Abstract

Inositol phosphatases are important regulators of cell signaling, polarity, and vesicular trafficking. Mutations in OCRL, an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, result in Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe, an X-linked recessive disorder that presents with congenital cataracts, glaucoma, renal dysfunction and mental retardation. INPP5B is a paralog of OCRL and shares similar structural domains. The roles of OCRL and INPP5B in the development of cataracts and glaucoma are not understood. Using ocular tissues, this study finds low levels of INPP5B present in human trabecular meshwork but high levels in murine trabecular meshwork. In contrast, OCRL is localized in the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells in both human and murine eyes. In cultured human retinal pigmented epithelial cells, INPP5B was observed in the primary cilia. A functional role for INPP5B is revealed by defects in cilia formation in cells with silenced expression of INPP5B. This is further supported by the defective cilia formation in zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicles and in cilia-dependent melanosome transport assays in inpp5b morphants. Taken together, this study indicates that OCRL and INPP5B are differentially expressed in the human and murine eyes, and play compensatory roles in cilia development.

Introduction

Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe (MIM #309000) is an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by the presence of congenital cataracts, glaucoma, mental retardation, and renal dysfunction [1], [2], [3]. Lowe syndrome results from mutations in OCRL, a type II inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase [2]. Patients with Lowe syndrome typically present with bilateral congenital discoid cataracts, which may be caused by disorganization of embryonic lens epithelium [4], [5]. Glaucoma is present in approximately 47% (44 of 93) of Lowe syndrome patients [4]. When observed at birth, glaucoma development in the Lowe syndrome patients represent a form of trabeculodysgenesis, which is the abnormal development of the trabecular meshwork that regulates aqueous humor outflow from the eye [4]. Produced by the nonpigmented layer of epithelial cells (NPCE) in the ciliary body, the major route of aqueous humor drainage is via the trabecular meshwork and then into the Schlemm’s canal, a monolayer of endothelial cells, where it finally drains out of the eye by joining the venous blood vessels [6]. Over 208 mutations in OCRL have been described with a wide range of phenotypes that involve multiple organ systems [7]. However, very little is known how defects in OCRL results in cellular dysfunction that underlies cataracts formation and the defective flow of aqueous humor that leads to congenital glaucoma.

Type II inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (INPP5B), a paralog of OCRL, is also an important regulator of intracellular phosphoinositide levels [8]. INPP5B and OCRL share 45% sequence identity, similar domain architecture, and substrate specificity [9], [10], [11], [12]. Both INPP5B and OCRL are recruited to the membrane of endosomes and plasma membrane, where OCRL has been shown to be important in clathrin-mediated trafficking [9], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Although Ocrl knockout mice do not display the typical symptoms of Lowe syndrome, Inpp5b knockout mice exhibit male sterility, which has limited functional studies to distinguish their roles in Lowes syndrome [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. The embryonic lethality of Ocrl−/−:Inpp5b−/− double knockout mice suggests that these genes have overlapping functions [19].

Phosphoinositides and the phosphatases that regulate their metabolism have key roles in the development of the primary cilia [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. A subcellular organelle present in almost all post-mitotic cells, the primary cilium is formed by a microtubule-based axoneme and a basal body, which is the nucleating center for the axoneme [30], [31]. Disruptions in the primary cilium can result in a range of clinical abnormalities that collectively are known as ciliopathies [32], [33]. A Type IV inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, INPP5E, has been localized to the cilium and mutations in INPP5E have been found in Joubert syndrome, which presents with retinitis pigmentosa, kidney cysts, and mental developmental delays [26], [27], [34]. Recently several groups have found OCRL in the primary cilia, supporting the role of inositol 5-phosphatases in cilia formation [35], [36], [37].

This study analyzes the intracellular localization and interactions of OCRL and INPP5B in ocular tissues responsible for cataract and glaucoma development. Based on genetic studies, the differential expression of OCRL and INPP5B are proposed to underlie disease pathogenesis of the ocular phenotypes. Further, given the roles of OCRL and INPP5E in the primary cilium, INPP5B was investigated for roles in the primary cilium. INPP5B indeed localizes to the cilia but unlike OCRL, this requires an intact C-terminal CAAX prenylation domain. Knockdown of inpp5b results in zebrafish morphants with reduced cilia length in Kupffer’s vesicle (KV) and other cilia-related phenotypes. Together, INPP5B is found to have an overlapping function with OCRL in cilia development.

Methods and Materials

Reagents

Anti-OCRL antibodies have been previously described [35]. Anti-INPP5B antibody was purchased from Proteintech (Immunogen: 1–309 amino acid of human INPP5B)(Chicago, IL). Antibodies against gamma-tubulin, and acetylated alpha-tubulin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Secondary antibodies AlexaFluor 488 and 546 -conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1∶1000), Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1∶500), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc (West Grove, PA). IRDye goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit (680 and 800) were obtained from Li-cor Bioscience (Lincoln, NB).

DNA Constructs

FLAG-INPP5B, FLAG-Inpp5b and lentiviral GFP-Inpp5b were generated using Creator (Clontech) based vectors as described [38]. FLAG-INPP5B-delta-CAAX, FLAG-Inpp5b-delta-CAAX and lentiviral GFP-Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mutant were generated using QuikChangeII kit from Stratagene (Santa Clara, CA).

Human Ocular Specimens and Animal Tissue

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement on the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. All procedures in rats were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Indiana University (Study number #0000003163). Zebrafish studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Indiana University (Study number #3843). Human eyes specimens were obtained with approval of Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Boards (IRB-HSBS) of University of Michigan (HUM00034652) and was previously published [35]. Mice mOcrl−/−:mInpp5b−/−:hINPP5B +/+ (ocular samples were generous gifts of Dr. R. Nussbaum, University of California, SF, CA) were previously described [21].

Cell Culture and Transfection

hTERT-RPE1 (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in DMEM/F-12+GlutaMAX (GIBCO) with 10% FCS, penicillin–streptomycin at 37 C in 5% CO2. Primary human trabecular meshwork (HTM) cells were generous gifts of Dr. Juanita Dortch-Carnes (Morehouse school of Medicine, Atlanta, GA) [39]. Normal human fibroblast (NHF) is a gift of Dr. Dan Spandau (Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN) as previously described [35]. Lowe 1676 and Lowe 3265 patient fibroblasts (Coriell Institute) have markedly decreased OCRL protein levels and were previously characterized [35]. Transfections were performed using Polyethylenimine according to previous published protocol [40].

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry was performed by obtaining ten micrometer sections from formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue, stained with H&E as previously described [35]. Immunofluorescence slides were treated with paraformaldehyde (PFA) for fixation for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT) followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100, then blocked with Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/0.5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)/10% Normal Goat Serum (NGS) for 30 minutes at RT. Cover slips were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, secondary antibodies for 45 minutes at RT, and mounted in ProLong Antifade reagent (Invitrogen). The hTERT-RPE1 cells were synchronized by serum starvation according to previous protocols [41]. To evaluate cilia length, cells were grown to confluence for 48 hours followed by serum deprivation, then fixed with 4% PFA and cilia growth was analyzed by immunostaining with acetylated α-tubulin from z-stacks (0.56 micron step size) taken with LEICA SP6 confocal microscope or Zeiss LSM-700 confocal microscope. Ciliary length was measured with NIH Image J software and statistical analysis was performed with SAS.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10%–12% gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad). Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in PBS. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in concentrations as described above [35]. Odyssey Imaging system (Li-Cor Bioscience) was used to analyze the immunoblots.

Knockdown of INPP5B in Cells

INPP5B and control knockdown shRNA lentivirus was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Lentiviral particles were transduced into hTERT-RPE1 cells using standard protocols. Knockdown of INPP5B was verified by immunoblotting as described [42].

Zebrafish Immunohistochemistry and KV Cilia Measurements

Zebrafish (wildtype strain: AB Tubingen) were raised and maintained at the Laboratory Animal Resource Center of Indiana University. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH. The protocol was approved by the Indiana University Animal Care and Use committee (number 3843). All surgery was performed under paracaine anesthesia. Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% sucrose in PBS. Embryos were dechorionated and washed with PBST for 6–8 times 10 min each. After blocking them for 2–4 hr with 10% NGS and 0.5% BSA, immunostaining was performed with 1∶200 anti-acetylated tubulin monoclonal antibody and 1∶500 AlexaFluor 546 donkey anti-mouse conjugate separately at 4°C overnight. KV cilia measurements were performed as described [43]. Cresyl violet staining were performed as described [42].

