Abstract

Background & Aims

Electroneutral NaCl absorption across small intestine contributes importantly to systemic fluid balance. Disturbances in this process occur in both obstructive and diarrheal diseases, eg, cystic fibrosis, secretory diarrhea. NaCl absorption involves coupling of Cl−/HCO3− exchanger(s) primarily with Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (Nhe3) at the apical membrane of intestinal epithelia. Identity of the coupling Cl−/HCO3− exchanger(s) was investigated using mice with gene-targeted knockout (KO) of Cl−/HCO3− exchangers: Slc26a3, down-regulated in adenoma (Dra) or Slc26a6, putative anion transporter-1 (Pat-1).

Methods

Intracellular pH (pHi) of intact jejunal villous epithelium was measured by ratiometric microfluoroscopy. Ussing chambers were used to measure transepithelial 22Na36Cl flux across murine jejunum, a site of electroneutral NaCl absorption. Expression was estimated using immunofluorescence and quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Basal pHi of DraKO epithelium, but not Pat-1KO epithelium, was alkaline, whereas pHi in the Nhe3KO was acidic relative to wild-type. Altered pHi was associated with robust Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in the DraKO and Nhe3KO villous epithelium, respectively. Contrary to genetic ablation, pharmacologic inhibition of Nhe3 in wild-type did not alter pHi but coordinately inhibited Dra. Flux studies revealed that Cl− absorption was essentially abolished (>80%) in the DraKO and little changed (<20%) in the Pat-1KO jejunum. Net Na+ absorption was unaffected. Immunofluorescence demonstrated modest Dra expression in the jejunum relative to large intestine. Functional and expression studies did not indicate compensatory changes in relevant transporters.

Conclusions

These studies provide functional evidence that Dra is the major Cl−/HCO3− exchanger coupled with Nhe3 for electroneutral NaCl absorption across mammalian small intestine.

The small intestinal process of transepithelial NaCl absorption is known to involve the coupled activity of Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− exchangers.1,2 Electroneutral NaCl absorption (so-called because absorption is not associated with transepithelial electrical currents) provides a mechanism for copious NaCl and water absorption across the intestine, especially under physiologic conditions such as the stress response. Earlier studies to identify the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) involved in coupled NaCl absorption established that SLC9A3, ie, NHE3, is the principal Na+/H+ exchanger isoform responsible for transepithelial Na+ absorption at the apical membrane of intestinal epithelia. The evidence for predominance of NHE3 in transepithelial Na+ absorption came, by necessity, from studies of native intestinal mucosa using isoform-specific pharmacologic inhibitors and measurements of transepithelial isotopic flux across Nhe2 and Nhe3 knockout (KO) mouse intestine.3–5 Other NHE isoforms, NHE2 (SLC9A2) and NHE8 (SLC9A8), have also been reported to contribute but have less dominant roles under basal conditions in the small intestine.3,6,7

Recent studies indicate that coupled Cl−/HCO3− exchanger(s) for NaCl absorption are likely members of the SLC26A family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Of the 10 family members, 2 members have been localized to the apical membrane of mammalian intestinal epithelia. SLC26A3, also known as down-regulated in adenoma (DRA), normally exhibits high rates of Cl−/HCO3− exchange, and loss-of-function mutations of SLC26A3 are responsible for the human genetic disease congenital Cl− losing diarrhea (CLD).8 –10 SLC26A6, also known as PAT-1, is a robust Cl−/HCO3− exchanger but also exchanges sulfate, oxalate, and formate at lower rates.11–13 Some, but not all,14 studies of recombinant DRA and PAT-1 provide evidence that these transporters may have stoichiometries consistent with electrogenicity (PAT-1 1Cl−:2 HCO3−; DRA 2Cl−:1HCO3−).12,15 Based on the opposing stoichiometries, it has been further proposed that electroneutrality of coupled NaCl absorption is preserved by paired cellular operation of the 2 anion exchangers.15

Although classical descriptions of coupled NaCl absorption have come from studies of the small intestine, notably rabbit ileum,16 studies of colonic epithelium have provided indirect evidence that Dra is the major Cl−/HCO3− exchange involved in coupled NaCl absorption. Investigations of CLD patients led to the elucidation of DRA as a major anion exchanger in the large intestine,8 which has been confirmed using brush-border membrane vesicles from colonic epithelium of DraKO mice.17 Evidence that Dra couples with Nhe3 for NaCl absorption was provided in studies showing that Dra expression is up-regulated in the Nhe3KO colon18 and that Nhe3 expression is up-regulated in the DraKO mouse colon (although the latter finding may be complicated by the effects of hyperaldosteronism secondary to dehydration).17 In contrast, less is known about the identity of the coupled Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in small intestine. The available findings indicate several differences from colonic NaCl absorption. Up-regulation of Dra expression was not detected in the Nhe3KO small intestine, and overt changes in crypt morphology found in the DraKO colon were not evident in the small bowel.17,18 In addition, the expression of Dra and Nhe3 is less in the small intestine as compared with the colon, and Pat-1, which is weakly expressed in the large intestine, presents an additional possibility for coupling with Nhe3.18,19

