NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show detailsNurse-led community care

9.1. Introduction

In this chapter we examine the clinical and cost effectiveness of nurse-led community care and whether extended access to these services is appropriate.

“Community nursing encompasses a diverse range of nurses and support workers who work in the community including district nurses, intermediate care nurses, community matrons and hospital at home nurses”.105 Within this chapter community matrons and community specialist nurses will be referred to as well as community/district nurses.

This chapter firstly evaluates the clinical and cost effectiveness of nurse-led community care including evidence of community matrons as well as community specialist nurses.

A community matron has been described as a “highly experienced senior nurse who works closely with patients (mainly those with serious long term conditions or complex range of conditions) in a community setting to directly provide, plan and organise their care.107 Community Matrons were introduced in 2004 in response to a growing awareness that “Care of patients with multiple long-term conditions has been uncoordinated historically, ad hoc, reactive care with little preventive intervention in the absence of one specific healthcare professional responsible for overall health and social care needs”.41

A community specialist nurse is a senior nurse with specific knowledge and experience in one condition often Heart Failure, COPD, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Diabetes. They may be based in and employed by acute or community trusts and will provide support to GP’s and the district nursing teams in the management of symptoms and exacerbations. Specialist nurses will hold individual caseloads and often visit patients in hospital or at home and write admission avoidance plans with patients. They will often have strong links with the teams in the acute sector.

The increasing incidence of people living with multiple long-term conditions and increasing care costs resulted in government legislation.39,40,42,43 The National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions43 provided a framework that advocated person-centred care in a service that is efficient, supportive and appropriate at every stage from diagnosis to end of life”.99

In this chapter we also examined whether extended access to community nursing/district nursing is more clinically and cost effective than standard access. This focuses on extending and standardising the current provision of the existing services, specifically district nurse teams in light of the move towards a comprehensive 7 day service across the NHS.

The current challenges facing the NHS are well known, and community nursing in all forms could be part of the solution for achieving the goals set out in the Five year forward View: enabling people with increasingly complex levels of health and social care requirements to be able to receive care close to home, have timely and appropriate discharge from hospital and have reduced need for unplanned care.

9.2. Review question: Does community matron or nurse-led care improve outcomes compared to usual care?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

9.3. Clinical evidence

We searched for systematic reviews and randomised trials comparing the effectiveness of community matron/nurse-led interventions with usual care to improve outcomes for patients.

We identified 2 Cochrane reviews evaluating nurse-led interventions compared to usual care.133,142 The reviews were assessed for relevance to the review protocol and methodology and were adapted and updated as part of this systematic review. Data for the studies presented in the Cochrane reviews has been included in the analysis. We have updated the Cochrane reviews with additional randomised controlled trials found from the search.

The Cochrane review133 included RCTs comparing disease management interventions specifically directed at patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) to usual care. The review had 3 interventions: 1) case-management interventions, where patients were intensively monitored by telephone calls and home visits, usually by a specialist nurse; 2) clinic interventions involving follow up in a specialist CHF clinic; 3) multidisciplinary interventions (a holistic approach bridging the gap between hospital admission and discharge home delivered by a team). Only the case-management intervention by a specialist nurse matched our protocol criteria and studies from the other two interventions were excluded. The Cochrane review143 included RCTs evaluating respiratory health care worker programmes for COPD patients. Only those studies from the Cochrane reviews meeting our protocol criteria were included in our evidence review. The Cochrane reviews included only CHF and COPD patients so additional RCTs were included in other populations. Also, RCTs published after the Cochrane reviews were included.

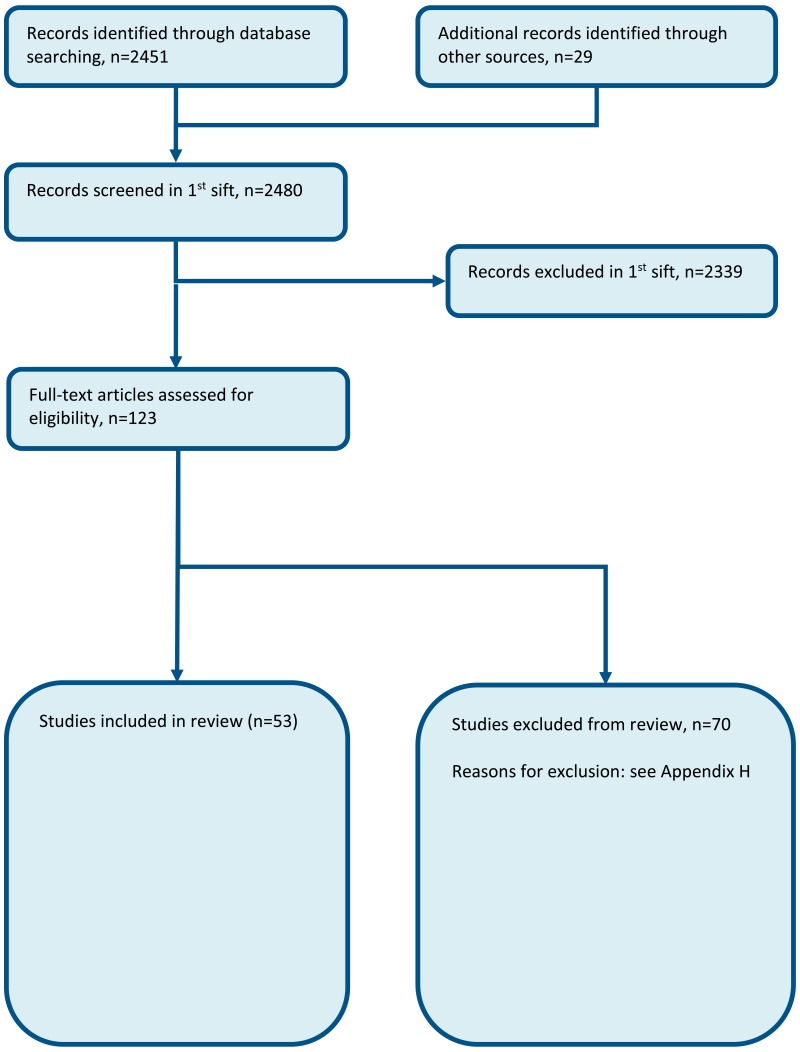

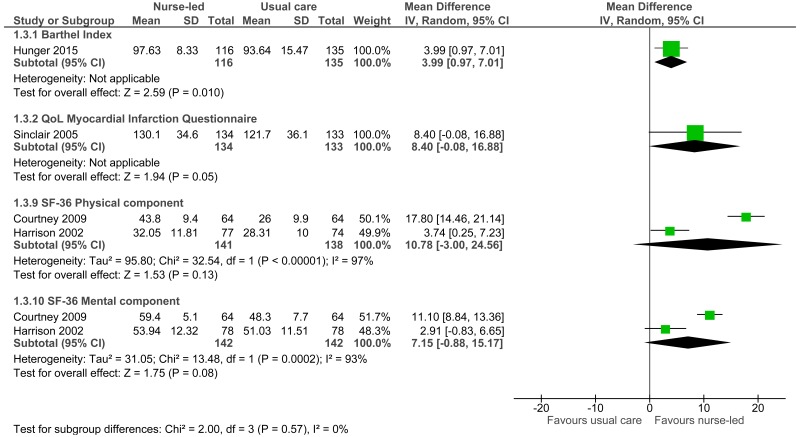

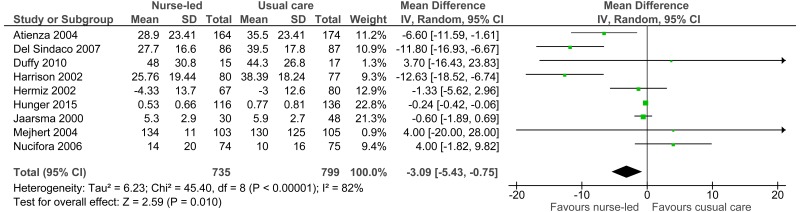

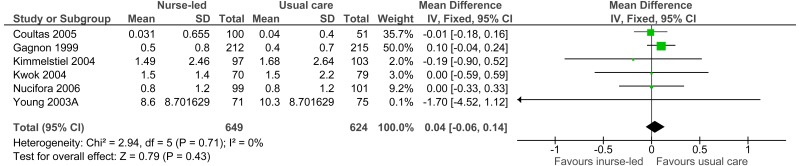

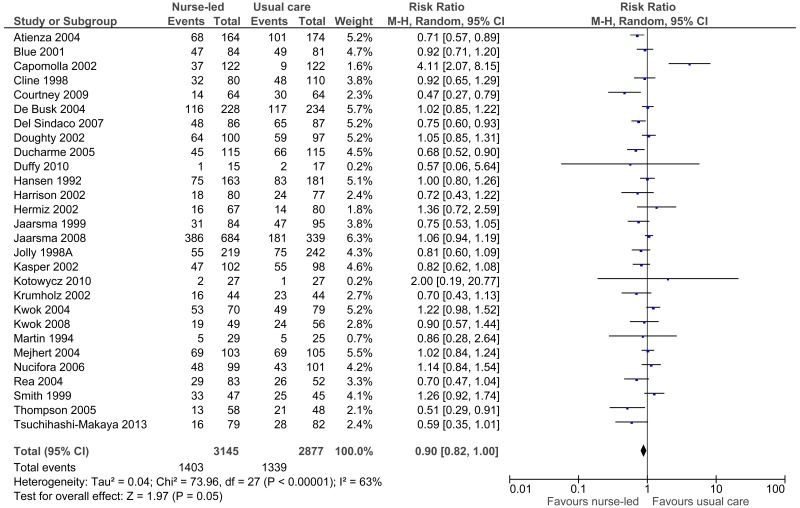

Fifty three studies were included in the review (2 of which were Cochrane reviews); these are summarised in Table 2 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 3). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix D, forest plots in Appendix C, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Clinical evidence profile: Matron/nurse-led care versus usual care.

