Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We aimed to investigate the effect of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE) ε4 on synaptic density in cognitively impaired (CI) participants.

METHODS

One hundred ten CI participants underwent amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F‐florbetapir and synaptic density PET with 18F‐SynVesT‐1. We evaluated the influence of APOE ε4 allele on synaptic density and investigated the effects of ε4 genotype on the associations of synaptic density with Alzheimer's disease (AD) biomarkers. The mediation effects of AD biomarkers on ε4‐associated synaptic density loss were analyzed.

RESULTS

Compared with non‐carriers, APOE ε4 allele carriers exhibited significant synaptic loss in the medial temporal lobe. Amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau pathology mediated the effects of APOE ε4 on synaptic density to different extents. The associations between synaptic density and tau pathology were regulated by the APOE ε4 genotype.

DISCUSSION

The APOE ε4 allele was associated with decreased synaptic density in CI individuals and may be driven by AD biomarkers.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease biomarker, APOE ε4, female risk, hippocampal subfields, synaptic density

1. BACKGROUND

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease (AD) and has been studied extensively. ε4 is known to be associated with abnormalities in the AD biomarkers amyloid beta (Aβ), tau pathology (T), and neurodegeneration (N), known as the “A/T/N” framework. 1 The APOE ε4 allele facilitates the deposition of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and reduces their clearance in the brain. 2 , 3 , 4 Several reports have indicated that APOE ε4 also increases tau pathology in AD. 5 , 6 Among the numerous genetic loci exhibiting sex‐specific effects on AD, the intricate interaction between sex and the APOE allele has been investigated in detail. 7 , 8 However, only a limited number of multiomics studies have been conducted to elucidate the interplay between APOE genotype and sex in AD. 8 Among cognitively impaired (CI) individuals, females are more susceptible to APOE ε4‐associated accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles than males. 9 In opposition to prevailing beliefs, males and females with the APOE ε3/ε4 genotype exhibit nearly equivalent likelihoods of developing AD between the ages of 55 and 85 years, but females exhibit a heightened risk at younger ages. 7 Furthermore, decreased hippocampal volume and glucose uptake are both related to APOE ε4. 10 , 11

However, among these extensively reported findings, the association between the APOE ε4 allele and synaptic function has not been well reported or understood in humans, although this association has been reported in some animal studies, as reviewed in what follows. Synapses have been reported to play a central role in cognitive performance in AD patients. Damage or loss of synapses is significantly related to neurodegeneration. Therefore, synaptic density is considered a key biomarker of neurodegeneration. 12 APOE ε4 has been proposed to aggravate synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. However, this phenomenon has been verified only in animal models and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Mechanistically, APOE ε4 is considered to mediate synaptic dysfunction by interfering with Reelin signaling, which is thought to be a modulator of synaptic strength. 13 APOE ε4 is also associated with synaptic damage to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) at the neurogranin level as well as postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) and synapsin 1 (Syn1) in post mortem human brain tissue. 14 , 15 Cumulative Aβ, which is influenced by the APOE ε4 allele, can also be toxic to synapses. Synapse loss related to Aβ plaques may be caused by the increase in oligomeric Aβ rather than by the Aβ plaque itself. 16 , 17

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: Apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE ε4) is the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, the authors reviewed the literature using PubMed, and their review revealed that the relationship between APOE‐associated synaptic loss and cognitive impairment remains incompletely understood.

Interpretation: APOE ε4 carriers showed a significantly decreased synaptic density compared to non‐carriers, and only one copy of APOE ε4 reduced the synaptic density. This effect was partially mediated by amyloid pathology and fully mediated by tau pathology. APOE ε4 also potentiated the association between synaptic density and tau pathology.

Future directions: This study emphasized the importance of developing genotype‐guided therapies targeting synapses and related protein aggregates in AD. Large sample size and longitudinal data are needed to validate the effect of APOE ε4 on synaptic density loss.

Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) is ubiquitously expressed at synapses in the central nervous system 18 and is specifically localized within synaptic vesicles situated at presynaptic terminals. 19 It is a direct biomarker of synaptic density in vivo. 20 The development of SV2A radioligands, such as 11C‐UCB‐J and 18F‐SynVesT‐1, for positron emission tomography (PET) has provided an opportunity to evaluate synaptic density in the brain in various neurodegenerative disorders. Reduced synaptic density was observed across the hippocampus and neocortex in AD patients by SV2A PET. 21 The hippocampus is considered one of the earliest affected brain regions in AD, and dysfunction of this region is believed to be the core feature of disease‐related memory impairment; moreover, analysis of this subfield could enhance the predictive value of the hippocampus in AD. 22 Furthermore, hippocampal synaptic density has also been assessed for its association with the “A/T/N” biomarkers in AD. Hippocampal synaptic density has a significant correlation with global amyloid deposition in participants with amnestic mild cognitive impairments. 23 Regional synaptic loss follows tau accumulation after 2 years, which indicates that tau spread might drive synaptic vulnerability. 24

