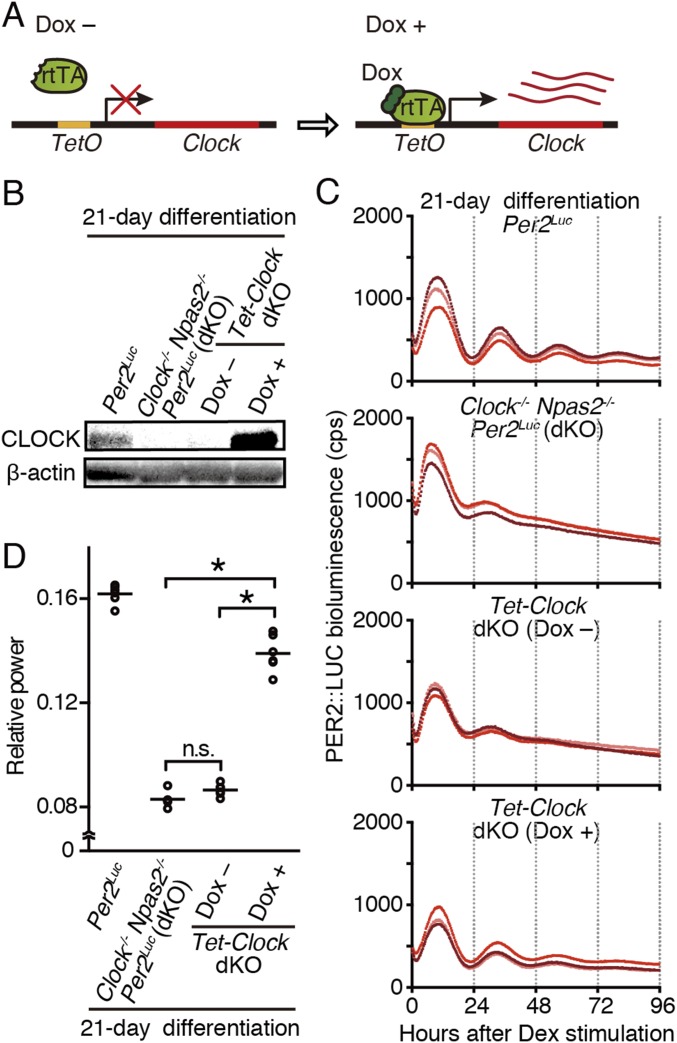

Next, to elucidate the importance of CLOCK expression for the emergence of circadian oscillation, we generated Clock- and/or Npas2-deficient Per2Luc ESC lines (Fig. S3 A–D). In an in vitro differentiation assay, Clock played a dominant role in the emergence of circadian clock oscillation (Fig. S3 B and C), which was compatible with previous studies demonstrating the importance of Clock for circadian rhythms in most peripheral tissues (36). Npas2 can compensate for Clock function in neuronal tissues such as the SCN (32, 36, 37). Npas2 was almost undetectable in undifferentiated ESCs, and although a low level of Npas2 expression was detectable in the 28-d differentiated cells (Fig. S3E), the disruption of Npas2 showed only a subtle effect on the circadian oscillation in the differentiated cells (Fig. S3 B–E). Moreover, doxycycline-dependent Clock expression rescued circadian clock oscillation in Clock/Npas2 doubly deficient (dKO) ESCs after differentiation culture (Fig. S4). These results support the importance of CLOCK protein expression for circadian clock development during ESCs differentiation.

Fig. S3.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of Clock and Npas2. (A) Schematic representations of Clock and Npas2 target regions and the DNA sequences of WT and knockout ESCs. The boxes represent exons, and the first start codon (ATG) is indicated. The target DNA sequences for guide RNAs and proto-spacer-adjacent motif (PAM) are indicated in green and red, respectively. The number of inserted (+) or deleted (Δ) nucleotides is indicated at the right of each clone. Clock- or Npas2-deficient ESCs were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing from Per2Luc ESCs, and Clock and Npas2 dKO ESCs were from a #C4 Clock-knockout clone. The #N6 Npas2 knockout carries different deletion in the allele, as indicated; the others have the same deletion or insertion in both alleles. (B) Representative bioluminescence traces of WT or Clock- and/or Npas2-deficient ESCs after 28-d differentiation in vitro. (C) FFT spectral power analysis of bioluminescence data in B. Bars indicate the mean (n = 6 biological replicates, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons tests; n.s., not significant, *P < 0.01). The FFT relative power of Npas2−/− was similar to that of WT Per2Luc. (D) Representative Western blot of CLOCK in Clock- and/or Npas2-knockout ESCs (n = 2 technical replicates). The cells were differentiated for 28 d in vitro. (E) mRNA expression of Clock and Npas2 in undifferentiated ESCs and in WT ESCs differentiated for 28 d quantified from our previously published data (n = 1) (20).

Fig. S4.

Expression of CLOCK is essential for cellular differentiation-coupled circadian clock development. (A) Schematic representation of doxycycline (Dox)-dependent Clock rescue ESCs. Dox-inducible Clock ESCs (referred to as “Tet-Clock dKO”) were established using transposon-based insertion of CAG-rtTA and Tet-Clock in Clock/Npas2 dKO Per2Luc ESC lines. (B) Representative Western blot analysis of CLOCK in 21-d differentiated ESCs (n = 2 technical replicates). CLOCK is not detectable in dKO or Tet-Clock dKO ESCs in the absence of Dox (Dox−). By contrast, CLOCK is expressed in WT Per2Luc cells, and strong expression was observed in Tet-Clock dKO cells in the presence of Dox (Dox+). (C) Representative Per2Luc-driven bioluminescence in 21-d differentiated ESCs. Circadian bioluminescence is severely attenuated in dKO and Tet-Clock dKO (Dox−) ESCs and is rescued by CLOCK overexpression in Tet-Clock dKO (Dox+) ESCs to a level similar to that in Per2Luc ESCs. (D) FFT spectral power analysis of bioluminescence data from 21-d in vitro-differentiated Per2Luc, dKO, Tet-Clock dKO (Dox−), and Tet-Clock dKO (Dox+) ESCs. Bars indicate the mean (n = 6 biological replicates, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparison tests, *P < 0.01). The FFT relative power in Tet-Clock dKO (Dox+) cells is increased to a level similar to that in Per2Luc cells. n.s., not significant.

Acceleration of Circadian Clock Development by CLOCK Overexpression During in Vitro Differentiation.