Narrative findings

Length of stay

Allen 20096 reported the average hospital days for the intervention group (post discharge care management) and control group (stroke unit care only). The study reported a decrease in average hospital days for the control group (post discharge care management: 1.6 days; stroke unit care only: 1.4 days). This study also reported a value for difference in intervention minus control and difference in SD units, 0.2 (0.04).

Latour 200686 reported duration (length of stay) of all emergency readmissions as 11 days (range: 4-59) for the control group and 10.5 (range: 2-68) days for the case management intervention group, but this difference was not statistically significant (95% CI: −13 to 6.0 days).

Martin 199493 reported a median of 0 inpatient days (range 0-14) and 25 inpatient days (range 0-75) for the home treatment group and the control group respectively at 12 weeks follow-up.

In Jaarsma 200870 the median duration of admissions to the hospital because of heart failure in both intervention arms (basic support group: 8.0 days, IQR 4.0-14.0; intensive support group: 9.5 days, IQR 5.0-17.0) was shorter compared with the control group (12.0 days, IQR 5.0-19.5; basic support group versus control, p=0.01; and intensive support versus control, p=0.29).

Quality of life (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure scale)

Allen 20096 reported the average quality of life score for the intervention group (post discharge care management) and control group (stroke unit care only). Stroke Specific-QOL was used as the quality of life measure, the measure has a sum of 49 items with a score range from 49-245; a higher score is better. The study reported a better average quality of life score for the control group (post discharge care management: 196; stroke unit care only: 199). This study also reported a value for difference in intervention minus control and difference in SD units, −2 (−0.07).

Using the Minnesota scale, Doughty 200244 found that the scores at baseline showed markedly impaired quality of life; mean baseline functioning score was 25.6 (SD 12.4) and emotional score 10.0 (SD 7.8). There was a significant improvement in physical functioning from baseline to 12 months between the intervention and control groups (−11.1 and −5.8 respectively, p=0.015). There was no significant change in the emotional score between the 2 groups from baseline to 12 months (−3.3 and −3.3 respectively, p=0.97).

Kasper 200277 found that overall quality of life improved for both groups, but patients in the nurse-led intervention group improved more (change from baseline: mean= −28.3, median −28.0) than the usual care group (change from baseline: mean= −15.7, median −15.0; p=0.001).

9.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

Three economic evaluations were identified with the relevant comparison and have been included in this review.55,112,136 These are summarised in the economic evidence profile below (Table 4) and detailed in the economic evidence tables in Appendix E.

Table 4

Economic evidence profile: Community nurse-led care.

Four economic evaluations relating to this review question were identified but were excluded due to a combination of limited applicability and methodological limitations, and the availability of more applicable evidence.50,51,57,85 These are listed in Appendix H, with reasons for exclusion given.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

9.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

- Seventy-one studies evaluated the role of nurse-led care for improving outcomes compared to usual care provided in the community in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that community matron or nurse-led care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (34 studies, moderate quality), improved quality of life (5 different scores, very low to moderate quality), reduced length of stay (12 studies, moderate quality), improved patient and/or carer satisfaction in studies in which a high score indicated a higher satisfaction (2 studies, high quality) and reduced re-admission (2 studies, low quality). However, the evidence suggested there was no effect for patient and/or carer satisfaction in studies when a low score indicated higher satisfaction (1 study, low quality) and when employing a dissatisfaction score (1 study, very low quality). Dichotomous data suggested a benefit for admission (28 studies, low quality), GP visits (5 studies, very low quality) and ED admissions (8 studies, very low quality) whereas continuous data suggested no difference for admission (6 studies, high quality), GP visits (2 studies, moderate quality) and ED admissions (4 studies, moderate quality).

Economic

- Two cost-utility analyses found that for adults at risk of an AME, community nurse-led care was dominant (less costly and more effective) compared to usual care in the community. Both studies were assessed as partially applicable with minor limitations.

- One cost-utility analysis found that for adults at risk of an AME, community nurse-led care was cost-effective (ICER: £14,900 per QALY gained) compared to usual care in the community. This study was assessed as directly applicable with minor limitations.

9.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Relative values of different outcomes | The Guideline committee considered mortality, avoidable adverse events, patient and/or carer satisfaction and quality of life as critical outcomes for decision making for this review. Other outcomes identified as important for decision making included number of readmissions, number of admissions to hospital after 28 days of first admission, length of hospital stay, number of presentations to the Emergency Department and number of presentations to the GP. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

In assessing the available literature, the committee noted the diversity of models of nurse-led community care, encompassing community nurses, district nurses, specialist nurses, community matrons and hospital-at-home. While ‘nurse-led care’ focuses particularly on interventions delivered before hospital admission or after discharge, it also includes the in-hospital phase (for example, specialist nursing of heart failure patients) and integration of care along the patient pathway. Seventy one studies were included in the review (including studies from 2 Cochrane reviews) comparing nurse-led interventions to usual care. All evaluated the role of nurse-led care for improving outcomes compared to usual care provided in the community for adults at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that nurse-led care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality, improved quality of life, reduced length of stay, improved patient satisfaction (in studies in which a high score indicated higher satisfaction), and reduced re-admission. However, the evidence suggested there was no effect for patient satisfaction in studies when a low score indicated higher satisfaction, or those employing a dissatisfaction score. Dichotomous data suggested a benefit for admission, GP visits and ED admissions whereas continuous data suggested no difference for these outcomes. The committee noted that the evidence included in the review was taken mainly from settings requiring specialist nurse input, for example, CHF and COPD patients, and a benefit was demonstrated in these populations. It was highlighted that all patients with a chronic disease are at risk of AMEs. However, no RCTs were found for other chronic diseases such as nurse-led management of diabetes. As there was sufficient RCT evidence for heart failure, COPD and stroke, no observational studies were included in this review. The committee discussed the generalisability of the evidence and concluded that nurse-led care may be considered beneficial in other clinical conditions. The committee therefore chose to develop a recommendation supporting nurse led care in the community for patients who are at risk of hospital admission or readmission. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

As noted above, the cost of providing nurse-led support in the community will be at least partially offset by hospital cost savings through the prevention of admissions and readmissions. Three economic evaluations were included. They showed that community nurse-led care is cost effective compared to usual care (either dominant (2 studies) or has an incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) less than £20,000 per QALY gained). It is not clear whether these interventions will be cost saving or cost increasing overall and this might depend on the patient cohort as well as the service structure. The committee noted that community nurse specialists, matrons and case managers have condition-specific clinical knowledge as well as knowledge of the individual patient that enables them to provide personalised and effective care. This translates to better outcomes, as is evident from the clinical review. The committee noted that in the evidence reviewed the nurses usually had access to an appropriate specialist physician for advice and support to maximise benefit. Nurse-led care is likely to be provided by a team of nurses with a mixture of levels of experience and grade, as required. |

| Quality of evidence |

The evidence ranged in quality from high to very low due to risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. One economic evaluation was assessed as directly applicable with only minor limitations. The other two also had only minor limitations but they were rated as partially applicable because they were set in Australia and Canada respectively and one of them did not use the EQ-5D. |

| Other considerations |

Nurse-led care can refer to a range of different individuals and tasks, including case managers, community nurses, district nurses, community matrons, hospital-at-home nurses, rapid response nurses and condition-specific community specialist nurses. The roles of these various practitioners are described in the chapter to which this LETR relates. The feature which unites them is their ability to provide patients in the community with interventions which are primarily supportive and educational, focused on increasing independence and enhancing self-management, maintaining optimal function, and thereby reducing the need for hospital admission. Therapeutic interventions include pressure ulcer care, administration of insulin, intravenous antimicrobials, monitoring chronic disease progression and palliative care. Nurses with complementary skill sets work together to support patients with multimorbidity, district and other community nurses provide a direct link to GPs, while condition-specific specialist nurses will provide direct links to hospital specialists and services. While the evidence review highlighted the benefits mostly in established well-defined chronic conditions such as COPD or heart failure, there was some evidence in undifferentiated groups such as frailty, and the committee was of the view that when nurse-led services are well organised, the benefits are likely to apply to people with multimorbidity at risk of, or recovering from, a medical emergency. While all papers included in this review were classified as ‘nurse-led’ care, it was noted that a number of papers that utilised nurse-led care provided it within the context of a multidisciplinary team.21,31,38,44 It is very unlikely for the care to be delivered in isolation by a community nurse; rather care would be delivered as part of multidisciplinary team. The committee noted that there was a substantial overlap between the different models of community care many of which focus on educational and supportive interventions rather than the delivery of clinical care. The committee noted that nurse led care is likely to be most effective when integrated with other services and supported when necessary by specialist nurses (or physicians) with competencies in managing specific conditions. Support should include timely access to physicians and to ancillary services in hospital and in the community such as rehabilitation and occupational therapy, as well as social services. The nurses involved must acquire competencies relevant to this area of practice and have an appropriate professional support structure. Nurse led care should be delivered as part of a strategic and integrated approach to health services along the continuum of social, primary and secondary care.36,61,107,113 Primary care services should include nurse-led care in their development plans to ensure optimal access and use. Regional geography such as rural or urban populations will have an impact on how care is delivered and structured, and may also affect recruitment and retention of appropriately trained staff. The use of electronic communication and remote clinical decision support are likely to be of increasing importance. Ongoing education and development is crucial for retention and recruitment of staff and as higher acuity conditions are likely to be discharged earlier from hospital. As community nurses will usually be working as single individuals, it is important that the ethos of a team is fostered and that each member has the opportunity for group case discussion, observed practice, training and professional development, and reflective learning within a supportive system which enhances retention and recruitment, as reflected in NHS England’s Framework for Commissioning Community Nursing.105 This framework which was published in October 2015 provides a good foundation to inform stakeholders who are responsible for delivery of care in the community. |

Extended access to community nursing

9.7. Review question: Is extended access to community nursing/district nursing more clinically and cost effective than standard access?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 5

PICO characteristics of review question.

