Background: Maf1 is a central repressor of genes that promote oncogenesis, yet little is known about how Maf1 is regulated.

Results: Maf1K35 SUMO modification is controlled by SENP1, affecting its ability to repress transcription and suppress cell growth.

Conclusion: SUMOylation of Maf1 is implicated as a regulatory mechanism for RNA pol III transcription.

Significance: A link between SENP1, Maf1, and RNA pol III-mediated transcription in oncogenesis is revealed.

Keywords: Post-translational Modification, RNA Polymerase III, Transcription Factors, Transcription Regulation, Transcription Repressor

Abstract

RNA polymerase (pol) III transcribes genes that determine biosynthetic capacity. Induction of these genes is required for oncogenic transformation. The transcriptional repressor, Maf1, plays a central role in the repression of these and other genes that promote oncogenesis. Our studies identify an important new role for SUMOylation in repressing RNA pol III-dependent transcription. We show that a key mechanism by which this occurs is through small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) modification of Maf1 by both SUMO1 and SUMO2. Mutation of each lysine residue revealed that Lys-35 is the major SUMOylation site on Maf1 and that the deSUMOylase, SENP1, is responsible for controlling Maf1K35 SUMOylation. SUMOylation of Maf1 is unaffected by rapamycin inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mTOR-dependent Maf1 phosphorylation. By preventing SUMOylation at Lys-35, Maf1 is impaired in its ability to both repress transcription and suppress colony growth. Although SUMOylation does not alter Maf1 subcellular localization, Maf1K35R is defective in its ability to associate with RNA pol III. This impairs Maf1 recruitment to tRNA gene promoters and its ability to facilitate the dissociation of RNA pol III from these promoters. These studies identify a novel role for SUMOylation in controlling Maf1 and RNA pol III-mediated transcription. Given the emerging roles of SENP1, Maf1, and RNA pol III transcription in oncogenesis, our studies support the idea that deSUMOylation of Maf1 and induction of its gene targets play a critical role in cancer development.

Introduction

RNA polymerase (pol)2 III transcribes a variety of small untranslated RNAs, including tRNAs, 5 S rRNAs, U6 RNA, and 7SL RNA. RNA pol III products have important functions in protein synthesis, protein trafficking, and RNA processing. Enhanced expression of these genes is a hallmark of human cancers, and this has been shown to be required for cellular transformation and tumorigenesis (1, 2). Maf1 is a transcription repressor that was first characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a central node for repression of RNA pol III-dependent gene expression (3, 4). Yeast Maf1 represses transcription initiation via its interaction with RNA pol III, which induces a conformational change that impairs the ability of RNA pol III to associate with TBP and Brf1 (5). In addition, Maf1 prevents transcription reinitiation by binding to RNA pol III during elongation (5). In contrast to yeast Maf1, mammalian Maf1 has broader functions including direct regulation of both RNA pol III-dependent and pol II-dependent transcription (6). Maf1 represses the expression of TBP, the central transcription initiation factor. Maf1-mediated decreases in TBP may also indirectly repress RNA pol I-dependent rDNA genes, as well as other genes, that can be limiting for TBP. Increased cellular concentrations of TBP have been shown to induce cell proliferation (7) and oncogenic transformation (8). The fact that Maf1 represses genes involved in oncogenesis and that it suppresses anchorage-independent growth (6) suggests that Maf1 may function as a tumor suppressor. This underscores the importance of understanding the molecular mechanisms that control Maf1 function.

SUMOylation is the covalent attachment of the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to a lysine residue in the target protein. SUMOylation is a multistep enzymatic process that involves the heterodimeric E1 activating enzymes, SAE1/SAE2, the conjugating E2 enzyme, Ubc9, and a number of E3 ligases (9). Additionally, sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) are required to process SUMO into mature forms and to remove SUMO from target proteins. Of the three characterized SUMO isoforms, SUMO1 shares 45% similarity with SUMO2 and SUMO3, which are 96% similar. The emerging theme in the mechanism of SUMO-dependent transcriptional regulation is that it plays a prominent role in the silencing of specific RNA pol II-transcribed genes (10). As protein targets of SUMOylation have key functions in cellular growth, DNA damage repair, and cell survival, deregulation of this system is thought to play an important role in cancer progression. Emerging studies show that aberrant expression of the SUMOylation components appears to contribute to tumorigenesis in a context-dependent manner.

Although SUMOylation of transcription components plays an important role in modulating RNA pol II-dependent transcription, whether SUMOylation might affect either RNA pol I-mediated or pol III-mediated transcription processes has not been examined. Our study reveals a new role for SUMOylation in the repression of RNA pol III-transcribed genes and identifies Maf1 as a key target in this response. As Maf1 can suppress cellular transformation (6), its regulation is likely to be critical in determining the oncogenic state of cells. However, little is known regarding how mammalian Maf1 is regulated. Studies revealed that Maf1 is phosphorylated by mTOR, which modestly alters its ability to repress transcription (11, 12), yet the mechanism by which this controls Maf1 function is not known. Here we demonstrate that modification of Maf1 by SUMO at Lys-35 is an important mechanism that contributes to the SUMO-mediated repression of RNA pol III-transcribed genes. The amount of Maf1 that is SUMOylated is determined by the deSUMOylase SENP1, and this controls the ability of Maf1 to associate with RNA pol III to repress transcription. As SENP1 is up-regulated in several human cancers and plays a critical role in oncogenesis (13), our results provide a new molecular link between the deregulation of SENP1, the deSUMOylation and inactivation of Maf1, and induction of RNA pol III-mediated transcription in promoting oncogenic transformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Reagents