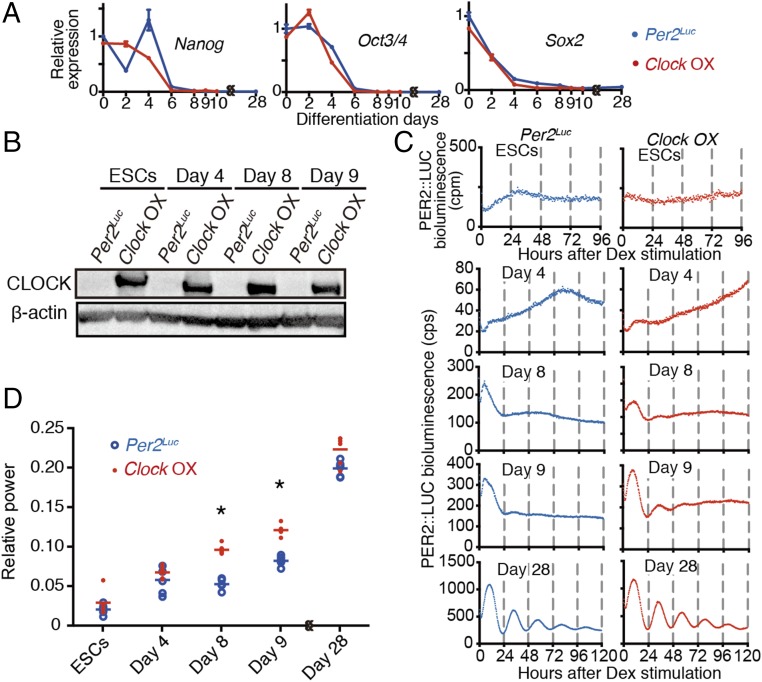

Next, we determined whether CLOCK protein expression can evoke the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during in vitro differentiation. Doxycycline-inducible Per2Luc ESCs overexpressing Clock (Clock OX) were used for in vitro differentiation assays. Expression of pluripotent markers (Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2) rapidly decreased to almost undetectable levels at day 6 of in vitro differentiation culture in both Per2Luc and Clock OX ESCs (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Clock overexpression did not influence the cellular differentiation process. We then compared the development speed of circadian molecular oscillators during in vitro differentiation between the cells with or without Clock overexpression. Since Clock OX ESCs showed leaking Clock expression without doxycycline, WT Per2Luc ESCs were used as a control. Although a Western blot confirmed that the CLOCK protein was expressed throughout the differentiation culture in Clock OX cells (Fig. 5B), CLOCK overexpression failed to evoke Per2Luc-driven circadian bioluminescence in undifferentiated ESCs (Fig. 5C). An in vitro differentiation assay revealed that the Per2Luc-driven circadian bioluminescence rhythm had appeared earlier in Clock OX cells than in Per2Luc cells (Fig. 5C), and the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) relative power of Clock OX cells at day 8 and day 9 during differentiation was significantly higher than that of Per2Luc cells (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that the early expression of CLOCK protein by Clock overexpression during the differentiation of ESCs accelerates the circadian clock development. Moreover, the lack of a significant increase in the FFT relative power in ESCs and in Clock OX cells at day 4 suggested that the CLOCK expression was not solely sufficient for the induction of circadian clock cycling.

Fig. 5.

CLOCK expression was insufficient for the circadian clock cycling in the undifferentiated ESCs. (A) Temporal expression profiles of Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2 genes during in vitro differentiation culture of Per2Luc (blue traces) and Clock-overexpressed Per2Luc (Clock OX, red traces) ESCs. Data are shown with SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). (B) Expression profile of CLOCK protein in ESCs and at day 4, 8, and 9 after in vitro differentiation of Per2Luc and Clock OX ESCs (n = 1). (C and D) Representative bioluminescence traces (C) and FFT spectral power analysis (D) of ESCs and 4-, 8-, 9-, and 28-d differentiated ESCs. Bars indicate the mean (n = 6 biological replicates, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons tests, *P < 0.01).

CLOCK Expression in E10 Mouse Fetal Hearts Is also Posttranscriptionally Suppressed.

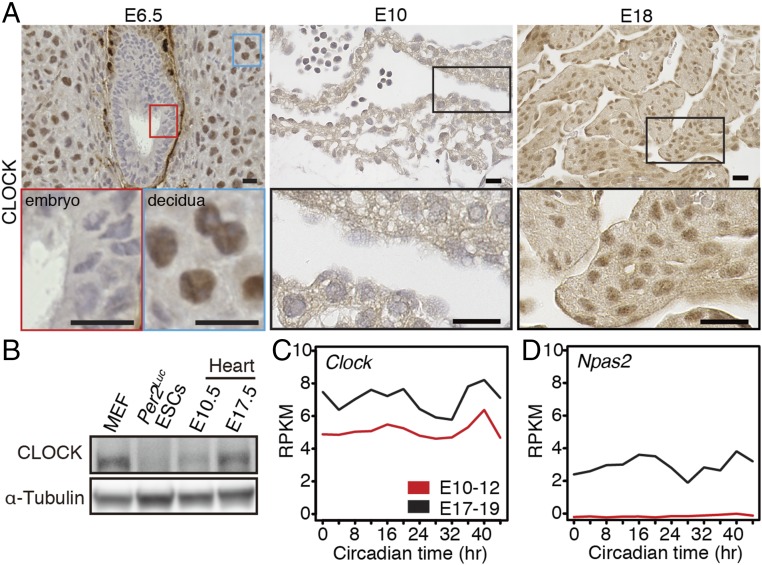

Using ESCs, we identified the contribution of posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK expression to the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during the differentiation culture. To examine whether this mechanism is at play during mammalian circadian clock development in vivo, we investigated CLOCK expression in mouse embryos and fetuses. Immunohistochemistry revealed that E6.5 embryos and E10 fetal hearts did not express CLOCK, whereas apparent signals against CLOCK were observed in the nuclei of E17.5 fetal hearts and maternal uterus tissue (decidua) surrounding E6.5 embryos (Fig. 6A). Western blotting also confirmed that CLOCK expression was hardly detectable in E10.5 fetal heart, whereas clear expression of CLOCK was observed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as well as E17.5 fetal heart (Fig. 6B). RNA-seq data using E10–12 and E17–19 fetal hearts revealed that Clock mRNA was constitutively expressed at both developmental stages (Fig. 6C), indicating that the suppression of CLOCK in E10 fetal hearts was most likely due to posttranscriptional regulation, as observed in ESCs. Because Clock and Npas2 are indispensable to generate circadian rhythm (36, 37), and Npas2 mRNA was not expressed in E10–12 fetal hearts (Fig. 6D), the lack of CLOCK expression by the posttranscriptional inhibition is at least one of the reasons for the absence of cell-autonomous circadian clock oscillation in E10 hearts.

Fig. 6.

The absence of CLOCK expression in early embryos. (A) Representative immunohistochemistry of CLOCK in embryos, decidua, and embryonic hearts on the indicated days (n = 3 biological replicates). (Scale bars, 20 µm.) (B) Representative Western blot analysis of CLOCK proteins in MEFs, Per2Luc ESCs, and E10.5 and E17.5 hearts (n = 2 biological replicates). (C and D) mRNA expression levels of Clock (C) and Npas2 (D) in embryonic hearts using RNA-seq data.

Dicer/Dgcr8-Mediated Posttranscriptional Mechanism Suppresses Clock Translation.

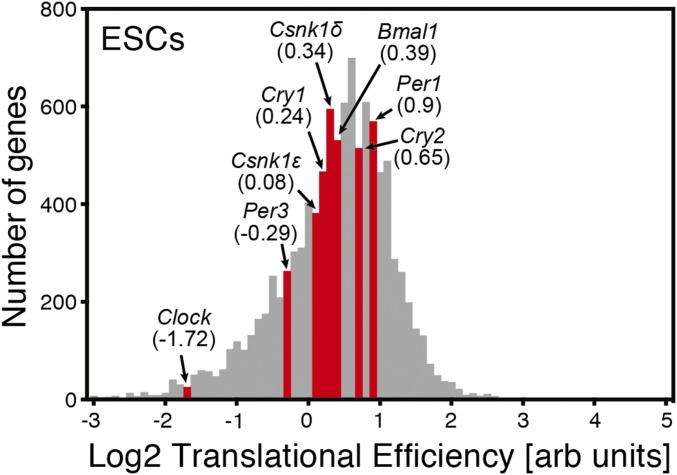

As E10 mouse fetal hearts and premature differentiated ESCs, both lacking detectable cell-autonomous circadian oscillation, did not express CLOCK, we further investigated the mechanism of the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock. Using the open database for genome-wide translational efficiency in ESCs based on ribosome profiling reported by Ingolia et al. (38), we found that the translational efficiency of Clock mRNA in undifferentiated ESCs is extremely low compared with that of other circadian genes (Fig. S5). This supports the hypothesis that the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock inhibits its translation in ESCs.

Fig. S5.