9.8. Clinical evidence

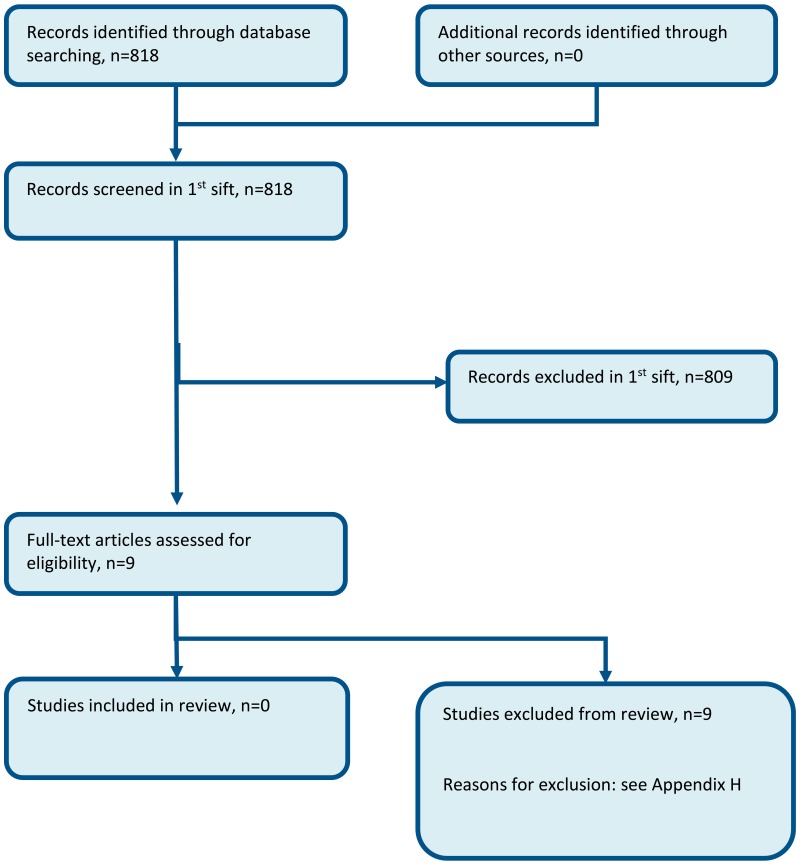

No relevant clinical studies were identified.

9.9. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

9.10. Evidence statements

Clinical

No clinical evidence was identified.

Economic

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

9.11. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendation | - |

| Research recommendations | RR6. What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of providing extended access to community nursing, for example during evenings and weekends? |

| Relative values of different outcomes | The committee considered mortality, avoidable adverse events (for example, sepsis), quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction and presentation to ED as the critical outcomes for decision making. Other important outcomes included length of stay, unplanned hospital admission (ambulatory care conditions), delayed discharge and staff satisfaction. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

No evidence evaluating the effectiveness of extended access to community nursing/district nursing compared with standard access was found. The committee noted that the provision of extended access to community nursing/district nursing may prevent presentation to the ED in certain populations (for example, palliative care), who are likely to have urgent care needs which can be appropriately managed by a community/district nurse. The district nursing educational and career framework published by NHSE in 2015105 outlines the expectation that community nurses will enable early detection of deterioration and prompt escalation to avoid hospital admission. The community nurse is well placed to recognise a change in condition for patients with long tern conditions at risk of AME. It was also considered that the provision of extended access to community nursing/district nursing would be unlikely to prevent presentation to the ED among other populations (for example, those with chest pain). However, there was no research evidence to support or contradict either of these considerations. Therefore, the committee chose not to develop a recommendation given the lack of evidence available. The committee considered the complex range of care delivered by community nurses to patients with a long term condition who are at risk of an AME, and also support provided for post-operative patients (e.g. wound care) and that enhanced access could prevent ED presentation and admissions 7 days week. As there was no evidence to support a positive or negative recommendation, the committee decided to make a research recommendation. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs | No economic evaluations were included. In the absence of evidence, the unit costs of a community nurse and ED visit were presented (Chapter 41 Appendix I). The committee noted that a community nurse visit is substantially cheaper than an ED visit. Extended access to a community nurse might be cost effective or even cost saving if it were to prevent ED presentations without a negative effect on clinical outcomes. However, this needs to be researched. |

| Quality of evidence | No RCT, observational or economic evidence was identified for this question. |

| Other considerations |

The committee noted the complex roles of community nurses in the NHS. The RCN has identified the three care domains for the effective delivery of district nursing services such as:

Standard access to community nursing/district nursing is variable across the country but mostly covers Monday to Friday usually 08:00 – 18:30h. During evenings and weekends staffing is reduced, so the service aims to accommodate the more urgent needs such as facilitating hospital discharge, dressings that require changing daily, support with insulin administration or palliative care. In the event of an urgent care requirement during the evenings and weekends, there is usually an out of hours’ telephone number to call. The committee considered how providing extended access to community nursing/district nursing would change current practice. Standard access to community nursing/district nursing is variable across the UK; therefore, the impact of implementation would differ according to region. In the context of 7 day services in the hospital the likelihood is that access to community/district nursing at weekends becomes more important as there would be an expectation that more patients may be discharged at weekends. It was also highlighted that despite the distinction between patients with urgent care needs that could be appropriately managed by a community/district nurse and those with acute medical emergencies who are likely to require other forms of care, for the average patient, every urgent health problem is an acute medical emergency. Those with less social support are more likely to need extended working as they may not have access to other support networks Enhanced access would mean that patients could be seen by their regular district nurse in response to their clinical needs as opposed to the skeleton service which operates at weekends for only the highest priority patients. This may lead to:

|

References

- 1.

- Point-of-care CRP testing in the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 2016; 54(10):117–120 [PubMed: 27737908]

- 2.

- Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006; 9(1):111–126 [PubMed: 16430351]

- 3.

- Akinci AC, Olgun N. The effectiveness of nurse-led, home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD in Turkey. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2011; 36(4):159–165 [PubMed: 21721397]

- 4.

- Aldamiz-Echevarria IB, Muniz J, Rodriguez-Fernandez JA, Vidan-Martinez L, Silva-Cesar M, Lamelo-Alfonsin F et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of a home care unit intervention to reduce readmission and death rates in patients discharged from hospital following admission for heart failure. Revista Espanola De Cardiologia. 2007; 60(9):914–922 [PubMed: 17915147]

- 5.

- Allen KR, Hazelett S, Jarjoura D, Wickstrom GC, Hua K, Weinhardt J et al. Effectiveness of a postdischarge care management model for stroke and transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2002; 11(2):88–98 [PubMed: 17903862]

- 6.

- Allen K, Hazelett S, Jarjoura D, Hua K, Wright K, Weinhardt J et al. A randomized trial testing the superiority of a postdischarge care management model for stroke survivors. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009; 18(6):443–452 [PMC free article: PMC2802837] [PubMed: 19900646]

- 7.

- Allison TG, Farkouh ME, Smars PA, Evans RW, Squires RW, Gabriel SE et al. Management of coronary risk factors by registered nurses versus usual care in patients with unstable angina pectoris (a chest pain evaluation in the emergency room [CHEER] substudy). American Journal of Cardiology. 2000; 86(2):133–138 [PubMed: 10913471]

- 8.

- Atienza F, Anguita M, Martinez-Alzamora N, Osca J, Ojeda S, Almenar L et al. Multicenter randomized trial of a comprehensive hospital discharge and outpatient heart failure management program. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2004; 6(5):643–652 [PubMed: 15302014]

- 9.

- Bergner M, Hudson LD, Conrad DA, Patmont CM, McDonald GJ, Perrin EB et al. The cost and efficacy of home care for patients with chronic lung disease. Medical Care. 1988; 26(6):566–579 [PubMed: 3379988]

- 10.

- Billington J, Coster S, Murrells T, Norman I. Evaluation of a nurse-led educational telephone intervention to support self-management of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized feasibility study. COPD. 2015; 12(4):395–403 [PubMed: 25474080]

- 11.

- Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, Davie AP, McDonagh TA, Murdoch DR et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001; 323(7315):715–718 [PMC free article: PMC56888] [PubMed: 11576977]

- 12.

- Blue L, McMurray JJ. A specialist nurse-led, home-based intervention in Scotland. BMJ Books. 2001; [PMC free article: PMC56888] [PubMed: 11576977]

- 13.

- Boter H. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of an outreach nursing support program for recently discharged stroke patients. Stroke. a journal of cerebral circulation 2004; 35(12):2867–2872 [PubMed: 15514186]

- 14.

- Bowler M. Exploring patients’ experiences of a community matron service using storybooks. Nursing Times. 2009; 105(24):19–21 [PubMed: 19601436]

- 15.

- Brandon AF, Schuessler JB, Ellison KJ, Lazenby RB. The effects of an advanced practice nurse led telephone intervention on outcomes of patients with heart failure. Applied Nursing Research. 2009; 22(4):e1–e7 [PubMed: 19875032]

- 16.

- Bryant-Lukosius D, Carter N, Reid K, Donald F, Martin-Misener R, Kilpatrick K et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of clinical nurse specialist-led hospital to home transitional care: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2015; 21(5):763–781 [PubMed: 26135524]

- 17.

- Buurman BM, Parlevliet JL, Deelen BA, Haan RJ, Rooij SE. A randomised clinical trial on a comprehensive geriatric assessment and intensive home follow-up after hospital discharge: the Transitional Care Bridge. BMC Health Services Research. 2010; 10:296 [PMC free article: PMC2984496] [PubMed: 21034479]

- 18.

- Campbell JL, Britten N, Green C, Holt TA, Lattimer V, Richards SH et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage of patients requesting same day consultations in general practice: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial comparing nurse-led and GP-led management systems (ESTEEM). Trials. 2013; 14:4 [PMC free article: PMC3574027] [PubMed: 23286331]

- 19.

- Campbell JL, Fletcher E, Britten N, Green C, Holt T, Lattimer V et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage for managing same-day consultation requests in general practice: a cluster randomised controlled trial comparing general practitioner-led and nurse-led management systems with usual care (the ESTEEM trial). Health Technology Assessment. 2015; 19(13):1–212 [PMC free article: PMC4780897] [PubMed: 25690266]

- 20.

- Campbell JL, Fletcher E, Britten N, Green C, Holt TA, Lattimer V et al. Telephone triage for management of same-day consultation requests in general practice (the ESTEEM trial): a cluster-randomised controlled trial and cost-consequence analysis. The Lancet. 2014; 384(9957):1859–1868 [PubMed: 25098487]

- 21.

- Capomolla S, Febo O, Ceresa M, Caporotondi A, Guazzotti G, La Rovere M et al. Cost/utility ratio in chronic heart failure: comparison between heart failure management program delivered by day-hospital and usual care. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002; 40(7):1259–1266 [PubMed: 12383573]

- 22.

- Carrington MJ, Chan YK, Calderone A, Scuffham PA, Esterman A, Goldstein S et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of a nurse-led, home-based intervention for optimal secondary cardiac prevention suggests some benefits for men but not for women: the Young at Heart study. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2013; 6(4):379–389 [PubMed: 23819955]

- 23.

- Carroll DL, Rankin SH, Cooper BA. The effects of a collaborative peer advisor/advanced practice nurse intervention: cardiac rehabilitation participation and rehospitalization in older adults after a cardiac event. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007; 22(4):313–319 [PubMed: 17589284]

- 24.

- Chan YK, Stewart S, Calderone A, Scuffham P, Goldstein S, Carrington MJ et al. Exploring the potential to remain “Young @ Heart”: initial findings of a multi-centre, randomised study of nurse-led, home-based intervention in a hybrid health care system. International Journal of Cardiology. 2012; 154(1):52–58 [PubMed: 20888653]

- 25.

- Chatwin M, Hawkins G, Panicchia L, Woods A, Hanak A, Lucas R et al. Randomised crossover trial of telemonitoring in chronic respiratory patients (TeleCRAFT trial). Thorax. 2016; 71(4):305–311 [PMC free article: PMC4819626] [PubMed: 26962013]

- 26.

- Chau JP, Lee DT, Yu DS, Chow AY, Yu WC, Chair SY et al. A feasibility study to investigate the acceptability and potential effectiveness of a telecare service for older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012; 81(10):674–682 [PubMed: 22789911]

- 27.

- Chew-Graham CA, Lovell K, Roberts C, Baldwin R, Morley M, Burns A et al. A randomised controlled trial to test the feasibility of a collaborative care model for the management of depression in older people. British Journal of General Practice. 2007; 57(538):364–370 [PMC free article: PMC2047010] [PubMed: 17504586]

- 28.

- Chiu WK, Newcomer R. A systematic review of nurse-assisted case management to improve hospital discharge transition outcomes for the elderly. Professional Case Management. 2007; 12(6):330–336 [PubMed: 18030153]

- 29.

- Cline CM, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR. Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart. 1998; 80(5):442–446 [PMC free article: PMC1728835] [PubMed: 9930041]

- 30.

- Cline CM, Iwarson A. Nurse-led clinics for the management of heart failure in Sweden. BMJ Books. 2011;

- 31.

- Coultas D, Frederick J, Barnett B, Singh G, Wludyka P. A randomized trial of two types of nurse-assisted home care for patients with COPD. Chest. 2005; 128(4):2017–2024 [PubMed: 16236850]

- 32.

- Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K, Hamilton K. Fewer emergency readmissions and better quality of life for older adults at risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a 24-week exercise and telephone follow-up program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009; 57(3):395–402 [PubMed: 19245413]

- 33.

- Courtney MD, Edwards HE, Chang AM, Parker AW, Finlayson K, Bradbury C et al. Improved functional ability and independence in activities of daily living for older adults at high risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2012; 18(1):128–134 [PubMed: 21457411]

- 34.

- Dalby DM, Sellors JW, Fraser FD, Fraser C, van Ineveld C, Howard M. Effect of preventive home visits by a nurse on the outcomes of frail elderly people in the community: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000; 162(4):497–500 [PMC free article: PMC1231166] [PubMed: 10701382]

- 35.

- Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Trial of a disease management program to reduce hospital readmissions of the chronically critically ill. Chest. 2005; 128(2):507–517 [PubMed: 16100132]

- 36.

- Damery S, Flanagan S, Combes G. Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2016; 6(11):e011952 [PMC free article: PMC5129137] [PubMed: 27872113]

- 37.

- DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Parker KM, Bandura A, Kraemer HC, Cher DJ et al. Care management for low-risk patients with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004; 141(8):606–613 [PubMed: 15492340]

- 38.

- Del Sindaco D, Pulignano G, Minardi G, Apostoli A, Guerrieri L, Rotoloni M et al. Two-year outcome of a prospective, controlled study of a disease management programme for elderly patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2007; 8(5):324–329 [PubMed: 17443097]

- 39.

- Department of Health. The NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London. The Stationary Office, 2000. Available from: http://webarchive

.nationalarchives .gov.uk/+/www .dh.gov.uk/en /publicationsandstatistics /publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4002960 - 40.

- Department of Health. The NHS Improvement Plan: putting people at the heart of public services. London. The Stationary Office, 2004. Available from: http://webarchive

.nationalarchives .gov.uk/+/www .dh.gov.uk/en /publicationsandstatistics /publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4084476 - 41.

- Department of Health. Supporting people with long term conditions: An NHS and social care model to support local innovation and integration. London. The Stationary Office, 2005. Available from: http://webarchive

.nationalarchives .gov.uk/+/dh .gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics /publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4100252 - 42.

- Department of Health. Supporting people with long term conditions: liberating the talents of nurses who care for people with long term conditions. London. The Stationary Office, 2005. Available from: http://webarchive

.nationalarchives .gov.uk/+/www .dh.gov.uk/en /Publicationsandstatistics /Publications/PublicationsPolicyandGuidance/DH_4102469 - 43.

- Department of Health. The National service framework for long-term conditions. London. The Stationary Office, 2005. Available from: https://www

.gov.uk/government /uploads/system /uploads/attachment_data /file/198114 /National_Service_Framework _for_Long_Term_Conditions.pdf - 44.

- Doughty RN, Wright SP, Pearl A, Walsh HJ, Muncaster S, Whalley GA et al. Randomized, controlled trial of integrated heart failure management: the Auckland Heart Failure Management Study. European Heart Journal. 2002; 23(2):139–146 [PubMed: 11785996]

- 45.

- Doughty RN, Wright SP, Walsh HJ, Muncaster S, Pearl A, Sharpe N. Integrated care for patients with chronic heart failure: the New Zealand experience. BMJ Books. 2001;

- 46.

- Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Chronically critically ill patients: health-related quality of life and resource use after a disease management intervention. American Journal of Critical Care. 2007; 16(5):447–457 [PMC free article: PMC2040111] [PubMed: 17724242]

- 47.

- Ducharme A, Doyon O, White M, Rouleau JL, Brophy JM. Impact of care at a multidisciplinary congestive heart failure clinic: a randomized trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005; 173(1):40–45 [PMC free article: PMC1167811] [PubMed: 15997043]

- 48.