U87, COS7, and 293T cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Expression plasmids for Myc-SUMO1ρ and Myc-SUMO2ρ, which are relatively resistant to deSUMOylases, were kindly provided by Dr. David Ann. The pcDNA3-Maf1HA expression vector was previously described (6). Ubc9 and SENP1 siRNAs were previously described (14, 15). COS7 and 293T cells were transfected using F1 transfection reagent (Targeting Systems) as per the manufacturer's protocol. U87 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described previously (16). For transfection of small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotide sequences, the Targeting Systems siRNA kit was used following the protocol provided. Rapamycin (MP Biomedicals) was diluted in DMSO to a final concentration of 100 μm.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Maf1 mutants were generated using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Primers for mutagenesis were designed using the Stratagene QuikChange primer design software. Mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing at the University of Southern California (USC)/Norris Microchemical Core.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated (RNA-STAT 60, Tel-Test) from cells 48 h after transfection followed by DNase treatment (Turbo DNA-free kit, Ambion). The RNAs were reverse-transcribed to cDNA (SuperScript III first strand synthesis kit, Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed on the Mx3000P quantitative PCR system (Brilliant SYBR Green quantitative PCR master mix, Stratagene) with primer sets for U6, GAPDH, 7SL, and pre-tRNALeu as described previously (6, 17). The primer sequences for pre-tRNAiMet are: forward, 5′-CTGGGCCCATAACCCAGAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGGTAGCAGAGGATGGTTTC-3′; for Maf1, the primer sequences are: forward, 5′-GTGGAGACTGGAGATGCCCA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CTGGGTTATAGCTGTAGATGTCACA-3′. Relative amounts of transcripts were quantified by the comparative threshold cycle method (ΔΔCt) with GAPDH as the endogenous reference control.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared 48 h after transfection in cell lysis buffer and 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma) and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described previously (16) using antibodies to the following: HA (Roche Applied Science), Myc, SUMO1, SUMO2, RNA polymerase III (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Ubc9 (Cell Signaling), Maf1, SENP1 (Abgent), and β-actin (Millipore). Bound primary antibody was visualized using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce) or biotinylated secondary antibodies complexed with avidin/peroxidase (Vector Laboratories) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce and PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Densitometry was performed using UN-SCAN-IT software (Silk Scientific). Phos-tag acrylamide (Wako Chemicals) was used as per the manufacturer's protocol. For immunoprecipitation reactions, cell lysates were incubated with 4–10 μg of antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Bound antibody complexes were incubated with protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 3 h at 4 °C. Washes were carried out with cell lysis buffer and eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer.

Immunofluorescence

U87 cells transfected with HA-tagged wild type Maf1 or Maf1K35R were plated on collagen-coated coverslips. 24 h after transfection, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde and incubated with HA antibody (Covance) for 30 min. Following incubation with primary antibody, cells were washed and then incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) for 30 min. Cells were then washed and mounted in mounting medium with propidium iodide (Vector Laboratories). Imaging was carried out on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope.

Colony Growth Suppression Assay

U87 cells were transfected with HA-tagged wild type Maf1 or Maf1K35R expression vectors and a puromycin-resistant vector. 48 h after transfection, colonies were selected by treatment with puromycin. Medium with fresh puromycin was changed every 48 h. 3 weeks after selection, colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described previously (16). Briefly, after cross-linking and sonication, chromatin was immunoprecipitated using antibodies to HA (Abcam), RPC39 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and IgG (Bethyl Laboratories) overnight. DNA was isolated and amplified by quantitative PCR using the Kappa SYBR reagent (Kappa Biosystems) on the MX3000P system. The threshold Ct values were normalized to the PCR efficiency as described previously (16). Normalized Ct values for antibody pulldowns were then normalized to input and IgG. -Fold changes in occupancy were calculated after setting the promoter occupancy in the vector-transfected cells to 1.

RESULTS

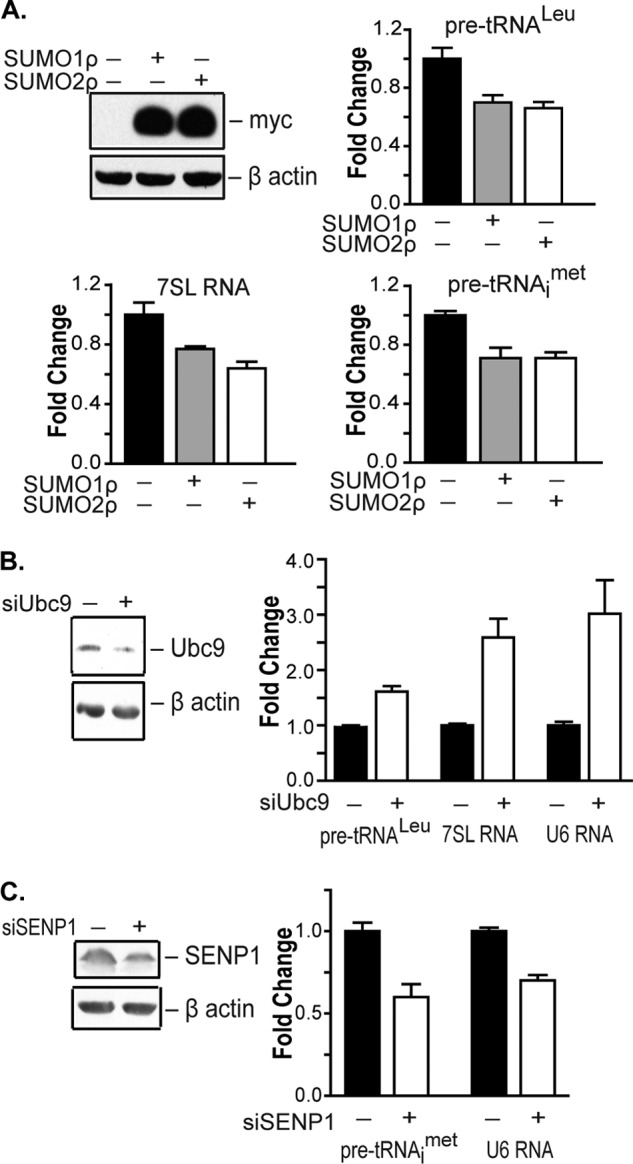

Increased Cellular SUMOylation Represses RNA Polymerase III-dependent Transcription

We examined the potential role for SUMOylation in modulating RNA pol III-mediated transcription. Myc-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2 was expressed in U87 glioblastoma cells to globally increase the SUMOylation of cellular proteins. Increased expression of either SUMO1 or SUMO2 resulted in a decrease in expression of RNA pol III-dependent pre-tRNALeu, pre-tRNAiMet, and 7SL RNA transcripts (Fig. 1A). Consistent with these results, decreased expression of the only SUMO-conjugating enzyme, Ubc9, resulted in an increase in RNA pol III-dependent transcription (Fig. 1B). Given recent studies revealing that the SUMO isopeptidase, SENP1, has oncogenic properties and is overexpressed in human cancers (13), we tested whether altered expression of SENP1 could modulate RNA pol III-mediated transcription. Decreased expression of SENP1 resulted in a reduction of tRNA and U6 RNA transcripts (Fig. 1C). Thus, changes in cellular SUMOylation through altered expression of SUMO, Ubc9 or SENP1 all modulate RNA pol III-dependent transcription. These results support the idea that enhanced cellular SUMOylation negatively regulates RNA pol III-mediated gene expression.