Genome-wide translational efficiency from Ingolia et al. (38). A histogram of log-scaled translational efficiencies in ESCs. Translational efficiency for each gene was computed from the ratio of ribosome footprint density to mRNA abundance. Values in parentheses represent the translational efficiency of the indicated genes. The translational efficiency of Clock is extremely low compared with the other clock genes in undifferentiated ESCs.

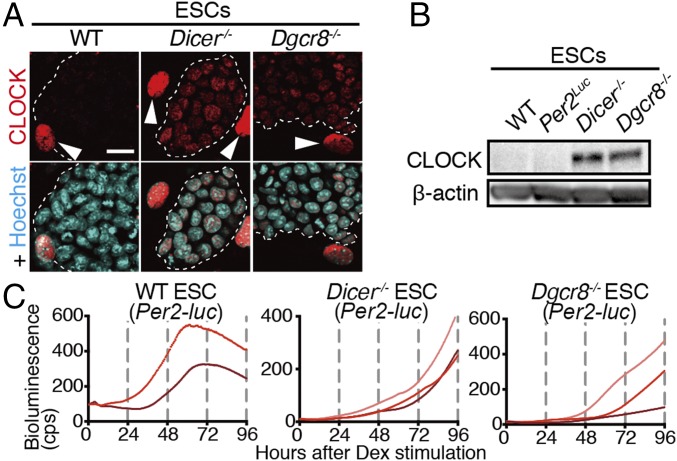

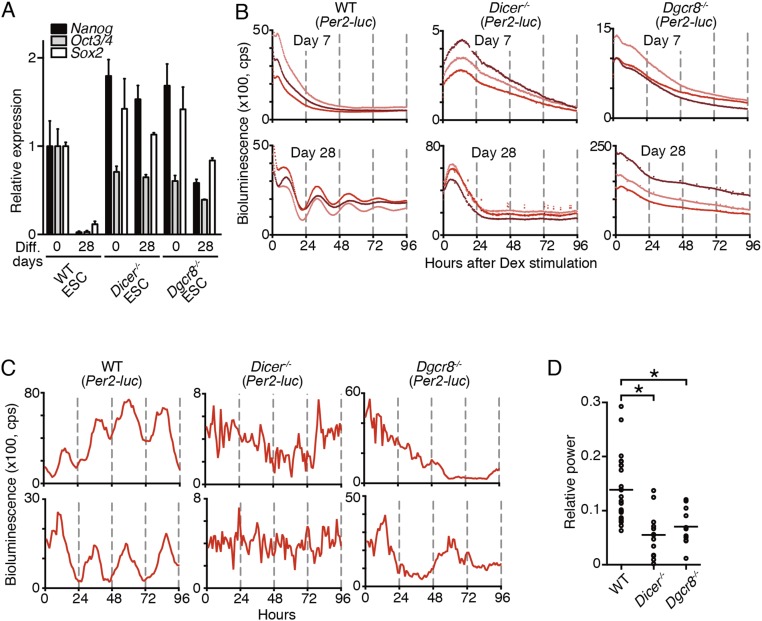

Because DICER- and DGCR8-mediated biosynthesis of miRNAs plays essential roles in the inhibition of the translation of various genes (39, 40), we next examined the effects of genetic ablation of Dicer and Dgcr8 on CLOCK expression in ESCs. Both immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of CLOCK proteins in Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs (Fig. 7 A and B). These results revealed that the DICER/DGCR8-dependent posttranscriptional mechanism regulated CLOCK expression in ESCs. To measure circadian clock oscillation in the Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs, mouse Per2 promoter-driven luciferase reporters were introduced. We observed that the circadian clock did not oscillate in Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs despite CLOCK expression in these cells (Fig. 7C). Since the loss of Dicer or Dgcr8 in ESCs causes differentiation defects in vivo and in vitro (41, 42), and ESC markers such as Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2 were still expressed after 28-d in vitro differentiation of Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− cells (Fig. S6A), the lack of circadian oscillation in these cells is due to the failure of differentiation (Fig. S6 B–D). These results reveal that the adequate cellular differentiation process is a prerequisite for the emergence of circadian oscillation before CLOCK expression.

Fig. 7.

Absence of circadian clock oscillation in undifferentiated Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs. (A) Representative immunostaining of CLOCK proteins in undifferentiated WT, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs as shown in Fig. 4A (n = 2–5 biological replicates). (B) Representative Western blots of core CLOCK proteins in WT, Per2Luc, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs (n = 2 biological replicates). (C) Representative raw bioluminescence traces in undifferentiated WT, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs carrying mPer2 promoter-driven luciferase reporters.

Fig. S6.

Per2-luc–driven circadian oscillation failed to appear not only in the undifferentiated Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs but also after 28-d differentiation culture. (A) qPCR analysis of pluripotent markers, Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2 in undifferentiated ESCs (0) or in vitro 28-d differentiated ESCs. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). (B) Representative bioluminescence traces after in vitro 7- and 28-d differentiation of ESCs carrying Per2-luc reporters. (C and D) Representative single-cell bioluminescence traces (C) and FFT spectral power analysis of bioluminescence (D) of ESCs carrying Per2-luc reporters after 28-d differentiation in vitro. The bioluminescence from the cells was monitored after medium change without Dex/Fsk stimulation, and the time after monitoring is indicated in C. In D, each circle represents a single cell, and bars indicate the mean (n = 11–24 biological replicates, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons tests, *P < 0.01).

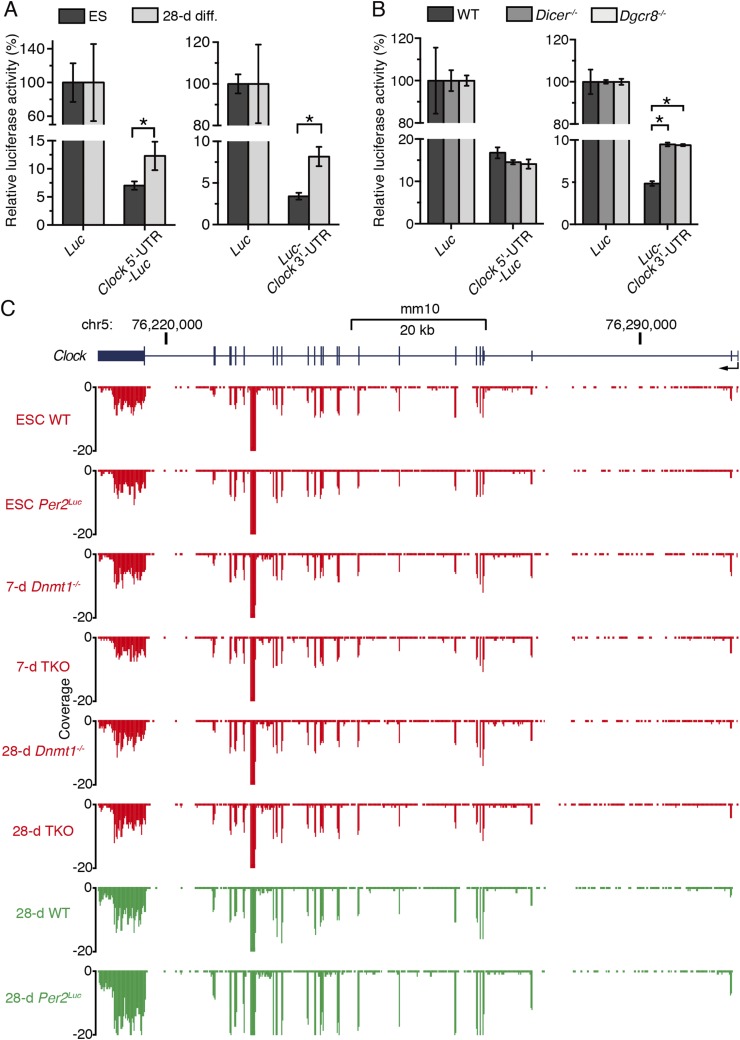

To validate that the Clock UTR contains cis-regulatory elements of posttranscriptional suppression, we compared expression levels of Clock 5′ or 3′ UTR-fused luciferase in undifferentiated ESCs with 28-d in vitro-differentiated ESCs. Both Clock 5′ and 3′ UTRs significantly reduced luciferase activities in ESCs compared with 28-d in vitro-differentiated ESCs (Fig. S7A). The luciferase activities of Clock 3′ UTR-fused luciferase reporter were significantly increased in both Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs compared with WT ESCs, although the Clock 5′ UTR-fused luciferase reporter showed a subtle effect in both Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs (Fig. S7B). These results suggest that the Clock 3′ UTR possesses the cis-elements for Dicer/Dgcr8-mediated posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK expression and works more efficiently than the Clock 5′ UTR.

