NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details28. Structured ward rounds

28.1. Introduction

Ward rounds are critical to the smooth flow of the patient journey as they are the key method by which patients in hospital are systematically reviewed by the multidisciplinary team. During a ward round, the current status of each patient is established and the next steps in their care planned. The use of structured ward rounds is recommended by the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Nursing.

Ward rounds are common practice in hospitals across the UK, but they vary in their method, membership and execution. The guideline committee wanted to find out if one method was more effective than others, or if their use has more impact on one patient population over another.

The committee wanted to determine if there was existing evidence to recommend particular practices for effective ward rounds that could be applied to patients with acute medical emergencies.

28.2. Review question: Do structured ward rounds improve processes and outcomes?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

28.3. Clinical evidence

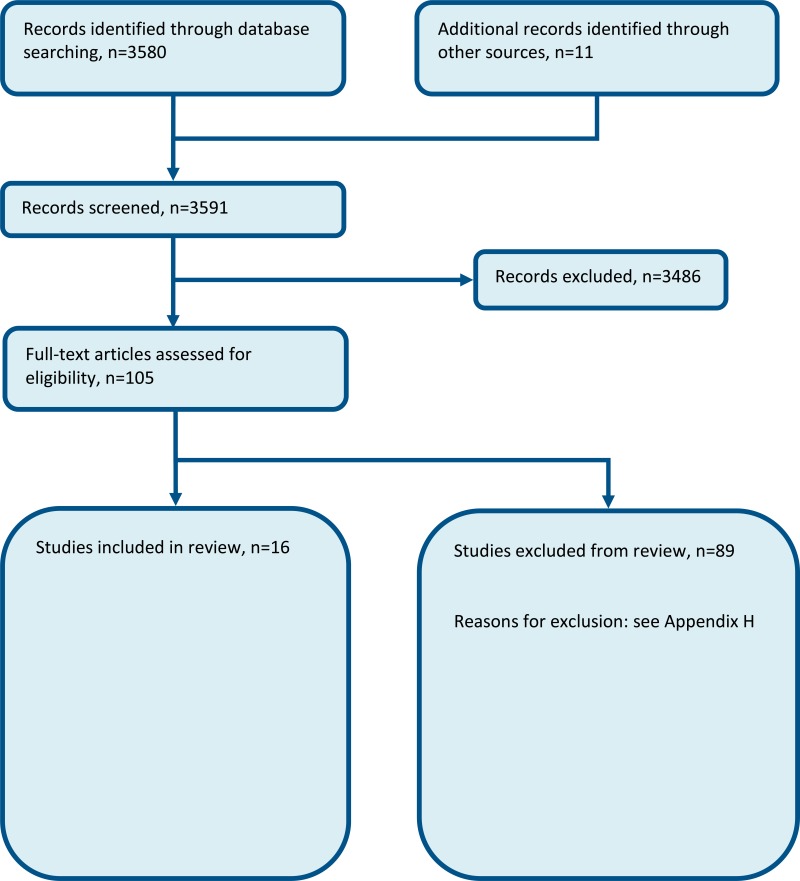

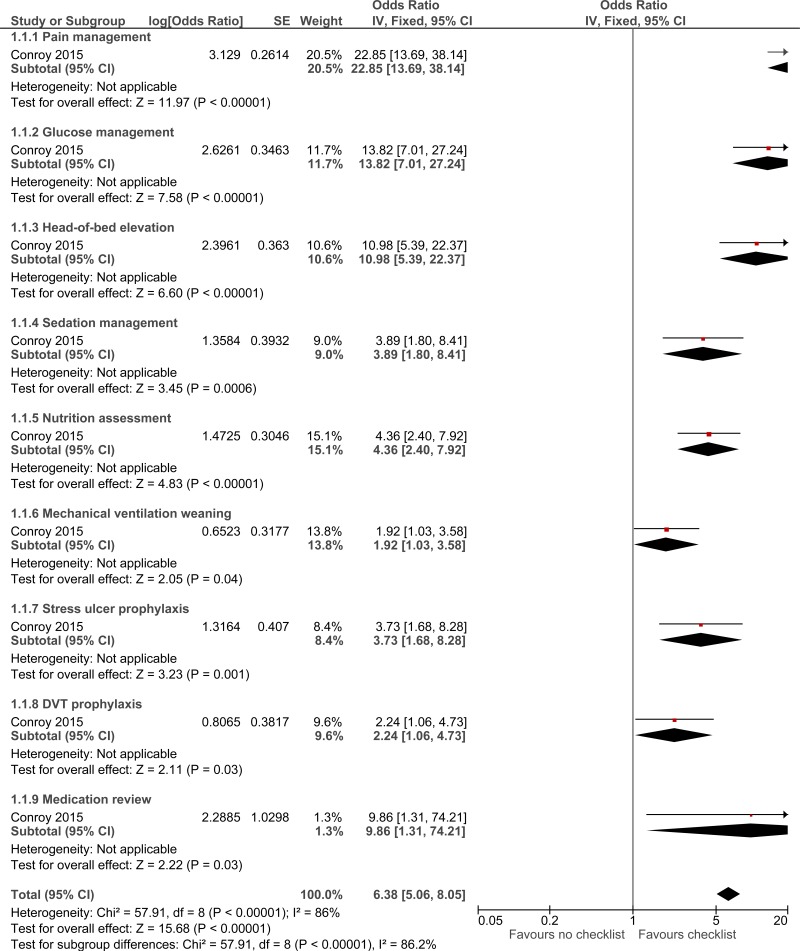

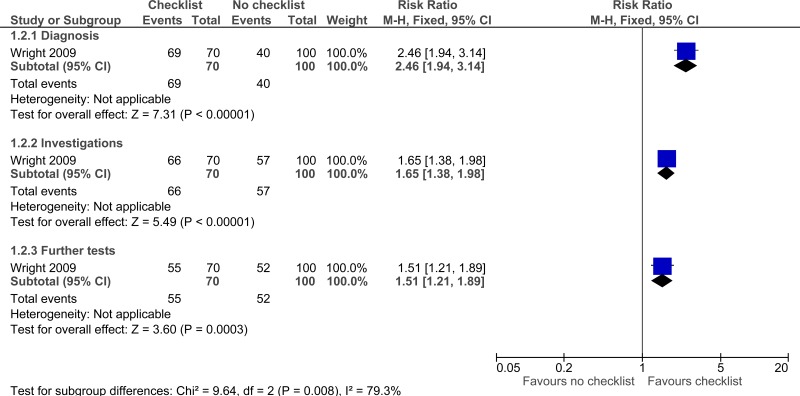

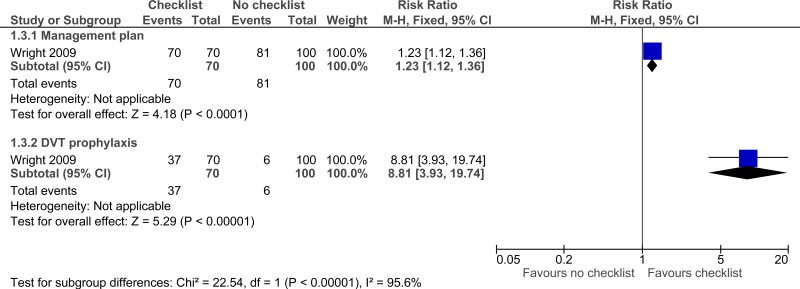

Sixteen studies were included in the review; 2 RCTs, 2 prospective cohort studies, 9 before-after studies, and 3 non-randomised comparative studies;4,11,13,19,26,29,57,62,64–66,83,84,86,88,90 these are summarised in Table 2 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summary below (Table 3;Table 4;Table 5;Table 6;Table 7). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, forest plots in Appendix C, study evidence tables in Appendix D, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Clinical evidence summary: Checklist versus no checklist.