As mentioned earlier, several investigations have been performed to explain the influence of the APOE ε4 allele on synaptic density. However, direct evidence about the effect of APOE ε4 on brain synaptic loss is lacking. In this study, we examined the effect of APOE ε4 on synaptic density in individuals with cognitive impairment by using SV2A PET and tested whether APOE ε4 has diverse effects on subfields of the hippocampus. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of APOE ε4 on the associations between synaptic density and AD biomarkers. We hypothesized that APOE ε4 exerts a significant influence on synaptic density throughout the brain, which could be mediated by AD pathology. In addition, we expected a potential interaction between APOE ε4 genotype and sex.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

All participants were aged between 50 and 80 years and were recruited from memory clinics in Shanghai. The exclusion criteria are detailed in the supplementary information. All participants completed comprehensive neuropsychological assessments (described in the supplementary methods), APOE genotyping, 18F‐florbetapir PET/CT (Biograph128.mCT, Siemens, Germany), and 18F‐SynVesT‐1 PET/MR (uPMR790 TOF, United Imaging, China). Seventy‐four participants underwent 18F‐MK6240 PET/CT (Biograph128.mCT; Siemens, Germany) to survey tau pathology in the brain. Assessment of the amyloid PET images was performed through visual inspection by three experienced raters by consensus. 25 All tests and image acquisition were conducted over 1 month.

Patients diagnoses were determined by consensus diagnostic meetings with multiple specialists. The CI participants included individuals with AD dementia and those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). AD was diagnosed according to the 2011 National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer's Association (NIA‐AA) diagnostic criteria after comprehensive neuropsychological assessments. 26 Individuals with MCI were identified using the approach proposed by Jak and Bondi, as described in our previous report. 27 Cognitively unimpaired participants were defined as those who had no cognitive impairment, specifically those who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for AD or MCI, and were excluded from this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of Huashan Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. PET data acquisition and processing

Participants underwent 30‐min 18F‐SynVesT‐1 PET scans at 60 min after injection (6.5 ± 0.65 mCi 18F‐SynVesT‐1) with a 3T uPMR790 TOF (United Imaging Healthcare, China). T1‐weighted images were collected at the same time (repetition time [TR] = 7.2 ms; echo time [TE] = 3.0 ms). For 18F‐florbetapir PET/CT scans, 10 mCi (± 10%) [18F]‐florbetapir was injected, and a 20‐min scan was performed 50 min after the injection. For 18F‐MK6240 PET/CT scans, 5 mCi (± 10%) [18F]‐MK6240 was injected, and a 20‐min scan was performed 90 min after the injection. PET images were reconstructed by the filtered back projection (FBP) algorithm. For each PET imaging tracer, there was one time frame consisting of 30 and 20 min, depending on the tracer used. 18F‐SynVesT‐1 PET attenuation correction was performed using a three‐compartment model (bone, soft tissue, air) attenuation map automatically generated from an ultrashort TE MRI sequence. A low‐dose CT scan was used to perform 18F‐florbetapir and 18F‐MK6240 PET attenuation correction.

SPM12 was used to process the 18F‐florbetapir, 18F‐MK6240, and 18F‐SynVesT‐1 PET images. The detailed preprocessing steps for the voxelwise and region of interest (ROI) analyses are listed in the supplementary information. The cerebellum crus was used as a reference area to calculate the voxelwise standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) of 18F‐florbetapir. 28 Global SUVR values for 18F‐florbetapir were calculated by weighted averaging of the posterior cingulate, precuneus, and temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes, as described in our previous study. 29 The whole cerebellum and inferior cerebellum were used as reference areas to calculate the voxelwise SUVRs of 18F‐SynVesT‐1 and 18F‐MK6240, respectively. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 We chose the ROI for 18F‐SynVesT‐1 PET images in this study according to the findings of a previous study; the ROI encompassed the medial temporal lobe, entorhinal region, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus. 34 The masks of the hippocampal subfields were created by FreeSurfer (Laboratory for Computational Neuroimaging version 6.0, Boston, MA, USA). 35 The hippocampal subfields were further defined as the hippocampal head, hippocampal body, and hippocampal tail, as shown in the supplementary materials (Figure S1). The hippocampal gray matter volume was calculated by CAT12.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Group comparisons between ε4 carriers and ε4 non‐carriers were performed using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the two‐sample T test for continuous variables such as scores on neuropsychological assessments, age, and education years. The voxelwise and ROI‐wise differences in synaptic density among ε4 carriers and ε4 non‐carriers were analyzed by a general linear model (GLM) using SPM12 and SPSS (IBM version 26.0), respectively. Age, sex, and educational level were set as covariates, and a value of p < 0.001 was set as the significance threshold for the voxelwise analysis. Voxelwise analyses were repeated using partial volume‐corrected data.