Fig. S7.

Analysis of posttranscriptional CLOCK suppression. (A) Relative luciferase activities of Clock 5′ or 3′ UTR-fused luciferase reporters in ESCs and 28-d differentiated ESCs (28-d diff). Luciferase reporter expression levels were normalized by dividing firefly luciferase activity by that of Renilla luciferase, and the mean of the ratio of each Luc was set to 100% in ESCs and in 28-d differentiated ESCs to normalize the cell type-dependent differences in transfection and expression efficiency of the luciferase reporter. Data are shown as mean with SD (n = 2 or 3 biological replicates, one-tailed t test, *P < 0.05). After 28 d of differentiation culture ESCs are tightly attached to each other and form a film-like cell sheet, which results in the extremely low efficiency of transfection. Thus, the cells differentiated for 27 d were trypsinized and passaged to newly prepared dishes, and then reporter vectors were transfected. Although about 50% of differentiated cells were not viable after the passage, luciferase activities fused with Clock 5′ and 3′ UTR were significantly up-regulated after differentiation culture. (B) Luciferase reporter expression levels in the indicated ESCs. Luciferase activities were normalized as described in A. The mean of the ratio of each Luc was set to 100% in WT, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs. Data are mean with SD (n = 3 biological replicates, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons tests, *P < 0.01). (C) UCSC genome browser views of RNA-seq data at Clock in the indicated cells (red, nonrhythmic cells; green, rhythmic cells). The reads shown are normalized average reads per 50 million total reads in 10-bp bins from ref. 20.

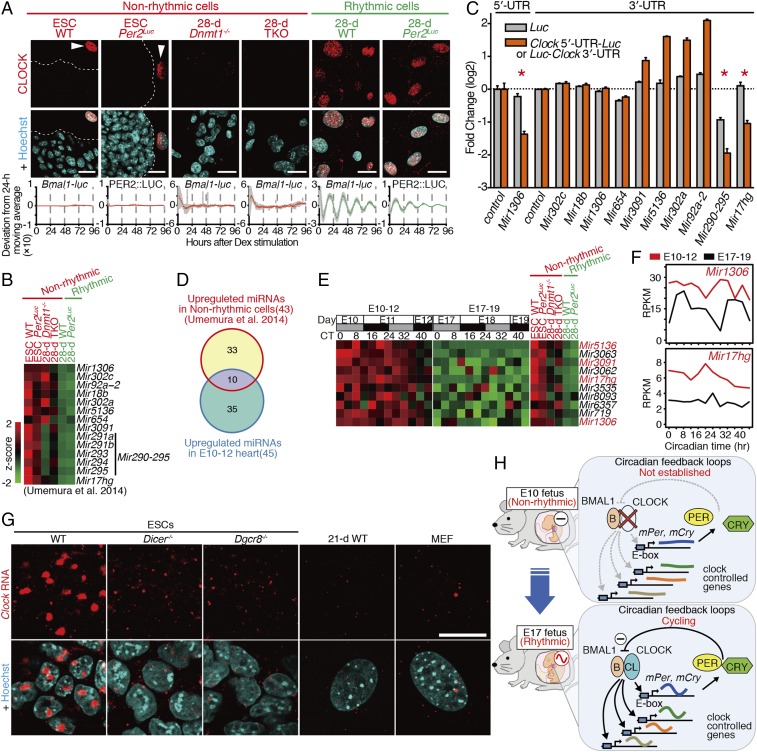

Next, we extracted candidate miRNAs among the predicted miRNAs targeting the UTRs of Clock mRNA (43). To extract the candidate miRNAs, we used recently obtained RNA-seq data from WT and Dnmt (Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b)-deficient ESC lines (20). In Dnmt1−/− and Dnmt1−/− Dnmt3a−/− Dnmt3b−/− triple-knockout (TKO) ESCs, neither CLOCK expression nor circadian clock oscillation was detected after differentiation culture for 28 d (Fig. 8A). We previously showed that ESC markers (Nanog, Oct3/4, and Sox2) were still expressed in the Dnmt1−/− and TKO cells after 28-d differentiation culture (20), suggesting that the lack of CLOCK and circadian rhythm in these cells may also be due to the failure of adequate differentiation. As Clock mRNA is constitutively expressed in these Dnmt-deficient cells throughout differentiation culture (Fig. S7C) (20), CLOCK expression is expected to be also inhibited via a posttranscriptional mechanism in these cells as observed in the undifferentiated WT ESCs and E10 mouse hearts. Using the RNA-seq data, we extracted eight candidate miRNAs and two miRNA clusters that were commonly up-regulated in ESCs and the Dnmt-deficient cells (designated “nonrhythmic cells”) lacking CLOCK expression and circadian clock oscillation (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

miRNA-mediated posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK protein expression. (A) Representative immunostaining of CLOCK in rhythmic and nonrhythmic cells as indicated. The averaged bioluminescence-detrended traces in the indicated cells carrying Bmal1-luc reporter (WT, Dnmt1−/−, and TKO) or Per2Luc are shown. Data are shown with the SEM (n = 2–4 biological replicates). (B) Heatmap view of the up-regulated miRNA candidate genes targeting Clock UTRs in nonrhythmic cells. (C) Luciferase reporter assay to validate the miRNA targets. The relative activities of luciferase reporters with Clock 5′ UTR (Clock 5′-UTR-Luc), Clock 3′ UTR (Luc-Clock 3′-UTR), or no UTRs (Luc) were assayed 24 h after cotransfection with the indicated miRNAs or vector plasmid (control). Data are shown with the SEM (n = 3 biological replicates, two-tailed t test, *P < 0.01) (D) Venn diagram of up-regulated miRNAs in E10–12 hearts and nonrhythmic cells. (E) Heatmap view of commonly up-regulated miRNAs in E10–12 hearts and nonrhythmic cells. (F) RNA expression levels of Mir1306 and Mir17hg from RNA-seq data. (G) Representative image of single-molecule RNA FISH of Clock in the indicated ESCs, 21-d differentiated WT ESCs (21-d WT), and MEFs (n = 2 biological replicates). (Scale bar, 20 µm.) (H) Model of circadian clock development during gestation. At E10, circadian feedback loops are not yet established in fetal tissues due to posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK expression. In the E17 fetus, the CLOCK protein is expressed, the circadian feedback loops are cycling, and the clock-controlled genes are rhythmically expressed and entrained by maternal time cues.