Table 4

Clinical evidence summary: Daily rounding checklist-prompted versus daily rounding checklist-unprompted.

Table 5

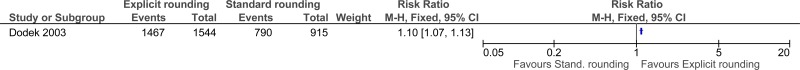

Clinical evidence summary: Explicit rounding approach versus standard rounding approach.

Table 6

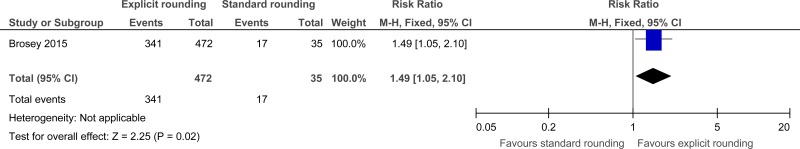

Clinical evidence summary: Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds versus standard physician-centred rounds.

Table 7

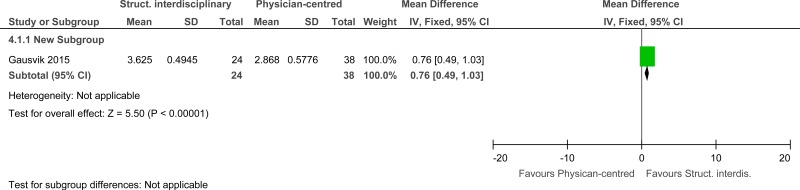

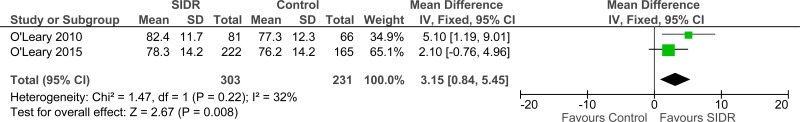

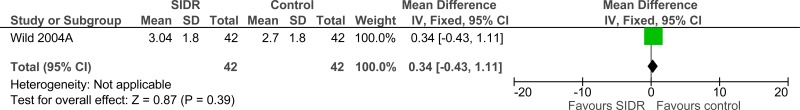

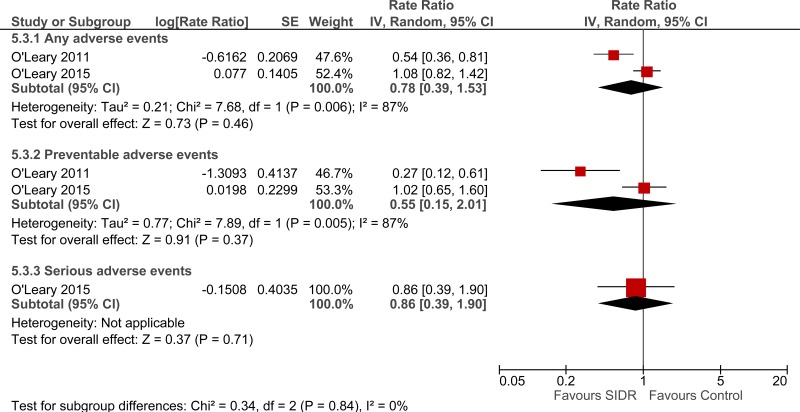

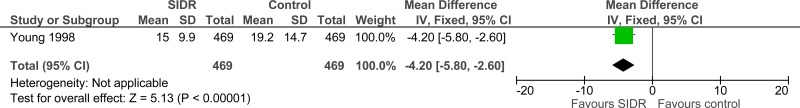

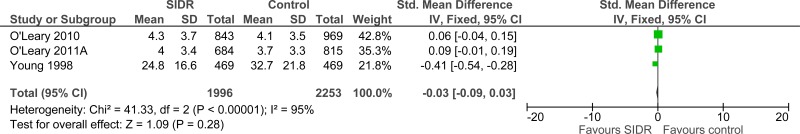

Clinical evidence summary: Structured interdisciplinary rounds (SIDR) versus control (unknown).

Narrative data

Length of stay

One before-and-after study found that the average length of stay for all patients managed on a coaching model of structured, interdisciplinary team rounds was 4.23 days compared to 4.71 days (p=0.029) for patients managed on the unit before the introduction of this rounding model4.

Another before-and-after study found that a daily goals worksheet shortened the length of stay of patients in the intensive care unit (mean 4.3 days, SD 0.63 days) compared to not using a daily goals worksheet (mean 6.4 days, SD 2.5 days) previously.57

ICU length of stay

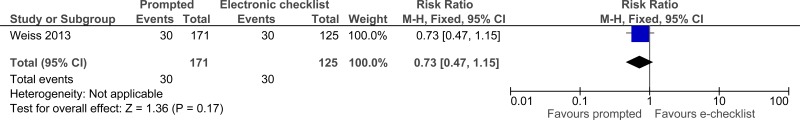

One randomised controlled trial found that there was no difference in median for the length of stay of patients in the intensive care unit between prompted and electronic checklist groups (2.6 [1.5-6.9] days versus 2.8 [1.7-6.5] days).83

Hospital length of stay

One randomised controlled trial found that there was a difference in median for length of stay of patients in hospital between prompted and electronic checklist groups (11.8 [5.9-22.8] days versus 9.6 [5.9-15.8] days).83

Staff satisfaction

A comparative study found that nurses’ ratings of teamwork climate was higher on a hospitalist unit where structured interdisciplinary rounds were used (median 85.7, interquartile range 75.0-92.9) compared to a control hospitalist unit (median 61.6, interquartile range 48.2-83.9; p=0.008).66

28.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

In the absence of health economic evidence, unit costs were presented to the committee – see Chapter 41 Appendix I.

28.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

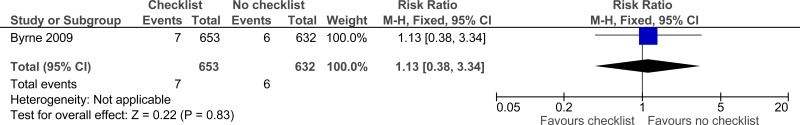

Check lists versus no check-lists

Three studies comprising 2649 people evaluated check-lists to improve processes and outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that check-lists may provide a benefit in adherence to care (2 studies reported separately, very low quality). The evidence suggested there was no effect on mortality (1 study, very low quality).