Murine jejunum provides a useful model of coupled NaCl absorption in the small intestine by showing high rates of electroneutral NaCl absorption similar to that described in studies of human ileum, rat jejunum, and rabbit ileum.1,16,20 –22 Identification of the apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchanger(s) involved in coupled NaCl absorption across the small intestine requires that studies be performed using native intestine. Murine jejunum has the advantages of providing sufficient intestinal preparations for bidirectional isotopic NaCl flux measurements and the opportunity to perform studies on mice with gene-targeted KO of the anion exchangers, which is important in that specific inhibitors or stimulants that discriminate between Slc26a isoforms are not available. Therefore, in the present study, ex vivo intestinal studies were performed using mice with gene-targeted deletions of Pat-1 and Dra to assess their relative contribution to coupled NaCl absorption across the small intestine.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The experiments in this study were performed using mice with gene-targeted disruptions of the murine homologs of Slc26a3 (Dra),17 Slc26a6 (Pat-1),23 or Slc9a3(Nhe3)5 on a mixed genetic background. All comparisons of homozygous KO (−/−) mice were made with sex- and age-matched (+/+) siblings (wild-type; WT). The mutant mice were identified by using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based analysis of tail snip DNA, as previously described.20 All mice were maintained ad libitum on standard laboratory chow (Formulab 5008 Rodent Chow; Purina Mills, St Louis, MO) and tap water. The drinking water of the DraKO, Nhe3KO and WT littermate mice routinely contained 50% strength Pedialyte (Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH) to prevent dehydration in the KO mice secondary to diarrhea.17 Analysis of blood from Pedialyte-treated DraKO mice did not reveal a difference in hematocrit from WT mice. There was a small, but nonsignificant, increase in blood pH (WT, 7.17 vs DraKO, 7.26) coincident with moderately increased HCO3− concentration and pCO2, indicating a degree of metabolic alkalosis with respiratory compensation (Supplementary Table 1; see Supplementary material online at www.gastrojournal.org). Mice (age, 2– 4 months) were fasted overnight prior to experimentation but were provided with drinking water ad libitum. The mice were housed in the AAALAC-accredited Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center animal facility. All experiments involving animals were approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee.

Transepithelial 22Na36Cl Flux Analysis

The method for transepithelial 22Na36Cl flux across murine jejunum has been previously described.24 Briefly, midjejunal sections were stripped of external muscle layers before mounting on Ussing chambers (0.25-cm2 surface area). Transepithelial short-circuit current (Isc; μEq/cm2 · h) and transepithelial conductance (Gt; mS/cm2) were measured using an automatic voltage clamp (VCC-600; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). Mucosal and serosal sides of each section were independently bathed with Krebs bicarbonate Ringers solution (KBR) gassed with 95% O2:5% CO2 (pH 7.4; 37°C). In some experiments to evaluate the effect of low luminal HCO3− concentration on Cl− absorption, HCO3− in the luminal bath was substituted with the buffer TES (25 mmol/L) and gassed with 100% O2 (pH 7.4). All ex vivo preparations were treated with indometh-acin (1 μmol/L, bilateral) and tetrodotoxin (0.1 μmol/L, serosal) to minimize the effects of endogenous prosta-glandins and neural tone, respectively.25,26 Approximately 5 μCi of 22Na and 36C1 were added to the “source” bathing medium, and, following a 30-minute equilibration period, triplicate aliquots (200 μL) were taken from the “sink” side at the beginning and end of the 30-minute flux period. To determine the effect of cAMP on NaCl absorption, intracellular cAMP was stimulated by the bilateral addition of 10 μmol/L forskolin and 100 μmol/L isobutylmethyl xanthine for 30 minutes prior to a second flux period. Samples were analyzed for 22Na and 36C1 by sequential counting in gamma radiation and liquid scintillation systems (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT). The rate of radioisotope transfer was used to calculate unidirectional mucosal-to-serosal (JM-S), serosal-to-mucosal (JS-M), and net fluxes (JNET = JM-S − JS-M) of 22Na and 36Cl. Flux values for each mouse were averaged from 1 to 3 pairs of jejunal preparations matched within 15% difference of the Gt. For net fluxes, a positive value indicates net absorption (mucosal-to-serosal), and a negative value indicates net secretion (serosal-to-mucosal).

Intracellular pH Measurement

The method used for imaging villous epithelial cells in intact murine intestinal mucosa has been previously described.27,28 Briefly, small intestine stripped of the external muscle layers was mounted luminal side up in a horizontal Ussing-type perfusion chamber where luminal and serosal surfaces were independently bathed. The mucosa was incubated on the luminal side with 16 μmol/L of 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxy-fluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) for 10 minutes before superfusion of the luminal surface. The luminal superfusate contained (in mmol/L): 55.0 NaCl, 55.0 Na isethionate, 25.0 NaHCO3, 5.0 Na TES, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 1.2 Ca gluconate, 1.2 Mg gluconate, 10.0 glucose, and 6.8 mannitol (pH 7.4; 37°C; gassed with 95% O2:5% CO2). The serosal superfusate was identical except that Cl− was replaced with isethionate− and contained 1 μmol/L of 5-(N-ethyl-n-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA) to block the basolateral membrane Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. Intracellular pH (pHi) from 10 villous epithelial cells of an immobilized villus was measured by dual excitation at 440- and 495-nm wavelengths and imaged at 535-nm emission. The 440/495-nm ratio was converted to pHi using a standard curve. Intrinsic buffering capacity (βi) was estimated by the ammonium prepulse technique, and the total buffering capacity (βtotal) was calculated from the equation βtotal = βi + βHCO3− = βi + 2.3 × [HCO3−i], where βHCO3− is the buffering capacity of the HCO3−/CO2 system. Rates of apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange (in mmol/L HCO3−/min) were calculated by βtotal × ΔpHi/Δt during the first 90-second period during removal and readdition of Cl− in the luminal superfusate. For Na+/H+ exchange, HCO3− was replaced with TES (gassed with 100% O2), and Na+ was replaced by N-methyl-D-gluconate in the serosal superfusate. Rates of apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange were estimated from βi × ΔpHi/Δt during the first 90-second period during removal and replacement of luminal Na+.