- Duffy JR, Hoskins LM, Dudley-Brown S. Improving outcomes for older adults with heart failure: a randomized trial using a theory-guided nursing intervention. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2010; 25(1):56–64 [PubMed: 19512945]

- 49.

- Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, Sloan J, Colon-Otero G. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: results of a randomized pilot study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012; 15(8):890–895 [PMC free article: PMC3396133] [PubMed: 22559906]

- 50.

- Fletcher K, Mant J. A before and after study of the impact of specialist workers for older people. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009; 15(2):335–340 [PubMed: 19335494]

- 51.

- Gage H, Ting S, Williams P, Drennan V, Goodman C, Iliffe S et al. Nurse-led case management for community dwelling older people: an explorative study of models and costs. Journal of Nursing Management. 2013; 21(1):191–201 [PubMed: 23339509]

- 52.

- Gagnon AJ, Schein C, McVey L, Bergman H. Randomized controlled trial of nurse case management of frail older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999; 47(9):1118–1124 [PubMed: 10484257]

- 53.

- Godwin M, Gadag V, Pike A, Pitcher H, Parsons K, McCrate F et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of an intensive 1-year care management program on measures of health status in independent, community-living old elderly: the Eldercare project. Family Practice. 2016; 33(1):37–41 [PubMed: 26560094]

- 54.

- Goldman LE, Sarkar U, Kessell E, Guzman D, Schneidermann M, Pierluissi E et al. Support from hospital to home for elders: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014; 161(7):472–481 [PubMed: 25285540]

- 55.

- Graves N, Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K. Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to reduce emergency re-admissions to hospital among older patients. PloS One. Australia 2009; 4(10):e7455 [PMC free article: PMC2759083] [PubMed: 19829702]

- 56.

- Griffiths PD, Edwards MH, Forbes A, Harris RL, Ritchie G. Effectiveness of intermediate care in nursing-led in-patient units. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004; Issue 4:CD002214. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002214.pub2 [PubMed: 15495030] [CrossRef]

- 57.

- Hall CJ, Peel NM, Comans TA, Gray LC, Scuffham PA. Can post-acute care programmes for older people reduce overall costs in the health system? A case study using the Australian Transition Care Programme. Health and Social Care in the Community. Australia 2012; 20(1):97–102 [PubMed: 21848852]

- 58.

- Hansen FR, Spedtsberg K, Schroll M. Geriatric follow-up by home visits after discharge from hospital: a randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 1992; 21(6):445–450 [PubMed: 1471584]

- 59.

- Harrison MB, Browne GB, Roberts J, Tugwell P, Gafni A, Graham ID. Quality of life of individuals with heart failure: a randomized trial of the effectiveness of two models of hospital-to-home transition. Medical Care. 2002; 40(4):271–282 [PubMed: 12021683]

- 60.

- Hermiz O, Comino E, Marks G, Daffurn K, Wilson S, Harris M. Randomised controlled trial of home based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ. 2002; 325(7370):938 [PMC free article: PMC130059] [PubMed: 12399344]

- 61.

- Heyeres M, McCalman J, Tsey K, Kinchin I. The complexity of health service integration: a review of reviews. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016; 4:223 [PMC free article: PMC5066319] [PubMed: 27800474]

- 62.

- Hout HP, Jansen AP, Marwijk HW, Pronk M, Frijters DF, Nijpels G. Prevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN05358495]. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2010; 65(7):734–742 [PubMed: 20457579]

- 63.

- Houweling ST, Kleefstra N, Hateren KJ, Groenier KH, Meyboom-de Jong B, Bilo HJ. Can diabetes management be safely transferred to practice nurses in a primary care setting? A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011; 20(9–10):1264–1272 [PubMed: 21401764]

- 64.

- Hunger M, Kirchberger I, Holle R, Seidl H, Kuch B, Wende R et al. Does nurse-based case management for aged myocardial infarction patients improve risk factors, physical functioning and mental health? The KORINNA trial. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2015; 22(4):442–450 [PubMed: 24523431]

- 65.

- Huss A, Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Egger M, Clough-Gorr KM. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008; 63(3):298–307 [PubMed: 18375879]

- 66.

- Inglis S, McLennan S, Dawson A, Birchmore L, Horowitz JD, Wilkinson D et al. A new solution for an old problem? Effects of a nurse-led, multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on readmission and mortality in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004; 19(2):118–127 [PubMed: 15058848]

- 67.

- Ismail SA, Gibbons DC, Gnani S. Reducing inappropriate accident and emergency department attendances: a systematic review of primary care service interventions. British Journal of General Practice. 2013; 63(617):E813–E820 [PMC free article: PMC3839390] [PubMed: 24351497]

- 68.

- Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Huijer Abu-Saad H, Dracup K, Gorgels T, van Ree J et al. Effects of education and support on self-care and resource utilization in patients with heart failure. European Heart Journal. 1999; 20(9):673–682 [PubMed: 10208788]

- 69.

- Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Tan F, Abu-Saad HH, Dracup K, Diederiks J. Self-care and quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure: the effect of a supportive educational intervention. Heart and Lung: Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 2000; 29(5):319–330 [PubMed: 10986526]

- 70.

- Jaarsma T, van der Wal MH, Lesman-Leegte I, Luttik ML, Hogenhuis J, Veeger NJ et al. Effect of moderate or intensive disease management program on outcome in patients with heart failure: Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counseling in Heart Failure (COACH). Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008; 168(3):316–324 [PubMed: 18268174]

- 71.

- Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Mant D. Follow-up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction or angina pectoris: initial results of the SHIP trial. Family Practice. 1998; 15(6):548–555 [PubMed: 10078796]

- 72.

- Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Thompson S, Kinmonth A-L et al. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction and angina. Final results of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). BMJ. 1999; 318(7185):706–711 [PMC free article: PMC27782] [PubMed: 10074017]

- 73.

- Joo JY, Huber DL. An integrative review of nurse-led community-based case management effectiveness. International Nursing Review. 2014; 61(1):14–24 [PubMed: 24218992]

- 74.

- Kadda O, Marvaki C, Panagiotakos D. The role of nursing education after a cardiac event. Health Science Journal. 2012; 6(4):634–646

- 75.

- Kanda M, Ota E, Fukuda H, Miyauchi S, Gilmour S, Kono Y et al. Effectiveness of community-based health services by nurse practitioners: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(6):e006670 [PMC free article: PMC4480018] [PubMed: 26105030]

- 76.

- Karlsson MR, Edner M, Henriksson P, Mejhert M, Persson H, Grut M et al. A nurse-based management program in heart failure patients affects females and persons with cognitive dysfunction most. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005; 58(2):146–153 [PubMed: 16009290]

- 77.

- Kasper EK, Gerstenblith G, Hefter G, van Anden E, Brinker JA, Thiemann DR et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of multidisciplinary care in heart failure outpatients at high risk of hospital readmission. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002; 39(3):471–480 [PubMed: 11823086]

- 78.

- Kimmelstiel C, Levine D, Perry K, Patel AR, Sadaniantz A, Gorham N et al. Randomized, controlled evaluation of short- and long-term benefits of heart failure disease management within a diverse provider network: the SPAN-CHF trial. Circulation Journal. 2004; 110(11):1450–1455 [PubMed: 15313938]

- 79.

- Koh KWL, Wang W, Richards AM, Chan MY, Cheng KKF. Effectiveness of advanced practice nurse-led telehealth on readmissions and health-related outcomes among patients with post-acute myocardial infarction: ALTRA study protocol. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016; 72(6):1357–1367 [PubMed: 26915719]

- 80.

- Kotowycz MA, Cosman TL, Tartaglia C, Afzal R, Syal RP, Natarajan MK. Safety and feasibility of early hospital discharge in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction - a prospective and randomized trial in low-risk primary percutaneous coronary intervention patients (the Safe-Depart Trial). American Heart Journal. 2010; 159(1):117 [PubMed: 20102876]

- 81.

- Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ et al. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002; 39(1):83–89 [PubMed: 11755291]

- 82.

- Kuethe MC, Vaessen-Verberne Anja APH, Elbers RG, van Aalderen W. Nurse versus physician-led care for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013; Issue 2:CD009296. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009296.pub2 [PubMed: 23450599] [CrossRef]

- 83.

- Kwok T, Lee J, Woo J, Lee DT, Griffith S. A randomized controlled trial of a community nurse-supported hospital discharge programme in older patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17(1):109–117 [PubMed: 18088263]

- 84.

- Kwok T, Lum CM, Chan HS, Ma HM, Lee D, Woo J. A randomized, controlled trial of an intensive community nurse-supported discharge program in preventing hospital readmissions of older patients with chronic lung disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(8):1240–1246 [PubMed: 15271109]

- 85.

- Latour CH, Bosmans JE, van Tulder MW, de Vos R, Huyse FJ, de Jonge P et al. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led case management intervention in general medical outpatients compared with usual care: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. Netherlands 2007; 62(3):363–370 [PubMed: 17324688]

- 86.

- Latour CHM, de Vos R, Huyse FJ, de Jonge P, van Gemert LAM, Stalman WAB. Effectiveness of post-discharge case management in general-medical outpatients: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics. 2006; 47(5):421–429 [PubMed: 16959931]

- 87.

- Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005; Issue 2:CD001271. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2 [PubMed: 15846614] [CrossRef]

- 88.