FIGURE 1.

SUMOylation affects RNA pol III-dependent transcription. A, enhanced cellular SUMOylation represses RNA pol III-dependent transcription. U87 cells were transfected with empty vector, Myc-SUMO1ρ, or SUMO2ρ as indicated. qRT-PCR analysis was performed with pre-tRNALeu, pre-tRNAiMet, 7SL RNA, and GAPDH primers. -Fold changes are statistically significant: analysis of variance, pre-tRNALeu, p = 0.001; pre-tRNAiMet, p = 0.0059; 7SL RNA, p = 0.0061. Protein lysates were immunoblotted with Myc and β-actin antibodies. B, decreased Ubc9 expression induces RNA pol III-dependent transcription. COS7 cells were transfected with mismatch siRNA or Ubc9 siRNA. qRT-PCR analysis was performed as described in A. -Fold changes are statistically significant: Student t test, pre-tRNALeu, p < 0.0001; 7SL RNA, p = 0.0001; U6 RNA, p = 0.0013. Protein lysates were immunoblotted with Ubc9 and β-actin antibodies. C, decreased SENP1 expression represses RNA pol III-dependent transcription. U87 cells were transfected with mismatch siRNA or SENP1 siRNAs. qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using pre-tRNAiMet, U6 RNA, and GAPDH primers. -Fold changes are statistically significant: Student t test, pre-tRNAiMet, p = 0.0017; U6 RNA, p < 0.0001. Protein lysates were immunoblotted with SENP1 and β-actin antibodies. For all experiments, gene expression was quantified relative to GAPDH as an internal control. Values shown are the means ± S.E. (n = 3).

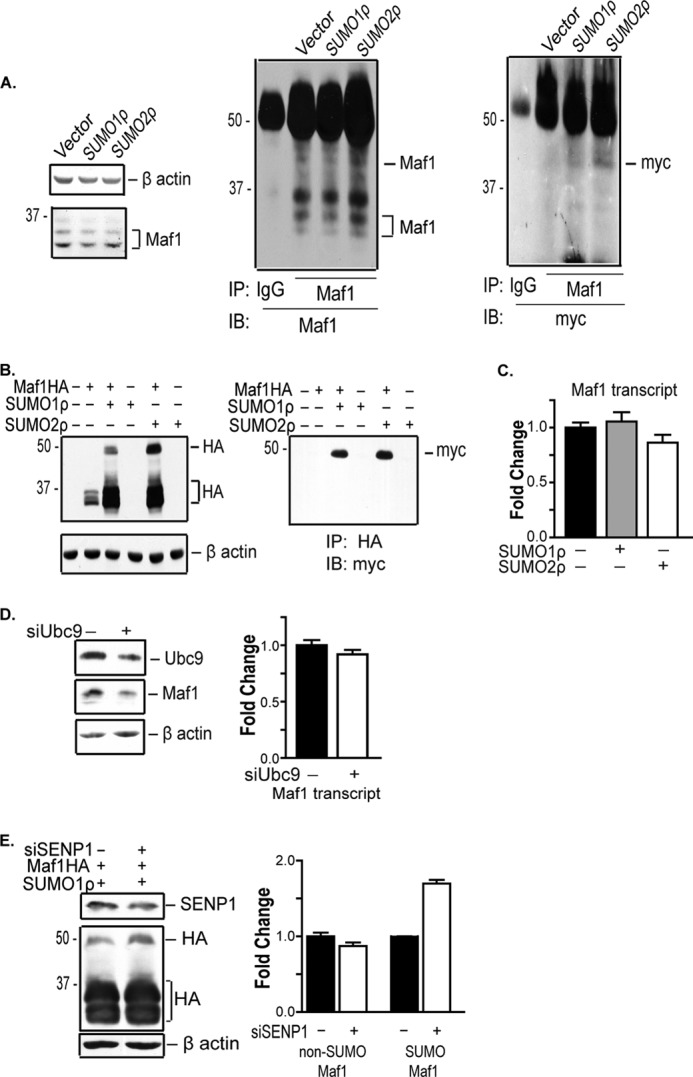

SUMOylation Increases Maf1 Expression and Covalently Modifies Maf1

Because Maf1 is a negative regulator of RNA pol III-dependent genes, we investigated whether SUMOylation affects Maf1. To determine whether Maf1 was covalently modified by SUMO, 293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2 expression vectors. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Maf1 antibodies and immunoblotted with antibodies to Maf1 and Myc (Fig. 2A). This revealed a new higher molecular mass band with an apparent molecular mass of 46 kDa, in addition to the normally observed Maf1 polypeptides. Immunoblot analysis with Myc antibodies revealed that the higher molecular mass band represented SUMOylated Maf1. To further confirm that Maf1 is modified by SUMO, an HA-tagged Maf1 expression vector was coexpressed with Myc-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2. Immunoblot analysis revealed an increase in Maf1 upon the expression of either SUMO1 or SUMO2. A higher molecular mass band was also detected with Myc antibodies (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Maf1 is SUMOylated by SUMO1 and SUMO2. A, endogenous Maf1 is SUMOylated. 293T cells were transfected with Myc-SUMO1ρ or SUMO2ρ expression vectors. Cell extracts were immunoblotted (IB) with Maf1 and β-actin antibodies or immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Maf1 antibodies and immunoblotted with Maf1 or Myc antibodies (n = 3). B, ectopically expressed Maf1 is SUMOylated. COS-7 cells were transfected with wild type Maf1-HA and Myc-SUMO1ρ or SUMO2ρ expression vectors were co-transfected, where indicated. Cell extracts were immunoblotted with HA or β-actin antibodies. Lysates from above were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibody. C, enhanced cellular SUMOylation does not affect Maf1 mRNA expression. COS7 cells were transfected with Myc-SUMO1ρ or Myc-SUMO2ρ expression vectors. qRT-PCR was performed using Maf1 and GAPDH primers. Gene expression was quantified relative to GAPDH as an internal control. Values shown are the means ± S.E. (n = 3). D, down-regulation of Ubc9 results in a decrease in Maf1 protein expression. COS7 cells were transfected with mismatch siRNA or Ubc9 siRNA. Protein lysates were immunoblotted with Ubc9, Maf1, and β-actin antibodies, respectively (n = 3). qRT-PCR was performed using Maf1 and GAPDH primers. Gene expression was quantified relative to GAPDH as an internal control. Values shown are the means ± S.E. (n = 3). E, decreased expression of SENP1 enhances the amount of SUMOylated Maf1. U87 cells were transfected with Maf1-HA and Myc-SUMO1ρ expression vectors and SENP1 siRNA as indicated. Cells transfected with mismatch siRNA were used as a negative control. Lysates were immunoblotted with HA, SENP1, and β-actin antibodies. The -fold change in SUMOylated and non-SUMOylated Maf1-HA was calculated by normalizing to β-actin where the control is set to 1. Values shown are the means ± S.E. (n = 3).