For ROI‐wise analysis, association coefficients were calculated by partial correlation after adjusting for age, sex, and educational level. Fisher's Z test was used to compare coefficients between ε4 carriers and ε4 non‐carriers. Statistical significance was defined as an unadjusted two‐sided p value less than 0.05. Mediation effects were assessed using the SPSS PROCESS macro (version 3.3). Interaction effects were calculated with the R package stargazer (version 5.2.3).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics

In total, 110 participants, including 63 AD participants and 47 MCI participants, were enrolled in this study. Among the participants, 64 participants were APOE ε4 carriers (54 heterozygotes and 10 homozygotes) and 46 were APOE ε4 non‐carriers (seven individuals with the ε2ε3 genotype and 39 individuals with the ε3ε3 genotype). As shown in Table 1, compared to APOE ε4 non‐carriers, APOE ε4 carriers had a greater frequency of Aβ PET positivity and more global Aβ deposition (51/64 [79.7%] vs 24/46 [52.2%], p = 0.002; global Aβ SUVR: 1.45 ± 0.21 vs 1.38 ± 0.18, p = 0.015). APOE ε4 carriers were younger than APOE ε4 non‐carriers (66.00 ± 8.63 vs 69.63 ± 7.76, p = 0.025). There were no differences in sex ratio, education level, or neuropsychological scores between the APOE ε4 carriers and non‐carriers. Furthermore, there were no differences between the APOE ε4 non‐carriers and carriers among female and male patients separately, except that APOE ε4 carriers had a higher Aβ PET‐positive rate than non‐carriers in the female group (Table S1, 82.5% vs 40.0%, p < 0.001). Compared to participants in the MCI group, the participants in the AD group had greater amyloid deposition, lower education levels, and worse cognitive performance (Table S2).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and neuropsychological testing data for participants.

| Characteristic | APOE ε4 non‐carriers (n = 46) | APOE ε4 carriers (n = 64) | ε4 carriers versus ε4 non‐carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male: female ratio (% female) | 21/25 (54.3%) | 24/40 (62.5%) | p = 0.391 |

| Diagnosis, AD: MCI (% AD) | 24/22 (52.2%) | 39/25 (60.9%) | p = 0.359 |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 69.63 ± 7.76 | 66.00 ± 8.63 | p = 0.025 |

| Educational level (years, mean ± SD) | 10.82 ± 3.74 | 10.83 ± 3.37 | p = 0.985 |

| APOE genotype | |||

| ε2/ε3 | 7 | 0 | |

| ε3/ε3 | 39 | 0 | |

| ε3/ε4 | 0 | 54 | |

| ε4/ε4 | 0 | 10 | |

| MMSE score (mean ± SD) | 21.91 ± 6.52 | 21.11 ± 6.15 | p = 0.511 |

| MoCA‐B score (mean ± SD) | 17.20 ± 7.37 | 15.89 ± 7.34 | p = 0.360 |

| AVLT‐N5 score (mean ± SD) | 1.17 ± 1.58 | 0.72 ± 1.60 | p = 0.197 |

| AVLT‐N7 score (mean ± SD) | 15.64 ± 4.07 | 14.75 ± 4.00 | p = 0.303 |

| BNT score (mean ± SD) | 19.72 ± 5.89 | 17.68 ± 6.33 | p = 0.128 |

| AFT score (mean ± SD) | 8.40 ± 3.96 | 7.68 ± 4.14 | p = 0.376 |

| STT‐A score (mean ± SD) | 117.36 ± 160.03 | 149.82 ± 173.69 | p = 0.371 |

| STT‐B score (mean ± SD) | 311.36 ± 291.70 | 437.27 ± 362.97 | p = 0.070 |

| Global amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition (SUVr ± SD) | 1.38 ± 0.18 | 1.45 ± 0.21 | p = 0.015 |

| Aβ PET positive rate | 24/46 (52.2%) | 51/64 (79.7%) | p = 0.002 |

Abbreviations: AFT, Animal Fluency Test; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; BNT, Boston Naming Test; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MoCA‐B, Montreal Cognitive Assessment‐Basic; STT, Shape Trail Test.

3.2. Effect of APOE on synaptic density

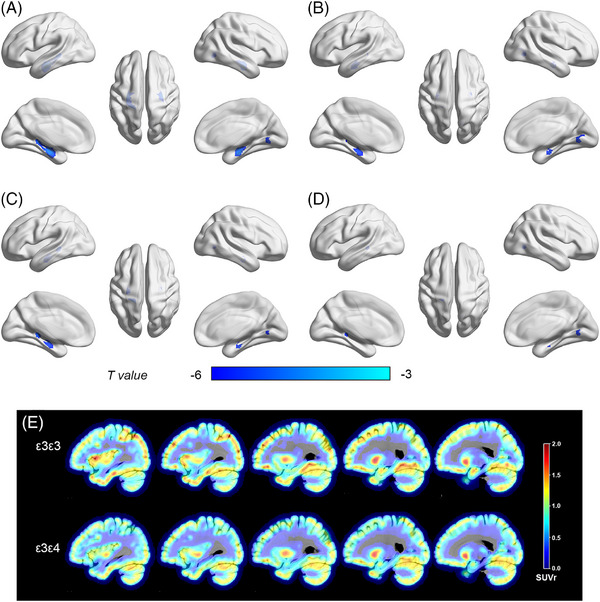

We first investigated the effects of APOE ε4 on regional synaptic density. The APOE ε4 carriers displayed more severe synaptic loss across the medial temporal and occipital cortices than the APOE ε4 non‐carriers (Figure 1A). This trend was retained in the medial temporal and occipital cortices after adjusting for the global florbetapir SUVR (Figure 1B). Furthermore, compared with those with the ε3ε3 genotype, the individuals with the ε3ε4 genotype also exhibited significant synaptic density loss in the medial temporal and occipital cortices (Figure 1C). These differences were retained after adjusting for the global florbetapir SUVR (Figure 1D). The analysis conducted with partial volume correction (PVC) (Figure S2A‐D) yielded similar results as those obtained with non‐PVC.