Morpholino Antisense Oligonucleotides Knockdown and mRNA Rescue in Zebrafish

Antisense MOs were designed and purchased from Gene Tools, Inc. (Philo, OR). Two morpholinos were generated; inpp5b translational blocking MO (inpp5b MO: sequence CTCCTGAAACCCGCCATCAGCGTTC), mismatch (control MO: sequence ATGCGAAATCAAGGTTCGATCATCA), and p53 (p53 MO: sequence GCGCCATTGCTTTGCAAGAATTG) morpholino served as a negative control. Morpholinos stocks were dissolved at 1 mM in water: 2 or 4 nl of injection solution (0.25% phenol red) containing 125–500 mM morpholino was injected into fertilized eggs at the one- to two-cell stage using a pressure injector (Pressure System IIe, Toohey Company, Fairfield, NJ). Synthetic mRNA was prepared from linearized human DNA with Ambion mMessage mMachine high-yield Capped RNA transcription kit, purified with phenol-chloroform, and mRNA was coinjected for rescue experiments as previously described [35].

Retrograde Melanosome Transport Assay

Melanosome transport assay was performed as described [42]. Briefly, zebrafish 5 dpf larvae were exposed to epinephrine (50 mg/ml, Sigma) at the final concentration of 2 mg/ml in a dark room, and melanosome retractions were observed under the brightfield microscope Leica DFC310 FX. The end of melanosome transport was marked when all melanosomes in the head were perinuclear.

Results

Localization of Inositol Phosphates to the Cilia in Ocular Tissues

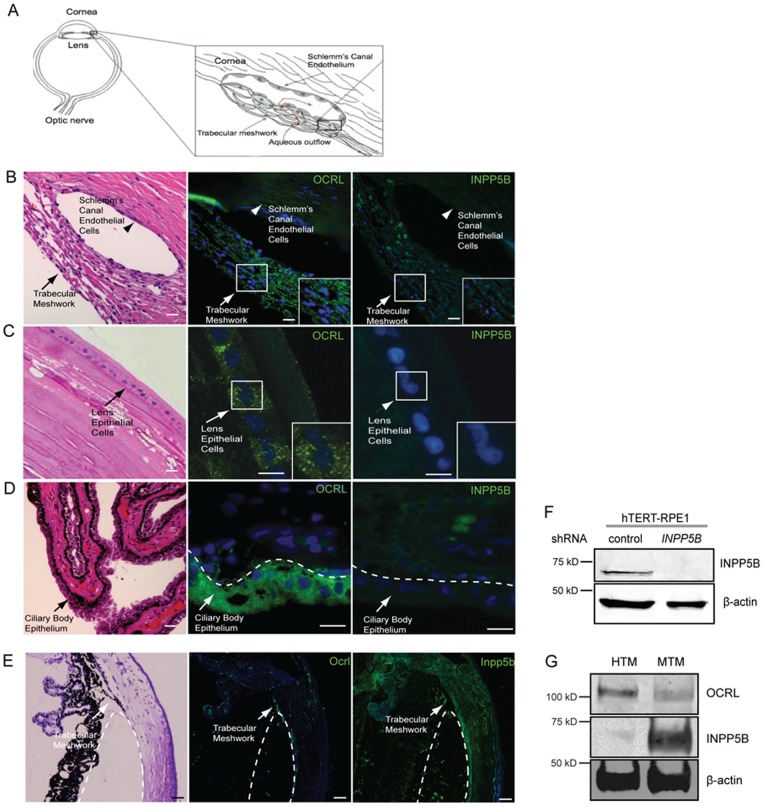

OCRL mutations have been found in Lowe syndrome, which usually presents with bilateral congenital cataracts and glaucoma [4]; however, the pathogenesis of these ocular phenotypes is not known. In the anterior segment of the eye, the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells regulate aqueous outflow and are often affected in glaucoma patients (Fig. 1A). We hypothesized that OCRL is expressed in human tissues that are responsible for cataract and glaucoma development. To test this hypothesis, we examined human eyes previously enucleated for solitary choroidal melanoma that retained normal anterior and posterior segments. These sections were stained by H&E and immunohistochemistry was carried out with a previously characterized affinity-purified anti-OCRL antibody [35]. Indeed, OCRL was observed in punctate vesicles in the trabecular meshwork and lens epithelial cells; in addition, low level of protein expression was also detected in the Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, staining of eye sections using an anti-INPP5B antibody showed nearly undetectable signal in human trabecular meshwork as well the Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells.

Figure 1. Localization of OCRL and INPP5B in human ocular tissue.

(A) Diagram of trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells (aqueous flow, red; trabecular meshwork, arrow; Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells, arrowhead). (B) Human eye sectioned and stained by H&E or immunofluorescence with anti-OCRL (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Staining of trabecular meshwork cells in vesicular pattern (insert, arrow) and Schlemm’s canal (arrowhead). Scale bar 10 micron. (C) Lens epithelial cells (arrow) stained with H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. (D) Ciliary body epithelial (arrowhead) cells stained with H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. (E) Mouse eye sectioned and stained with H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Staining of trabecular meshwork cells in vesicular pattern (dash line indicates border of trabecular meshwork). Scale bar 10 micron. (F) Immunoblot of INPP5B expression in 30 microgram lysates of hTERT-RPE1 shRNA knockdown cells compared to beta-actin. (G) Immunoblot analysis of 40 microgram lysates of human and mouse trabecular meshwork with anti-OCRL, anti-INPP5B and anti-beta-actin antibodies.

The epithelial cells of the lens are a monolayer of epithelium with the basement membrane directed outwardly towards the anterior chamber. Similarly to the trabecular meshwork staining, OCRL is detected in a vesicular pattern but not INPP5B (Fig. 1C). The ciliary body epithelium, which is composed of outer pigmented and inner non-pigmented epithelium, was also examined for inositol phosphatase distribution. The non-pigmented epithelium (NPCE) is responsible for aqueous secretion and is the target for many anti-glaucoma medications. OCRL was detected in human ciliary body epithelium primarily in the outer pigmented epithelial cells; however, INPP5B protein was not detected (Fig. 1D). In the posterior segment of the eye, we found INPP5B immunoreactivity in the outer segment of the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE); the pattern of localization corresponds to the outer photoreceptor segments (Fig. S1A-B in File S1). Similar immunohistochemical results for INPP5B and OCRL were obtained from rat eyes (data not shown).

OCRL and INPP5B are paralogous genes with overlapping enzymatic functions [19]. Although the loss of OCRL in humans results in severe multi-organ phenotypes, inactivation of Ocrl in mice does not phenocopy human disease. This may be due to redundancy of Inpp5b, which is supported by the early embryonic lethality of loss of both Ocrl and Inpp5b. Thus we compared the expression of Ocrl and Inpp5b in murine trabecular meshworks (MTM). The trabecular meshwork in murine eyes stained similarly for both OCRL and INPP5B (Fig. 1E). Using a purified antibody against INPP5B, we show the specificity by immunoblotting using lysates of hTERT-RPE1 knockdown of INPP5B (Fig. 1F). However, a comparison of their expression patterns in human trabecular meshwork (HTM) reveals that the protein level for OCRL was higher in HTM cells while INPP5B was relatively in MTM cells (Fig. 1G). Taken together, OCRL and INPP5B are differentially expressed in the ocular tissues involved in glaucoma and cataract development.