We next determined whether alterations in the expression of SUMO-conjugating and -deconjugating enzymes would affect Maf1 expression or covalent SUMO modification. Overexpression of SUMO1 or SUMO2 in COS7 cells (Fig. 2C) and 293T cells (data not shown) showed no significant effect on Maf1 mRNA expression. Reduced Ubc9 expression resulted in a corresponding decrease in endogenous Maf1 protein, but no changes in Maf1 mRNA were observed (Fig. 2D). Decreased expression of the SUMO-deconjugating enzyme, SENP1, did not alter overall Maf1 expression but did result in an increase in the fraction of SUMOylated Maf1 (Fig. 2E). Together, these results identify a new molecular event by which Maf1 is modified. Furthermore, the amount of SUMOylated Maf1 is determined by the SUMO-deconjugating enzyme, SENP1. In addition, SUMO modification of Maf1 can be uncoupled from other cellular SUMOylation events that affect Maf1 expression.

Lys-35 Is the Major Site of SUMOylation on Maf1

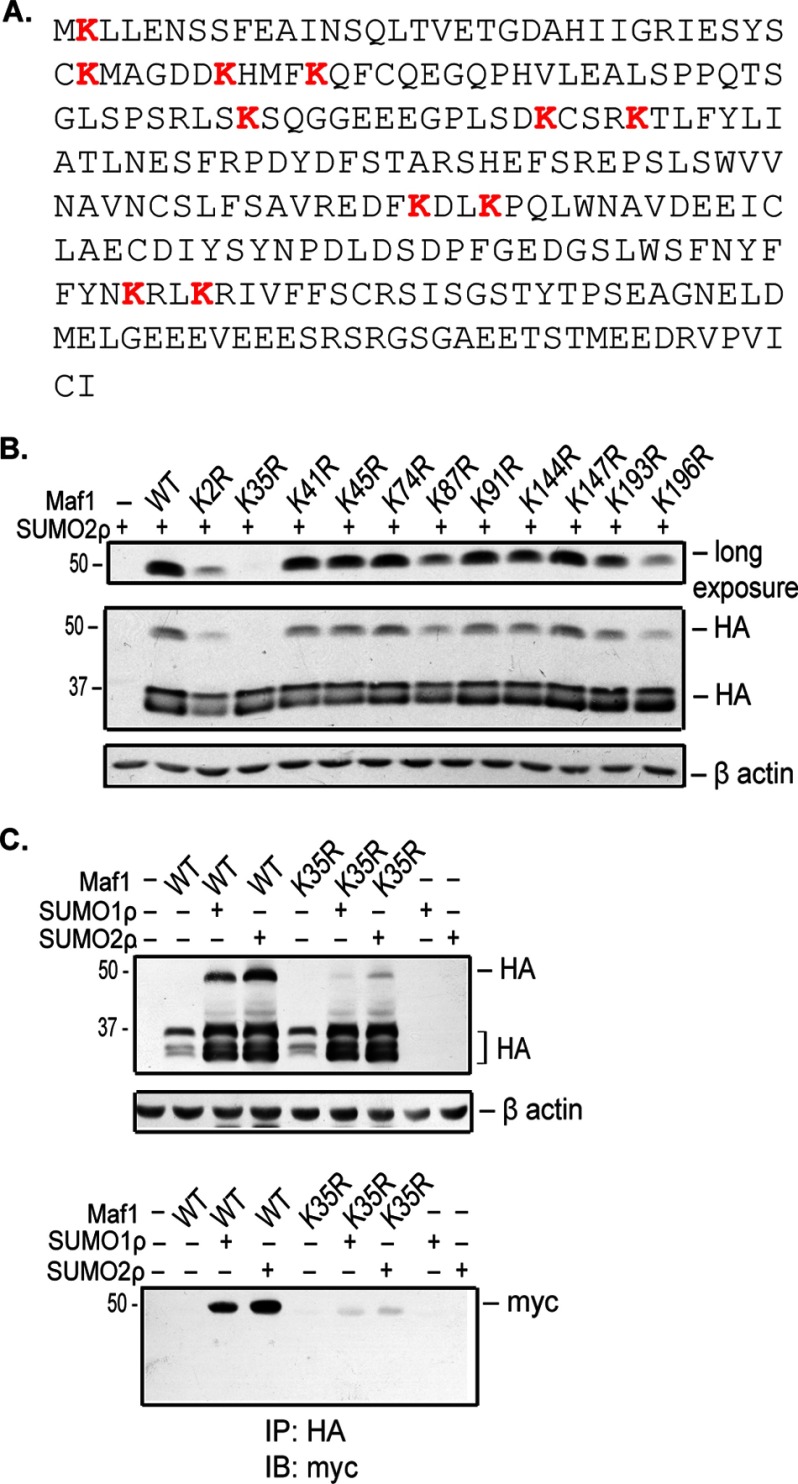

SUMO is most often conjugated to a lysine residue that lies within the SUMO consensus motif, ΨKX(E/D). However, analysis of the Maf1 protein sequence revealed that it does not possess a SUMO consensus motif (Fig. 3A). Therefore, to determine the residues that were covalently modified by SUMO, we mutated each of the 11 Lys residues to Arg by site-directed mutagenesis and performed a cell-based SUMOylation assay with Myc-tagged SUMO2 in COS7 cells. All Maf1 mutants, with the exception of Maf1K2R, were expressed at levels comparable with the Maf1 wild type (WT) protein. Upon expression of Myc-tagged SUMO2, all of the mutant proteins were capable of forming the higher molecular weight SUMOylated polypeptide with the exception of Maf1K35R (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Maf1 is SUMOylated at lysine 35. A, amino acid sequence of Maf1. Lysine residues are highlighted in red. B, analysis of Maf1 lysine mutations. COS-7 cells were transfected with wild type Maf1-HA or Maf1HA mutants and Myc-SUMO2ρ expression vectors as indicated. Cell extracts were immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies. C, SUMOylation of Maf1 predominantly occurs at Lys-35. COS7 cells were transfected with either wild type Maf1HA or Maf1HAK35R and Myc-SUMO1ρ or SUMO2ρ expression vectors. Lysates were immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies or first immunoprecipitated (IP) with HA antibody and immunoblotted (IB) with Myc antibody.