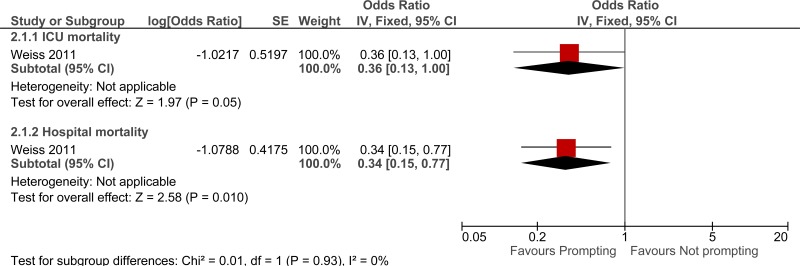

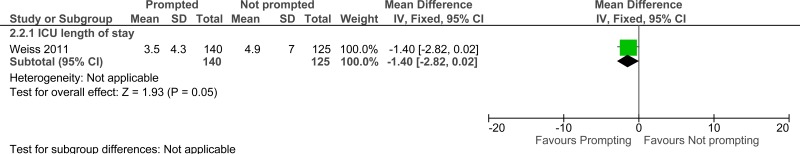

Daily rounding checklist-prompted versus daily rounding checklist -unprompted

One study comprising 296 people evaluated daily rounding checklist- prompted to improve processes and outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that daily rounding checklist- prompted may provide a benefit in reduced ICU length of stay, ICU mortality and hospital mortality (very low quality).

Explicit rounding approach versus standard rounding approach

Two studies comprising 2966 people evaluated explicit rounding approach to improve processes and outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that explicit rounding approach may provide a benefit in improved patient satisfaction (1 study, very low quality) and staff satisfaction (1 study, very low quality).

Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds versus standard physician centred rounds

One study comprising 62 people evaluated structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds to improve processes and outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds had no effect on job satisfaction (very low quality).

Structured interdisciplinary rounds versus control

Four studies comprising 4333 people evaluated structured interdisciplinary rounds to improve processes and outcomes in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested structured interdisciplinary rounds may provide a benefit in improved staff satisfaction (2 studies, very low quality), adverse events (2 studies, very low quality) and reduced ICU length of stay (1 study, very low quality). The evidence suggested there was no difference on length of hospital stay (3 studies, very low quality), length of stay - unadjusted RCT (1 study, low quality) and adverse events (2 studies, very low quality).

Economic

- No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

28.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendation | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes | The committee considered mortality, avoidable adverse events, length of stay/time to discharge, quality of life and patient and/or carer satisfaction to be critical outcomes. Missed or delayed investigations, missed or delayed treatments and staff satisfaction were considered to be important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

Sixteen studies were included in the review, 2 randomised controlled trials and 14 observational studies. There was a variety of interventions used to provide structure to the ward round. The evidence was presented across separate intervention types: Use of checklist versus no checklist The intervention for these studies involved the use of either a paper checklist/worksheet or electronic checklist. Outcomes were measured prior to implementation of the checklist and compared with results after the use of a checklist/worksheet. The evidence suggested that checklists may provide a benefit in adherence to care (a surrogate for missed or delayed treatments). The evidence suggested there was no effect on mortality. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patients and/or carer satisfaction, length of stay and staff satisfaction. Daily rounding check-list -prompted versus daily rounding check-list unprompted The intervention for these studies consisted of a non-care providing or resident physician prompting the rounding team with questions about patients’ conditions in order to aid the ward round. This intervention was carried out in an ICU. The evidence suggested that daily rounding checklist-prompted may provide a benefit in reduced ICU length of stay, ICU mortality and hospital mortality. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, missed or delayed investigations and staff satisfaction. Explicit rounding versus standard rounding These interventions involved using a flow chart demonstrating the ideal ICU ward round and how the processes that make up the ward round should be delivered for example, morning handover or bedside presentations. Actions were discussed in a team meeting. The evidence suggested that explicit rounding may provide a benefit in improved patient and staff satisfaction. No evidence was identified for mortality, avoidable adverse events, quality of life, carer satisfaction, length of stay/time of discharge, missed or delayed investigations, missed or delayed treatments and staff satisfaction. Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounding (SIBR) versus standard physician-centred rounding The intervention in this study consisted of a ward round involving all health and social care staff involved in the patient care including doctors, nurses, pharmacist, social worker and case manager. The SIBR was patient-and-family centred and this was compared with the standard physician-centric rounding. The evidence suggested SIBR had no effect on job satisfaction. No evidence was identified for mortality, avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, length of stay/time of discharge, missed or delayed investigations and missed or delayed treatments. Structured interdisciplinary rounding (SIDR) versus control (unknown) The intervention for these studies consisted of the use of an interdisciplinary team (including a consultant, nurse, social worker, pharmacist and case manager) for ward rounds. Three of the included studies for this comparison were before-and-after studies comparing outcomes prior to implementation of the intervention. The evidence suggested that SIDR may provide a benefit in improved staff satisfaction, adverse events (any) and reduced ICU length of stay. The evidence suggested there was no difference for hospital length of stay, length of stay (from unadjusted RCT) and adverse events. No evidence was identified for mortality, quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, missed or delayed investigations and missed or delayed treatments. The committee felt that the evidence showed a benefit for structured ward rounds and made a recommendation for their use. The ward round is the key driver in the progression and management of patients. Although a routine part of clinical practice, rounds are nevertheless a complex intervention involving many components and multiple points for communication and data exchange, particularly for patients with complex conditions and multi-morbidity. It was felt that providing structure to the ward round would ensure that all aspects of care are delivered and this should result in better outcomes. The committee recommended that a checklist could be used as an option as there was some evidence of benefit. However, the committee recognised that checklists could also be a constraint and might add delays to an otherwise efficient process, particularly if they attempted to be too comprehensive, or inhibited the use of heuristics by experienced staff. For example, the care of low-complexity patients should not be delayed by completion of a checklist with redundant items. They should therefore be used as practice aids, not as rigid tools, to ensure harmonisation of best practice, promoting more reliable care throughout the whole patient pathway, reducing error, promoting timely discharge and minimising readmissions. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

No economic studies were identified. Unit costs of staff (Chapter 41 Appendix I) reported in the evidence were provided to aid consideration of cost effectiveness, although it was unclear from the evidence whether more or less staff time would be required. Interventions using structured ward round checklists and daily charts are unlikely to be resource-intensive compared with unstructured ward rounds. The main costs associated with these interventions are the initial implementation costs including staff training and designing and changing checklists and charts. For electronic checklists, this could include the cost of the devices and servers to store data. These costs are not standardised and would vary across trusts. Studies included in the evidence review show that these interventions may reduce the time taken to record and retrieve notes and could therefore potentially be cost saving. On-going training for new and existing staff must also be considered, as there will be a need to continually develop the checklist as processes change or evolve. Some studies also looked at interventions that would include changes to staffing and staff time. Major changes in staffing involved in ward rounds may lead to an increase in costs and uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. However, there is more likely to be a reallocation staff time, rather than the cost of additional staffing. A few of the studies suggested that length of hospital or ICU stay could be reduced. This would at least partially offset any increased costs. The committee concluded that structured ward rounds were

|

| Quality of evidence |

Fourteen observational studies and 2 randomised controlled trials were included. Nine of the observational studies were before-and-after studies. One of the randomised controlled trials was very low quality (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). The other RCT was low quality (downgraded due to risk of bias). The 14 observational studies were very low quality; reasons for downgrading included risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency and indirectness of outcomes. Some studies reported adherence to care, which was used as a surrogate outcome for missed or delayed treatments but downgraded for indirectness. Much of the positive evidence came from ICU ward rounds where the nursing and medical staff to patient ratio is high, the patients have high acuity, direct communication with patients may be impaired, and decision-making involves consultation with families. However, the committee felt that the evidence could be extrapolated and the principles could be adapted for medical wards. There were no economic studies included in the review. |