FIGURE 1.

Impact of APOE ε4 on synaptic density loss. Voxelwise analyses (A–D) corrected to p < 0.001. (A) ε4 non‐carriers versus ε4 carriers without controlling for global cortical amyloid deposition and (B) controlling for global cortical amyloid deposition; (C) ε3ε3 versus ε3ε4 without controlling for global cortical amyloid deposition and (D) controlling for global cortical amyloid deposition. (E) ε3/ε3 and ε3/ε4 participants.

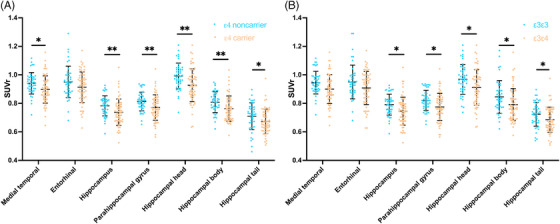

Moreover, we observed an APOE ε4 effect on synaptic loss in the medial temporal (0.90 ± 0.10 vs 0.94 ± 0.07, p = 0.012), hippocampus (0.74 ± 0.09 vs 0.78 ± 0.07, p = 0.004), parahippocampal gyrus (0.77 ± 0.09 vs 0.81 ± 0.07, p = 0.003), hippocampal head (0.93 ± 0.12 vs 0.99 ± 0.09, p = 0.001), hippocampal body (0.76 ± 0.09 vs 0.81 ± 0.07, p = 0.003), and hippocampal tail (0.67 ± 0.09 vs 0.71 ± 0.10, p = 0.011) without controlling for global amyloid burden. After controlling for the amyloid burden, the effect was decreased but still significant in the majority of regions such as in the hippocampus (p = 0.004 vs 0.040), parahippocampal gyrus (p = 0.003 vs 0.031), hippocampal head (p = 0.001 vs 0.014), and hippocampal body (p = 0.003 vs 0.045) (Figure 2A, Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Impact of APOE ε4 on synaptic density loss based on ROI‐wise analysis. (A) ε4 non‐carriers versus ε4 carriers and (B) ε3ε3 versus ε3ε4. P values adjusted for age, education, sex, amyloid β global deposition (Aβ), and clinical diagnosis (diagnosis) are listed in Table 2. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

TABLE 2.

P value adjusted for age, education, sex, amyloid beta (Aβ) global deposition, and clinical diagnosis (diagnosis).

| Groups compared | Regions of interest | p value adjusting for age, education, sex | p value adjusting for age, education, sex, Aβ | p value adjusting for age, education, sex, Aβ, diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε4 non‐carriers versus ε4 carriers | Medial temporal lobe | 0.012 | 0.073 | 0.075 |

| Entorhinal | 0.093 | 0.284 | 0.291 | |

| Hippocampus | 0.004 | 0.040 | 0.041 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 0.003 | 0.031 | 0.032 | |

| Hippocampal head | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.014 | |

| Hippocampal body | 0.003 | 0.045 | 0.046 | |

| Hippocampal tail | 0.011 | 0.081 | 0.081 | |

| ε3ε3 participants versus ε3ε4 participants | Medial temporal lobe | 0.058 | 0.197 | 0.214 |

| Entorhinal | 0.298 | 0.661 | 0.772 | |

| Hippocampus | 0.021 | 0.093 | 0.100 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 0.016 | 0.071 | 0.079 | |

| Hippocampal head | 0.014 | 0.059 | 0.066 | |

| Hippocampal body | 0.021 | 0.101 | 0.106 | |

| Hippocampal tail | 0.013 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

The APOE ε4 effect on synaptic loss was also observed between the individuals with the ε3ε4 genotype and individuals with the ε3ε3 genotype (Figure 2B, Table 2) in the hippocampus (0.74 ± 0.10 vs 0.78 ± 0.07, p = 0.021), parahippocampal gyrus (0.77 ± 0.09 vs 0.82 ± 0.07, p = 0.016), hippocampal head (0.93 ± 0.12 vs 0.99 ± 0.10, p = 0.014), hippocampal body (0.77 ± 0.09 vs 0.81 ± 0.07, p = 0.021), and hippocampal tail (0.68 ± 0.09 vs 0.72 ± 0.09, p = 0.013) without controlling for amyloid. After controlling for the amyloid burden, the effect was also decreased, such as in the hippocampus (p = 0.021 vs .093), parahippocampal gyrus (p = 0.016 vs 0.071), hippocampal head (p = 0.014 vs 0.059), hippocampal body (p = 0.021 vs 0.101), hippocampal tail (p = 0.013 vs 0.051).