Immunofluorescence

Dra protein expression in frozen sections (4 μm thick) of jejunum and cecum was estimated by immunofluorescence using rabbit anti-human DRA antibody, as previously described.29

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Dra, Pat-1, Nhe3, and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (Cftr) in whole jejunal samples was measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using specific primers in a LightCycler system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). mRNA expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene L32 ribosomal protein. See Supplementary Figure 1 for details (see Supplementary material online at www.gastrojournal.org).

Materials

BCECF-AM was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tetrodotoxin and forskolin were obtained from Biomol International L.P. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Radioisotopes were obtained from GE Healthcare (22Na; Piscataway, NJ) and Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (36Cl; Waltham, MA). All other materials were obtained from either Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Springfield, NJ).

Statistical Analysis

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Data between 2 treatment groups were compared using a 2-tailed unpaired Student t test assuming equal variances between groups. Data from multiple treatment groups were compared using a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Tukey t test. A probability value of P <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

KO of Dra and Nhe3 Has Reciprocal Effects on Steady-State pHi in Villous Epithelium

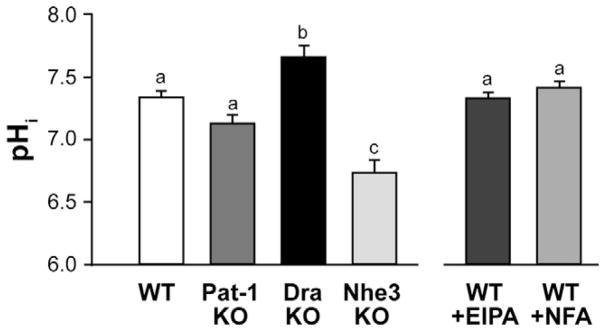

Apical membrane acid-base transporters primarily determine epithelial cell pHi under experimental conditions that eliminate basolateral membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange and Nhe1 activities. Figure 1 shows the steady-state pHi of the midvillous epithelium for WT, Pat-1KO, DraKO, and Nhe3KO intestine under these conditions. As compared with WT, the pHi of Pat-1KO villous epithelium was unchanged, whereas pHi in the DraKO epithelium was significantly alkaline. An opposite effect, acidic pHi, was present in the Nhe3KO villous epithelium. Pharmacologic inhibition of either Dra or Nhe3,10 in contrast to genetic ablation, did not affect pHi in WT villous epithelium, suggesting coordinate inhibition of the two exchangers.

Figure 1.

Intracellular pH (pHi) in intact villous epithelium. Left panel: basal pHi in WT, Pat-1 KO, Dra KO, and Nhe3 KO intestine. Right panel: effect of inhibiting apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange with 100 μmol/L EIPA or Cl−/HCO3− exchange with 100 μmol/L niflumic acid (NFA) in WT epithelium. *Experimental conditions accentuate the effect of apical membrane acid-base transporters (see Results section). a,b,cMeans without the same letters are significantly different (n = 4–8 mice).