Luciferase reporter-based posttranscriptional repression assays using the Clock 5′ or 3′ UTR-fused luciferase mRNA expression constructs revealed that Mir1306, Mir290-295, and Mir17hg statistically significantly inhibited the translational efficiency (Fig. 8C). In mouse embryos, 45 miRNAs were up-regulated in E10–12 hearts relative to their expression in E17–19 hearts (Fig. 8D). Among them, 10 miRNAs were also up-regulated in nonrhythmic cells including ESCs (Fig. 8E). Strikingly, two functionally identified miRNA genes, Mir1306 and Mir17hg, were highly and constitutively expressed in E10–12 hearts (Fig. 8F). These findings suggest that common mechanisms may be involved in the posttranscriptional inhibition of Clock translation in both ESCs and E10–12 hearts and that the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock may contribute to the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during the later stages of development in mammals.

Although our data suggested that the miRNA genes inhibited the Clock 5′ and 3′ UTR-fused luciferase reporter activities, their inhibitory effects were partial and limited. Therefore, we considered the possibility that additional mechanisms contribute to posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK expression. By using FISH, we found Dicer/Dgcr8-dependent nuclear retention of Clock transcripts in undifferentiated ESCs (Fig. 8G and Dataset S4). Interestingly, the nuclear retention of Clock transcripts was dramatically reduced in Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs as well as in the 21-d differentiated ESCs and MEFs that expressed CLOCK protein (Fig. 8G). RNA-seq data showed that more reads were mapped to exons than to introns in both ESCs and 28-d differentiated cells, suggesting that the nuclear-accumulated Clock transcripts are mainly in their spliced form (Fig. S7C). These results suggest that the nuclear retention of Clock transcripts may also contribute to the Dicer/Dgcr8-dependent inhibition of CLOCK protein expression in ESCs in addition to the identified miRNA genes described above.

Taken together, our findings indicate that cell-autonomous circadian rhythms in E10 mouse fetus hearts do not emerge in vivo due to lack of circadian TTFLs, whereas E17 hearts, with the expression of CLOCK protein, exhibit circadian rhythms with their cycling cell-autonomous circadian oscillator (Fig. 8H). We revealed that Dicer/Dgcr8-mediated posttranscriptional regulation of CLOCK contributes to the mechanisms for the initiation of the molecular clock during in vitro cellular differentiation and that posttranscriptional regulation may also be involved in the establishment of circadian TTFLs during ontogenesis.

Discussion

Lack of Cell-Autonomous Circadian Rhythms Around E10 in the Mouse Fetal Heart.

Circadian clocks regulate the daily fluctuations of essential biological processes from the molecular to organismal levels to predict and adapt to the cyclic environment of our rotating planet (44). Cell-autonomous circadian clocks exist in both the SCN and peripheral cells throughout the body (4–7), suggesting that circadian clocks may function as an interface connecting cyclic environmental changes and cellular physiology. Therefore, the emergence of functional circadian rhythms in peripheral cells and SCN neurons is important for mammalian fetal physiology.

We demonstrated that cell-autonomous circadian clock oscillation was undetectable in cardiomyocytes prepared from E9.5 mouse fetal hearts. Moreover, temporal RNA-seq analysis revealed that fewer genes exhibited circadian expression rhythms in E10–12 fetal hearts than in E17–19 fetal hearts in vivo. In mammalian peripheral tissues, both their cell-autonomous oscillator and the temporal cues from the central pacemaker SCN entrain gene expression and functions of peripheral tissues in a circadian manner (45). Similar to peripheral tissues, it is believed that the maternal circadian rhythms entrain the fetus throughout development (15, 16, 29, 46). Supporting the maternal entrainment theory, our RNA-seq data for E17–19 fetal hearts uncovered synchronized rhythms with similar peak phases (Fig. 2B). This suggests that global gene expression is strongly entrained by maternal cues in E17–19 embryos. However, the number of fluctuating genes was extraordinarily fewer and the phases of their rhythms were more diverged in E10–12 hearts than in E17–19 hearts (Fig. 2B), indicating the possibility that an undeveloped entrainment system responded to maternal circadian cues in E10–12 fetuses. Currently, there is no evidence as to whether the maternal melatonin rhythm can entrain E10–12 mouse fetuses, because the C57BL/6J mouse strain used here lacks melatonin synthesis; this possibility warrants future studies.

Posttranscriptional Regulation of Clock as a Common Mechanism Controlling the Emergence of the Mammalian Circadian Oscillation in ESCs in Vitro and in Developing Hearts in Vivo.

Here we demonstrated that the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock plays a potential role in the emergence of circadian clock oscillation in mammalian development. As CLOCK protein is switched on in Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs, DICER/DGCR8 is essential for the posttranscriptional suppression of CLOCK. Furthermore, we identified Mir1306 and two miRNA clusters (Mir290–295 and Mir17hg) exerting partial inhibitory effects on translational efficiency of Clock by targeting the 5′ or 3′ UTR of Clock mRNA, which is supported by recent transcriptome analysis in which Mir294 is proposed as a potential regulator of Clock (42). Intriguingly, two of these miRNA genes (Mir1306 and Mir17hg) were also up-regulated in E10–12 mouse fetal hearts in which CLOCK expression was posttranscriptionally inhibited. Furthermore, although the distinct mechanism is not understood, we found that Dicer/Dgcr8-dependent nuclear accumulation of Clock transcripts in undifferentiated ESCs, which is also a possible mechanism controlling the CLOCK expression. It has been reported that cationic amino acid transporter 2 (CAT2) protein expression was inhibited through RNA nuclear retention (47), indicating that Clock mRNA retention in the nucleus is a rational reason for posttranscriptional inhibition of CLOCK protein expression. Our study suggests that a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism contributes to the expression of CLOCK and the emergence of circadian clock oscillation in both mouse fetal tissues and ESCs.

Recently, it was reported that Npas2, a paralog of Clock, could compensate for Clock function in both the SCN and other peripheral cells (48). However, peripheral cells obtained from Clock-deficient mice displayed weaker and more unstable circadian molecular oscillation (48), in agreement with previous findings illustrating the importance of Clock for circadian rhythms in most peripheral tissues (36). Supporting these results, we demonstrated that CLOCK played a dominant role in the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during in vitro differentiation culture of ESCs. Also, no Npas2 expression was detected in either ESCs or E10–12 fetal hearts (Fig. 6D and Fig. S3E), indicating that the repression of Npas2 expression in undifferentiated cells or in early developmental stages may have additionally contributed to the diminished circadian clock oscillation in these cells.

Meanwhile, a previous report revealed that the cold-induced RNA-binding protein rhythmically regulated CLOCK expression posttranscriptionally in MEFs, which modulate the robustness of circadian clock oscillation (49). Also, it has been reported that Drosophila Clock (Clk) is regulated posttranscriptionally, which inhibits the ectopic expression of Clk and CLK-transcriptional targets (50). Although we could not eliminate the possibility of a Drosophila-like mechanism here, these findings suggest that the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock may play important roles in establishing and tuning the circadian clock in various species.

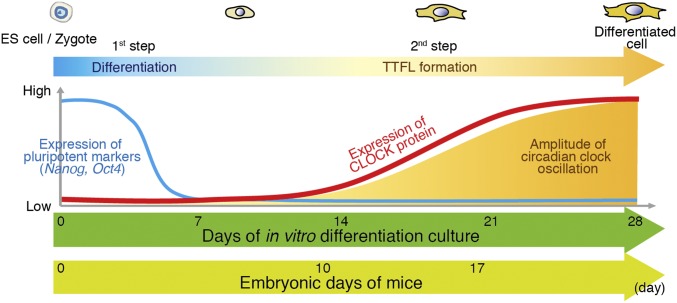

Taken together, our findings demonstrated that E10 mouse fetal hearts do not display apparent cell-autonomous circadian clock oscillation, in which the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock inhibits CLOCK expression. We showed that similar mechanisms also exist in PSCs such as ESCs. Although the expression of CLOCK on its own is not sufficient for circadian clock oscillation in undifferentiated ESCs, the regulation of CLOCK expression may affect the timing of the emergence of circadian clock oscillation during cellular differentiation and developmental processes in mammals. Therefore, our results suggest that the development of the mammalian circadian clock requires two steps. The first is an epigenetic- and transcriptional program-mediated cellular differentiation process (the cell-lineage determination process), and the second is the establishment of the TTFLs of the mammalian circadian clock in which the posttranscriptional regulation of Clock functions as a rate-modulating mechanism (Fig. S8). These sequential mechanisms may explain, at least in part, the late emergence of mammalian circadian clock oscillation in the developmental process.