To confirm that Lys-35 is the major site of SUMOylation on Maf1 by both SUMO1 and SUMO2, we coexpressed Myc-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2 with HA-tagged Maf1WT or Maf1K35R. Expression of either SUMO1 or SUMO2 resulted in the enhanced expression of both Maf1WT and Maf1K35R. However, Maf1K35R showed a marked decrease in the higher molecular weight SUMOylated polypeptides when compared with Maf1WT in both COS7 (Fig. 3C, top panel) and U87 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of protein lysates with HA antibodies followed by immunoblot analysis with Myc antibodies demonstrated a substantial loss of SUMOylated Maf1K35R when compared with Maf1WT (Fig. 3C, bottom panel). Hence, Lys-35 is the major site of SUMOylation on Maf1 by both SUMO1 and SUMO2.

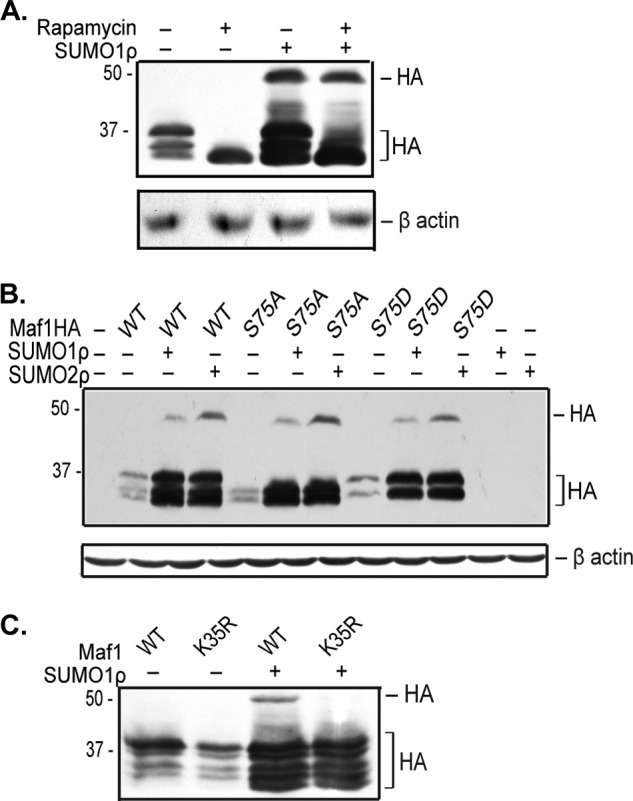

Maf1 Phosphorylation at Ser-75 and SUMOylation at K35R Are Independent Events

Previous studies have shown that mTOR kinase phosphorylates mammalian Maf1 (12, 18). We determined whether mTOR kinase affects Maf1 SUMOylation. Rapamycin treatment was used to inhibit the mTOR kinase pathway. Cell-based SUMOylation assays in COS7 (Fig. 4A) and 293T (data not shown) cells showed no change in Maf1 SUMOylation upon rapamycin treatment. These results indicate that inhibition of the mTOR pathway by rapamycin does not affect Maf1 SUMOylation at Lys-35.

FIGURE 4.

SUMOylation at Lys-35 and phosphorylation at Ser-75 are independent Maf1 modifications. A, Maf1 phosphorylation by mTOR kinase has no effect on Maf1 SUMOylation. COS7 cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing Maf1-HAWT and Myc-SUMO1ρ as indicated. Cells were treated with 100 nm rapamycin for 6 h. Cells treated with DMSO were used as a negative control. Cell lysates were then immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies. B, mutation at Ser-75 does not affect Maf1 SUMOylation at Lys-35. COS-7 cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing Myc-SUMO1ρ and Maf1-HAWT or Maf1HA mutants as indicated. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies. C, SUMOylation of Maf1 at Lys-35 does not affect phosphorylation at Ser-75. 293T cells were transfected with Maf1WT or Maf1K35R and Myc-SUMO1ρ expression vectors. Cell extracts were immunoblotted on a Phos-tag gel with HA antibodies.

Mutation of the serine 75 residue to alanine enhances Maf1-mediated repression of RNA pol III-dependent promoters (12, 18). To determine whether phosphorylation at Ser-75 affects SUMOylation of Maf1 at Lys-35, we examined whether Maf1 Ser-75 mutants could be SUMOylated. Both Maf1S75A and Maf1S75D were covalently modified by SUMO1 or SUMO2 (Fig. 4B). Additionally, expression of both the phospho mutant and the phospho mimic mutants was increased by SUMO. This indicates that Ser-75 phosphorylation does not affect covalent SUMOylation of Maf1 or the ability of increased cellular SUMOylation to induce Maf1 expression. To further determine whether SUMOylation affects the phosphorylation state of Maf1, we examined changes in the mobility of Maf1WT and Maf1K35R bands in the absence and presence of SUMO by phosphate affinity SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4C). Maf1K35R had a banding pattern similar to that of Maf1WT. Upon increased expression of SUMO, an additional faster migrating band was observed for both Maf1WT and Maf1K35R. Together, these results support the idea that SUMOylation of Maf1 at Lys-35 and phosphorylation at Ser-75 are independent events but that overall changes in cellular SUMOylation may change the phosphorylation of Maf1 at other sites within the protein.