| Other considerations |

The committee agreed that a standardised checklist could be incorporated in structured ward rounds, but the format and the way in which such lists might be used should be determined by local experience, and preferably following a gap analysis to determine maximal opportunities for process improvement. The committee noted that the studies comparing prompting to non-prompting had done so as an adjunct to a checklist. The committee commented that other ‘tools’ for a structured ward round could include prompting: one way to achieve this in practice without employing a ‘prompter’ would be to ensure that all members of the team were focused on the task in hand, and were empowered to offer reminders. The committee recognised that introducing structured ward round models/tools effectively in routine practice would likely involve a change in attitudes and behaviours amongst clinical staff, including explicit support from senior staff, a willingness to adopt greater standardisation of processes amongst team members, and a flattening of hierarchies. A checklist on its own will not achieve much;10,25 conversely, once the value of a checklist as a decision-support tool has been recognised and incorporated in practice, the need to ‘tick off’ every component becomes superfluous, and indeed might even be counter-productive. |

References

- 1.

- ‘Daily rounding’ checklist improves ICU compliance. Hospital Peer Review. 2008; 33(4):56–57 [PubMed: 18689085]

- 2.

- Al-Mahrouqi H, Oumer R, Tapper R, Roberts R. Post-acute surgical ward round proforma improves documentation. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. 2013; 2(1) [PMC free article: PMC4652723] [PubMed: 26734192]

- 3.

- Alamri Y, Frizelle F, Al-Mahrouqi H, Eglinton T, Roberts R. Surgical ward round checklist: does it improve medical documentation? A clinical review of Christchurch general surgical notes. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2016; 86(11):878–882 [PubMed: 26749392]

- 4.

- Artenstein AW, Higgins TL, Seiler A, Meyer D, Knee AB, Boynton G et al. Promoting high value inpatient care via a coaching model of structured, interdisciplinary team rounds. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015; 76(1):41–45 [PubMed: 25585183]

- 5.

- Aung TH, Judith Beck A, Siese T, Berrisford R. Less is more: a project to reduce the number of PIMs (potentially inappropriate medications) on an elderly care ward. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. 2016; 5(1):w4260 [PMC free article: PMC4822020] [PubMed: 27096089]

- 6.

- Baba J, Thompson MR, Berger RG. Rounds reports: early experiences of using printed summaries of electronic medical records in a large teaching medical hospital. Health Informatics Journal. 2011; 17(1):15–23 [PubMed: 25133766]

- 7.

- Bhamidipati VS, Elliott DJ, Justice EM, Belleh E, Sonnad SS, Robinson EJ. Structure and outcomes of interdisciplinary rounds in hospitalized medicine patients: a systematic review and suggested taxonomy. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2016; 11(7):513–523 [PubMed: 26991337]

- 8.

- Blucher KM, Dal Pra SE, Hogan J, Wysocki AP. Ward safety checklist in the acute surgical unit. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2014; 84(10):745–747 [PubMed: 24341940]

- 9.

- Boland X. Implementation of a ward round pro-forma to improve adherence to best practice guidelines. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. 2015; 4(1) [PMC free article: PMC4645828] [PubMed: 26734332]

- 10.

- Bosk CL, Dixon-Woods M, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Reality check for checklists. The Lancet. 2009; 374(9688):444–445 [PubMed: 19681190]

- 11.

- Brosey LA, March KS. Effectiveness of structured hourly nurse rounding on patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2015; 30(2):153–159 [PubMed: 25237791]

- 12.

- Butcher BW, Vittinghoff E, Maselli J, Auerbach AD. Impact of proactive rounding by a rapid response team on patient outcomes at an academic medical center. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2013; 8(1):7–12 [PMC free article: PMC3538927] [PubMed: 23024019]

- 13.

- Byrnes MC, Schuerer DJ, Schallom ME, Sona CS, Mazuski JE, Taylor BE et al. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Critical Care Medicine. 2009; 37(10):2775–2781 [PubMed: 19581803]

- 14.

- Calder LA, Kwok ESH, Adam Cwinn A, Worthington J, Yelle JD, Waggott M et al. Enhancing the quality of morbidity and mortality rounds: the Ottawa M&M model. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014; 21(3):314–321 [PubMed: 24628757]

- 15.

- Cao V, Horn F, Laren T, Scott L, Giri P, Hidalgo D et al. 1080: patient-centered structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds in the medical ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2016; 44(12 Suppl 1):346 [PubMed: 29088002]

- 16.

- Carlos WG, Patel DG, Vannostrand KM, Gupta S, Cucci AR, Bosslet GT. Intensive care unit rounding checklist implementation. Effect of accountability measures on physician compliance. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015; 12(4):533–538 [PubMed: 25642750]

- 17.

- Ciccu-Moore R, Grant F, Niven BA, Paterson H, Stoddart K, Wallace A. Care and comfort rounds: improving standards. Nursing Management. 2014; 20(9):18–23 [PubMed: 24479923]

- 18.

- Cohn A. The ward round: what it is and what it can be. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2014; 75:(Suppl 6):C82–C85 [PubMed: 25040741]

- 19.

- Conroy KM, Elliott D, Burrell AR. Testing the implementation of an electronic process-of-care checklist for use during morning medical rounds in a tertiary intensive care unit: a prospective before-after study. Annals of Intensive Care. 2015; 5(1):60 [PMC free article: PMC4523566] [PubMed: 26239145]

- 20.

- Cook EJ, Randhawa G, Guppy A, Large S. A study of urgent and emergency referrals from NHS Direct within England. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(5):e007533 [PMC free article: PMC4431129] [PubMed: 25968002]

- 21.

- Cornell P, Gervis MT, Yates L, Vardaman JM. Impact of SBAR on nurse shift reports and staff rounding. Medsurg Nursing. 2014; 23(5):334–342 [PubMed: 26292447]

- 22.

- Cornell P, Townsend-Gervis M, Vardaman JM, Yates L. Improving situation awareness and patient outcomes through interdisciplinary rounding and structured communication. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2014; 44(3):164–169 [PubMed: 24531289]

- 23.

- Damiani LP, Cavalcanti AB, Moreira FR, Machado F, Bozza FA, Salluh JIF et al. A cluster-randomised trial of a multifaceted quality improvement intervention in Brazilian intensive care units (Checklist-ICU trial): statistical analysis plan. Critical Care and Resuscitation. 2015; 17(2):113–121 [PubMed: 26017129]

- 24.

- Dhillon P, Murphy RKJ, Ali H, Burukan Z, Corrigan MA, Sheikh A et al. Development of an adhesive surgical ward round checklist: a technique to improve patient safety. Irish Medical Journal. 2011; 104(10):303–305 [PubMed: 22256442]

- 25.

- Dixon-Woods M, Leslie M, Tarrant C, Bion J. Explaining Matching Michigan: an ethnographic study of a patient safety program. Implementation Science. 2013; 8:70 [PMC free article: PMC3704826] [PubMed: 23786847]

- 26.

- Dodek PM, Raboud J. Explicit approach to rounds in an ICU improves communication and satisfaction of providers. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003; 29(9):1584–1588 [PubMed: 12898001]

- 27.