Fig. S8.

Schematic representation of differentiation coupled emergence of circadian clock in vitro and in vivo. For in vitro differentiation of ESCs, pluripotent markers such as Nanog and Oct3/4 are highly expressed in ESCs and are repressed before 7-d in vitro differentiation. CLOCK protein is gradually expressed after 14-d differentiation, along with the increasing amplitude of circadian molecular oscillations. Likewise, mouse zygotes and early embryos do not show circadian molecular oscillation (12–14). The highly expressed pluripotent markers are down-regulated, and then CLOCK protein is expressed after E10. The robust circadian clock oscillates at E17.

Materials and Methods

Pregnant C57BL/6J females raised under LD12:12 conditions (lights on at 6:00 AM, lights off at 6:00 PM) were purchased from Japan CLEA, Inc. Animals were maintained under LD12:12 conditions and were transferred to a constant dark condition for 36 h before sampling. The morning after the vaginal plug was found was designated day E0.5. Embryonic heart samples were collected every 4 h for 44 h from CT0 (6:00 AM). The mothers were killed by cervical dislocation in the dark by investigators using night-vision goggles (ATN Night Cougar LT). Then lights were turned on, and embryonic mouse hearts were microdissected in ice-cold PBS (Nacalai Tesque) under a stereomicroscope. The hearts were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. For real-time monitoring of bioluminescence from the embryonic hearts, homozygous Per2Luc knockin males (7) were mated with WT C57BL/6J females for one night, and E0.5 was defined as noon of the next day. Pregnant females were maintained under LD12:12 conditions until sampling. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee.

Detailed methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

RNA-Seq.

Mouse hearts were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), and RNA was extracted using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies), and samples with an RNA integrity number exceeding 8 were used. To average out variance in dissections and/or interindividual variance, equal amounts of total RNA from three individual E17–19 littermates were pooled at each time point as described previously (51). Since≈170 ng of total RNA was isolated from an E10 heart, seven hearts from E10–12 littermates were pooled at each time point before total RNA extraction to obtain more than 1 μg of total RNA. One microgram of pooled total RNA was used for polyA RNA selection using NEXTflex Poly (A) Beads (Bioo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Strand-specific sequencing libraries were constructed as described previously (52). Sequencing was performed by the Department of Computational Biology and Medical Sciences of the University of Tokyo, Tokyo on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument with 100-bp paired-end reads according to the manufacturer’s instructions. From the sequence reads, adaptor sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic (53). Then, sequence reads were mapped to the mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10) using STAR (54). To obtain reliable alignments, the reads with a mapping quality of less than 10 were removed by SAMtools (55). The University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) known canonical gene set (32,958 genes) was used for annotation, and the reads mapped to the exons were quantified using Homer (56) as described previously (51). Among the UCSC known canonical genes, we assumed that a gene was expressed if there were more than two reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped on average in the exons of the gene. RNA cycling was determined using Metacycle (57) with P < 0.05, rAMP >0.2, and the following options: minper = 20, maxper = 28, cycMethod = c (“ARS,” “JTK,” “LS”), analysisStrategy = “auto,” outputFile = TRUE, outIntegration = “both,” adjustPhase = “predictedPer,” combinePvalue = “fisher,” weightedPerPha = TRUE, ARSmle = “auto,” and ARSdefaultPer = 24. Previously published RNA-seq data (33) were used to determine cycling transcripts in young mouse hearts. Whole-transcriptome data (20) were used to analyze differentially expressed premiRNAs in nonrhythmic cultured cells. To quantify pre-microRNAs (premiRNAs) and miRNA host genes, miRBase (v21) and UCSC known canonical genes were used for annotation, respectively. EdgeR (58) was used to determine up-regulated miRNA genes (P < 0.02 and fold change >1.8). We assumed that a premiRNA was expressed if there were more than two and four reads per kilobase of the transcript per million mapped reads mapped (RPKM) on average for mRNA-seq and whole-transcriptome data, respectively. WebGestalt (59) was used for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis.

qRT-PCR.

Cultured cells were washed three times using ice-cold PBS. For ESCs, feeder cells were removed, and total RNA was extracted using an Isogen reagent (Nippon Gene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For mouse embryonic hearts, total RNA was isolated as described above, and 100 ng of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo). qPCR analysis was performed using a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) or iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The standard and fast PCR amplification protocols were used for cultured cells and tissues, respectively, followed by dissociation curve analysis to confirm specificity. Transcription levels were determined in duplicate and triplicate for mouse hearts and cultured cells, respectively, and were normalized to the level of Gapdh and 18S ribosomal RNA for mouse hearts and cultured cells, respectively. Primer sequences were used as described previously (20, 60).

Cell Culture.

ESC lines [KY1.1 (referred to as “WT” in the text), Per2Luc (7, 19, 61), Dnmt1−/−, Dnmt3a−/−, Dnmt3b−/−, and TKO (21, 62)] were used as described previously (20). Commercially available Dicer−/− and Dgcr8−/− ESCs (Novus Biologicals) were purchased. Mouse mGSC (mGS-DBA1) (35) and mouse iPSC (iPS-MEF-Ng-178B-5) (34) lines were provided by RIKEN BRC through the National Bio-Resource Project of MEXT, Japan. ESCs, mGSCs, and iPSCs were not further authenticated or tested for mycoplasma contamination after receipt. The cell lines are not listed in the International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) database. PSCs stably expressing the mouse Bmal1 promoter-driven luciferase reporters or mouse Per2 promoter-driven luciferase reporters were established as described previously (19, 20). Briefly, 3 µg of mBmal1:luc-pT2A or mPer2:luc-pT2A plasmid with a Zeocin selection marker and 1 µg of a Tol2 transposase expression vector (pCAGGS-TP) were diluted in 40 µL of culture medium and 12 µL of FuGENE 6 (Promega) and were mixed well. After a 15-min incubation period at room temperature, the mixture was added to 2–2.5 × 105 cells. The cells were selected using 10 µg/mL Zeocin (Invitrogen). For mPer2:luc-pT2A plasmid with a Zeocin selection marker, a total of 0.4 kb of the 5′-flanking region of the mouse Per2 gene was cloned from mouse genomic DNA by PCR and inserted into BglII/HindIII sites of pT2A vector. PSCs were cultured on a feeder layer of mitomycin C-treated primary MEFs in an ES medium (ESM) that comprised Glasgow Minimum Essential Medium (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) supplemented with 15% FBS (HyClone, GE Healthcare), 0.1 mM Eagle's minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids (Nacalai Tesque), 100 µM StemSure 2-Mercaptoethanol solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 1,000 units/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and 100 units/mL penicillin–streptomycin (Nacalai Tesque).