SUMOylation Promotes the Ability of Maf1 to Repress Transcription and Suppress Colony Formation

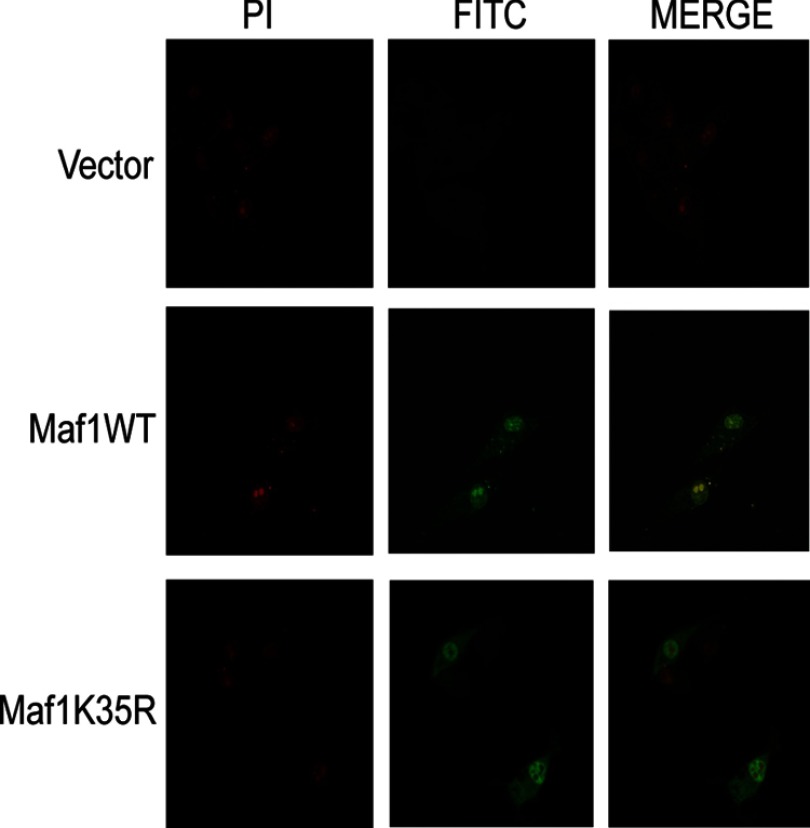

We investigated whether covalent SUMO modification at Lys-35 affects Maf1 subcellular localization (Fig. 5). Immunofluorescence staining of U87 cells transfected with either HA-tagged Maf1WT or HA-tagged Maf1K35R revealed that Maf1WT was predominantly nuclear with a fraction of Maf1 in the cytoplasm. Expression of Maf1K35R showed comparable nuclear and cytoplasmic staining to that of Maf1WT. These results indicate that covalent attachment of SUMO at Lys-35 does not affect the overall subcellular localization of Maf1.

FIGURE 5.

Covalent SUMO modification does not affect Maf1 localization. U87 cells were transiently transfected with either Maf1WT or Maf1K35R expression vectors. 24 h after transfection, immunofluorescence staining was carried out with HA antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. The nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (PI). Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the cells.

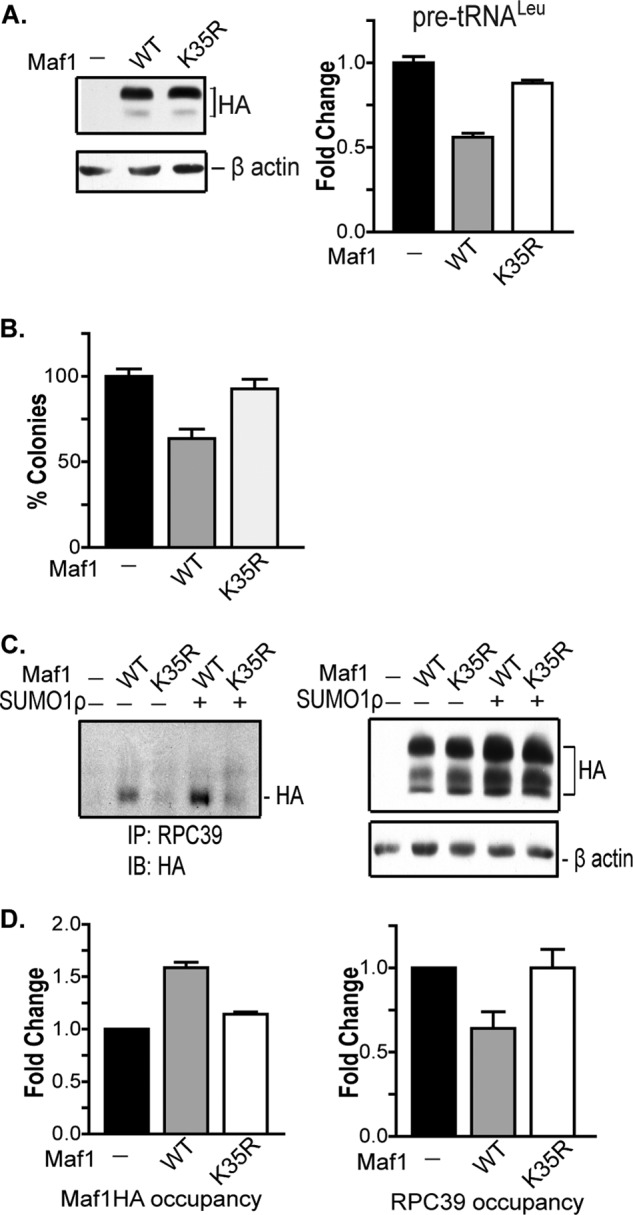

We further determined how SUMOylation at Lys-35 would affect Maf1 function. Maf1K35R was significantly impaired in its ability to repress pre-tRNALeu gene transcription when compared with Maf1WT (Fig. 6A). As previous results demonstrated that Maf1 suppresses anchorage-independent growth of U87 cells (6), we further examined the biological consequence of Maf1 SUMOylation on cell growth using a colony growth suppression assay. Although ectopic expression of Maf1WT resulted in a significant decrease in the number of colonies formed, Maf1K35R expression failed to significantly suppress colony formation (Fig. 6B). Thus, consistent with the SUMO-mediated modulation of these genes by Maf1, SUMO modification of Maf1 affects its growth-suppressive function.

FIGURE 6.