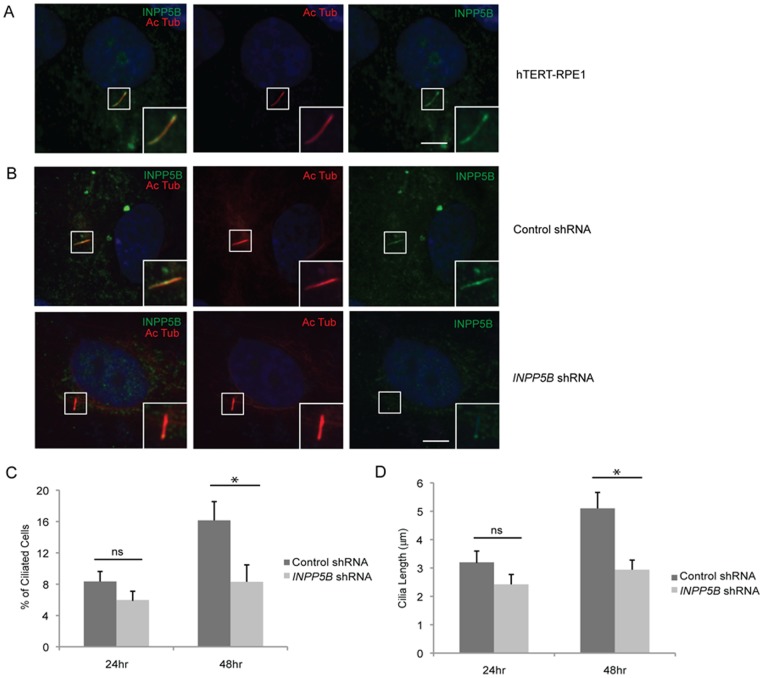

INPP5B Localization to the Primary Cilia

Because of the compensatory function of Ocrl and Inpp5b in mice, we hypothesized that INPP5B is also a ciliary protein. To address this possibility, we used hTERT-RPE1 cells, which is a well-described ciliated epithelial cell line [44]. Ciliogenesis was induced in hTERT-RPE1 cells by serum-starvation for 24 to 48 hr and the presence of INPP5B in the primary cilia was then examined with acetylated alpha-tubulin immunostaining. This showed that INPP5B localizes distinctly along the primary cilia (Fig. 2A). The immunostaining was absent in cells treated with shRNA INPP5B via a lentiviral vector, which resulted in an approximately 90% decrease in INPP5B expression as compared to controls (Fig. 2B–C). INPP5B was also detected with gamma-tubulin, a basal body marker (Fig. S2 in File S1).

Figure 2. INPP5B localizes to primary cilia.

(A) hTERT-RPE1 cells were starved for 48 hr, and analyzed by immunostaining with anti-INPP5B antibody and anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin antibody. Scale bar 5 micron. (B) Control and INPP5B shRNA hTERT-RPE1 cells were starved for 48 hr, and analyzed by immunostaining with anti-INPP5B antibody and anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin antibody. Scale bar 5 micron. (C-D) Control and INPP5B shRNA hTERT-RPE1 cells were starved for 24 hr or 48 hr, and analyzed by immunostaining with anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin antibody. Percent ciliated cells (C) and the length of cilia (D) were quantified. (n = the number of cilia n >100 cilia, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 2.1E-08 in D, * p = 3.1 E-09 in E; ns, not statistically significant).

Consequently, a role of INPP5B in cilia development was explored. INPP5B knockdown (KD) resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of ciliated cells in comparison to control KD cells. Approximately 21% and 50% less ciliated cells were observed for INPP5B KD at 24 hour and 48 hour, respectively (8.2%±2% at 24 hour control KD vs 6.5%±1.5% in INPP5B KD cells, p = 0.04; 16%±2% at 48 hour control KD vs 8%±2% in INPP5B KD cells, p = 2.1E-08) (Fig. 2D). While decreased levels of INPP5B affected ciliation, we also assessed the cilia length in cells serum-starved at 24 and 48 hr. We found that the lengths of the cilia in INPP5B KD cells were significantly reduced as compared to control KD cells. After serum-starvation for 24 hr, hTERT-RPE1 control and INPP5B KD cells showed the cilia length to be 25% less than control cells (3.2±0.4 micron in control KD vs 2.4±0.3 micron in INPP5B KD cells, p = 0.1). About 45% less cells with INPP5B knockdown developed cilia when compared to controls cells after 48 hours of serum-starvation (5.1±0.6 micron in control KD vs 2.8±0.3 micron in INPP5B KD cells, p = 3.12E-09) (Fig. 2E). Therefore, INPP5B is important in development and regulation of primary cilia.