Clock- and Npas2-deficient ESCs were generated from Per2Luc ESCs using the CRISPR/Cas9 system as described previously (63). The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) target sites were determined using the CRISPR Design Tool developed by Feng Zhang’s group (64). A pair of oligos for the sgRNA targeting site were annealed and inserted into the sgRNA plasmid. The oligos were as follows: Clock-s, 5′-CACCGACCCCAGCTCCTTAATG-3′; Clock-as, 5′-AAACCATTAAGGAGCTGGGGTC-3′; Npas2-s, 5′-CACCGCCTGGTAACACTCGGAAAA-3′; and Npas2-as, 5′-AAACTTTTCCGAGTGTTACCAGGC-3′. The ESCs were cotransfected with an hCas9 expression vector, sgRNA expression vectors, and a plasmid with a puromycin selection marker (PB510B-1; System Biosciences) using FuGENE HD (Promega). The cells were selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 2 d, and then colonies were picked and checked by sequencing the genomic DNA.

For Clock rescue or overexpression experiments, Clock cDNA from Clock pcDNA3.1 (65) was cloned into a PB-TET vector (31). The dKO ESCs or Per2Luc ESCs were transfected using 16.5 µL of FuGENE 6 mixed with 1 µg of pCAG-PBase (20), 3 µg of PB-TET-Clock, 1 µg of PB-CAG-rtTAAdv (20), and 0.5 µg of PB510B-1. The transfected cells were cultured in ESM containing 2 µg/mL puromycin for 2 d. The ESC colonies were picked and checked by qRT-PCR or immunostaining. For Clock rescue, the ESCs were treated with 100 ng/mL doxycycline. For Clock overexpression, the ESCs were treated with 500 ng/mL doxycycline.

In Vitro Differentiation.

In vitro differentiation of PSCs was performed as described previously (20, 66). After PSCs were trypsinized and feeder cells were removed, embryoid bodies (EBs) were generated by harvesting 2,000 cells and seeding them onto low-attachment 96-well plates (Lipidure Coat; NOF) in a differentiating medium without LIF supplementation (EFM), which comprised high-glucose DMEM (Nacalai Tesque) containing 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, GlutaMAX-I (Invitrogen), 100 µM StemSure 2-mercaptoethanol solution, and 100 units/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Two days later, EBs were plated onto gelatin-coated tissue-culture 24-well plates and were grown for several additional weeks. The EFM was changed every 1–2 d.

Real-Time Bioluminescence Analysis.

For cell lines, real-time bioluminescence analysis was performed as described previously (20). Briefly, the cell lines were seeded in 24-well black plates or 35-mm culture dishes, and the medium was replaced with phenol red-free EFM or ESM containing 0.2 mM luciferin (Promega), 10 mM Hepes, and 100 nM Dex (Sigma-Aldrich) before measuring began. The culture plates were set on a turntable in an in-house–fabricated real-time monitoring system developed by Takao Kondo (65). The bioluminescence from each well was counted for 1 min at 20-min intervals. The strength of rhythmicity was defined using spectral analysis (FFT relative power) with relative spectral power density peaking at 21–26 h.

Ex Vivo Culture of Embryonic Mouse Hearts.

Embryonic mouse hearts were microdissected in ice-cold HBSS (Nacalai Tesque) under a stereomicroscope in the daytime [zeitgeber time 3 (ZT3)] or night (ZT14), cultured in DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium (Nacalai Tesque) containing 10% FBS (Corning), 0.2 mM luciferin, 100 units/mL penicillin-streptomycin with 0.4-μm Millicell inserts (Millipore). Then the bioluminescence was monitored immediately without Dex or Fsk stimuli as described above. For Fsk or Dex stimulation, the E10 hearts were incubated with DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium containing the same ingredients and 10 μM Fsk or 100 nM Dex for 1 h at 37 °C, and then the medium was replaced with fresh medium without Fsk and Dex.

Single-Cell Bioluminescence Analysis.

For dispersed cardiomyocyte culture, microdissected embryonic hearts were washed with ice-cold HBSS without Mg2+ and Ca2+ (Nacalai Tesque). The cells were dissociated at 37 °C for 15 min with 0.25% (wt/vol) trypsin in HBSS without Mg2+ and Ca2+. Trypsin digestion was terminated by adding DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium containing the same ingredients. The cells were centrifuged and resuspended in DMEM/Ham’s F-12 medium containing the same ingredients. To exclude nonmuscle cells, the isolated cells were first plated onto tissue-culture dishes at 37 °C for 2 h under a water-saturated atmosphere of 5% CO2 based on the observation that nonmuscle cells attach to the substrata more rapidly (67). The suspended cells were then collected and plated onto a fibronectin-coated glass-bottomed dish (Iwaki). After overnight culture for cell attachment and confirmation of beating, cardiomyocytes were accumulated, and the dish was set on the stage of an LV-200 microscopic image analyzer (Olympus).

For real-time bioluminescence analysis of 28-d differentiated WT, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs, cells were plated in 35-mm culture dishes. After cell attachment, the medium was replaced with EFM without phenol red containing 10 mM Hepes and 0.2 mM luciferin. The dish was set on the stage of an LV-200 microscopic image analyzer (Olympus). Time-lapse images were collected with 5–20 min exposures at 60-min intervals. The strength of rhythmicity was defined using spectral analysis (FFT relative power) with relative spectral power density peaking at 21–26 h.

Immunostaining.

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and then were embedded in paraffin (Tokyo Central Pathology Laboratory). The hearts were sectioned into 5-µm-thick slices using a rotary microtome (Leica) and were used for immunostaining by CLSP4 anti-CLOCK mouse monoclonal antibody (1:500 dilution) [a kind gift from Hikari Yoshitane and Yoshitaka Fukada, University of Tokyo, Tokyo (68)] overnight for three nights at 4 °C after the inactivation of endogenous peroxidase. Then they were incubated with a biotinylated anti-mouse antibody with an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories), and the peroxidase was visualized using an ImmPACT DAB peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories). The images were acquired using a BZ-X710 microscope (KEYENCE). The images shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence staining of cultured cells was performed as described previously (20). Briefly, cells plated on coverslips were fixed with cold methanol. After washing with PBS, cells were blocked with 5% skim milk and then were incubated with an anti-CLOCK antibody (CLSP4) overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS, the cells were incubated with a secondary antibody, and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Nacalai Tesque). The cells were washed in PBS and mounted with PermaFluor Mounting Medium (Thermo Scientific). The cells were observed using an LSM510 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss). The images shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Western Blotting.

Cells or tissues were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton-X100, 1 mM DTT, cOmplete Mini protease inhibitor (Roche), 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4. Lysates were sonicated and clarified by centrifugation. The samples were resolved on SDS/PAGE using 5% polyacrylamide gels for PER1 proteins or 7.5% gel for the other proteins and were blotted with a primary antibody: CLSP4 anti-CLOCK antibody (1:5,000) (68), anti-BMAL1 (1:5,000) (20), anti-PER1 (1:3,000) (GTX129596; GeneTex), anti-PER2 (1:5,000) (PER21-A; Alpha Diagnostic), anti-CRY1 (1:6,000) (CRY11-A; Alpha Diagnostic), anti-CRY2 (1:3,000) (CRY21-A; Alpha Diagnostic), anti–β-actin (1:20,000) (Sigma-Aldrich), or anti–α-tubulin (1:10,000) (MBL). All Western blots shown except those in Figs. 4C and 5B (n = 1) are representative for at least two independent experiments.

Dual Luciferase Assay.