3.3. Effect on synaptic density loss in different sex

We observed significant main effects of APOE ε4 on synaptic density based on the ROIs, although no interaction effect was found in any of the ROIs or voxels (Table S3). Sex‐stratified voxelwise analysis revealed that, compared with female APOE ε4 non‐carriers, female APOE ε4 carriers had decreased synaptic density, mainly in the bilateral hippocampus, with both non‐PVC and PVC (Figure S3A‐D). Specifically, ROI‐wise analysis revealed that female APOE ε4 carriers exhibited significant synaptic density loss in the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and hippocampal head, body, and tail (Figure S3G). Compared to male APOE ε4 non‐carriers, male APOE ε4 carriers showed a loss of synaptic density in the medial temporal regions according to voxelwise analyses (Figure S3E) and in the hippocampal head (Figure S3H) without controlling for the global florbetapir SUVr.

3.4. APOE‐stratified effect of association between synaptic density and “A/T/N” biomarkers

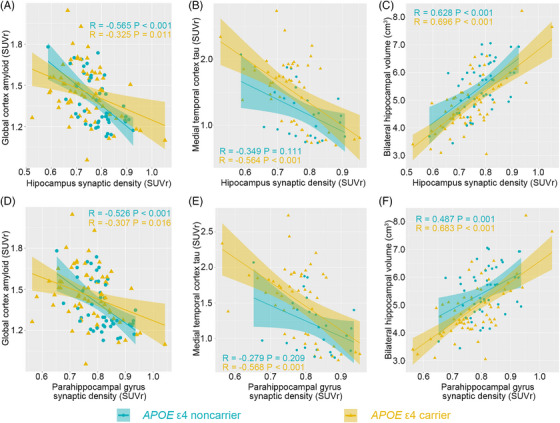

We used partial correlations to investigate the association between synaptic density and “A/T/N” biomarkers while controlling for sex, age, and education level. First, in the overall cohort, we found that hippocampal synaptic density was associated with global amyloid deposition (R = −0.446, p < 0.001), medial temporal tau deposition (R = −0.568, p < 0.001), and hippocampal volume (R = 0.699, p < 0.001). Synaptic density in the parahippocampal gyrus was also associated with global amyloid deposition (R = −0.420, p < 0.001), medial temporal tau deposition (R = −0.554, p < 0.001), and hippocampal volume (R = 0.649, p < 0.001).

According to our stratified analysis, hippocampal synaptic density was negatively associated with global amyloid deposition in APOE ε4 carriers (R = −0.325, p = 0.011) and APOE ε4 non‐carriers (R = −0.565, p < 0.001; Figure 3A). In addition, the synaptic density in the parahippocampal gyrus was associated with global amyloid deposition in APOE ε4 non‐carriers (R = −0.526, p < 0.001) and APOE ε4 carriers (R = −0.307, p = 0.016; Figure 3D). In a subgroup of participants who underwent 18F‐MK6240, we found that medial temporal tau deposition was associated with synaptic density in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus in APOE ε4 carriers (R = −0.564, p < 0.001; Figure 3B; R = −0.568, p < 0.001; Figure 3E) but not in APOE ε4 non‐carriers (R = −0.349, p = 0.111; Figure 3B; R = −0.279, p = 0.209; Figure 3E). Bilateral hippocampal volume was associated with synaptic density in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus in both APOE ε4 carriers (R = 0.696, p < 0.001; Figure 3C; R = 0.683, p < 0.001; Figure 3F) and APOE ε4 non‐carriers (R = 0.628, p < 0.001; Figure 3C; R = 0.487, p = 0.001; Figure 3F).

FIGURE 3.

APOE genotype modifies the association between synaptic density and “A/T/N” biomarkers. APOE genotype modified the association of synaptic density in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus with (A, D) global amyloid deposition, (B, E) medial temporal tau deposition, and (C, F) bilateral hippocampal volume.

