NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details16. Emergency department opening hours

16.1. Introduction

Emergency Departments are usually open 24 hours a day, but in recent years there is an increasing trend to close some at nights. Often in quieter, more rural units this is because there is very little demand at night; but it may also happen as part of service consolidation to assure patient safety.

The effect of limiting ED opening times may be minimal. It maybe that the demand is swept up elsewhere (for example, in other hospitals or by other healthcare providers, for example, GPs or other community carers); however, this maybe at the expense of longer journey times and possible worsening of the patient’s condition. There could be further knock on effects to the ambulance service with vehicles being used for longer journeys not being able to respond to other emergency calls. However, the cost of keeping a 24 hour unit in all acute hospitals may be hugely expensive.

Therefore, closing ED’s at night should only be considered if clinically safe and cost effective to the whole healthcare economy. The guideline committee wanted to know if any work had been done in this area to assure this, and in what circumstances this had been shown.

16.2. Review question: Is 24-hour open access to ED more clinically and cost effective compared with limited opening times to ED?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

16.3. Clinical evidence

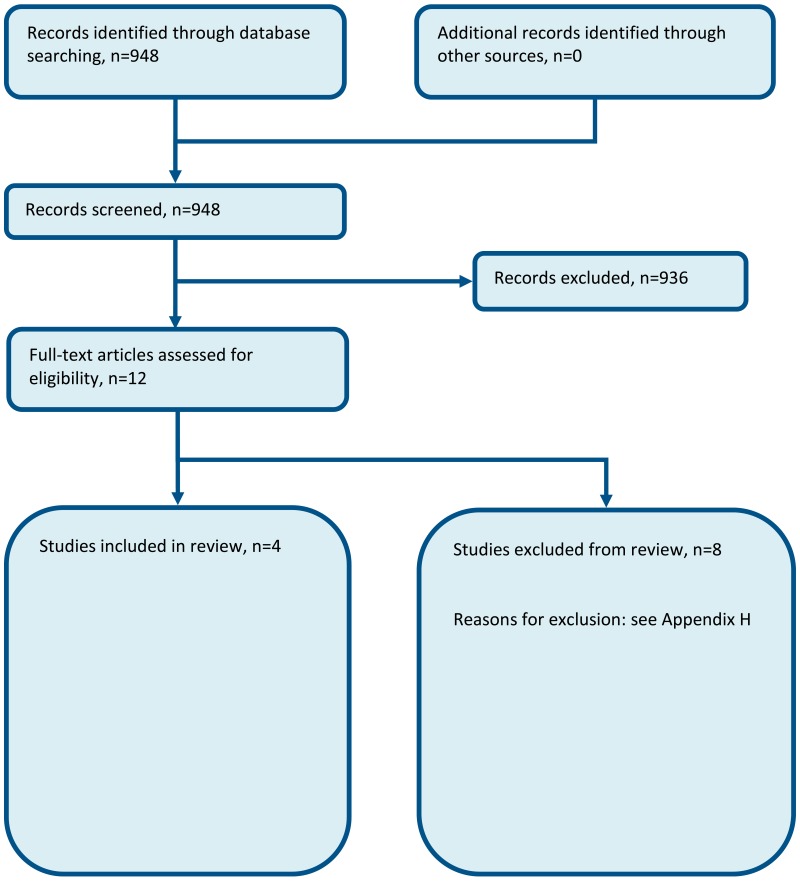

Four studies were included in the review; 1 controlled before-after study and 3 cohort studies,7–9,11 these are summarised in Table 2 below. Evidence from these studies is summarised in the clinical evidence summaries below (Table 3 – Table 7). See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, forest plots in Appendix C, study evidence tables in Appendix D, GRADE tables in Appendix F and excluded studies list in Appendix G.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Clinical evidence summary: Day-time only ED versus 24 hour ED access.

Table 7

Clinical evidence summary: Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED.

Table 4

Clinical evidence summary: ED closure versus 24 hour ED access.

Table 5

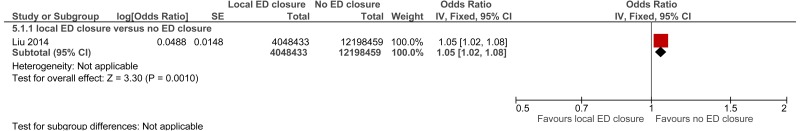

Clinical evidence summary: local ED closure versus no ED closure.

Table 6

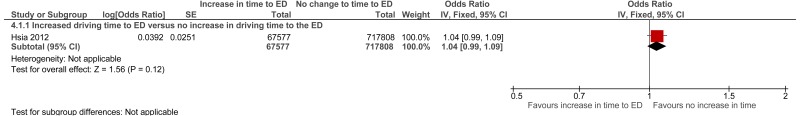

Clinical evidence summary: Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED.

16.4. Economic evidence

Published literature

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

In the absence of economic evidence, unit costs were presented to the committee – see Chapter 41 Appendix I.