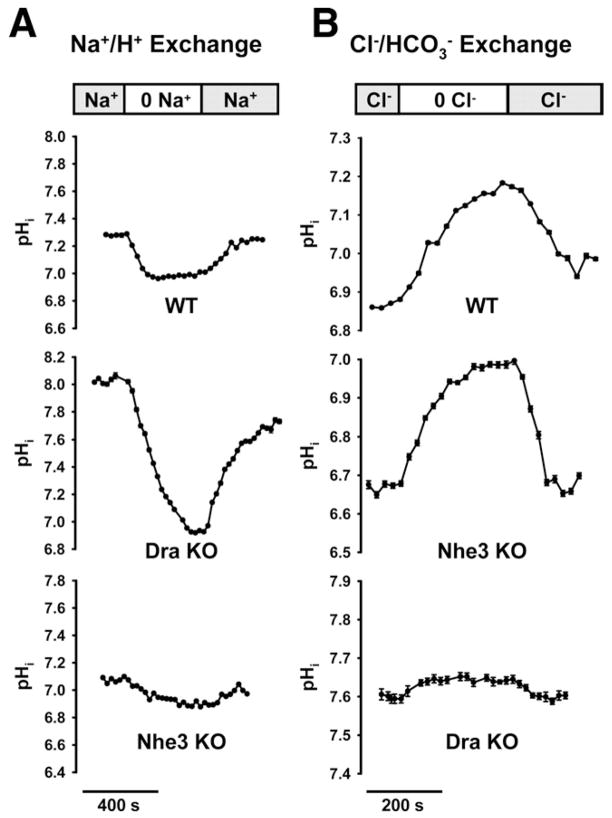

Uncoupled Activity of Dra and Nhe3 in the Villous Epithelium

To investigate whether genetic ablation of either Dra or Nhe3 yielded “uncoupled” activities of the opposing exchanger, exchange rates were measured in the midvillous epithelium of the jejunum. As estimated from pHi changes induced by luminal Na+ substitution (Figure 2A), the DraKO epithelium exhibited robust Na+/H+ exchange activity as compared with WT (WT, 17.5 ± 2.1; DraKO, 37.8 ± 6.1 mmol/L/min, P <.05, n = 3). Verification that most Na+/H+ exchange in the jejunal villi represented Nhe3 activity was shown by a diminutive response to Na+ substitution in the Nhe3KO (Nhe3KO, 5.9 ± 1.7 mmol/L/min; n = 3). Based on measurements of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by luminal Cl− replacement (Figure 2B), vigorous apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange was also present in the Nhe3KO as compared with WT villous epithelium (WT, 15.5 ± 1.3; Nhe3KO, 22.8 ± 4.7 mmol/L/min; n = 3). Verification that most Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the jejunal villous epithelium represents Dra activity was shown by the modest pHi response to Cl− substitution in the DraKO intestine (DraKO, 1.5 ± 0.5 mmol/L/min; n = 5). This residual Cl−/HCO3− exchange, ostensibly attributable to Pat-1 activity, approximates the magnitude of decreased Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the Pat-1KO jejunum as compared with WT (2.9 mmol/L/min, ie, the difference between WT, 16.6 ± 2.7 and Pat-1KO, 13.7 ± 2.2 mmol/L/min; n = 4 – 6). Thus, any suppression of Pat-1 activity appears to be a relatively minor component of the decreased Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in the DraKO.

Figure 2.

Functional activities of apical membrane Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− in intact villous epithelium. (A) Na+/H+ exchange activity in WT, Dra KO, and Nhe3 KO jejunum as measured by removal and replacement of luminal Na+ (representative of 3 mice). (B) Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in WT, Nhe3 KO, and Dra KO measured by removal and replacement of luminal Cl− (representative of 3 mice).

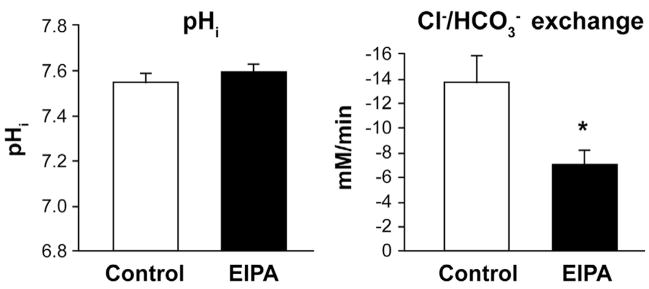

Coordinate Inhibition of Dra Activity During EIPA Inhibition of Nhe3

The lack of pHi changes in the WT villous epithelium during EIPA treatment (Figure 1) suggested simultaneous inhibition of Dra. To examine this hypothesis, Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity was measured in the jejunal villous epithelium treated with luminal EIPA (100 μmol/L) to inhibit Nhe3 activity. Pat-1KO jejunum was used to eliminate the contribution of Pat-1 and thereby isolate Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity. As shown in Figure 3, EIPA did not affect pHi but reduced Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity by ~48% as compared with control. The residual or unaffected Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity (~52%) suggests that a complement of Dra activity is independent of Nhe3, eg, involved in net HCO3− secretion.

Figure 3.

Basal pHi and isolated Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange rates during inhibition of apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange in Pat-1 KO jejunal villous epithelium. Apical membrane Na+/H+ (Nhe3) exchange was inhibited with 100 μmol/L EIPA. Control was treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). *Significantly different from control (n = 6–9).

Dra Provides Transepithelial Cl− Absorption During Electroneutral NaCl Transport Across Murine Jejunum

Previous isotopic flux studies have shown electroneutral NaCl absorption to be a major transport characteristic of the murine jejunum.3,20 Therefore, to investigate the identity of the Cl−/HCO3− exchanger coupled with Nhe3, we performed 22Na36Cl transepithelial flux studies on jejunum from Pat-1KO, DraKO, and WT littermate mice. As shown in WT jejunum (Table 1), the absorptive flux of both Na+ (JM-SNa) and Cl− (JM-SCl) exceeds the secretory flux (JS-MNa and JS-MCl, respectively), indicating net absorption of Na+ and Cl− under basal conditions. The Isc is near zero, consistent with classical “electroneutral” NaCl absorption. In the DraKO intestine, net Na+ absorption was slightly reduced (−3.7 μEq/cm2 · h) compared with WT, but the change was not statistically different. The difference appeared to be due to decreased JM-SNa (−2.7 μEq/cm2 · h), but this change also was not statistically significant. In contrast to unimpaired Na+ flux, net Cl− absorption was essentially abolished in the DraKO as compared with WT. This change was due entirely to a reduction in the absorptive JM-SCl, indicating that Dra is the major pathway for Cl− absorption. A small increase in the basal Isc of the DraKO jejunum was also noted. In additional studies, increased cAMP abolished net Na+ absorption and reversed net Cl− absorption to net Cl− secretion with increased Isc in both the DraKO and WT intestine (Supplementary Table 2; see Supplementary material online at www.gastrojournal.org). Interestingly, the JM-SCl in the DraKO remained significantly reduced relative to WT, indicating that Dra provides a finite amount of Cl− absorption during cAMP stimulation.

Table 1.

Basal Unidirectional and Net Flux of Na+ and Cl−, Isc, and Gt of Jejunal Preparations From WT and Dra KO Mice

|

JNa+ |

JCl− |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-S | S-M | Net | M-S | S-M | Net | Isc | Gt | No. | |

| WT | 36.8 ± 2.3 | 23.1 ± 1.6 | 13.7 ± 2.1 | 35.6 ± 2.0 | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 12.5 ± 1.8 | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 53.6 ± 1.7 | 9 |

| Dra KO | 34.1 ± 1.5 | 24.1 ± 0.8 | 10.0 ± 1.2 | 21.7 ± 1.9a | 22.1 ± 1.4 | −0.4 ± 1.5a | −1.3 ± 0.2a | 51.5 ± 1.8 | 8 |

NOTE. J and Isc in μEq/cm2 · h; Gt in mS/cm2.