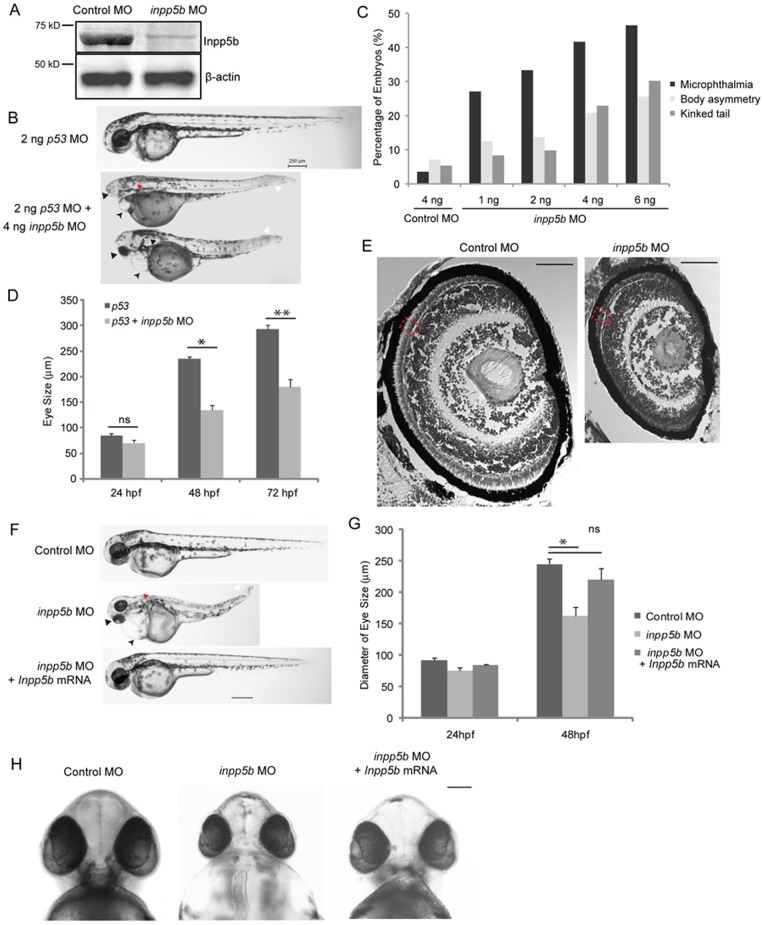

Knockdown of Zebrafish INPP5B Results in Cilia Defects

To further determine the functional significance of INPP5B expression in cilia development, morpholino targeting inpp5b expression in zebrafish was employed. The degree of homolog between zebrafish and human INPP5B is approximately 61.0% identity and 76.0% similarity. For this purpose, an antisense oligonucleotide morpholino and a 5-base-pair mismatched control MO were designed and tested. In zebrafish, a single copy of inpp5b is present, which was conveniently targeted using antisense morpholinos. As shown in Figure 3A, inpp5b morpholino-injected embryos specifically decreased Inpp5b protein expression as compared to beta-actin. Expression of inpp5b was verified by immunoblot analysis to demonstrate the specificity of anti-INPP5B antibody. At the 48 hpf stage, inpp5b morphants exhibited dose-dependent microphthalmia, body axis asymmetry, and kinked tail; an approximately 70% of morphants exhibited microphthalmia, which were observed over multiple independent sets of experiments (Fig. 3B–C). To verify that the phenotypes are specific to inpp5b knockdown, p53 MO were injected into zebrafish embryos. This showed that p53 MO alone did not result in decreased eye size, generalized edema, or body axis asymmetry in zebrafish, but these phenotypes appeared in the embryos when co-injected with inpp5b MO and p53 MO (Fig. 3B). These differences in eye size were statistically significant at 48 hpf between p53 morphants and p53 plus inpp5b morphants (236±3.5 micron vs 135±10 micron, p = 4.98E-07) (Fig. 3D). The significant difference in eye size was also found at 72 hpf between p53 morphants and p53 plus inpp5b morphants (293±9 micron vs 180±12 micron, p = 2.1E-10) (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Inpp5b morpholino affects multiple organ development in zebrafish.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of 40 microgram of total lysates of zebrafish embryo injected with control MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) at 48 hpf with anti-INPP5B and anti-beta-actin antibodies. (B) Zebrafish embryos were injected with p53 MO (2 ng) or p53 MO (2 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng). Representative phenotypes of microphthalmia (black arrowhead), pericardial edema (small arrow), body axis asymmetry, kinked tail (white arrow), pronephric cyst formation (red arrow), and hypopigmentation were observed at 48 hpf. Scale bar 250 micron. (C) Dose-dependent effect of morpholinos in zebrafish. Control or inpp5b MO at indicated doses was injected into zebrafish embryos, and phenotypes of microphthalmia, kinked tail, and body asymmetry were quantified at 48 hpf (ANOVA, F = 92, p = 3.6E-10), kinked tail (ANOVA, F = 3.6, p = 0.08), and body asymmetry (ANOVA, F = 5.2, p = 0.04). (N = the number of injected embryos N >50). (D) Quantification of eye size of morphants at 24 hpf, 48 hpf and 72 hpf. The eye size was determined by the longest diameters in dorsal view. (N >40 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 4.98E-07 ** p = 2.1E-10, ns, not statistically significant). (E) Cresyl violet staining of ocular sections of zebrafish larvae (5 dpf) injected with control MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng). Scale bar 30 micron. (F) Zebrafish embryos were injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (Inpp5b mRNA, 500 pg). Representative phenotypes of microphthalmia (arrowhead), pericardial edema (arrow), body axis asymmetry, kinked tail (white arrow), pronephric cyst formation (red arrow), and hypopigmentation were observed at 48 hpf. Scale bar 250 micron. (G) Quantification of eye size of zebrafish morphants at 24 hpf and 48 hpf. (N >40 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 4.5E-05). (H) The ventral sides of embryos were injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 pg). Scale bar 100 micron.

Detailed analysis of these ocular phenotypes found the inpp5b morphants developed dystrophic retina and thinner RPE versus control (Fig. 3E). The phenotypes of edema, body asymmetry, and kinked tail in inpp5b morphants are characteristics of functional defects of cilia, and can be partly rescued by co-injection of murine Inpp5b (Inpp5b) WT mRNA with inpp5b MO (Fig. 3F–H). The eye size of morphants at 48 hpf co-injected with Inpp5b WT mRNA was 220±18 micron, compared with the morphants injected with Inpp5b MO (162±15 micron) and control MO (245±7.9 micron) (Fig. 3G).

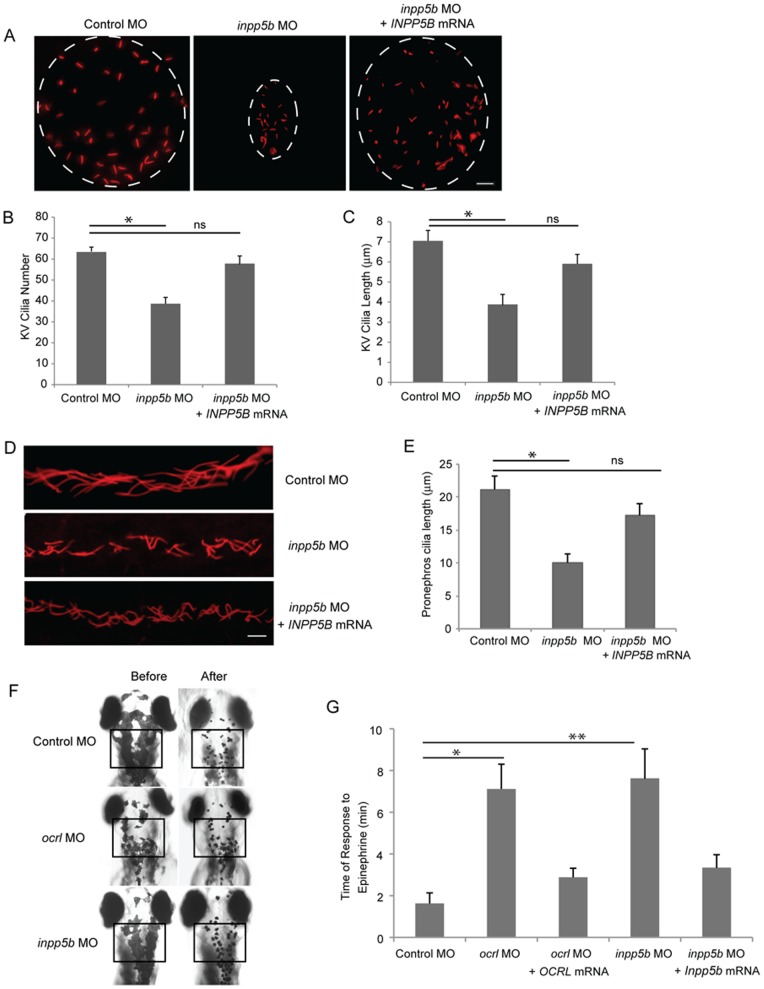

To evaluate whether Inpp5b is necessary for cilia development, we examined the Kupffer’s vesicle (KV) and pronephros duct of young zebrafish larvae. The KV is a ciliated, fluid-containing structure in the zebrafish, orthologous to the mouse embryonic node; it regulates left-right body axis and organ development through directional cilia rotation [45], [46]. KV was examined by immunohistochemistry with anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin to stain the cilia at the 6-somite stage (Fig. S3A in File S1). Compared with control MO-injected embryos, an approximate 50% reduction in the number of cilia in the KV of inpp5b morphants (64±2 vs 36±3 cilia, p = 3.41E-3) was detected (Fig. S3B in File S1). In addition, the average lengths of cilia within the KV were found to be shorter in the inpp5b morphants than controls embryos (4.3±0.5 micron vs 6.5±0.5 micron, p = 1.89E-23) (Fig. S3C in File S1). Cilia quantity (56±4) and lengths (6.2±0.5 micron) in the KV were rescued after co-injection with Inpp5b WT mRNA. Immunostaining of pronephric duct cilia with anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin at the 24 hpf stage was also carried out. Confocal images of individual cilium, with distinct base and ends (N >200 cilia), were outlined and the calculated length recorded. As compared to control MO-injected embryos, there was an approximately 50% shortening of cilia length in inpp5b morphants vs control embryos (9.5±1.8 micron vs 20±2.1 micron,p = 5.45E-18), and cilia length could be restored (17±1.9 micron) by co-injection with Inpp5b WT mRNA (Fig. S3D–E in File S1). Inpp5b is therefore concluded to exhibit an important role in cilia development and function during zebrafish embryogenesis. In zebrafish embryos co-injected with Inpp5b MO and human INPP5B WT mRNA, a reversal of ciliary phenotype was observed in KV cilia (Fig. 4A–C) and pronephric duct cilia (Fig. 4D–E). Compared with control MO-injected embryos, cilia number of KV return to 59±4 and average cilia length return to 5.7±0.6 micron. The pronephric cilia return to 17±2 micron.

Figure 4. Defects of cilia formation in Inpp5b zebrafish morphants.

(A) INPP5B WT mRNA rescue the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated α-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (B–C) Quantification of number (B) and length (C) of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng). (N >20 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 3.4E-03 in B and * p = 1.9E-23 in C). (D) INPP5B WT mRNA rescue of inpp5b pronephric cilia formation. Representative image of pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf stage, injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng), immunostaining with acetylated α-tubulin (red). Scale bar 10 micron. (E) Pronephric cilia length of control and inpp5b MO. Pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng) at 24 hpf stage were analyzed by immunostaining with acetylated alpha-tubulin and cilia length was measured. (N >200 cilia; three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 5.45E-18). (F) Ocrl and Inpp5b morphants showed slowed retrograde melanosome transport. Representative photos are shown for the melanosomes in Ocrl and Inpp5b morphants before and after treatment with epinephrine in 5 dpf embryos (box, region of pigment evaluation). (G) Quantification of the response time for epinephrine treatments in the control MO (2 ng), ocrl MO (2 ng), ocrl MO (2 ng) and OCRL WT mRNA (500 pg), inpp5b MO (2 ng), and inpp5b MO (2 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 pg) embryos (N >30 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 4.6E-50, ** p = 2.3E-43).