SUMO modification affects Maf1 function. A, SUMOylation of Maf1 at Lys-35 promotes transcription repression. U87 cells were transfected with Maf1WT and Maf1K35R expression vectors. qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using pre-tRNALeu and GAPDH primers. Gene expression was quantified using GAPDH as an internal control. Values represent means ± S.E. (n = 6). -Fold changes are statistically significant: analysis of variance, p < 0.0001. Protein lysates were immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies. B, SUMOylation of Maf1 promotes its growth suppression activity. U87 cells were transiently transfected with Maf1WT or Maf1K35R and puromycin-resistant expression vectors. Resistant colonies were selected for 3 weeks, stained with crystal violet, and counted. The number of colonies, converted to percentage of survival, is statistically significant: analysis of variance, p = 0.0006. Values represent means ± S.E. (n = 4). C, SUMOylation facilitates the interaction of Maf1 with RNA pol III. 293T cells were co-transfected with Maf1WT or Maf1K35R and Myc-SUMO1ρ expression vectors. Cells transfected with empty vector were used as a negative control. Left panel: lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with RPC39 antibody followed by immunoblot (IB) analysis with HA antibody. Right panel: cell extracts were immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies. D, SUMOylation at Lys-35 enhances its recruitment to tRNA gene promoters. U87 cells were transfected with HA-tagged Maf1WT or Maf1K35R expression vectors. Cells transfected with empty vector were used as a control. Chromatin was isolated and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to HA, RPC39, and IgG. DNA was then isolated, and quantitative PCR analysis was carried out using primers to the tRNALeu gene promoter. After normalizing to IgG, the vector control was set to 1, and -fold change was calculated. Values represent means ± S.E. (n = 3).

SUMOylation Affects Maf1 Interactions with RNA pol III and Its Recruitment to tRNA Genes

Although the mechanism by which Maf1 represses RNA pol III-mediated transcription is not well understood, initial structural studies demonstrated that Maf1 interacts directly with RNA pol III (3, 19, 20). Therefore, we examined whether SUMOylation affects the interaction between Maf1 and RNA pol III (Fig. 6C). Protein lysates from cells expressing either Maf1WT or Maf1K35R were either immunoblotted with HA and β-actin antibodies or immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the RNA pol III subunit, RPC39. Immunoblot analysis with HA antibodies revealed that Maf1WT associates with RNA pol III and that increased SUMO expression results in an increase in this association. However, Maf1K35R did not effectively interact with RNA pol III, even upon increased SUMO1 expression. Thus, covalent modification of Maf1 by SUMO at Lys-35 facilitates the association of Maf1 with RNA pol III.

To determine whether the recruitment of Maf1 and RNA pol III to tRNA gene promoters is dependent on Maf1 SUMOylation, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 6D). Maf1WT was recruited to the tRNALeu gene, resulting in diminished occupancy of RNA pol III. In contrast, Maf1K35R was impaired in its ability to occupy the tRNALeu gene, and no change in RNA pol III binding was observed. These results reveal that Maf1 SUMOylation promotes its recruitment to target promoters and that the interaction of Maf1 with RNA pol III facilitates the dissociation of RNA pol III and transcription repression.

DISCUSSION

Although SUMOylation has been shown to play an important role in regulating RNA pol II-dependent transcription, the potential role of SUMOylation on RNA pol I- or pol III-dependent gene expression has not been studied. We have uncovered a new role for SUMOylation in controlling the biosynthetic capacity of cells through its ability to negatively affect RNA pol III-dependent transcription. We have identified a key molecular event by which SUMO1 and SUMO2 exerts a negative affect on RNA pol III-dependent transcription through covalent modification of Maf1. Although the SUMOylation process may target other proteins to regulate this transcription process, the SUMOylation of Maf1 appears to play a critical role in repressing the transcription of these genes.

Our studies have uncovered a new mechanism by which mammalian Maf1 is regulated through covalent modification by SUMO. In yeast, Maf1 is regulated through phosphorylation by PKA and the TORC1-regulated Sch9 kinase (21, 22). Phosphorylation of Maf1 at these sites results in its inactivation by preventing its nuclear accumulation under non-stress conditions. Although these specific sites are not conserved in mammalian Maf1, analysis of a cluster of serine phosphosites on human Maf1, including Ser-75, revealed that they are phosphorylated by mTORC1 (12, 18), resulting in a diminished capacity to repress RNA pol III-dependent transcription. Mutation of these serine residues, however, does not appear to markedly alter the nuclear localization of Maf1 (11). Thus, the molecular mechanism by which phosphorylation of mammalian Maf1 impairs its function is not yet clear. Our results demonstrate that SUMO modification at Lys-35 and phosphorylation at Ser-75 are independent events. In addition, inhibition of mTOR has no affect on the ability of Maf1 to be SUMOylated. Thus, these initial results suggest that distinct pathways control mTOR-dependent phosphorylation and SUMOylation of Maf1.

Maf1 directly interacts with RNA pol III (3), and our results support the idea that SUMOylation of Maf1 facilitates this interaction. The Lys-35 residue in Maf1 is conserved from yeast to humans (3). According to crystal structure information of human Maf1 (19), Lys-35 is located at the beginning of a mobile loop region following a β-sheet β2, suggesting that SUMOylation at this site does not dramatically alter the overall conformation of Maf1. As the Lys-35 residue protrudes outward, SUMOylation at this site could provide a contact for the interaction of Maf1 with RNA pol III. Thus, the structure information is so far consistent with our experimental observation that SUMOylation of Maf1 is important for its interaction with RNA pol III.

Our results are consistent with the idea that there are at least two SUMO-dependent changes that control the amount and function of Maf1. The covalent attachment of SUMO to Maf1 Lys-35 alters Maf1 function but does not affect its expression. However, global changes in SUMOylation additionally affect the amount of Maf1 protein expression. Maf1 protein is increased by the overexpression of SUMO1 or SUMO2, whereas decreased expression of Ubc9 reduces the cellular amounts of Maf1 protein. These results suggest that the SUMOylation status of other cellular proteins may regulate Maf1 expression, independent of Maf1 Lys-35 SUMOylation. This change in Maf1 protein expression is likely to occur post-transcriptionally as Maf1 mRNA levels are not affected by changes in Ubc9 expression. In addition, these SUMO-dependent changes in Maf1 expression are independent of SENP1 as altered expression of this deSUMOylase does not affect the amount of cellular Maf1 protein. Together, our results support the idea that SUMOylation regulates both Maf1 function and protein expression and that these processes are independent of each other. Further studies are needed to define the SUMOylation events that control Maf1 expression.