J, ion flux; Isc, short-circuit current; Gt, transepithelial conductance; S-M, serosal-to-mucosal; M-S, mucosal-to-serosal.

Significantly different from WT, P <.05.

Unidirectional and net fluxes of 22Na36Cl across the jejunum of Pat-1 mice are shown in Table 2. Net Na+ absorption across the Pat-1KO jejunum was modestly, although not significantly, reduced compared with WT (P = .064). It is difficult to draw conclusions from this observation because the reduced Na+ absorption was due to both increased JS-MNa (+2.3 μEq/cm2 · h) and decreased JM-SNa (−2.1 μEq/cm2 · h). In contrast to the DraKO intestine, net Cl− absorption was not significantly reduced in the Pat-1KO relative to WT jejunum. A small decrease in JM-SCl flux was noted, but this change did not attain statistical significance. Because the small intestine may exhibit low luminal HCO3− concentrations during periods of a prandial cycle,21 we asked whether nominal removal of luminal HCO3− with unchanged pH (7.4) might reveal a larger contribution of PAT-1 to basal Cl− absorption. However, the magnitude of the Pat-1-dependent flux was not greater than that measured in the presence of 25 mmol/L luminal HCO3− (Part-1 ΔJM-SCl = 2.1 vs 2.9 μEq/cm2 · h, respectively; n = 7–9) (Supplementary Table 3; see Supplementary material online at www.gastrojournal.org). In studies of cAMP stimulation, the Pat-1KO and WT intestine also responded with complete inhibition of net NaCl absorption and the induction of net Cl− secretion (Supplementary Table 4; see Supplementary material online at www.gastrojournal.org). Interestingly, there was a tendency for a reduction in net Cl− secretion, which resulted from decreased JS-MCl flux in the Pat-1KO intestine.

Table 2.

Basal Unidirectional and Net Flux of Na+ and Cl−, Isc, and Gt of Jejunal Preparations From WT and Pat-1 KO Mice

|

JNa+ |

JCl− |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-S | S-M | Net | M-S | S-M | Net | Isc | Gt | No. | |

| WT | 37.7 ± 2.2 | 21.7 ± 1.7 | 16.0 ± 1.7 | 29.1 ± 1.9 | 16.3 ± 0.8 | 12.8 ± 2.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 52.2 ± 2.6 | 8 |

| Pat-1 KO | 35.6 ± 2.0 | 24.0 ± 1.9 | 11.6 ± 1.4 | 26.2 ± 1.7 | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 49.7 ± 1.2 | 10 |

NOTE. J and Isc in μEq/cm2 · h; Gt in mS/cm2.

J, ion flux; Isc, short-circuit current; Gt, transepithelial conductance; S-M, serosal-to-mucosal; M-S, mucosal-to-serosal.

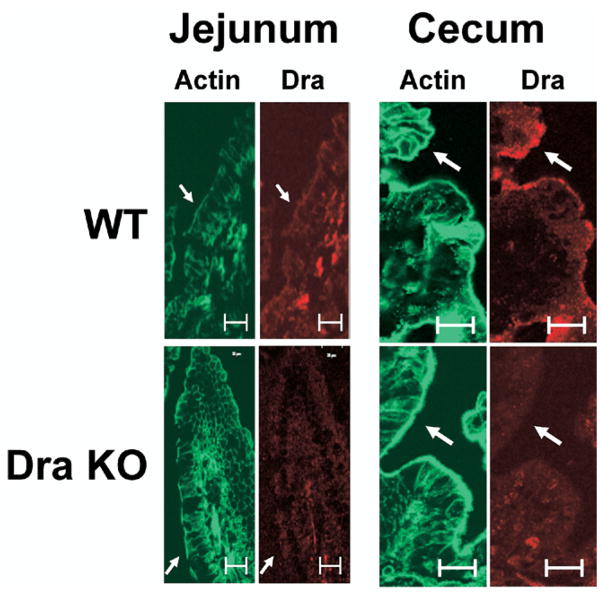

Dra Protein Expression in Murine Jejunum and the Absence of Compensatory Changes in the Expression of Pat-1 or Nhe3 in the DraKO

Previous studies have demonstrated that Dra expression in the small intestine is significantly less relative to large intestine,30 but this expression level is physiologically relevant given the expansive surface area of the small intestine (~20-fold greater than the large intestine based on organ length and the presence of villi). In support of studies demonstrating a major role for Dra in small intestinal Cl− absorption, the expression of Dra protein was evaluated by immunofluorescence of the jejunum using rabbit anti-human DRA antibody.29 As shown in Figure 4, specific Dra staining along the midvillus in the murine jejunum was present but modest when compared with the surface epithelium of the cecum where Dra expression is greatest.30 Because compensatory changes in the expression of apical membrane transporters may occur in the DraKO intestine, quantitative RT-PCR was used to evaluate alterations in the expression of Pat-1, Nhe3, or Cftr. However, no significant differences were detected in the mRNA expression of the transporters in the DraKO as compared with Dra WT (Supplementary Figure 1). Similarly, compensation by up-regulation of Dra mRNA expression in the Pat-1KO also was not apparent.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescent localization of Dra (red) and phalloidin (actin, green) in the jejunal and cecal epithelium of WT and Dra KO mice. WT shows immunolocalization of Dra to apical and subapical compartments at the apical membrane that is not present in the Dra KO mice. Expression of immunoreactive Dra is modest in the jejunum villous epithelium relative to the surface epithelium of the cecum (representative of 4 experiments). Bars = 25 μm; arrows indicate apical membrane.