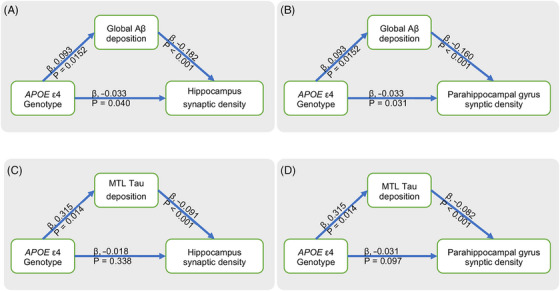

3.5. Synaptic density loss mediated by Aβ and tau pathology

We further performed a mediation analysis to investigate the correlation among APOE ε4 genotype, Aβ (or tau) pathology, and synaptic density in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. We first assessed whether a higher APOE ε4‐conferred Aβ burden was associated with severe synaptic density loss. Bootstrapped mediation analyses revealed that the association between the APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density in the hippocampus or parahippocampal gyrus was partially mediated by the global Aβ PET SUVR (Figure 4A and B, hippocampus: indirect effects = −0.017, SE = 0.008, 95% CI = −0.036 to −0.003; direct effects = −0.033, SE = 0.016, 95% CI = −0.066 to −0.002; parahippocampal gyrus: indirect effects = −0.015, SE = 0.007; 95% CI = −0.031 to −0.003; direct effects = −0.033, SE = 0.015, 95% CI = −0.063 to −0.003). Second, we tested whether the APOE ε4 genotype accelerated decreased synaptic density via increased medial temporal cortex tau PET SUVR accumulation. The relationship between the APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density in the hippocampus (Figure 4C, indirect effects = −0.029, SE = 0.011, 95% CI = −0.052 to −0.008; direct effects = −0.018, SE = 0.019, 95% CI = −0.056 to 0.020) and the parahippocampal gyrus (Figure 4D, indirect effects = −0.026, SE = 0.010, 95% CI = −0.046 to −0.007; direct effects = −0.031, SE = 0.018, 95% CI = −0.067 to 0.006) was fully mediated by the medial temporal tau PET SUVR.

FIGURE 4.

Mediation effects of Aβ/tau pathology on relationship between APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density. (A, B) Mediating effects of global Aβ PET SUVr on association between APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density in hippocampus (indirect effects = −0.017, SE = 0.008, 95% CI = −0.036 to −0.003; direct effects = −0.033, SE = 0.016, 95% CI = −0.066 to −0.002) and parahippocampal gyrus (indirect effects = −0.015, SE = 0.007; 95% CI = −0.031 to −0.003; direct effects = −0.033, SE = 0.015, 95% CI = −0.063 to −0.003). (C, D) Mediating effects of medial temporal cortex tau PET SUVr on relationship between APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density in hippocampus (indirect effects = −0.029, SE = 0.011, 95% CI = −0.052 to −0.008; direct effects = −0.018, SE = 0.019, 95% CI = −0.056 to 0.020) and parahippocampal gyrus (indirect effects = −0.026, SE = 0.010, 95% CI = −0.046 to −0.007; direct effects = −0.031, SE = 0.018, 95% CI = −0.067 to 0.006).

4. DISCUSSION

The APOE ε4 allele was determined to exert different effects on AD biomarkers, such as amyloid and tau deposition. However, the mechanism underlying synaptic loss in APOE ε4 carriers remains unclear. Although various studies have shown that APOE ε4 is associated with impaired synaptic integrity, these observations have not been validated in living human brains. In this study, we found that APOE ε4 was associated with a loss of synaptic density in CI participants. Only one copy of APOE ε4 is sufficient to induce synaptic density loss. However, we did not observe a significant sex–APOE interaction effect on synaptic density. Aβ pathology partially mediated the relationship between the APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density. However, tau pathology fully mediated the relationship between the APOE ε4 genotype and synaptic density.

In this study, we confirmed that APOE ε4 carriers might undergo synaptic damage, which confers additional risk of AD. First, we found that APOE ε4 carriers exhibited significantly reduced synaptic density in the medial temporal lobe and neocortex. The reduced synaptic density remained after controlling for florbetapir SUVR, which may partly explain the synaptic loss associated with the APOE ε4 allele. Some data demonstrate that the soluble amyloid protein is toxic to synapses. 36 , 37 Although evidence indicates that the APOE genotype is associated with synaptic function in animal models, investigations regarding the effect of APOE on synaptic function in humans are limited. To our knowledge, this is the first report of significantly reduced synaptic density in the living human brain.

Previous studies also revealed a significant decrease in synaptic density in the medial temporal lobe and neocortex in patients with AD compared to that in healthy controls. We found that this reduction focused on the medial temporal lobe in APOE ε4 carriers compared to that in APOE ε4 non‐carriers. Synaptic density reduction in the hippocampus is considered the main pathology of AD. Lipidated apoE also regulates neuronal maintenance and repair by regenerating nerve cells to facilitate the repair process after neuronal injury. 38 ApoE4 expressed by neuron could resulted in loss of neurons. 39 Therefore, APOE ε4 could accelerate synaptic impairment, especially hippocampal synaptic impairment. Pathological analysis revealed that in the early stage of AD, the hippocampus experiences a rapid loss of tissue, which is correlated with the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles. 40 Specifically, a reduction in synaptic density in the hippocampal head was significant. A previous tau PET study demonstrated that the earliest tau accumulation occurs in the entorhinal cortex, Brodmann area 35, and anterior hippocampus and could be associated with the loss of synapse density in the hippocampal head. 41 These studies suggested that segmenting the lateral hippocampus into three subregions (head, body, and tail) could be useful for understanding the progressive pathological changes in the hippocampus in AD patients. However, additional studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