- Dubose J, Teixeira PGR, Inaba K, Lam L, Talving P, Putty B et al. Measurable outcomes of quality improvement using a daily quality rounds checklist: one-year analysis in a trauma intensive care unit with sustained ventilator-associated pneumonia reduction. Journal of Trauma. 2010; 69(4):855–860 [PubMed: 20032792]

- 28.

- DuBose JJ, Inaba K, Shiflett A, Trankiem C, Teixeira PGR, Salim A et al. Measurable outcomes of quality improvement in the trauma intensive care unit: the impact of a daily quality rounding checklist. Journal of Trauma. 2008; 64(1):22–29 [PubMed: 18188094]

- 29.

- Gausvik C, Lautar A, Miller L, Pallerla H, Schlaudecker J. Structured nursing communication on interdisciplinary acute care teams improves perceptions of safety, efficiency, understanding of care plan and teamwork as well as job satisfaction. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2015; 8:33–37 [PMC free article: PMC4298312] [PubMed: 25609978]

- 30.

- Ham PB, Anderton T, Gallaher R, Hyrman M, Simmerman E, Ramanathan A et al. Development of electronic medical record-based “rounds report” results in improved resident efficiency, more time for direct patient care and education, and less resident duty hour violations. American Surgeon. 2016; 82(9):853–859 [PubMed: 27670576]

- 31.

- Hasibeder WR. Does standardization of critical care work? Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2010; 16(5):493–498 [PubMed: 20613503]

- 32.

- Have ECMT, Nap RE. Mutual agreement between providers in intensive care medicine on patient care after interdisciplinary rounds. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2014; 29(5):292–297 [PubMed: 23753243]

- 33.

- Henneman EA, Kleppel R, Hinchey KT. Development of a checklist for documenting team and collaborative behaviors during multidisciplinary bedside rounds. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2013; 43(5):280–285 [PubMed: 23615370]

- 34.

- Herring R, Caldwell G, Jackson S. Implementation of a considerative checklist to improve productivity and team working on medical ward rounds. Clinical Governance. 2011; 16(2):129–136

- 35.

- Herring R, Desai T, Caldwell G. Quality and safety at the point of care: how long should a ward round take? Clinical Medicine. 2011; 11(1):20–22 [PMC free article: PMC5873793] [PubMed: 21404777]

- 36.

- Hewson KM, Burrell AR. A pilot study to test the use of a checklist in a tertiary intensive care unit as a method of ensuring quality processes of care. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2006; 34(3):322–328 [PubMed: 16802484]

- 37.

- Hoke N, Falk S. Interdisciplinary rounds in the postanesthesia care unit. A new perioperative paradigm. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2012; 30(3):427–431 [PubMed: 22989586]

- 38.

- Holton R, Patel R, Eggebrecht M, Von Hoff B, Garrison O, McHale S et al. Rounding on rounds: creating a checklist for patient- and family-centered rounds. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2015; 30(5):493 [PubMed: 26180126]

- 39.

- Huynh E, Basic D, Gonzales R, Shanley C. Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds do not reduce length of hospital stay and 28-day re-admission rate among older people hospitalised with acute illness: an Australian study. Australian Health Review. 2016; [PubMed: 27883874]

- 40.

- Jacobowski NL, Girard TD, Mulder JA, Ely EW. Communication in critical care: family rounds in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2010; 19(5):421–430 [PMC free article: PMC3707491] [PubMed: 20810417]

- 41.

- Jitapunkul S, Nuchprayoon C, Aksaranugraha S, Chaiwanichsiri D, Leenawat B, Kotepong W et al. A controlled clinical trial of multidisciplinary team approach in the general medical wards of Chulalongkorn Hospital. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 1995; 78(11):618–623 [PubMed: 8576674]

- 42.

- Karalapillai D, Baldwin I, Dunnachie G, Knott C, Eastwood G, Rogan J et al. Improving communication of the daily care plan in a teaching hospital intensive care unit. Critical Care and Resuscitation. 2013; 15(2):97–102 [PubMed: 23931040]

- 43.

- Krepper R, Vallejo B, Smith C, Lindy C, Fullmer C, Messimer S et al. Evaluation of a standardized hourly rounding process (SHaRP). Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2014; 36(2):62–69 [PubMed: 23237186]

- 44.

- Lehnbom EC, Adams K, Day RO, Westbrook JI, Baysari MT. iPad use during ward rounds: an observational study. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2014; 204:67–73 [PubMed: 25087529]

- 45.

- Lepee C, Klaber RE, Benn J, Fletcher PJ, Cortoos PJ, Jacklin A et al. The use of a consultant-led ward round checklist to improve paediatric prescribing: an interrupted time series study. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2012; 171(8):1239–1245 [PubMed: 22628136]

- 46.

- Levett T, Caldwell G. Leadership training for registrars on ward rounds. Clinical Teacher. 2014; 11(5):350–354 [PubMed: 25041667]

- 47.

- Mansell A, Uttley J, Player P, Nolan O, Jackson S. Is the post-take ward round standardised? Clinical Teacher. 2012; 9(5):334–337 [PubMed: 22994475]

- 48.

- Mant T, Dunning T, Hutchinson A. The clinical effectiveness of hourly rounding on fall-related incidents involving adult patients in an acute care setting: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2012; 10:S63–S74 [PubMed: 27820281]

- 49.

- Mathias JM. Rounding tool off to a good start in improving patient satisfaction. OR Manager. 2014; 30(3):1–9 [PubMed: 24712236]

- 50.

- Meade CM, Bursell AL, Ketelsen L. Effects of nursing rounds: on patients’ call light use, satisfaction, and safety. American Journal of Nursing. 2006; 106(9):58–1 [PubMed: 16954767]

- 51.

- Meade CM, Kennedy J, Kaplan J. The effects of emergency department staff rounding on patient safety and satisfaction. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010; 38(5):666–674 [PubMed: 18842381]

- 52.

- Mercedes A, Fairman P, Hogan L, Thomas R, Slyer JT. The effectiveness of structured multidisciplinary rounding in acute care units on length of hospital stay and satisfaction of patients and staff: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2015; 13(8):41–53 [PubMed: 26455934]

- 53.

- Mitchell MD, Lavenberg JG, Trotta RL, Umscheid CA. Hourly rounding to improve nursing responsiveness: a systematic review. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2014; 44(9):462–472 [PMC free article: PMC4547690] [PubMed: 25148400]

- 54.

- Mohan N, Caldwell G. A considerative checklist to ensure safe daily patient review. Clinical Teacher. 2013; 10(4):209–213 [PubMed: 23834564]

- 55.

- Monaghan J, Channell K, McDowell D, Sharma AK. Improving patient and carer communication, multidisciplinary team working and goal-setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005; 19(2):194–199 [PubMed: 15759535]

- 56.

- Mosher HJ, Lose DT, Leslie R, Pennathur P, Kaboli PJ. Aligning complex processes and electronic health record templates: a quality improvement intervention on inpatient interdisciplinary rounds. BMC Health Services Research. 2015; 15:265 [PMC free article: PMC4499441] [PubMed: 26164546]

- 57.

- Narasimhan M, Eisen LA, Mahoney CD, Acerra FL, Rosen MJ. Improving nurse-physician communication and satisfaction in the intensive care unit with a daily goals worksheet. American Journal of Critical Care. 2006; 15(2):217–222 [PubMed: 16501141]

- 58.