Discussion

Intestinal studies of mice with gene-targeted deletions of the apical membrane anion exchangers Dra and Pat-1 provide functional evidence that Dra couples with Nhe3 for electroneutral NaCl absorption across murine jejunum. When experimental conditions accentuated the effects of apical membrane acid-base transport on pHi, it was found that genetic ablation of either Dra or Nhe3 had opposite effects on pHi of the villous epithelium. In the DraKO epithelium, pHi was alkaline relative to WT. Although reasonable for loss of a HCO3− exporter, alkalinization of pHi was not detected in the Pat-1KO jejunum (or duodenum28). This led to the hypothesis that alkaline pHi in the DraKO villous epithelium results from continued activity of “uncoupled” Nhe3. Three lines of evidence support this hypothesis: (1) vigorous Na+/H+ exchange activity was present at the apical membrane of the DraKO epithelium; (2) isotopic flux studies showed that Na+ absorption, a function of Nhe3,3 was unaffected in the DraKO intestine; and (3) luminal pH has previously been shown to be acidic in the DraKO colon, suggesting ongoing proton secretion.17 Evidence of coupling was also provided by the Nhe3KO villous epithelium where pHi was found to be acidic relative to WT. This may reflect loss of proton export, but similar reasoning supports the hypothesis that the acidic pHi is secondary to continued activity of “uncoupled” Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange: (1) robust Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity was present at the apical membrane of Nhe3 villous epithelium; (2) isotopic flux studies have shown that net Cl− absorption is unchanged in the Nhe3KO jejunum3; and (3) measurements of luminal pH find intestinal alkalinity in the Nhe3KO mice.5

Unlike genetic ablation, pharmacologic inhibition of Nhe3 with EIPA or Dra with niflumic acid in WT epithelium did not alter pHi, suggesting coincident inhibition of both exchangers. Coincident inhibition was confirmed by showing that EIPA inhibition of Na+/H+ exchange reduced ~50% of “isolated” Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Previous studies have proposed that the mechanism of coupling between Cl−/HCO3− and Na+/H+ exchangers involves local pHi changes,1,2,31 and recent studies using recombinant hDRA show inhibition by cellular acidification with butyrate.10 However, it is noteworthy that Dra activity in intestinal mucosa was not inhibited by low pHi in the Nhe3KO villous cells, which may indicate that inhibition requires the presence of both exchangers in the apical membrane. Incomplete EIPA inhibition of Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange (Figure 3) also revealed that a finite fraction of Dra activity is independent of Nhe3, which is consistent with finding Dra-dependent Cl− absorption after cAMP inhibition of NaCl absorption (Supplementary Table 2). This component of Dra activity is likely involved in net HCO3− secretion in the small intestine and may require CFTR-mediated recycling of Cl−.27

Isotopic flux studies provided strong evidence of Dra’s involvement in intestinal NaCl absorption by showing that net Cl− absorption is essentially eliminated in the DraKO jejunum and little changed in the Pat-1KO jejunum. There was a tendency for small decreases of net Na+ absorption in both mouse models, but this change did not attain statistical significance. Although net Cl− absorption was not significantly decreased in the Pat-1KO jejunum, the unidirectional JClm-s did attain statistical significance when measured in the absence of luminal HCO3− to accentuate the driving force for Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity. The small reduction of net NaCl absorption measured in the Pat-1KO jejunum matches well with another report of bidirectional isotopic flux studies in the Pat-1KO jejunum.32 Although the decreases in net NaCl absorption were found to be significant in that study, the overall magnitude of the net NaCl absorption was ~50% less than reported in the present investigation. This difference is possibly methodologic because the earlier study included 10 μmol/L amiloride in the luminal bath, which may have untoward effects on Na+/H+ exchange during sustained exposure in a transepithelial flux experiment.

Murine jejunum is a model of coupled NaCl transport in native mammalian small intestine. The present data are applicable to human ileal transport where coupled NaCl has been widely documented, but segmental and species differences exist with regard to the NaCl absorptive process in other segments of the small intestine.21 Human jejunum is typically considered to exhibit only Na+/H+ exchange, which is necessary for HCO3− absorption from duodenal effluent.33 A similar transport function has been documented in other species, but most investigations, including those on human, focused on proximal rather than middle to distal regions of the jejunum.34,35 Consequently, rat jejunum has been shown to exhibit only Na+/H+ exchange,34 whereas later studies documented the presence of Cl−/OH− exchange.22 Relevant to this discussion, the small intestine has also been shown to have low levels of Dra and Nhe3 expression when compared with large intestine,18,36 which has led to conflicting reports about jejunal Dra expression in the rat.37,38 The present study found that murine jejunum is consistent with this expression pattern, ie, low levels of immunoreactive Dra protein were found in jejunum relative to murine cecum. However, as demonstrated by the flux studies, the low level of expression is more than compensated by the expansive epithelial surface area of the small intestine where rates of Cl− absorption typically exceed (~2-fold) that measured across the large intestine.39 Another concern raised was that DraKO or Pat-1KO jejunum may have compensatory changes in the contribution of other transporters to the process of NaCl absorption. However, mRNA expression studies did not reveal increased Dra expression in the Pat-1KO or increased Pat-1 expression in the DraKO intestine. Microfluorimetry studies also did not reveal significant changes in Pat-1 activity in the DraKO villous epithelium. Lack of compensation between the two anion exchanger is consistent with evidence from murine duodenum using these mouse models.28 Isotopic flux studies found no significant change in net Na+ absorption nor was Nhe3 mRNA expression altered in the DraKO jejunum. Thus, reciprocal changes in expression between Dra and Nhe3, as has been previously reported for the DraKO colon,17 are not a feature of the small intestine.