Interestingly, we observed a decreased pigmentation in the ocrl and inpp5b morphants (Fig. 4F). These findings were consistent with our previous studies [42] with the inpp5e morphants suggesting that the ocrl and inpp5b morphant zebrafish may also have defects in melanosome transport. To measure melanosome transport, we determined the rates of epinephrine-induced melanosome retraction in the zebrafish larvae. When 5 dpf embryos were exposed to epinephrine, melanosomes contracted rapidly and the endpoint was marked by perinuclear accumulation of melanosomes [47]. Pigment accumulation of ocrl morphants (7.4±0.9 min) and inpp5b morphants (7.7±1.0 min) was 3 times longer than control morphants (1.8±0.4 min) (Fig. 4G). Importantly, the delayed retraction could be rescued by co-injecting either OCRL mRNA or Inpp5b mRNA (Fig. 4G).

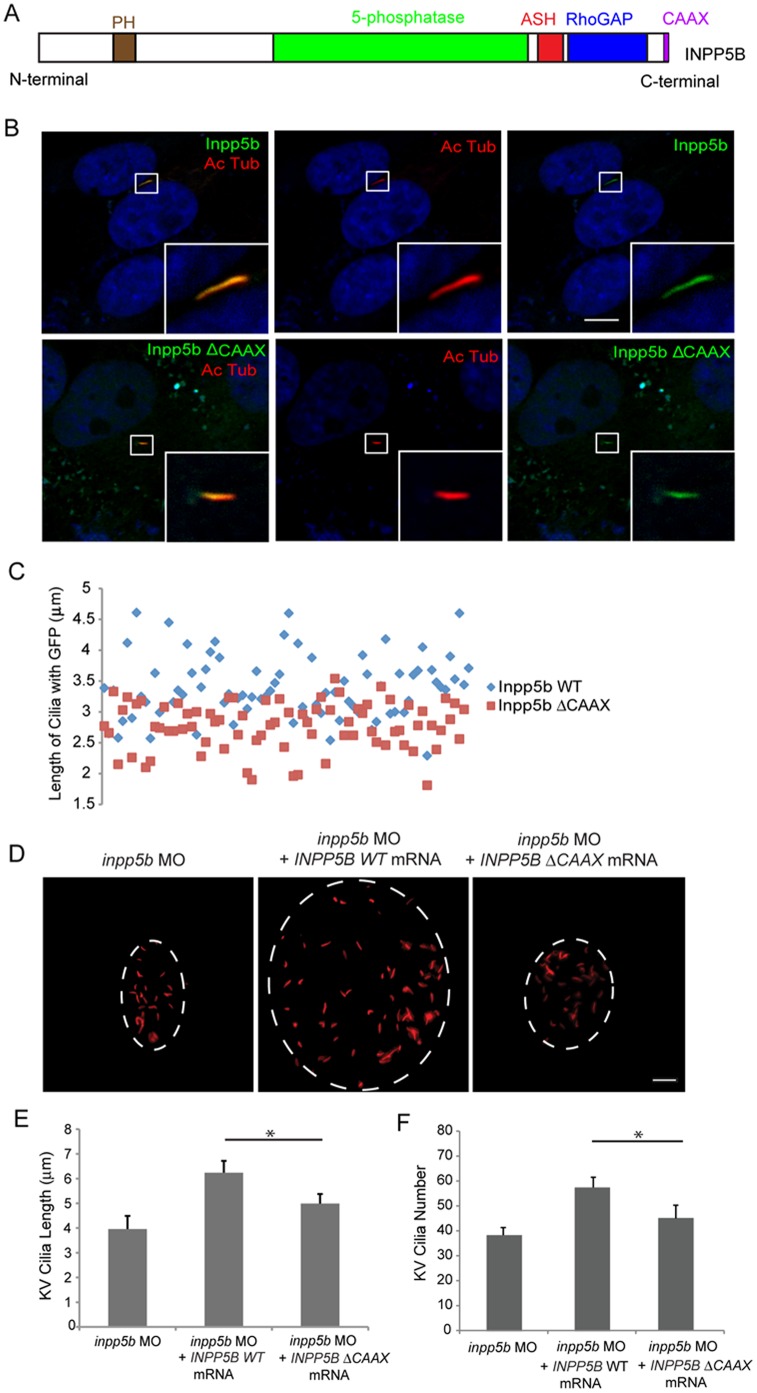

CAAX Domain of INPP5B Mediates Ciliary Localization

Inositol phosphatase INPP5E contains a prenylation CAAX motif, which was found to play a role in MORM syndrome (a ciliopathy) [27]. A premature stop codon in INPP5E affects ciliary localization but not its enzymatic activity. For this purpose, a CAAX deletion mutant of Inpp5b was assayed for its ability to be recruited to the cilia (Fig. 5A). In hTERT-RPE1 cells transduced with GFP-tagged lentivirus for either Inpp5b WT or Inpp5b-delta-CAAX, the localization of this protein by immunofluorescence was visualized (Fig. 5B). The expression of Inpp5b or Inpp5b-delta-CAAX was verified by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). In 48 hr serum-starved hTERT-RPE1 cells expressing either Inpp5b or Inpp5b-delta-CAAX, the loss of the CAAX motif significantly abolished the ciliary recruitment of INPP5B. In hTERT-RPE1 cells transduced with either Inpp5b or Inpp5b-delta-CAAX lentivirus, the length of GFP-positive cilia was assessed and a significant difference was noted (3.4±0.4 micron vs 2.8±0.3 micron, p = 1.36E-06) (Fig. 5 C).

Figure 5. Effect of INPP5B CAAX mutant on cilia localization.

(A) Domain structure of human INPP5B protein. (B) hTERT-RPE1 cells were transduced by GFP-Inpp5b or GFP-Inpp5bΔCAAX lentivirus, starved for 48 hr, and then analyzed by immunostaining with anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin antibody. Scale bar 10 micron. (C) Lengths of primary cilia in Inpp5b and Inpp5b-delta-CAAX cells. hTERT-RPE1 cells were transduced with either GFP-Inpp5b or GFP-Inpp5b-delta-CAAX lentivirus, serum starved for 48 hr, and stained with anti-acetylated alpha-tubulin antibody. Scatter plot showing distribution pattern of ciliary length (3.4±0.4 micron in INPP5B and 2.8±0.3 micron in Inpp5bΔCAAX cells, unpaired t-test, p = 1.36E-06, n >160 cilia, three independent experiments). (D) INPP5BΔCAAX mRNA failed to rescue the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with INPP5B ΔCAAX mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated α-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (E–F) Quantification of length (E) and number (F) of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with INPP5B WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with INPP5B ΔCAAX mRNA (500 ng). (N >20 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 3.9E-26 in E and * p = 9E-06 in F).

The ability of Inpp5b-delta-CAAX and INPP5B-delta-CAAX mutant to rescue the loss of INPP5B was investigated. Since those cilia-associated phenotypes in Inpp5b morphants can be partly rescued by co-injection Inpp5b WT mRNA with inpp5b MO, an Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mutant of mRNA was co-injected with 4 ng inpp5b MO (Fig. S3F-G in File S1). In Inpp5b morphants co-injected with Inpp5b WT mRNA, the KV cilia length was 6.5±0.5 micron; however, the KV cilia in morphants co-injected with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA showed shortened cilia (4.7±0.4 micron, p = 4.90E-07) (Fig. S3G in File S1). Compared with morphants co-injected with INPP5B WT mRNA, the KV cilia in embryos co-injected with INPP5B-delta-CAAX mRNA was 44±5 (p = 3.90E-26, Fig. 5E) and 4.4±0.5 micron in length (p = 9E-06, Fig. 5F). Therefore, the CAAX domain is important for INPP5B in the formation of primary cilia.