The APOE genotype also regulates the association between synaptic density and AD biomarkers. Global amyloid deposition has been associated with hippocampal synaptic density. 42 APOE ε4 potentiated the association between synaptic density and tau pathology. apoE immunoreactivity demonstrated that increased expression of apoE in neurons is associated with increased tau phosphorylation. 43 Tau pathology is closely related to neurodegeneration and cognitive performance. APOE ε4 promotes increased tau deposition and brain atrophy in carriers compared to non‐carriers, which is proposed to be mediated by glia. 44 Astrocytes are the main source of apoE, and signaling by astrocytes results in synaptic and glial transmission. 1 Therefore, we observed a close association between synaptic density and tau deposition and hippocampal volume. In addition, analysis of the mediation model suggested that the effects of APOE ε4 on synaptic loss were not independent and could be driven by amyloid/tau pathology. Amyloid pathology partially mediated the effects of APOE ε4 on synaptic loss and may be correlated with increasing oligomeric Aβ levels rather than Aβ plaques. Importantly, tau pathology in the medial temporal lobe fully mediated the effects of APOE ε4 on synaptic loss, which supports the hypothesis that synapses are damaged due to the toxicity of tau. 45 , 46

This study has several limitations. First, we did not have longitudinal data to validate the effect of APOE ε4 on synaptic density loss. Second, due to the limited resolution of PET, the analysis power of subfields of the hippocampus was limited. Finally, additional studies of cognitively unimpaired patients are needed to investigate the effect of APOE ε4 on synaptic density loss in these individuals.

In this study, we found that APOE ε4 played a significant role in synaptic loss. Compared with non‐carriers, APOE ε4 carriers exhibited significantly decreased synaptic density in the medial temporal lobe, and only one copy of APOE ε4 was sufficient to reduce the synaptic density in the hippocampus. This effect was partially mediated by amyloid pathology and fully mediated by tau pathology. APOE ε4 also potentiated the association between synaptic density and tau pathology. This study emphasized the importance of developing genotype‐guided therapies targeting synapses and related protein aggregates in AD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fang Xie, Yulei Deng, Binyin Li, and Jun Zhao designed this study and coordinated all the research. Fang Xie, Yiyun Henry Huang, and Qihao Guo organized the data collection. Kun He, Jie Wang, Ying Wang, Zhiwen You, Xing Chen, Haijuan Chen, and Junpeng Li collected the data. Kun He and Jie Wang processed and analyzed the data. Yiyun Henry Huang reviewed the study design and revised the study. Fang Xie led the writing of the manuscript, and all the authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

FX is a consultant for Zentera Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

ROLE OF FUNDERS/SPONSORS

The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jianfei Xiao, Xiangqing Xie, Zhiwei Pan, Yue Qian, and Dan Zhou for their assistance. This research was sponsored by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1306305, 2018YFE0203600) and STI2030‐Major project (2022ZD0213800); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81801752, 82171473, 82271441 and 82201583); the startup fund of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (2017QD081); the Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (3030247006); the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2018SHZDZX01); and ZJLab.

He K, Li B, Wang J, et al. APOE ε4 is associated with decreased synaptic density in cognitively impaired participants. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024;20:3157–3166. 10.1002/alz.13775

Institution from which the work originated:

Department of Nuclear Medicine & PET Center, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, No. 518, East Wuzhong Road, Xuhui District, Shanghai, 200040

Kun He, Binyin Li, and Jie Wang contributed equally to this work.