The present findings do not support a recent proposal from studies of recombinant DRA and PAT-1 that parallel activities of the two proteins are responsible for electroneutral Cl− absorption.15,40 Cellular measurements of apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the mouse models show dominant activity of Dra with little contribution by Pat-1 in the jejunal villous epithelium. Similarly, a previous study has shown dominance of Pat-1 over Dra activity in the duodenal upper villous epithelium.28 Thus, significant parallel cellular activities are unlikely. Measurements of Isc in the flux studies also provide compelling evidence that Dra activity is electroneutral. The rates of net Cl− absorption across the WT jejunum ranged from 12.5 to 13.2 μEq/cm2 · h. If Dra exhibits 2Cl−:1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry, then loss of an outward current from Dra activity in the DraKO jejunum would result in 6.3– 6.6 μEq/cm2 · h increase in the Isc, yet the Isc was only increased by 1.1 μEq/cm2 · h. Given the 1Na+:1H+ exchange stoichiometry for NHE3,41 the electroneutrality of coupled NaCl absorption suggests that Dra exhibits 1Cl−:1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that DraKO jejunum demonstrated a small increase in the basal Isc. Although the ionic basis of the current has not been investigated, it is possible that the inward current results from Pat-1 1Cl−in/2HCO3−out activity revealed in the absence of Dra and thus may indicate a minor component of parallel Pat-1-Dra activity. An alternative explanation for increased basal Isc in the DraKO intestine may be epithelial cell alkalinity (Figure 1), which can induce hyperpolarization of the membrane potential through the activation of basolateral membrane K+ channels.42

Identification of the apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchangers involved in the process of coupled NaCl absorption is fundamental to creating an accurate model of electrolyte transport across the mammalian small intestine. Previous evidence that Dra couples with Nhe3 has come from investigations of colonic expression patterns, recombinant protein studies, and clinical data. The present study supports this conclusion by providing functional evidence that Dra is the major Cl−/HCO3− exchanger coupled with Nhe3 for electroneutral NaCl absorption across native small intestine. Isotopic flux studies of KO mice show that Dra provides >80% of basal Cl− absorption in a section of small intestine where Nhe3 Na+/H+ exchange dominates net Na+ absorption.10 Dra also provides a component of Cl− absorption during cAMP stimulation that may be related to a role in transepithelial HCO3− secretion. Pat-1, on the other hand, provided <20% of basal Cl− absorption. Coupling of Dra and Nhe3 was evident from studies of villous epithelium where it was shown that genetic ablation of each exchanger has opposing effects on pHi and that pharmacologic inhibition of Nhe3 suppressed Dra activity. The findings of the present study on the DraKO intestine may be relevant to CLD patients. A propensity toward alkaline epithelial pHi would negatively impact nutrient absorption and cellular processes of proliferation/apoptosis, thus contributing to disease morbidity. Furthermore, given the central role of Dra in intestinal NaCl absorption, a more general consideration is whether manipulation of DRA activity would be useful as a therapeutic strategy for relevant human diseases such as secretory diarrhea or the obstructive intestinal manifestations of cystic fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK48816, to L.L.C.; T32-RR-07004, to J.E.S.; CA-95172, to C.W.S.; DK074459, to R.K.G.; DK54016, to P.K.D.) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CLARKE05G0, CLARKE06P0, to L.L.C.).

The authors thank Kathy Curtis and Dr. F. Anthony Mann at the University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine for their assistance in the blood gas analyses.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Cftr

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CLD

congenital chloride-losing diarrhea

- Dra

down-regulated in adenoma

- EIPA

5-(N-ethyl-n-isopropyl)-amiloride

- Gt

transepithelial conductance

- Isc

short-circuit current

- J

ion flux

- KO

knockout

- M-S

mucosal-to-serosal

- NFA

niflumic acid

- Nhe3

Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3

- S-M

serosal-to-mucosal

- Pat-1

putative anion transporter-1

Footnotes

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.083.