Compensatory Role of OCRL and INPP5B in Ciliogenesis in Zebrafish

The similar function and structures OCRL and INPP5B suggests that the knockdown of both 5-phosphatases may result in greater ciliary defects than the loss of either enzyme alone. To make such comparisons, a scale of phenotypes observed in zebrafish morphants, which include anophthalmia, microphthalmia, hydrocephalus, left-right axis asymmetry, generalized edema, and pigmentation defects, was established. By this scale, the normal fish was indistinguishable from the wild type fish. This scale consists of mild, with one or two of the phenotypes; moderate, with greater than two of the cilia-related phenotypes; or severe, if four or more abnormalities were present (Fig. 6A). In zebrafish treated with either 4 ng of ocrl or inpp5b MO, approximately 20% of zebrafish developed severe disease whereas when both MO are given at 4 ng, nearly 90% of zebrafish were dead within 54 hours (Fig. 6B). The combination of 2 ng ocrl and inpp5b MO resulted in equivalent number of severe phenotype as the 4 ng groups; whereas 0.5 ng of ocrl and inpp5b MO also resulted in equal numbers of mild phenotypes in morphants (Fig. 6B). Therefore, we conclude Ocrl and Inpp5b play synergistic roles in zebrafish; the loss of both genes results in a greater degree of phenotype than either gene alone.

Figure 6. INPP5B and OCRL act synergistically in eye development.

(A) Representative phenotypes of morphants co-injected with ocrl and inpp5b MO. Scale bar 250 micron. (B) Dose-dependent effect of two morpholinos in zebrafish. Control ocrl and inpp5b MO at indicated doses were injected into zebrafish embryos, and different grades of phenotypes were quantified at 48 hpf (N >250 embryos per group). (C) Transgenic mOcrl−/−:mInpp5b−/−:hINPP5B +/+ mouse eyes were sectioned and stained by H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Staining of trabecular meshwork cells in vesicular pattern (arrow), dash line indicates border of cornea and iris. Scale bar 10 micron. (D) Photoreceptor cells (arrow) from the transgenic mouse eye section stained with H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. (E) Lens epithelial cells (arrow) stained with H&E, anti-OCRL antibody (green) or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron.

The transgenic murine model of Lowe syndrome was also examined. Mice with Ocrl −/−:Inpp5b −/−:INPP5B +/+ genotype are previously characterized to show renal phenotypes resembling human disease and that introduction of INPP5B rescues the lethality of the double Ocrl/Inpp5b knockout. In these mice, the loss of Ocrl was compensated by Inpp5b expression as determined by immunohistochemistry showing normal structures of the trabecular meshwork, lens epithelial cells, and retinal outer segment (Fig. 6C–E). Expression of Inpp5b was detected in these tissues while Ocrl was not observed. Thus, human INPP5B likely compensates for the loss of OCRL in ocular tissue in this murine model.

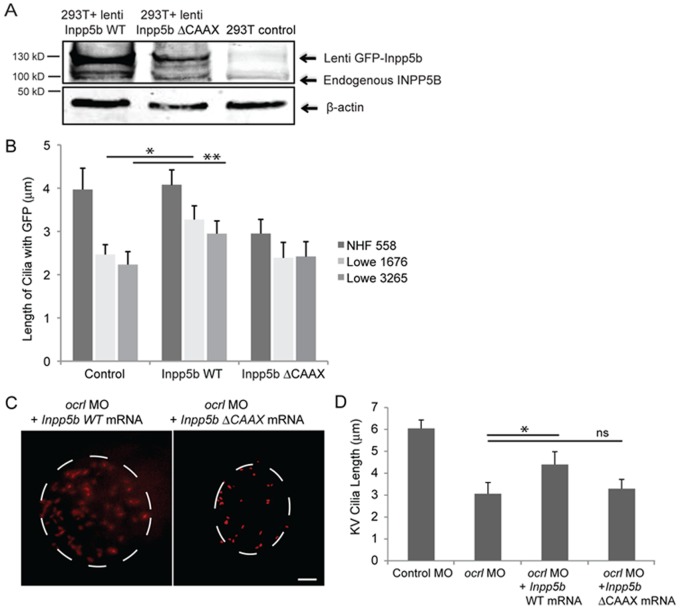

To confirm compensatory roles between OCRL and INPP5B, we examined whether INPP5B could restore ciliary length in Lowe patients fibroblasts previously characterized [35], [36], [37]. Normal human fibroblasts, Lowe 1676 and Lowe 3265 fibroblasts were transduced with GFP-Inpp5b or GFP-Inpp5b-delta-CAAX lentivirus, and cilia formation was induced by serum starvation for 48 hr. Acetylated alpha-tubulin immunostaining was performed to determine ciliary length (Fig. 7A). In Lowe 1676 patient fibroblasts, cilia lengths were noted to be longer in Inpp5b transduced cells than those treated with control lentivirus (3.3±0.3 micron vs 2.4±0.2 micron, p = 0.004). Similarly, in Lowe 3265 patient fibroblasts, cilia lengths were also noted to be longer in Inpp5b transduced cells than the control cells (2.2±0.2 micron vs 3±0.3 micron, p = 0.006) (Fig. 7B). However, Inpp5b-delta-CAAX domain did not restore the ciliary length (2.4±0.4 micron in Lowe 1676 and 2.5±0.4 micron in Lowe 3265) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. INPP5B can partly rescue the defect of OCRL in primary cilia development.

(A) INPP5B protein levels in HEK293T cells. GFP-Inpp5b lentivirus was generated in HEK293T cells; both GFP-Inpp5b and endogenous INPP5B were immunoblotted in 40 microgram lysates; beta-actin levels are shown. (B) NHF 558, Lowe 1676, and Lowe 3265 fibroblasts were transduced with control, Inpp5b or Inpp5b ΔCAAX lentivirus, serum-starved for 48-hours, and immunostained with acetylated alpha -tubulin. Quantification of cilia length is shown (n >100 cilia, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 0.004, ** p = 0.006). (C) Inpp5b mRNA partly rescued the loss of Ocrl. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with ocrl MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and ocrl MO (4 ng) with Inpp5bΔCAAX mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated α-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (D) Quantification of length of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with ocrl MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and ocrl MO (4 ng) with Inpp5bΔCAAX mRNA (500 ng). (N >20 embryos, three independent experiments, unpaired t-test, * p = 2.2E-04).

Additionally, zebrafish inpp5b was assessed for its ability to restore the loss of cilia formation in ocrl morphant zebrafish. The KV cilia in morphants co-injected with ocrl MO and Inpp5b WT mRNA were noted to be longer than those injected with ocrl MO (4.3±0.4 micron vs 3.0±0.3 micron, p = 2.19E-04) (Fig. 7C). Co-injection with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA did not restore the cilia length in the ocrl morphants (3.2±0.2 micron vs 3.0±0.3 micron, p = 0.07) (Fig. 7D). Therefore, we conclude that INPP5B can rescue the role of OCRL in development and regulation of primary cilia.

Discussion

The ciliary membrane is comprised of a wide range of proteins and lipids that are highly regulated. Previously inositol phosphatases OCRL and INPP5E have been found to be implicated in Lowe syndrome and Joubert syndrome, respectively. Here, the paralog of OCRL, INPP5B is also found to be a ciliary protein with compensatory roles in ciliogenesis in RPE cells and in zebrafish. Evidence of differential expression of OCRL and INPP5B in human and mice is also presented that potentially explains the mild phenotype of Lowe syndrome murine models.

INPP5B has been previously suggested to play a role in ciliogenesis [36]. This study shows that inositol 5-phosphatase localizes within the cilia and the localization is dependent on the CAAX prenylation domain. INPP5E deletion of CAAX domain has been reported in MORM syndrome, another ciliopathy with clinical similarities to Bardet-Beidel syndromes [27]. Recently Humbert et al. has reported a ciliary targeting sequence (FDRELYL) that precedes the CAAX domain in INPP5E [34]; however, a homology search did not yield a similar sequence in INPP5B. In this study the CAAX domain of INPP5B is demonstrated to be important in its localization and its ability to regulate ciliary length in vitro and in vivo. This suggests that the enzymes controlling prenylation are key regulator for INPP5B and INPP5E ciliary function. Based on this observation, the type I 5-phosphatase, which also contains a CAAX domain, is also predicted to localize to the cilia.