- Leventhal ME, Denhaerynck K, Brunner-LaRocca H, Burnand B, Conca A, Bernasconi AT et al. Swiss Interdisciplinary management programme for heart failure (SWIM-HF): a randomised controlled trial study of an outpatient inter-professional management programme for heart failure patients in Switzerland. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2011; 141(March):w13171 [PubMed: 21384285]

- 89.

- Levy CR, Eilertsen T, Kramer AM, Hutt E. Which clinical indicators and resident characteristics are associated with health care practitioner nursing home visits or hospital transfer for urinary tract infections? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2006; 7(8):493–498 [PubMed: 17027626]

- 90.

- Li X, Xu S, Zhou L, Li R, Wang J. Home-based exercise in older adults recently discharged from the hospital for cardiovascular disease in China: randomized clinical trial. Nursing Research. 2015; 64(4):246–255 [PubMed: 26035669]

- 91.

- Llor C, Cots JM, Hernandez S, Ortega J, Arranz J, Monedero MJ et al. Effectiveness of two types of intervention on antibiotic prescribing in respiratory tract infections in Primary Care in Spain. Happy Audit Study. Atencion Primaria. 2014; 46(9):492–500 [PMC free article: PMC6985636] [PubMed: 24768657]

- 92.

- Luckett T, Davidson PM, Lam L, Phillips J, Currow DC, Agar M. Do community specialist palliative care services that provide home nursing increase rates of home death for people with life-limiting illnesses? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013; 45(2):279–297 [PubMed: 22917710]

- 93.

- Martin F, Oyewole A, Moloney A. A randomized controlled trial of a high support hospital discharge team for elderly people. Age and Ageing. 1994; 23(3):228–234 [PubMed: 8085509]

- 94.

- McCauley KM, Bixby MB, Naylor MD. Advanced practice nurse strategies to improve outcomes and reduce cost in elders with heart failure. Disease Management : DM. 2006; 9(5):302–310 [PubMed: 17044764]

- 95.

- McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, Adler DC, Cooley ME, Jepson C et al. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000; 48(12):1707–1713 [PubMed: 11129765]

- 96.

- Mejhert M, Kahan T, Persson H, Edner M. Limited long term effects of a management programme for heart failure. Heart. 2004; 90(9):1010–1015 [PMC free article: PMC1768467] [PubMed: 15310688]

- 97.

- Melis RJF, van Eijken MIJ, Boon ME, Olde Rikkert MGM, van Achterberg T. Process evaluation of a trial evaluating a multidisciplinary nurse-led home visiting programme for vulnerable older people. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010; 32(11):937–946 [PubMed: 19860600]

- 98.

- Middleton S, Donnelly N, Harris J, Ward J. Nursing intervention after carotid endarterectomy: a randomized trial of Co-ordinated Care Post-Discharge (CCPD). Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005; 52(3):250–261 [PubMed: 16194178]

- 99.

- Mitten RL. Managing a patient with COPD and comorbidities: a case study. Nursing Standard. 2015; 30(13):46–51 [PubMed: 26602679]

- 100.

- Morilla-Herrera JC, Garcia-Mayor S, Martin-Santos FJ, Kaknani Uttumchandani S, Leon Campos A, Caro Bautista J et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness and roles of advanced practice nursing in older people. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2016; 53:290–307 [PubMed: 26542652]

- 101.

- Mussi CM, Ruschel K, de Souza EN, Lopes AN, Trojahn MM, Paraboni CC et al. Home visit improves knowledge, self-care and adhesion in heart failure: randomized clinical trial HELEN-I. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem. 2013; 21:20–28 [PubMed: 23459887]

- 102.

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999; 281(7):613–620 [PubMed: 10029122]

- 103.

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(5):675–684 [PubMed: 15086645]

- 104.

- Naylor MD, McCauley KM. The effects of a discharge planning and home follow-up intervention on elders hospitalized with common medical and surgical cardiac conditions. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 1999; 14(1):44–54 [PubMed: 10533691]

- 105.

- NHS England. Framework for commissioning community nursing, 2015. Available from: https://www

.england.nhs .uk/wp-content/uploads /2015/10/Framework-for-commissioning-community-nursing .pdf - 106.

- Nucifora G, Albanese MC, de Biaggio P, Caliandro D, Gregori D, Goss P et al. Lack of improvement of clinical outcomes by a low-cost, hospital-based heart failure management programme. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2006; 7(8):614–622 [PubMed: 16858241]

- 107.

- Nursing Times. What are community matrons? Introduction to the community matron role. 2009. Available from: https://www

.nursingtimes .net/community-matron/5004049 .article [Last accessed: 30 March 2017] - 108.

- Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S, Aronow HU, Auerbach AD, Black JT et al. Effectiveness of remote patient monitoring after discharge of hospitalized patients with heart failure: the better effectiveness after transition - heart failure (BEAT-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(3):310–318 [PMC free article: PMC4827701] [PubMed: 26857383]

- 109.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Purchasing power parities (PPP), 2007. Available from: http://www

.oecd.org/std/ppp - 110.

- Patrick H, Roberts N, Hutt R, Hewitt P, Connelly J, Oliver D. Evaluation of innovations in nursing practice: report and discussion. British Journal of Nursing. 2006; 15(9):520–523 [PubMed: 16723928]

- 111.

- Plant NA, Kelly PJ, Leeder SR, D’Souza M, Mallitt KA, Usherwood T et al. Coordinated care versus standard care in hospital admissions of people with chronic illness: a randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 2015; 203(1):33–38 [PubMed: 26126565]

- 112.

- Ploeg J, Brazil K, Hutchison B, Kaczorowski J, Dalby DM, Goldsmith CH et al. Effect of preventive primary care outreach on health related quality of life among older adults at risk of functional decline: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. Canada 2010; 340:c1480 [PMC free article: PMC3191725] [PubMed: 20400483]

- 113.

- Powell-Davies G, Williams AM, Larsen K, Perkins D, Roland M, Harris MF. Coordinating primary health care: an analysis of the outcomes of a systematic review. Medical Journal of Australia. 2008; 188:(8 Suppl):S65–S68 [PubMed: 18429740]

- 114.

- Rawl SM, Easton KL, Kwiatkowski S, Zemen D, Burczyk B. Effectiveness of a nurse-managed follow-up program for rehabilitation patients after discharge. Rehabilitation Nursing. 1998; 23(4):204–209 [PubMed: 9832919]

- 115.

- Rea H, McAuley S, Stewart A, Lamont C, Roseman P, Didsbury P. A chronic disease management programme can reduce days in hospital for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Internal Medicine Journal. 2004; 34(11):608–614 [PubMed: 15546454]

- 116.

- Runciman P, Currie CT, Nicol M, Green L, McKay V. Discharge of elderly people from an accident and emergency department: evaluation of health visitor follow-up. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996; 24(4):711–718 [PubMed: 8894888]

- 117.

- Scalvini S, Zanelli E, Volterrani M, Martinelli G, Baratti D, Buscaya O. A pilot study of nurse-led home-based tele-cardiology for patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2004; 10(2):113–117 [PubMed: 15068649]

- 118.

- Schwarz KA, Mion LC, Hudock D, Litman G. Telemonitoring of heart failure patients and their caregivers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008; 23(1):18–26 [PubMed: 18326990]

- 119.

- Scott IA. Preventing the rebound: improving care transition in hospital discharge processes. Australian Health Review. 2010; 34:445–451 [PubMed: 21108906]

- 120.

- Sinclair AJ, Conroy SP, Davies M, Bayer AJ. Post-discharge home-based support for older cardiac patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 2005; 34(4):338–343 [PubMed: 15955757]

- 121.

- Smith B, Appleton S, Adams R, Southcott A, Ruffin R. Home care by outreach nursing for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001; Issue 3:CD000994. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000994 [PubMed: 11686972] [CrossRef]

- 122.

- Smith BJ, Appleton SL, Bennett PW, Roberts GC, Del Fante P, Adams R et al. The effect of a respiratory home nurse intervention in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine. 1999; 29(5):718–725 [PubMed: 10630654]

- 123.

- Smith JR, Mildenhall S, Noble MJ, Shepstone L, Koutantji M, Mugford M et al. The Coping with Asthma Study: a randomised controlled trial of a home based, nurse led psychoeducational intervention for adults at risk of adverse asthma outcomes. Thorax. 2005; 60(12):1003–1011 [PMC free article: PMC1747261] [PubMed: 16055616]

- 124.

- Sridhar M, Taylor R, Dawson S, Roberts NJ, Partridge MR. A nurse led intermediate care package in patients who have been hospitalised with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2008; 63(3):194–200 [PubMed: 17901162]

- 125.

- Steiner A, Walsh B, Pickering RM, Wiles R, Ward J, Brooking JI. Therapeutic nursing or unblocking beds? A randomisedcontrolled trial of a post-acute intermediate care unit. BMJ. 2001; 322(453):459 [PMC free article: PMC26560] [PubMed: 11222419]

- 126.

- Stewart S, Horowitz JD. A specialist nurse-led intervention in Australia. 2001

- 127.

- Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD. Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. The Lancet. 1999; 354(9184):1077–1083 [PubMed: 10509499]

- 128.

- Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998; 158(10):1067–1072 [PubMed: 9605777]

- 129.