Jun Zhao, Yulei Deng, and Fang Xie shared the corresponding authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1. Koutsodendris N, Nelson MR, Rao A, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer's disease: findings, hypotheses, and potential mechanisms. Annu Rev Pathol. 2022;17:73‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hori Y, Hashimoto T, Nomoto H, Hyman BT, Iwatsubo T. Role of Apolipoprotein E in β‐Amyloidogenesis: isoform‐specific effects on protofibril to fibril conversion of aβ in vitro and brain aβ deposition in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:15163‐15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, et al. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid‐β peptide clearance. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:89ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu CC, Zhao N, Fu Y, et al. ApoE4 accelerates early seeding of amyloid pathology. Neuron. 2017;96:1024‐1032.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baek MS, Cho H, Lee HS, Lee JH, Ryu YH, Lyoo CH. Effect of APOE ε4 genotype on amyloid‐β and tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1). doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00710-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yan S, Zheng C, Paranjpe MD, et al. Sex modifies APOE epsilon4 dose effect on brain tau deposition in cognitively impaired individuals. Brain. 2021;144:3201‐3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for Alzheimer disease: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1178‐1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo L, Zhong MB, Zhang L, Zhang B, Cai D. Sex differences in Alzheimer's disease: insights from the multiomics landscape. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91:61‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu M, Paranjpe MD, Zhou X, et al. Sex modulates the ApoE epsilon4 effect on brain tau deposition measured by (18)F‐AV‐1451 PET in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Theranostics. 2019;9:4959‐4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suh H, Lee YM, Park JM, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in APOE epsilon4 carriers independent of amyloid‐beta (Abeta) burden. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2021;317:111381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reiman EMC, Richard J, Alexander GeneE, et al. Tracking the decline in cerebral glucose metabolism in persons and laboratory animals at genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neurosci Res. 2001;1:194‐206. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colom‐Cadena M, Spires‐Jones T, Zetterberg H, et al. The clinical promise of biomarkers of synapse damage or loss in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y, Durakoglugil MS, Xian X, Herz J. ApoE4 reduces glutamate receptor function and synaptic plasticity by selectively impairing ApoE receptor recycling. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12011‐12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yin J, Reiman EM, Beach TG, et al. Effect of ApoE isoforms on mitochondria in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2020;94:e2404‐e2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun X, Dong C, Levin B, et al. APOE epsilon4 carriers may undergo synaptic damage conferring risk of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1159‐1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koffie RM, Meyer‐Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, et al. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4012‐4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koffie RM, Hashimoto T, Tai HC, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 effects in Alzheimer's disease are mediated by synaptotoxic oligomeric amyloid‐beta. Brain. 2012;135:2155‐2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, DeKosky ST, Mufson EJ. Synaptic alterations in CA1 in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:1501‐1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bajjalieh SM, Peterson K, Linial M, Scheller RH. Brain contains two forms of synaptic vesicle protein 2. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2150‐2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen MK, Mecca AP, Naganawa M, et al. Assessing synaptic density in alzheimer disease with synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A positron emission tomographic imaging. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1215‐1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Wilde MC, Overk CR, Sijben JW. Masliah E. Meta‐analysis of synaptic pathology in Alzheimer's disease reveals selective molecular vesicular machinery vulnerability. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:633‐644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maruszak A, Thuret S. Why looking at the whole hippocampus is not enough‐a critical role for anteroposterior axis, subfield and activation analyses to enhance predictive value of hippocampal changes for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O'Dell RS, Mecca AP, Chen MK, et al. Association of Abeta deposition and regional synaptic density in early Alzheimer's disease: a PET imaging study with [(11)C]UCB‐J. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vanderlinden G, Ceccarini J, Vande Casteele T, et al. Spatial decrease of synaptic density in amnestic mild cognitive impairment follows the tau build‐up pattern. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:4244‐4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ren S, Pan Y, Li J, et al. The necessary of ternary amyloid classification for clinical practice: an alternative to the binary amyloid definition. View. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. A/T/N: an unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87:539‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He K, Li B, Huang L, et al. Positive rate and quantification of amyloid pathology with [(18)F]florbetapir in the urban Chinese population. Eur Radiol. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pan FF, Huang Q, Wang Y, et al. Non‐linear character of plasma amyloid beta over the course of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's continuum. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:832700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sadasivam P, Fang XT, Toyonaga T, et al. Quantification of SV2A binding in rodent brain using [(18)F]SynVesT‐1 and PET imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2021;23:372‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang J, Wang J, Xu X, et al. In vivo synaptic density loss correlates with impaired functional and related structural connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2023;43(6):977‐988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tissot C, Servaes S, Lussier FZ, et al. The association of age‐related and off‐target retention with longitudinal quantification of [(18)F]MK6240 Tau PET in target regions. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:452‐459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gobom J, Benedet AL, Mattsson‐Carlgren N, et al. Antibody‐free measurement of cerebrospinal fluid tau phosphorylation across the Alzheimer's disease continuum. Mol Neurodegener. 2022;17:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mecca AP, Chen MK, O'Dell RS, et al. In vivo measurement of widespread synaptic loss in Alzheimer's disease with SV2A PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:974‐982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iglesias JE, Augustinack JC, Nguyen K, et al. A computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using ex vivo, ultra‐high resolution MRI: application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. Neuroimage. 2015;115:117‐1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spires‐Jones TL, Hyman BT. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2014;82:756‐771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klein WL. Synaptotoxic amyloid‐β oligomers: a molecular basis for the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer's disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(1):S49‐65. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ignatius MJ, Gebicke‐Harter PJ, Skene JH, et al. Expression of apolipoprotein E during nerve degeneration and regeneration. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1125‐1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buttini M, Masliah E, Yu G‐Q, et al. Cellular Source of Apolipoprotein E4 Determines Neuronal Susceptibility to Excitotoxic Injury in Transgenic Mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(2):563–569. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chu LW. Alzheimer's disease: early diagnosis and treatment. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:228‐237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berron D, Vogel JW, Insel PS, et al. Early stages of tau pathology and its associations with functional connectivity, atrophy and memory. Brain. 2021;144:2771‐2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Dell RS, Mecca AP, Chen MK, et al. Association of Aβ deposition and regional synaptic density in early Alzheimer's disease: a PET imaging study with [(11)C]UCB‐J. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Therriault J, Benedet AL, Pascoal TA, et al. APOE ε4 potentiates the relationship between amyloid‐beta and tau pathologies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:5977‐5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hunsberger HC, Pinky PD, Smith W, Suppiramaniam V, Reed MN. The role of APOE4 in Alzheimer's disease: strategies for future therapeutic interventions. Neuronal Signal. 2019;3:NS20180203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ji M, Xie XX, Liu DQ, et al. Hepatitis B core VLP‐based mis‐disordered tau vaccine elicits strong immune response and alleviates cognitive deficits and neuropathology progression in Tau.P301S mouse model of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guerrero‐Muñoz MJ, Gerson J, Castillo‐Carranza DL. Tau oligomers: the toxic player at synapses in Alzheimer's disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Supporting information