- Newnham A, Hine C, Agwu JC. Impact of standardised documentation on post take ward round. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012; 97:(Suppl 1):A108–A109

- 59.

- Newnham AL, Hine C, Rogers C, Agwu JC. Improving the quality of documentation of paediatric post-take ward rounds: the impact of an acrostic. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2015; 91(1071):22–25 [PubMed: 25476019]

- 60.

- Norgaard K, Ringsted C, Dolmans D. Validation of a checklist to assess ward round performance in internal medicine. Medical Education. 2004; 38(7):700–707 [PubMed: 15200394]

- 61.

- O’Hare JA. Anatomy of the ward round. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008; 19(5):309–313 [PubMed: 18549930]

- 62.

- O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB, Haviley C, Slade ME, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a medical teaching unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010; 25(8):826–832 [PMC free article: PMC2896605] [PubMed: 20386996]

- 63.

- O’Leary KJ, Boudreau YN, Creden AJ, Slade ME, Williams MV. Assessment of teamwork during structured interdisciplinary rounds on medical units. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2012; 7(9):679–683 [PubMed: 22961774]

- 64.

- O’Leary KJ, Buck R, Fligiel HM, Haviley C, Slade ME, Landler MP et al. Structured interdisciplinary rounds in a medical teaching unit: improving patient safety. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011; 171(7):678–684 [PubMed: 21482844]

- 65.

- O’Leary KJ, Creden AJ, Slade ME, Landler MP, Kulkarni N, Lee J et al. Implementation of unit-based interventions to improve teamwork and patient safety on a medical service. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2015; 30(5):409–416 [PubMed: 24919598]

- 66.

- O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. Journal of Hospital Medicine.: Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company. 2011; 6(2):88–93 [PubMed: 20629015]

- 67.

- Pitcher M, Lin JTW, Thompson G, Tayaran A, Chan S. Implementation and evaluation of a checklist to improve patient care on surgical ward rounds. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2016; 86(5):356–360 [PubMed: 25962703]

- 68.

- Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Qurashi M, Singh P, Darzi A. Randomized clinical trial of the impact of surgical ward-care checklists on postoperative care in a simulated environment. British Journal of Surgery. 2014; 101(13):1666–1673 [PubMed: 25350855]

- 69.

- Reimer N, Herbener L. Round and round we go: rounding strategies to impact exemplary professional practice. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014; 18(6):654–660 [PubMed: 25305021]

- 70.

- Richmond C, Merrick E, Green T, Dinh M, Iedema R. Bedside review of patient care in an emergency department: the Cow Round. EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2011; 23(5):600–605 [PubMed: 21995475]

- 71.

- Savel RH, Goldstein EB, Gropper MA. Critical care checklists, the Keystone Project, and the Office for Human Research Protections: a case for streamlining the approval process in quality-improvement research. Critical Care Medicine. 2009; 37(2):725–728 [PubMed: 19114910]

- 72.

- Sharma S, Peters MJ, PICU/NICU Risk Action Group. ‘Safety by DEFAULT’: introduction and impact of a paediatric ward round checklist. Critical Care. 2013; 17(5):R232 [PMC free article: PMC4028750] [PubMed: 24479381]

- 73.

- Shaughnessy L, Jackson J. Introduction of a new ward round approach in a cardiothoracic critical care unit. Nursing in Critical Care. 2015; 20(4):210–218 [PubMed: 25598478]

- 74.

- Shoeb M, Khanna R, Fang M, Sharpe B, Finn K, Ranji S et al. Internal medicine rounding practices and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2014; 9(4):239–243 [PubMed: 24493566]

- 75.

- Simpson SQ, Peterson DA, O’Brien-Ladner AR. Development and implementation of an ICU quality improvement checklist. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2007; 18(2):183–189 [PubMed: 17473547]

- 76.

- Sobaski T, Abraham M, Fillmore R, McFall DE, Davidhizar R. The effect of routine rounding by nursing staff on patient satisfaction on a cardiac telemetry unit. Health Care Manager. 2008; 27(4):332–337 [PubMed: 19011416]

- 77.

- Teixeira PGR, Inaba K, Dubose J, Melo N, Bass M, Belzberg H et al. Measurable outcomes of quality improvement using a daily quality rounds checklist: two-year prospective analysis of sustainability in a surgical intensive care unit. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2013; 75(4):717–721 [PubMed: 24064888]

- 78.

- Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Neilands TB, Frankel A, Helmreich RL. The effect of executive walk rounds on nurse safety climate attitudes: a randomized trial of clinical units. BMC Health Services Research. 2005; 5:28 [PMC free article: PMC1097728] [PubMed: 15823204]

- 79.

- Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Neilands TB, Frankel A, Helmreich RL. Correction: The effect of executive walk rounds on nurse safety climate attitudes: a randomized trial of clinical units [ISRCTN85147255]. BMC Health Services Research. 2005; 5:46 [PMC free article: PMC1177946] [PubMed: 15949037]

- 80.

- Thompson AG, Jacob K, Fulton J, McGavin CR. Do post-take ward round proformas improve communication and influence quality of patient care? Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2004; 80(949):675–676 [PMC free article: PMC1743139] [PubMed: 15537856]

- 81.

- Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2005; 200(4):538–545 [PubMed: 15804467]

- 82.

- Van Eaton EG, McDonough K, Lober WB, Johnson EA, Pellegrini CA, Horvath KD. Safety of using a computerized rounding and sign-out system to reduce resident duty hours. Academic Medicine. 2010; 85(7):1189–1195 [PubMed: 20592514]

- 83.

- Weiss CH, Dibardino D, Rho J, Sung N, Collander B, Wunderink RG. A clinical trial comparing physician prompting with an unprompted automated electronic checklist to reduce empirical antibiotic utilization. Critical Care Medicine. 2013; 41(11):2563–2569 [PMC free article: PMC3812385] [PubMed: 23939354]

- 84.

- Weiss CH, Moazed F, McEvoy CA, Singer BD, Szleifer I, Amaral LAN et al. Prompting physicians to address a daily checklist and process of care and clinical outcomes: a single-site study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011; 184(6):680–686 [PMC free article: PMC3208596] [PubMed: 21616996]

- 85.

- Weiss CH, Persell SD, Wunderink RG, Baker DW. Empiric antibiotic, mechanical ventilation, and central venous catheter duration as potential factors mediating the effect of a checklist prompting intervention on mortality: an exploratory analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 2012; 12:198 [PMC free article: PMC3409043] [PubMed: 22794349]

- 86.

- Wild D, Nawaz H, Chan W, Katz DL. Effects of interdisciplinary rounds on length of stay in a telemetry unit. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2004; 10(1):63–69 [PubMed: 15018343]

- 87.

- Wilson FEJ, Newman A, Ilari S. Innovative solutions: optimal patient outcomes as a result of multidisciplinary rounds. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2009; 28(4):171–173 [PubMed: 19546724]

- 88.

- Wright DN. Does a post-take ward round proforma have a positive effect on completeness of documentation and efficiency of information management? Health Informatics Journal. 2009; 15(2):86–94 [PubMed: 19474222]

- 89.