The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Turnberg LA, Bieberdorf FA, Morawski SG, et al. Interrelationship of chloride, bicarbonate, sodium and hydrogen transport in human ileum. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:557–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI106266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knickelbein R, Aronson PS, Atherton W, et al. Na and Cl transport across rabbit ileal brush border. II. Evidence for Cl:HCO3 exchange and mechanism of coupling. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:G236–G245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.249.2.G236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawenis LR, Stien X, Shull GE, et al. Intestinal NaCl transport in NHE2 and NHE3 knockout mice. Am J Physiol. 2001:G776–G784. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00297.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher MM, Gontarek JC, Bess RS, et al. The Na+/H+ exchange isoform, NHE3, regulates basal canine ileal Na+ absorption in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:174–183. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultheis P, Clarke LL, Meneton P, et al. Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet. 1998;19:282–285. doi: 10.1038/969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan Y, Dong J, Tackett L, et al. NHE2 is the main apical NHE in mouse colonic crypts but an alternative Na+-dependent acid extrusion mechanism is up-regulated in NHE2-null mice. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:G689–G699. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00342.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu HCH, Dong J, Lynch R, et al. Gastrointestinal distribution and kinetic characterization of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 8 (NHE8) Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;21:109–116. doi: 10.1159/000113752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kere J, Lohi H, Hoglund P. Genetic disorders of membrane transport III. Congenital chloride diarrhea. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G7–G13. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moseley RH, Hoglund P, Wu GD, et al. Down-regulated in adenoma gene encodes a chloride transporter defective in congenital chloride diarrhea. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G185–G192. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Shmukler BE, et al. Acute regulation of the SLC26A3 congenital chloride diarrhoea anion exchanger (DRA) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;549.1:3–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Z, Grichtchenko II, Boron WF, et al. Specificity of anion exchange mediated by mouse Slc26a6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33963–33967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, et al. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:F826–F838. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00079.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mount DB, Romero MF. The SLC26 gene family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Pfluegers Arch. 2004;447:710–721. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Friedman DJ, et al. Functional comparison of mouse slc26a6 anion exchanger with human SLC26A6 polypeptide variants: differences in anion selectivity, regulation, and electrogenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8564–8580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shcheynikov N, Wang Y, Park M, et al. Coupling modes and stoichiometry of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by slc26a3 and slc26a6. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:511–524. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang EB, Rao MC. Intestinal water and electrolyte transport. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 2027–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweinfest CW, Spyropoulos DD, Henderson KW, et al. slc26a3 (dra)-deficient mice display chloride-losing diarrhea, enhanced colonic proliferation, and distinct up-regulation of ion transporters in the colon. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37962–37971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, et al. Mouse down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) is an intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is up-regulated in colon of mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22855–22861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZH, Petrovic S, Mann E, et al. Identification of an apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in the small intestine. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:G573–G579. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00338.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke LL, Harline MC. CFTR is required for cAMP inhibition of intestinal Na+ absorption in a cystic fibrosis mouse model. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G259–G267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.2.G259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell DW. Intestinal water and electrolyte transport. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 1267–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liedtke CM, Hopfer U. Mechanism of Cl− translocation across small intestinal brush-border membrane II. Demonstration of Cl−-OH− exchange and Cl− conductance. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:G272–G280. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.3.G272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Wang T, Petrovic S, et al. Renal and intestine transport defects in Slc26a6-null mice. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:C957–C965. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00505.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawenis LR, Boyle KT, Palmer BA, et al. Lateral intercellular space volume as a determinant of CFTR-mediated anion secretion across small intestinal mucosa. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:G1015–G1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00468.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheldon RJ, Malarchik ME, Fox DA, et al. Pharmacological characterization of neural mechanisms regulating mucosal ion transport in mouse jejunum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;249:572–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bukhave K, Rask-Madsen J. Saturation kinetics applied to in vitro effects of low prostaglandin E2 and F2α concentrations on ion transport across human jejunal mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson JE, Gawenis LR, Walker NM, et al. Chloride conductance of CFTR facilitates Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the villous epithelium of intact murine duodenum. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:1241–1251. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00493.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson JE, Schweinfest CW, Shull GE, et al. PAT-1 (Slc26a6) is the predominant apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in the upper villous epithelium of the murine duodenum. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:G1079–G1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00354.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill RK, Borthakur A, Hodges K, et al. Mechanism underlying inhibition of intestinal apical Cl−/OH− exchange following infection with enteropathogenic E coli. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:428–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI29625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alrefai WA, Wen X, Jiang W, et al. Molecular cloning and promoter analysis of downregulated in adenoma (DRA) Am J Physiol. 2007;293:G923–G934. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00029.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donowitz M, Welsh MJ. Regulation of mammalian small intestinal electrolyte secretion. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 1351–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seidler U, Rottinghaus I, Hillesheim J, et al. Sodium and chloride absorptive defects in the small intestine in Slc26a6 null mice. Pflugers Arch. 20087;455:757–766. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0318-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field M, Rao MC, Chang EB. Intestinal water and electrolyte transport and diarrheal disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:800–806. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909213211206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubel KA. Effect of luminal sodium concentration on bicarbonate absorption in rat jejunum. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:3172–3179. doi: 10.1172/JCI107517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turnberg LA, Fordtran JS, Carter NW, et al. Mechanism of bicarbonate absorption and its relationship to sodium transport in the human jejunum. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:548–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI106265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bookstein C, Depaoli AM, Xie Y, et al. Na+/H+ exchangers, NHE-1 and NHE-3, of rat intestine. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:106–113. doi: 10.1172/JCI116933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacob P, Rossmann H, Lamprecht G, et al. Down-regulated in adenoma mediates apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in rabbit, rat, and human duodenum. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:709–724. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barmeyer C, Ye JH, Sidani S, et al. Characteristics of rat down-regulated in adenoma (rDRA) expressed in HEK 293 cells. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaandrager AB, Bot AGM, Ruth P, et al. Differential role of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase II in ion transport in murine small intestine and colon. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:108–114. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko SBH, Shcheynikov N, Choi JY, et al. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J. 2002;21:5662–5672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yun CH, Tse CM, Nath SK, et al. Mammalian Na+/H+ exchanger gene family: structure and function studies. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G1–G11. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffey ME, Devor DC. Intracellular pH and membrane potassium conductance in rabbit distal colon. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C336–C343. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.