- Stewart S, Pearson S, Luke CG, Horowitz JD. Effects of home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and out-of-hospital deaths. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998; 46(2):174–180 [PubMed: 9475445]

- 130.

- Stromberg A, Martensson J, Fridlund B, Levin LA, Karlsson JE, Dahlstrom U. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. European Heart Journal. 2003; 24(11):1014–1023 [PubMed: 12788301]

- 131.

- Stuck AE, Minder CE, Peter-Wuest I, Gillmann G, Egli C, Kesselring A et al. A randomized trial of in-home visits for disability prevention in community-dwelling older people at low and high risk for nursing home admission. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000; 160(7):977–986 [PubMed: 10761963]

- 132.

- Suijker JJ, van Rijn M, Buurman BM, Ter Riet G, Moll van Charante EP, de Rooij SE. Effects of nurse-led multifactorial care to prevent disability in community-living older people: cluster randomized trial. PloS One. 2016; 11(7):e0158714 [PMC free article: PMC4961429] [PubMed: 27459349]

- 133.

- Takeda A, Taylor Stephanie JC, Taylor RS, Khan F, Krum H, Underwood M. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012; Issue 9:CD002752. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002752.pub3 [PubMed: 22972058] [CrossRef]

- 134.

- Thompson DR, Roebuck A, Stewart S. Effects of a nurse-led, clinic and home-based intervention on recurrent hospital use in chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2005; 7(3):377–384 [PubMed: 15718178]

- 135.

- Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Matsuo H, Kakinoki S, Takechi S, Kinugawa S, Tsutsui H. Home-based disease management program to improve psychological status in patients with heart failure in Japan. Circulation Journal. 2013; 77(4):926–933 [PubMed: 23502992]

- 136.

- Turner DA, Paul S, Stone MA, Juarez-Garcia A, Squire I, Khunti K. Cost-effectiveness of a disease management programme for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and heart failure in primary care. Heart. United Kingdom 2008; 94(12):1601–1606 [PubMed: 18450843]

- 137.

- van Rossum E, Frederiks CM, Philipsen H, Portengen K, Wiskerke J, Knipschild P. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people. BMJ. 1993; 307(6895):27–32 [PMC free article: PMC1678489] [PubMed: 8343668]

- 138.

- Verschuur EML, Steyerberg EW, Tilanus HW, Polinder S, Essink-Bot ML, Tran KTC et al. Nurse-led follow-up of patients after oesophageal or gastric cardia cancer surgery: a randomised trial. British Journal of Cancer. 2009; 100(1):70–76 [PMC free article: PMC2634677] [PubMed: 19066612]

- 139.

- Wetzels R, Weel C, Grol R, Wensing M. Family practice nurses supporting self-management in older patients with mild osteoarthritis: a randomized trial. BMC Family Practice. 2008; 9:7 [PMC free article: PMC2235871] [PubMed: 18226255]

- 140.

- Williams H, Blue B, Langlois PF. Do follow-up home visits by military nurses of chronically ill medical patients reduce readmissions? Military Medicine. 1994; 159(2):141–144 [PubMed: 8202242]

- 141.

- Wit R, Dam F, Zandbelt L, Buuren A, Heijden K, Leenhouts G et al. A pain education program for chronic cancer pain patients: follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 1997; 73(1):55–69 [PubMed: 9414057]

- 142.

- Wong C, X, Carson K, V, Smith BJ. Home care by outreach nursing for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012; Issue 4:CD000994. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000994.pub3 [PMC free article: PMC7047940] [PubMed: 22513899] [CrossRef]

- 143.

- Wong C, X, Carson K, V, Smith BJ. Home care by outreach nursing for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012; Issue 4:CD000994. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000994.pub3 [PMC free article: PMC7047940] [PubMed: 22513899] [CrossRef]

- 144.

- Wong FK, Chow S, Chung L, Chang K, Chan T, Lee WM et al. Can home visits help reduce hospital readmissions? Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008; 62(5):585–595 [PubMed: 18489451]

- 145.

- Wood-Baker R, Reid D, Robinson A, Walters EH. Clinical trial of community nurse mentoring to improve self-management in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2012; 7:407–413 [PMC free article: PMC3402057] [PubMed: 22848153]

- 146.

- Wye L, Lasseter G, Percival J, Duncan L, Simmonds B, Purdy S. What works in ‘real life’ to facilitate home deaths and fewer hospital admissions for those at end of life?: results from a realist evaluation of new palliative care services in two English counties. BMC Palliative Care. 2014; 13:37 [PMC free article: PMC4114793] [PubMed: 25075202]

- 147.

- Yeung S. The effects of a transitional care programme using holistic care interventions for Chinese stroke survivors and their care providers: a randomized controlled trial Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Hong Kong); 2012.

- 148.

- Young W, Rewa G, Goodman SG, Jaglal SB, Cash L, Lefkowitz C et al. Evaluation of a community-based inner-city disease management program for postmyocardial infarction patients: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003; 169(9):905–910 [PMC free article: PMC219623] [PubMed: 14581307]

- 149.

- Yuan X, Tao Y, Zhao JP, Liu XS, Xiong WN, Xie JG et al. Long-term efficacy of a rural community-based integrated intervention for prevention and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomized controlled trial in China’s rural areas. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2015; 48(11):1023–1031 [PMC free article: PMC4671529] [PubMed: 26352697]

- 150.

- Zwar NA, Hermiz O, Comino E, Middleton S, Vagholkar S, Xuan W et al. Care of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 2012; 197(7):394–398 [PubMed: 23025736]

- 151.

- Zwar N, Hermiz O, Hasan I, Comino E, Middleton S, Vagholkar S et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of nurse and GP partnership for care of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2008; 8:8 [PMC free article: PMC2442044] [PubMed: 18519003]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocols

Table 6Review protocol: Matron/nurse-led care versus usual care from EVIBASE

| Review question | Alternatives to acute care in hospital |

|---|---|

| Guideline condition and its definition | Acute Medical Emergencies. Definition: A medical emergency can arise in anyone, for example, in people: without a previously diagnosed medical condition, with an acute exacerbation of underlying chronic illness, after surgery, after trauma. |

| Objectives | To determine if wider provision of community-based intermediate care prevents people from staying in hospitals longer than necessary while not impacting on patient and carer outcomes. |

| Review population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME or patients at risk of AME. |

|

Adults (17 years and above). Young people (aged 16-17 years). | |

| Line of therapy not an inclusion criterion. | |

|

Interventions and comparators: generic/class; specific/drug (All interventions will be compared with each other, unless otherwise stated) |

Community matron or Nurse-led care. Hospital-based care/services. Usual Care. |

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Unit of randomisation | Patient. |

| Crossover study | Permitted. |

| Minimum duration of study | Not defined. |

| Population stratification |

Early discharge. Admission avoidance. |

| Reasons for stratification | Each of them targets a separate outcome: early discharge would be primarily aimed at reducing length of stay, while admission avoidance would be primarily aimed at reducing hospital admission. Also, the population would be different as the admission avoidance group could be managed at home for the whole episode of care (they could be cared for at home from the start) while the early discharge group needs to be “stabilised” at hospital first then discharged. |

| Subgroup analyses if there is heterogeneity |

|

| Search criteria |

Databases: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL. Date limits for search: No date limits. Language: English only. |

Table 7Review protocol: Is enhanced community nursing/district nursing more clinically and cost effective than standard access?

| Is extended access to community nursing/district nursing more clinically and cost effective than standard access? | |

|---|---|

| Objective | To determine if enhanced access (evenings and weekends) to community nursing improves outcomes. |

| Rationale | What services would be provided? We have covered community nursing so what extra would they be doing? Extending the access – their presence. This is service availability, access to. Can’t be discharged until seen by nurse for example, on Saturday. |

| Topic code | T3-1C. |

| Population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME. |

| Intervention | Extended access (evenings, weekends) to community nursing (that is, staff trained as nurses working in the community such as, district nurses or community tissue viability nurses). |

| Comparison | Standard access (as defined by the study for example, weekday 9am-5pm) to community nursing. |

| Outcomes |

Patient outcomes; Mortality (CRITICAL) Avoidable adverse events (for example, sepsis) (CRITICAL) Quality of life (CRITICAL) Patient and carer satisfaction/carer burden (CRITICAL) Presentation to ED (CRITICAL) Length of stay (IMPORTANT) Unplanned hospital admission (ambulatory care conditions) (IMPORTANT) Delayed discharge (IMPORTANT) Staff satisfaction (IMPORTANT) |

| Exclusion |

Not looking at chronic disease-specific nurse practitioner (undifferentiated nurses; specialist nurses for example, COPD specialty nurses), community matron. Non-UK studies – same as intermediate care (other healthcare systems very different). |

| Search criteria |

The databases to be searched are: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL. Date limits for search: post. Language: English only. |

| The review strategy | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Analysis |

Data synthesis of RCT data. Meta-analysis where appropriate will be conducted. Studies in the following subgroup populations will be included: Frail elderly. Rural versus urban. In addition, if studies have pre-specified in their protocols that results for any of these subgroup populations will be analysed separately, then they will be included. The methodological quality of each study will be assessed using the Evibase checklist and GRADE. |

Appendix B. Clinical study selection

Figure 1Flow chart of clinical article selection for the review of community matron/nurse-led interventions