In murine knockout studies, loss of Ocrl failed to show phenotypes of cataract, glaucoma, renal failure, or brain abnormalities. Mice with Inpp5b loss resulted in spermatogenesis defect but Ocrl−/−:Inpp5b−/− resulted in embryonic lethality. The ocular distribution of these two 5-phosphatases observed here may explain the lack of ocular phenotype in the mice. In murine eyes, both Ocrl and Inpp5b are expressed in relatively equal levels; however, by both immunofluorescence and immunoblot detection, Ocrl is the predominant 5-phosphatase in the trabecular meshwork and lens epithelium. In Ocrl−/− mice, Inpp5b likely compensates for the loss of Ocrl and consistently no obvious ocular phenotypes were observed. Further, in the zebrafish, Inpp5b is found to regulate ciliogenesis in both the KV and pronephros in early embryogenesis. In fact, the loss of Inpp5b results in a more severe phenotype of anophthalmia, which is not present in the ocrl-MO injected fish, and suggests inpp5b is required in cilia development in the zebrafish.

Functionally, ocrl and inpp5b act synergistically in zebrafish cilia development. The loss of both 5-phosphatases results in greater percentage of lethality and severe phenotypes of the morphant fish than the loss of either of the enzymes. Interestingly, although inpp5e is unperturbed in these morphants, it is unable to prevent the development of these phenotypes. Our studies of human retina and RPE show that INPP5B is expressed in the outer segment of the photoreceptors and the RPE. Although absent from trabecular meshwork and lens epithelium, INPP5B in the retina may explain the lack of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) phenotype in Lowe syndrome. Clinically RP is not observed in Lowe syndrome however the vision of patients is abnormally poor, even with cataract surgery and glaucoma treatment. In fact, in certain Lowe syndrome patients we observe thinning of the outer retina, suggesting mild retinal disease may not be previously reported (Luo et al. manuscript in preparation). The compensation of INPP5B for OCRL in the retina could account for the lack of pigmentary changes seen in RP. It is possible that the loss of both OCRL and INPP5B in humans may result in anophthalmia as in the zebrafish model. In addition, mutations of INPP5B may be present in patients with a subgroup of population of RP patients.

The ocular distribution of OCRL shows the expected vesicular pattern in the trabecular meshwork, which contributes significantly to the outflow of aqueous humor. When the trabecular meshwork is dysfunctional, the resistance to aqueous humor outflow increases with a concomitant increase in intraocular pressure. Increased intraocular pressure is the leading risk factor for glaucoma and a leading causative factor for the degenerative optic neuropathy of glaucoma. The glaucoma phenotype present in Lowe syndrome may be a dysregulation of the cilia in the aqueous outflow track and may also represent a forme fruste for other forms of glaucoma [4]. The lenticular changes found in Lowe syndrome–small discoid cataracts–likely representation of failure of primary ciliogenesis of the lens epithelial cells. The immunohistochemistry of the human lens epithelial cells shows vesicular pattern that is expected of endosomes. The defective cilia may result in polarity dysregulation, which leads to a discoid cataract. Based on our results, we propose that the diverse phenotype present in Lowe syndrome is due to the dysregulation of the primary cilia, leading to polarity defects in a number of cell types and thus explains the spectrum and type of organ involvement in this genetic disorder.

Important questions remain in the mechanism of inositol 5-phosphatase regulation of cilia. Although CAAX domain is important in the ciliary localization of INPP5B and INPP5E, the critical enzyme and underlying mechanism for this targeting is not known. The role of phosphoinositides within the cilia is also not clear. Although PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 are likely the critical lipids within the cilia, the differential regulation of these lipid messengers in lens development, glaucoma pathogenesis, and retinal development is not clear. Future therapeutic targets to upregulate INPP5B in the trabecular meshwork and the lens epithelium may help ameliorate or even reverse the clinical development of ocular phenotypes in Lowe syndrome.

Supporting Information

Includes Figures S1, S2 and S3. Figure S1 Distribution of INPP5B in human retina and RPE. (A) Retina pigmented epithelial cells (arrow) from human eye section stained with H&E or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. (B) Photoreceptor cells (arrow) from human eye section stained with H&E or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. Figure S2 Subcellular distribution of INPP5B in cilia. hTERT-RPE1 cells serum starved for 48 hr and immunostained for acetylated alpha-tubulin, gamma-tubulin anti-INPP5B and DAPI. Representative image is shown (Red, alpha-tubulin, gamma-tubulin; green, INPP5B; blue, DAPI). Figure S3 Restoration of cilia defects in Inpp5b zebrafish morphants by mouse Inpp5b mRNA. (A) Inpp5b WT mRNA rescued the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated alpha-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (B-C) Quantification of number (B) and length (C) of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng). (D) Inpp5b WT mRNA rescue of inpp5b pronephric cilia formation. Representative image of pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf stage, injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng), immunostaining with acetylated α-tubulin (red). Scale bar 10 micron. (E) Pronephric cilia length of control and inpp5b MO. Pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) at 24 hpf stage were analyzed by immunostaining with acetylated alpha-tubulin and cilia length was measured. (F) Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA failed to rescue the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated alpha-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (G) Quantification of length of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA (500 ng) (6.5+0.5 micron in morphants of inpp5b MO with Inpp5b mRNA compared to 4.7+0.4 micron in morphants of inpp5b MO with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA, unpaired t-test, * p = 4.9E-07, N >20 embryos, three independent experiments).

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robert Nussbaum for generous gift of OCRL/INPP5B transgenic mice eyes. We also thank Drs. Clark Wells, Jeffrey Travers, Phil Majerus, and Robert Nussbaum for careful proofreading of manuscript. We also thank Aaron Muscarella for the care of zebrafish.

Funding Statement

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NEI K08 22058-01. http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_details.cfm?aid=8223419&icde=15619386 The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Attree O, Olivos IM, Okabe I, Bailey LC, Nelson DL, et al. (1992) The Lowe's oculocerebrorenal syndrome gene encodes a protein highly homologous to inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase. Nature 358: 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang X, Jefferson AB, Auethavekiat V, Majerus PW (1995) The protein deficient in Lowe syndrome is a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 4853–4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schurman SJ, Scheinman SJ (2009) Inherited cerebrorenal syndromes. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walton DS, Katsavounidou G, Lowe CU (2005) Glaucoma with the oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe. J Glaucoma 14: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaary EA, Rawnsley E, Marin-Padilla JM, Morse CL, Crow HC (1993) In utero detection of fetal cataracts. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 12: 234–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allingham RRD, K Freedman, S Moroi, S Shafranov, G., (2005) Shields' Textbook of Glaucoma. p11–19.