- Wright S, Bowkett J, Bray K. The communication gap in the ICU-a possible solution. Nursing in Critical Care. 1996; 1(5):241–244 [PubMed: 9594125]

- 90.

- Young MP, Gooder VJ, Oltermann MH, Bohman CB, French TK, James BC. The impact of a multidisciplinary approach on caring for ventilator-dependent patients. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 1998; 10(1):15–26 [PubMed: 10030783]

- 91.

- Zhang R. Investigating the prevention of hospital-acquired infection through standardized teaching ward rounds in clinical nursing. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2015; 14(2):3753–3759 [PubMed: 25966144]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 8Review protocol: Structured ward rounds

| Review question: Do structured ward rounds improve processes and patient outcomes? | |

|---|---|

| Rationale | Often the way the ward rounds are performed is not efficient - ward rounds are often done in a geographical order rather than on the basis of patient priority. Each patient does not always get all the components of the ward round because generally there is no structure and it depends on individual preference, personalities and recall. The components of the ward round (for example, examination, VTE risk assessment or review, medication review or explanation to the patient) are the same for each patient thus the process of the ward round could be structured. The provision of a ward round checklists and/or daily goal charts will ensure all components are delivered and therefore should ensure optimum care is provided. We are looking at systems rather than conditions so we will not be looking at condition-specific checklists. |

| Topic code | T6-6. |

| Population |

Adults and young people (16 years and over) admitted to hospital with a suspected or confirmed AME. No strata (checklists and charts). |

| Intervention | Structured ward round models including using:

|

| Comparison | No ward round checklists or daily goal charts. |

| Outcomes |

|

| Exclusion | Operating theatres (surgical literature can be referenced in other considerations if necessary). |

| Search criteria |

The databases to be searched are: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library. Date limits for search: 1990. Language: English. |

| The review strategy | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Analysis |

Data synthesis of RCT data. Meta-analysis where appropriate will be conducted. Studies in the following subgroup populations will be included in subgroup analysis:

|

| Exclusions | Countries: Non- OECD. |

| Key papers | None identified. |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

C.1. Checklist versus no checklist

C.2. Prompted versus unprompted

C.3. Explicit rounding approach versus standard rounding approach

C.4. Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds versus standard physician-centred rounds

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (729K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 9Clinical evidence profile: Checklist versus no checklist

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Checklist versus no checklist | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Adherence to care - unadjusted (Missed or delayed investigations) - Diagnosis (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None |

69/70 (98.6%) | 40% | RR 2.46 (1.94 to 3.14) | 584 more per 1000 (from 376 more to 856 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Adherence to care - unadjusted (Missed or delayed investigations) - Investigations (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None |

66/70 (94.3%) | 57% | RR 1.65 (1.38 to 1.98) | 370 more per 1000 (from 217 more to 559 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Adherence to care - unadjusted (Missed or delayed investigations) - Further tests (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | serious3 | None |

55/70 (78.6%) | 52% | RR 1.51 (1.21 to 1.89) | 265 more per 1000 (from 109 more to 463 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Adherence to care - unadjusted (missed or delayed treatments) - Management plan (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | serious3 | None |

70/70 (100%) | 81% | RR 1.23 (1.12 to 1.36) | 186 more per 1000 (from 97 more to 292 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Adherence to care - unadjusted (missed or delayed treatments) - DVT prophylaxis (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None |

37/70 (52.9%) | 6% | RR 8.81 (3.93 to 19.74) | 469 more per 1000 (from 176 more to 1000 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Mortality (follow-up 3 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious3 | None |

7/653 (1.1%) | 5.3% | RR 1.13 (0.38 to 3.34) | 7 more per 1000 (from 30 fewer to 124 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Overall adherence to care - adjusted (missed or delayed treatments) (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | None | - | 0% | OR 6.38 (5.06 to 8.05) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgrade by 1 increment if the majority of evidence had indirect outcomes.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Table 10Clinical evidence profile: Daily rounding checklist-prompted versus daily rounding checklist- unprompted

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Prompted versus unprompted | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (adjusted OR) - ICU mortality (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | - | 0% | OR 0.36 (0.13 to 1) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (adjusted OR) - Hospital mortality (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None | - | 0% | OR 0.34 (0.15 to 0.77) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| ICU length of stay - ICU length of stay (follow-up not stated) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 140 | 125 | - | MD 1.4 lower (2.82 lower to 0.02 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Hospital mortality (follow-up 6 months) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None |

30/171 (17.5%) | 24% | RR 0.73 (0.47 to 1.15) | 65 fewer per 1000 (from 127 fewer to 36 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

Downgraded by 1 increment if the majority of the evidence was at high risk of bias, and downgraded by 2 increments if the majority of the evidence was at very high risk of bias. All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Table 11Clinical evidence profile: Explicit rounding approach versus standard rounding approach

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Explicit rounding versus standard rounding | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Patient satisfaction (overall satisfaction) (follow-up unclear) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious2 | None |

341/472 (72.2%) | 48.6% | RR 1.49 (1.05 to 2.1) | 238 more per 1000 (from 24 more to 535 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Staff satisfaction (follow-up 12 days before and 19 days after) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None |

1467/1544 (95%) |

790/915 (86.3%) | RR 1.1 (1.07 to 1.03) | 86 more per 1000 (from 26 more to 60 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Table 12Clinical evidence profile: Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds versus standard physician-centred rounds

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Structured interdisciplinary bedside versus standard physician-centred rounds | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Job satisfaction (follow-up not stated; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 24 | 38 | - | MD 0.76 higher (0.49 to 1.03 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Table 13Clinical evidence profile: Structured interdisciplinary rounds (SIDR) versus control (unknown)

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Structured interdisciplinary rounds (SIDR) versus control (unknown) | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Teamwork climate score (staff satisfaction) - unadjusted (follow-up 6 months and 2 years; range of scores: 0-100; Better indicated by higher values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 303 | 231 | - | MD 3.15 higher (0.84 to 5.45 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Adverse events (adjusted rate ratio) - Any adverse events (follow-up 5.5 months and 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | observational studies | very serious1 | serious2 | no serious indirectness | very serious3 | None | - | 0% | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.53) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Adverse events (adjusted rate ratio) - Preventable adverse events (follow-up 5.5 months and 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | observational studies | very serious1 | serious2 | no serious indirectness | very serious3 | None | - | 0% | 0.55 (0.15 to 2.01) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Adverse events (adjusted rate ratio) - Serious adverse events (follow-up 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | very serious3 | None | - | 0% | 0.86 (0.39 to 1.9) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| ICU length of stay (follow-up 1991 - 1995; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 469 | 469 | - | MD 4.2 lower (5.8 to 2.6 lower) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Hospital length of stay (follow-up 1991 – 1995, 6 months and 24 weeks; Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | 1966 | 2253 | - | SMD 0.03 lower (0.09 lower to 0.03 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Length of stay (RCT) (follow-up (baseline); Better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | serious3 imprecision | None | 42 | 42 | - | MD 0.34 higher (0.43 lower to 1.11 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

Downgraded by 1 or 2 increments because the heterogeneity is I2=87%, unexplained by subgroup analysis.