Appendix C. Forest plots

C.1. Matron or nurse led care

C.1.1. Matron or nurse-led interventions versus usual care

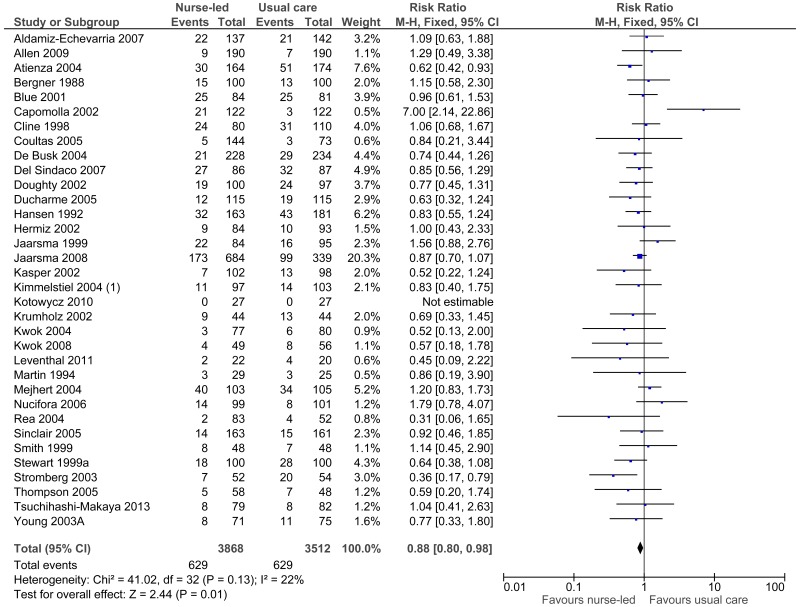

Figure 13Matron/nurse led care versus usual care: Emergency department admissions (dichotomous data)

C.2. Extended access to community nursing

No relevant clinical evidence was retrieved.

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

D.1. Matron or nurse-led care

Cochrane reviews

Download PDF (829K)

Individual studies (not reported in Cochrane reviews)

Download PDF (1.1M)

D.2. Extended access to community nursing

No relevant clinical evidence was retrieved.

Appendix E. Health economic evidence tables

E.1. Matron or nurse-led care

Download PDF (543K)

E.2. Extended access to community services

No economic studies were included.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

F.1. Matron or nurse-led care

Table 8Clinical evidence profile: Matron/nurse-led care versus usual care

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | All interventions | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| All-cause mortality (follow-up 6 weeks - 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 34 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None |

629/3868 (16.3%) |

629/3512 (17.9%) | RR 0.88 (0.8 to 0.98) | 21 fewer per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 36 fewer) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

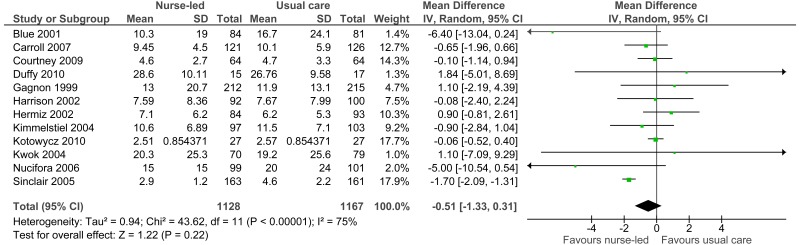

| Length of stay (days) (follow-up 6 weeks - 1 year; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 12 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | serious3 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 1128 | 1167 | - | MD 0.51 lower (1.33 to 0.31 lower) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (high score is good) - Barthel Index (follow-up 1 year; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | 116 | 135 | - | MD 3.99 higher (0.97 to 7.01 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (high score is good) - QoL Myocardial Infarction Questionnaire (follow-up 100 days; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 134 | 133 | - | MD 8.40 higher (0.08 lower to 16.88 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (high score is good) - SF-36 Physical component (follow-up 12-24 weeks; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | 141 | 138 | - | MD 10.78 higher (3 lower to 24.56 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (high score is good) - SF-36 Mental component (follow-up 12-24 weeks; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | 142 | 142 | - | MD 7.15 higher (0.88 lower to 15.17 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Quality of life (high score is bad) (follow-up 60 days - 2 years; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 9 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 735 | 799 | - | MD 3.09 lower (5.43 to 0.75 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Admission (>30 days; continuous data) (follow-up 3-12 months; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 6 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 649 | 624 | - | MD 0.04 higher (0.06 lower to 0.14 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | CRITICAL |

| Admission (>30 days; dichotomous data) (follow-up 6 weeks - 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 28 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None |

1403/3145 (44.6%) |

1339/2877 (46.5%) | RR 0.90 (0.82 to 1) | 47 fewer per 1000 (from 84 fewer to 0 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

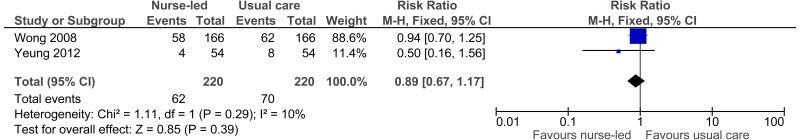

| Re-admission (follow-up 30 days - 1 year) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None |

62/220 (28.2%) |

70/220 (31.8%) | RR 0.89 (0.67 to 1.17) | 35 fewer per 1000 (from 105 fewer to 54 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

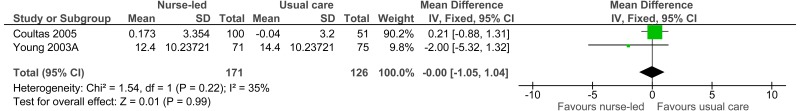

| GP visits (continuous data) (follow-up 6-12 months; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 171 | 126 | - | MD 0 higher (1.05 lower to 1.04 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

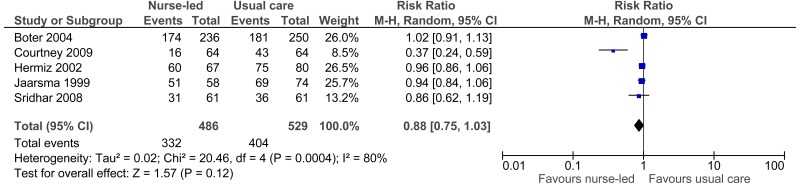

| GP visits (dichotomous data) (follow-up 3-24 months) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None |

332/486 (68.3%) |

404/529 (76.4%) | RR 0.88 (0.75 to 1.03) | 92 fewer per 1000 (from 191 fewer to 23 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

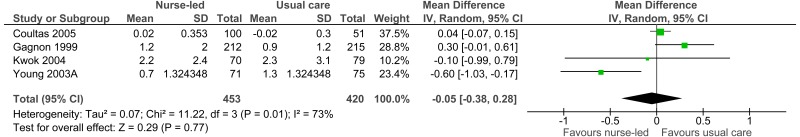

| Emergency department admissions (continuous data) (follow-up 6-12 months; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | serious3 | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 453 | 420 | - | MD 0.05 lower (0.38 lower to 0.28 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

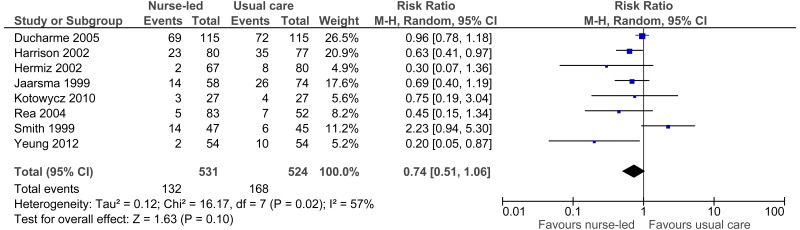

| Emergency department admissions (dichotomous data) (follow-up 4 weeks - 12 months) | ||||||||||||

| 8 | randomised trials | serious1 | serious3 | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None |

132/531 (24.9%) |

168/524 (32.1%) | RR 0.74 (0.51 to 1.06) | 83 fewer per 1000 (from 157 fewer to 19 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

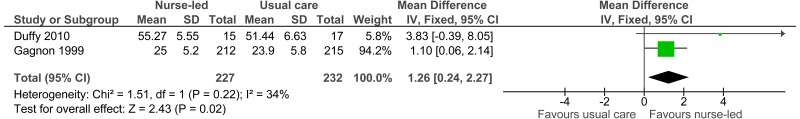

| Patient satisfaction (high score is good) (follow-up 60 days - 10 months; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | no serious risk of bias | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 227 | 232 | - | MD 1.26 higher (0.24 to 2.27 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH | IMPORTANT |

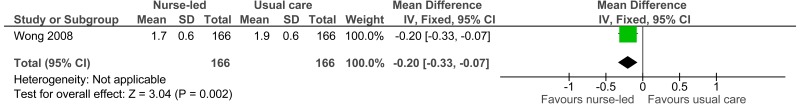

| Patient satisfaction (high score is bad) (follow-up 30 days; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | 166 | 166 | - | MD 0.2 lower (0.33 to 0.07 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

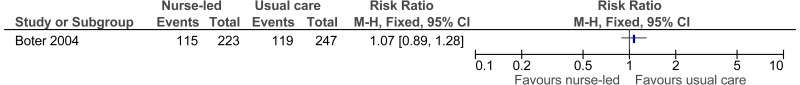

| Patient dissatisfaction; dichotomous data (follow-up 6 months) | ||||||||||||