The 5′ or 3′ UTR of mouse Clock mRNA was amplified from mRNA or genomic DNA. The 345-bp or 4.5-kb PCR fragment was cloned into pGL4.53[luc2/PGK] or pmirGLO vectors (Promega), respectively, and the sequences were confirmed. For miRNA expression constructs, the sequences corresponding to the rna22-predicted miRNAs (43) were cloned into miRNA pmR-ZsGreen1 (Takara Bio). After feeder cells were removed, MEFs or WT, Dicer−/−, and Dgcr8−/− ESCs were seeded into each well of 24-well plates. For differentiated ESCs, the cells differentiated in vitro for 27 d were trypsinized and passaged to newly prepared dishes. One hundred fifty nanograms of reporters and 1,500 ng of the indicated miRNA expression vectors or 150 ng of reporters were prepared for each triplicate and were cotransfected using a 3:1 ratio of FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (in microliters) to DNA (in micrograms). Renilla luciferase was used for the internal normalization. pmirGLO used for the 3′ UTR reporter encodes Renilla luciferase as a second reporter, and pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase; Promega) was used for 5′ UTR reporter assays. Lysates were harvested 24 h after transfection, and reporter activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay (Promega). Data were normalized by dividing firefly luciferase activity by that of Renilla luciferase, and the mean of the ratio of each luciferase reporters with the control vector plasmid was set to 1.

Single-Molecule RNA-FISH.

Cells cultured on 18-mm round cover glasses were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer solution (Nacalai Tesque) for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with 70% ethanol for 1 h at 4 °C. After incubation with wash buffer composed of 10% formamide (Nacalai Tesque) and 2× SSC (Nacalai Tesque) at room temperature for 2–5 min, the cells were hybridized with 100 μL of hybridization buffer [100 mg/mL dextran sulfate (Nacalai Tesque) and 10% formamide in 2× SSC] containing 125 nM Stellaris FISH probes labeled with Quasar 670 dye listed in Dataset S4 within the humidified chamber at 37 °C for 16 h. The cells were incubated with 1 mL wash buffer at 37 °C for 30 min, counterstained with 1 mL wash buffer containing Hoechst 33342 at 37 °C for 30 min, washed with 1 mL 2× SSC at room temperature for 2–5 min, and mounted with PermaFluor Mounting Medium. Images were acquired using an LSM510 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by the statistical methods stated in each legend using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 software or R. The Shapiro–Wilk test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of data. ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons tests were performed after the equality of variance was determined by a Brown–Forsythe test. Statistical significance was set to P < 0.01 or P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Inokawa of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine for valuable discussions and technical support; Drs. H. Yoshitane and Y. Fukada of the University of Tokyo for kindly providing the anti-CLOCK antibodies; Dr. Takashi Shinohara of Kyoto University for providing mGSCs; and Dr. Yutaka Suzuki of the University of Tokyo for supporting RNA-seq. This work was supported in part by Grants-In-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to Y.U., N.K., Y.T., and K.Y.), the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to N.K.), the Takeda Science Foundation (to K.Y.), and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research JP221S0002 (to K.Y.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The RNA-seq data reported in this paper have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of the Japan Sequence Read Archive (DRA) (accession no. DRA005754).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1703170114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Genetics of circadian rhythms in mammalian model organisms. Adv Genet. 2011;74:175–230. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387690-4.00006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bass J. Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491:348–356. doi: 10.1038/nature11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masri S, Sassone-Corsi P. The circadian clock: A framework linking metabolism, epigenetics and neuronal function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:69–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsalobre A, Damiola F, Schibler U. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell. 1998;93:929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki S, et al. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science. 2000;288:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagita K, Tamanini F, van Der Horst GT, Okamura H. Molecular mechanisms of the biological clock in cultured fibroblasts. Science. 2001;292:278–281. doi: 10.1126/science.1059542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo SH, et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogenesch JB, Ueda HR. Understanding systems-level properties: Timely stories from the study of clocks. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:407–416. doi: 10.1038/nrg2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:164–179. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preitner N, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ukai-Tadenuma M, et al. Delay in feedback repression by cryptochrome 1 is required for circadian clock function. Cell. 2011;144:268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez JD, Chen D, Storer E, Sehgal A. Non-cyclic and developmental stage-specific expression of circadian clock proteins during murine spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:81–91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.011833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse D, Cermakian N, Brancorsini S, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P. No circadian rhythms in testis: Period1 expression is clock independent and developmentally regulated in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:141–151. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amano T, et al. Expression and functional analyses of circadian genes in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos: Cry1 is involved in the meiotic process independently of circadian clock regulation. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:473–483. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reppert SM, Schwartz WJ. Maternal suprachiasmatic nuclei are necessary for maternal coordination of the developing circadian system. J Neurosci. 1986;6:2724–2729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-09-02724.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis FC, Gorski RA. Development of hamster circadian rhythms: Role of the maternal suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 1988;162:601–610. doi: 10.1007/BF01342635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jud C, Albrecht U. Circadian rhythms in murine pups develop in absence of a functional maternal circadian clock. J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:149–154. doi: 10.1177/0748730406286264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowalska E, Moriggi E, Bauer C, Dibner C, Brown SA. The circadian clock starts ticking at a developmentally early stage. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25:442–449. doi: 10.1177/0748730410385281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagita K, et al. Development of the circadian oscillator during differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3846–3851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913256107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umemura Y, et al. Transcriptional program of Kpna2/Importin-α2 regulates cellular differentiation-coupled circadian clock development in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E5039–E5048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419272111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Porath I, et al. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee TI, Young RA. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 2013;152:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnishi K, et al. Premature termination of reprogramming in vivo leads to cancer development through altered epigenetic regulation. Cell. 2014;156:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasuhara N, et al. Triggering neural differentiation of ES cells by subtype switching of importin-alpha. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:72–79. doi: 10.1038/ncb1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuhara N, et al. Importin alpha subtypes determine differential transcription factor localization in embryonic stem cells maintenance. Dev Cell. 2013;26:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmberg J, Perlmann T. Maintaining differentiated cellular identity. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:429–439. doi: 10.1038/nrg3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sumová A, et al. Circadian molecular clocks tick along ontogenesis. Physiol Res. 2008;57(Suppl 3):S139–S148. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolatshad H, Cary AJ, Davis FC. Differential expression of the circadian clock in maternal and embryonic tissues of mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inada Y, et al. Cell and tissue-autonomous development of the circadian clock in mouse embryos. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landgraf D, Achten C, Dallmann F, Oster H. Embryonic development and maternal regulation of murine circadian clock function. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32:416–427. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.986576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: Implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16219–16224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell. 2004;119:1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeBruyne JP, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. Peripheral circadian oscillators require CLOCK. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R538–R539. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeBruyne JP, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. CLOCK and NPAS2 have overlapping roles in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:543–545. doi: 10.1038/nn1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chekulaeva M, Filipowicz W. Mechanisms of miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation in animal cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: Mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruber AJ, et al. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs contribute to pluripotency by inhibiting regulators of multiple differentiation pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9313–9326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miranda KC, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loudon AS. Circadian biology: A 2.5 billion year old clock. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R570–R571. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pando MP, Morse D, Cermakian N, Sassone-Corsi P. Phenotypic rescue of a peripheral clock genetic defect via SCN hierarchical dominance. Cell. 2002;110:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serón-Ferré M, et al. Circadian rhythms in the fetus. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;349:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prasanth KV, et al. Regulating gene expression through RNA nuclear retention. Cell. 2005;123:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landgraf D, Wang LL, Diemer T, Welsh DK. NPAS2 compensates for loss of CLOCK in peripheral circadian oscillators. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morf J, et al. Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein modulates circadian gene expression posttranscriptionally. Science. 2012;338:379–383. doi: 10.1126/science.1217726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lerner I, et al. Clk post-transcriptional control denoises circadian transcription both temporally and spatially. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7056. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koike N, et al. Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals. Science. 2012;338:349–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi JS, et al. ChIP-seq and RNA-seq methods to study circadian control of transcription in mammals. Methods Enzymol. 2015;551:285–321. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu G, Anafi RC, Hughes ME, Kornacker K, Hogenesch JB. MetaCycle: An integrated R package to evaluate periodicity in large scale data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3351–3353. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]