- 3

Downgraded by 1 increment if the confidence interval crossed 1 MID or by 2 increments if the confidence interval crossed both MIDs.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 14Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Al-mahrouqi 20132 | Inappropriate study design- audit of post-acute consultant ward round before and after introduction of a proforma |

| Alamri 20163 | Inappropriate study design- clinical review of surgical ward round checklist |

| Aung 20165 | Inappropriate study design- quality improvement project to improve prescribing in the elderly. |

| Anonymous 2008B1 | Commentary; no data |

| Baba 20116 | No outcome data |

| Bhamidipati 20167 | Systematic review. Two references ordered |

| Blucher 20148 |

Evaluation of ward safety checklist for the morning post-take ward round Incorrect study population (acute surgical unit) |

| Boland 2015A9 | Inappropriate study design- audit to measure the impact of a ward round checklist. |

| Butcher 201312 | Intervention does not meet inclusion criteria, there is not a distinct difference between the intervention and comparator |

| Calder 201414 |

Survey conducted before and after the development, implementation, and evaluation of a rounds model No relevant outcomes |

| Carlos 201516 |

Study on physician compliance with checklist use No comparison and no relevant outcomes |

| CAO 201615 | Abstract only |

| Ciccu-Moore 201417 |

Description of a checklist No outcome data in analysable format |

| Cohn 201418 | Narrative review |

| Cook 2015A20 | Not related to structured ward round. A study about urgent and emergency referrals from NHS direct within England |

| Cornell 201421 |

Before-and-after study of implementation of situation-background-assessment-recommendation protocol No relevant outcomes |

| Cornell 2014A22 |

Study on interdisciplinary rounding and structured communication (no physicians involved) No relevant outcomes and no relevant comparison |

| Damiani 201523 | RCT but from a non-OECD country (Brazil) |

| Dhillon 201124 |

Incorrect study population (surgical ward) No relevant outcomes |

| DuBose 200828 |

Evaluation of a daily quality rounding checklist Incorrect study population (trauma intensive care unit) |

| DuBose 201027 | Incorrect study population (trauma intensive care unit) |

| Ham 201630 | Incorrect intervention- effect of ‘rounds report’ on surgery residents |

| Hasibeder 201031 | Narrative review |

| Hale 201538 | Inappropriate study design- quality improvement project involving the introduction of a ward round check list for daily use. |

| Have 201432 |

Study on interdisciplinary rounds No relevant outcomes |

| Henneman 201333 |

Description of development and reliability testing of checklist No intervention and no data |

| Herring 201135 |

Description of ward round checklist No data |

| Herring 2011B34 |

Qualitative evaluation of development and testing of checklist for ward rounds No quantitative data |

| Hewson 200636 |

Pilot study to evaluate the use of a checklist No comparison and no relevant outcomes |

| Hoke 201237 |

Description of a perioperative paradigm used in interdisciplinary rounds Incorrect study population (post-anaesthesia care unit) |

| Holton 201538 |

Brief summary of initial findings of a survey No relevant data |

| Huynh 201639 | No extractable outcomes |

| Jacobowski 201040 |

Before and after study of introducing structured interdisciplinary family ward rounds versus structured interdisciplinary normal ward rounds Incorrect comparison (ward round was the same apart from attendance of the family who was able to ask questions and received a summary by the physician in lay language) |

| Jitapunkul 199541 | Incorrect intervention. Study aimed to evaluate the effect of a MDT approach. Study considered for inclusion in the MDT review. |

| Karalapillai 201342 |

Development and pro-forma of a daily care plan; targeted at nurses only No relevant outcomes/data |

| Krepper 201443 | Incorrect study population (vascular surgical unit) |

| Lehnbom 201444 |

Slides of a PowerPoint presentation No relevant outcome data |

| Lepee 201245 | Incorrect study population (paediatric ward) |

| Levett 201446 |

Survey of views post-induction of a structured checklist No comparison |

| Mansell 201247 |

Summary of an audit after introduction of a ward round checklist No comparison and no data |

| Mant 201248 | Systematic review; protocol only |

| Mathias 201449 |

No comparison No outcome data |

| Meade 200650 | Unable to extract outcome data as patient numbers are not provided |

| Meade 201051 | No relevant intervention, comparison and analysis (Three types of ward rounds introduced on ED but treated as one intervention in the analyses and compared to before introduction of any ward round. Also, no variation data presented so would have been narrative results only.) |

| Mercedes 201552 | Highly relevant planned systematic review but at protocol stage only |

| Mitchell 201453 | Systematic review (references checked) |

| Mohan 201354 |

Description of a checklist No data |

| Monaghan 200555 | Not relevant comparison (study compares ward rounds with different types of structured forms but no comparator of unstructured ward rounds) |

| Mosher 201556 |

Quality improvement intervention of interdisciplinary rounds No relevant data in analysable format |

| Newnham 201559 |

Evaluation of a mnemonic, created to reflect the aspects of care that should be documented after every ward round, on the completeness of note keeping Incorrect study population (paediatric ward) |

| Newnham 201258 |

Evaluation of standardised documentation on post take ward rounds Incorrect study population (paediatric ward) |

| Norgaard 2004A60 |

Description of development and validation (content and construct) of checklist No comparison and no relevant outcomes |

| O’Hare 200861 | Narrative review of ward rounds |

| O’Leary 2012A63 | No relevant outcomes to extract |

| Pitcher 201667 |

Incorrect intervention- structured checklist in a surgical ward round. Incorrect study design- quality assurance project |

| Pucher 2014A68 | RCT but incorrect environment and patient population (simulation on post-surgical ward) |

| Reimer 201469 | Narrative review of rounding strategies |

| Richmond 201170 |

Observational study of a centralised whiteboard handover followed by a multidisciplinary review of each patient No relevant intervention |

| Savel 200971 | Literature review |

| Sharma 201372 |

Observational study investigating impact of checklist on ward rounds Incorrect study population (paediatric ICU) |

| Shaughnessy 201573 |

Qualitative study after induction of a new ward round approach No quantitative data |

| Shoeb 201474 |

No relevant outcomes No extractable data |

| Simpson 200775 |

Description of development and implementation of a checklist No data |

| Sobaski 200876 | No extractable data |

| Teixeira 201377 |

Quality improvement using a daily quality rounds checklist Incorrect study population (surgical intensive care unit) |

| Thomas 2005A79 |

Correction for the Thomas 2005D paper No data |

| Thomas 2005D78 | No relevant outcomes |

| Thompson 200480 |

Brief summary of post-take ward round proforma implementation No relevant outcomes (only changes in rates of documentation) |

| Van Eaton 201082 |

Evaluation of a computerised rounding and sign-out system Not relevant study population (more than 50% surgical patients, trauma and paediatrics) |

| Van Eaton 200581 |

RCT evaluating a computerised rounding and sign-out system No relevant outcomes |

| Weiss 201285 | No extractable data |

| Wilson 200987 | No extractable data |

| Wild 200486 | Incorrect intervention. Study evaluated the effect of interdisciplinary ward rounds. Study considered for inclusion in the MDT review |

| Wright 199689 |

No outcome data No relevant comparison |

| Zhang 201591 | No relevant outcomes |

Appendix H. Excluded health economic studies

No health economic studies were excluded from this review.

Footnotes

- (a)

NICE’s guideline on medicines optimisation includes recommendations on medicines-related communication systems when patients move from one care setting to another, medicines reconciliation, clinical decision support, and medicines-related models of organisational and cross-sector working.

- Structured ward rounds - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service d...Structured ward rounds - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...