- 7. Hichri H, Rendu J, Monnier N, Coutton C, Dorseuil O, et al. (2011) From Lowe syndrome to Dent disease: correlations between mutations of the OCRL1 gene and clinical and biochemical phenotypes. Hum Mutat 32: 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitchell CA, Connolly TM, Majerus PW (1989) Identification and isolation of a 75-kDa inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase from human platelets. The Journal of biological chemistry 264: 8873–8877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lowe M (2005) Structure and function of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1. Traffic 6: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jefferson AB, Majerus PW (1995) Properties of type II inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase. J Biol Chem 270: 9370–9377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matzaris M, O'Malley CJ, Badger A, Speed CJ, Bird PI, et al. (1998) Distinct membrane and cytosolic forms of inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase II. Efficient membrane localization requires two discrete domains. The Journal of biological chemistry 273: 8256–8267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmid AC, Wise HM, Mitchell CA, Nussbaum R, Woscholski R (2004) Type II phosphoinositide 5-phosphatases have unique sensitivities towards fatty acid composition and head group phosphorylation. FEBS letters 576: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hyvola N, Diao A, McKenzie E, Skippen A, Cockcroft S, et al. (2006) Membrane targeting and activation of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1 by rab GTPases. Embo J 25: 3750–3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erdmann KS, Mao Y, McCrea HJ, Zoncu R, Lee S, et al. (2007) A role of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL in early steps of the endocytic pathway. Dev Cell 13: 377–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bothwell SP, Farber LW, Hoagland A, Nussbaum RL (2010) Species-specific difference in expression and splice-site choice in Inpp5b, an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase paralogous to the enzyme deficient in Lowe Syndrome. Mamm Genome 21: 458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hou X, Hagemann N, Schoebel S, Blankenfeldt W, Goody RS, et al. (2011) A structural basis for Lowe syndrome caused by mutations in the Rab-binding domain of OCRL1. EMBO J 30: 1659–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faucherre A, Desbois P, Nagano F, Satre V, Lunardi J, et al. (2005) Lowe syndrome protein Ocrl1 is translocated to membrane ruffles upon Rac GTPase activation: a new perspective on Lowe syndrome pathophysiology. Hum Mol Genet 14: 1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ungewickell A, Ward ME, Ungewickell E, Majerus PW (2004) The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase Ocrl associates with endosomes that are partially coated with clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 13501–13506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janne PA, Suchy SF, Bernard D, MacDonald M, Crawley J, et al. (1998) Functional overlap between murine Inpp5b and Ocrl1 may explain why deficiency of the murine ortholog for OCRL1 does not cause Lowe syndrome in mice. J Clin Invest 101: 2042–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bernard DJ, Nussbaum RL (2010) X-inactivation analysis of embryonic lethality in Ocrl wt/−; Inpp5b−/− mice. Mamm Genome 21: 186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bothwell SP, Chan E, Bernardini IM, Kuo YM, Gahl WA, et al. (2011) Mouse model for Lowe syndrome/Dent Disease 2 renal tubulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hellsten E, Bernard DJ, Owens JW, Eckhaus M, Suchy SF, et al. (2002) Sertoli cell vacuolization and abnormal germ cell adhesion in mice deficient in an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase. Biol Reprod 66: 1522–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim J, Lee JE, Heynen-Genel S, Suyama E, Ono K, et al. (2010) Functional genomic screen for modulators of ciliogenesis and cilium length. Nature 464: 1048–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luo N, West CC, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Sun L, Anderson RM, et al. (2012) OCRL localizes to the primary cilium: a new role for cilia in Lowe syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 21: 3333–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Conduit SE, Dyson JM, Mitchell CA (2012) Inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases; new players in the regulation of cilia and ciliopathies. FEBS Lett 586: 2846–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bielas SL, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Kisseleva MV, Al-Gazali L, et al. (2009) Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat Genet 41: 1032–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacoby M, Cox JJ, Gayral S, Hampshire DJ, Ayub M, et al. (2009) INPP5E mutations cause primary cilium signaling defects, ciliary instability and ciliopathies in human and mouse. Nat Genet 41: 1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coon BG, Mukherjee D, Hanna CB, Riese DJ, 2nd, Lowe M, et al (2009) Lowe syndrome patient fibroblasts display Ocrl1-specific cell migration defects that cannot be rescued by the homologous Inpp5b phosphatase. Hum Mol Genet 18: 4478–4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richardson MR, Segu ZM, Price MO, Lai X, Witzmann FA, et al. (2010) Alterations in the aqueous humor proteome in patients with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Molecular vision 16: 2376–2383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ishikawa H, Marshall WF (2011) Ciliogenesis: building the cell's antenna. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Praetorius HA, Spring KR (2005) A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Novarino G, Akizu N, Gleeson JG (2011) Modeling human disease in humans: the ciliopathies. Cell 147: 70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N (2011) Ciliopathies. The New England journal of medicine 364: 1533–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Humbert MC, Weihbrecht K, Searby CC, Li Y, Pope RM, et al. (2012) ARL13B, PDE6D, and CEP164 form a functional network for INPP5E ciliary targeting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 19691–19696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo N, West CC, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Sun L, Anderson RM, et al.. (2012) OCRL localizes to the primary cilium: a new role for cilia in Lowe syndrome. Human molecular genetics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Coon BG, Hernandez V, Madhivanan K, Mukherjee D, Hanna CB, et al. (2012) The Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1 is involved in primary cilia assembly. Human molecular genetics 21: 1835–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rbaibi Y, Cui S, Mo D, Carattino M, Rohatgi R, et al.. (2012) OCRL1 modulates cilia length in renal epithelial cells. Traffic 9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Colwill K, Wells CD, Elder K, Goudreault M, Hersi K, et al. (2006) Modification of the Creator recombination system for proteomics applications–improved expression by addition of splice sites. BMC Biotechnol 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Russell-Randall KR, Dortch-Carnes J (2011) Kappa opioid receptor localization and coupling to nitric oxide production in cells of the anterior chamber. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52: 5233–5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heller B, Adu-Gyamfi E, Smith-Kinnaman W, Babbey C, Vora M, et al. (2010) Amot recognizes a juxtanuclear endocytic recycling compartment via a novel lipid binding domain. J Biol Chem 285: 12308–12320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murga-Zamalloa CA, Atkins SJ, Peranen J, Swaroop A, Khanna H (2010) Interaction of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) with RAB8A GTPase: implications for cilia dysfunction and photoreceptor degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 19: 3591–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo N, Sun Y. (2012) Evidence of an inositol phosphatase INPP5E in cilia formation in zebrafish. Vision research under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43. Ghosh AK, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Chan L, Hitchcock PF, Swaroop A, et al. (2010) Human retinopathy-associated ciliary protein retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator mediates cilia-dependent vertebrate development. Hum Mol Genet 19: 90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peranen J, et al. (2007) A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell 129: 1201–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schneider I, Houston DW, Rebagliati MR, Slusarski DC (2008) Calcium fluxes in dorsal forerunner cells antagonize beta-catenin and alter left-right patterning. Development 135: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sarmah B, Winfrey VP, Olson GE, Appel B, Wente SR (2007) A role for the inositol kinase Ipk1 in ciliary beating and length maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 19843–19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yen HJ, Tayeh MK, Mullins RF, Stone EM, Sheffield VC, et al. (2006) Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes are important in retrograde intracellular trafficking and Kupffer's vesicle cilia function. Hum Mol Genet 15: 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Includes Figures S1, S2 and S3. Figure S1 Distribution of INPP5B in human retina and RPE. (A) Retina pigmented epithelial cells (arrow) from human eye section stained with H&E or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. (B) Photoreceptor cells (arrow) from human eye section stained with H&E or anti-INPP5B antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar 10 micron. Figure S2 Subcellular distribution of INPP5B in cilia. hTERT-RPE1 cells serum starved for 48 hr and immunostained for acetylated alpha-tubulin, gamma-tubulin anti-INPP5B and DAPI. Representative image is shown (Red, alpha-tubulin, gamma-tubulin; green, INPP5B; blue, DAPI). Figure S3 Restoration of cilia defects in Inpp5b zebrafish morphants by mouse Inpp5b mRNA. (A) Inpp5b WT mRNA rescued the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated alpha-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (B-C) Quantification of number (B) and length (C) of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng). (D) Inpp5b WT mRNA rescue of inpp5b pronephric cilia formation. Representative image of pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf stage, injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng), immunostaining with acetylated α-tubulin (red). Scale bar 10 micron. (E) Pronephric cilia length of control and inpp5b MO. Pronephric cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with control MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) or inpp5b MO (4 ng) and Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) at 24 hpf stage were analyzed by immunostaining with acetylated alpha-tubulin and cilia length was measured. (F) Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA failed to rescue the loss of inpp5b. KV cilia of zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA (500 ng) at 6-somite stage were immunostained with acetylated alpha-tubulin (red), representative images are shown (dash line indicates border of KV). Scale bar 10 micron. (G) Quantification of length of KV cilia in zebrafish embryos injected with inpp5b MO (4 ng), inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b WT mRNA (500 ng) and inpp5b MO (4 ng) with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA (500 ng) (6.5+0.5 micron in morphants of inpp5b MO with Inpp5b mRNA compared to 4.7+0.4 micron in morphants of inpp5b MO with Inpp5b-delta-CAAX mRNA, unpaired t-test, * p = 4.9E-07, N >20 embryos, three independent experiments).

(DOCX)