Emerging evidence supports the idea that SUMOylation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of various human diseases, including cancer (23). However, the molecular events mediated by the SUMOylation pathway that drive oncogenesis are still poorly understood. Ubc9 is overexpressed in a number of human cancers (24), suggesting that an overall increase in SUMOylation drives tumorigenesis. However, this is contrary to our observations that down-regulation of Ubc9 promotes induction of RNA pol III-dependent transcription, a process that is known to be required for oncogenic transformation (2). Thus, it is likely that the specificity of the SUMOylation events that drive tumor development is dictated by the expression and activity of the SUMO E3 ligases and the SENP proteases. Several SENPs, including SENP1 and SENP3, are overexpressed in the early stages of various carcinomas (25, 26), indicating that select deSUMOylation events mediated by specific SENP proteins drives cancer development. Consistent with this idea, we find that SENP1 controls Maf1 SUMOylation. SENP1 is overexpressed as an early event in human prostate cancer, and its expression correlates with tumor aggressiveness, bone metastasis, and recurrence (26). Given the idea that Maf1 targets genes that promote oncogenic transformation and that altered Maf1 expression impacts the growth and transformation state of cells, it is likely that Maf1 function is compromised in those cancers that aberrantly express SENP1 or other SUMOylation components that affect Maf1 expression or function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Abraham Kaslow for technical assistance and Dr. David Ann for the SUMO expression plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA108614 (to D. L. J.).

- pol

- RNA polymerase

- TBP

- TATA-binding protein

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifier

- SENP

- sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Johnson D. L., Johnson S. A. (2008) Cell biology. RNA metabolism and oncogenesis. Science 320, 461–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson S. A., Dubeau L., Johnson D. L. (2008) Enhanced RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription is required for oncogenic transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19184–19191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pluta K., Lefebvre O., Martin N. C., Smagowicz W. J., Stanford D. R., Ellis S. R., Hopper A. K., Sentenac A., Boguta M. (2001) Maf1p, a negative effector of RNA polymerase III in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 5031–5040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Upadhya R., Lee J., Willis I. (2002) Maf1 is an essential mediator of diverse signals that repress RNA polymerase III transcription. Mol. Cell 10, 1489–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boguta M. (2013) Maf1, a general negative regulator of RNA polymerase III in yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 376–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson S. S., Zhang C., Fromm J., Willis I. M., Johnson D. L. (2007) Mammalian Maf1 is a negative regulator of transcription by all three nuclear RNA polymerases. Mol. Cell 26, 367–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhong S., Fromm J., Johnson D. L. (2007) TBP is differentially regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) and JNK2 through Elk-1, controlling c-Jun expression and cell proliferation. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 54–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson S. A., Dubeau L., Kawalek M., Dervan A., Schönthal A. H., Dang C. V., Johnson D. L. (2003) Increased expression of TATA-binding protein, the central transcription factor, can contribute to oncogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3043–3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hay R. (2005) SUMO: a history of modification. Mol. Cell 18, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Müller S., Ledl A., Schmidt D. (2004) SUMO: a regulator of gene expression and genome integrity. Oncogene 23, 1998–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kantidakis T., Ramsbottom B. A., Birch J. L., Dowding S. N., White R. J. (2010) mTOR associates with TFIIIC, is found at tRNA and 5S rRNA genes, and targets their repressor Maf1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11823–11828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michels A. A., Robitaille A. M., Buczynski-Ruchonnet D., Hodroj W., Reina J. H., Hall M. N., Hernandez N. (2010) mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and regulates human MAF1. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 3749–3757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bawa-Khalfe T., Yeh E. T. (2010) SUMO losing balance: SUMO proteases disrupt SUMO homeostasis to facilitate cancer development and progression. Genes Cancer 1, 748–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin X., Liang M., Liang Y. Y., Brunicardi F. C., Feng X. H. (2003) SUMO-1/Ubc9 promotes nuclear accumulation and metabolic stability of tumor suppressor Smad4. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31043–31048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li X., Luo Y., Yu L., Lin Y., Luo D., Zhang H., He Y., Kim Y. O., Kim Y., Tang S., Min W. (2008) SENP1 mediates TNF-induced desumoylation and cytoplasmic translocation of HIPK1 to enhance ASK1-dependent apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 15, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fromm J. A., Johnson S. A., Johnson D. L. (2008) Epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR1) and its variant EGFRvIII regulate TATA-binding protein expression through distinct pathways. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 6483–6495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gridasova A. A., Henry R. W. (2005) The p53 tumor suppressor protein represses human snRNA gene transcription by RNA polymerases II and III independently of sequence-specific DNA binding. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3247–3260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shor B., Wu J., Shakey Q., Toral-Barza L., Shi C., Follettie M., Yu K. (2010) Requirement of the mTOR kinase for the regulation of Maf1 phosphorylation and control of RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15380–15392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vannini A., Ringel R., Kusser A. G., Berninghausen O., Kassavetis G. A., Cramer P. (2010) Molecular basis of RNA polymerase III transcription repression by Maf1. Cell 143, 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Desai N., Lee J., Upadhya R., Chu Y., Moir R. D., Willis I. M. (2005) Two steps in Maf1-dependent repression of transcription by RNA polymerase III. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6455–6462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moir R. D., Lee J., Haeusler R. A., Desai N., Engelke D. R., Willis I. M. (2006) Protein kinase A regulates RNA polymerase III transcription through the nuclear localization of Maf1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15044–15049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee J., Moir R. D., Willis I. M. (2009) Regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription involves SCH9-dependent and SCH9-independent branches of the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12604–12608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sarge K. D., Park-Sarge O. K. (2011) SUMO and its role in human diseases. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 288, 167–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDoniels-Silvers A. L., Nimri C. F., Stoner G. D., Lubet R. A., You M. (2002) Differential gene expression in human lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 1127–1138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Han Y., Huang C., Sun X., Xiang B., Wang M., Yeh E. T., Chen Y., Li H., Shi G., Cang H., Sun Y., Wang J., Wang W., Gao F., Yi J. (2010) SENP3-mediated de-conjugation of SUMO2/3 from promyelocytic leukemia is correlated with accelerated cell proliferation under mild oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12906–12915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Q., Xia N., Li T., Xu Y., Zou Y., Zuo Y., Fan Q., Bawa-Khalfe T., Yeh E. T., Cheng J. (2013) SUMO-specific protease 1 promotes prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene 32, 2493–2498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]