16.5. Evidence statements

Clinical

Restricted and closure of ED versus 24 hour ED access

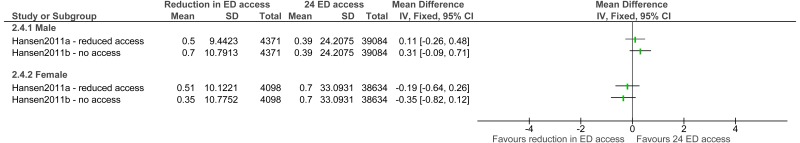

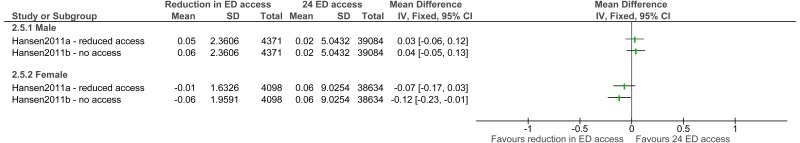

One study conducted in Denmark reported gender stratified healthcare utilisation rates on in-person GP consultations, telephone GP consultations, home visits by GPs, ED visits and hospital admission. The evidence suggested that there was no difference in outcomes when ED hours were restricted (very low quality). When the ED was closed, the evidence suggested a reduction in GP telephone consultations, in-person consultation rates and home consultation rates amongst female patients, but not males. The evidence suggested there was no effect on ED visit rate or admission rat (very low quality).

Local ED closure versus no ED closure

One study set in the USA suggested a possible increase in mortality with ED closure compared to no ED closure (very low quality).

Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

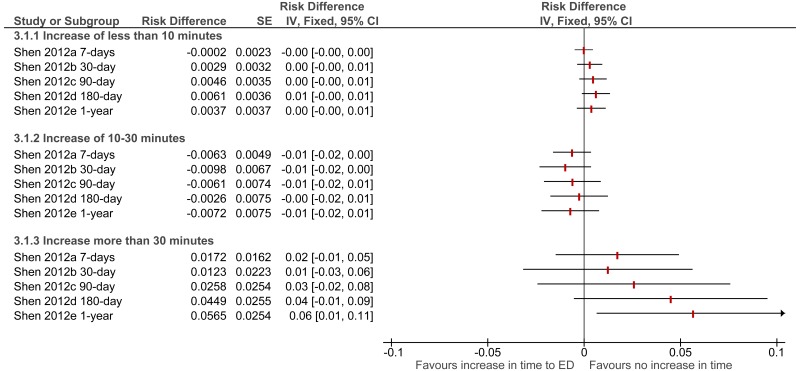

One study set in the USA suggested a possible increase in mortality amongst patients with time-sensitive conditions when driving time to nearest ED was increased (very low quality). One study set in the USA suggested a possible increase in mortality amongst patients with time sensitive conditions when driving time to the nearest ED was increased more than 30 minutes (very low quality).

Economic

No relevant economic evaluations were identified.

16.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations | - |

| Research recommendation | RR8. What is the clinical and cost effectiveness of limiting emergency department opening hours, and what effect does this have on local healthcare provision and outcomes for people with medical emergencies? |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Mortality, quality of life, avoidable adverse events, impact on other services and patient and/or carer satisfaction were considered by the committee to be critical outcomes. Ambulance transfer times and number of ED presentations were considered important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

A total of 4 observational studies were identified. The evidence for restriction of ED opening hours was mixed. One study set in USA suggested a possible increase in mortality with ED closure compared to no ED closure. One study set in the USA suggested a possible increase in mortality amongst patients with time-sensitive conditions when driving time to nearest ED was increased (very low quality). Another study set in the USA suggested a possible increase in mortality amongst patients with time sensitive conditions when driving time to the nearest ED was increased more than 30 minutes (very low quality). Evidence from 1 study conducted in Denmark reported gender-stratified healthcare utilisation rates of in-person GP consultations, telephone GP consultations, home visits by GPs, ED visits and hospital admissions. Data were collected only from the sample population, and therefore the evidence did not take into account any overall impact on the services. The evidence suggested that there was no difference in outcomes when ED hours were restricted. However, after the ED was closed the evidence suggested a reduction in GP telephone consultations, in-person consultation rates and home consultation rates amongst female patients. The evidence suggested there was no effect on ED attendances or admission rates. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient and/or carer satisfaction, and ambulance transfer times. A positive or permissive recommendation to limit ED opening hours would require evidence showing that patient outcomes would not worsen and that health care utilisation would be reduced. The direction and quality of evidence currently identified would not permit such a recommendation, particularly as it was not directly applicable to the UK health system. The committee noted that a research protocol which fulfilled the requirements for the review question was currently being developed within the UK. Therefore, the committee considered a research recommendation would be the most appropriate until this evidence from this research was available. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

No economic studies were included. Unit costs of ED visits and alternative care services were provided to aid cost-effectiveness considerations (Chapter 14 Appendix I). Further economic analysis could not be undertaken due to the quality of the evidence. Although 1 included study reported healthcare utilisation from a patient perspective, the study did not explore the impact on other EDs that would need to absorb the additional patients. Therefore, the full economic and resource impact could not be considered based on the outcomes of this study. Reducing the hours of or closing an ED could be cost-saving if it reduces overall healthcare utilisation. This includes the impact on other EDs, alternative urgent care services and other emergency care resources such as ambulance services. This would only be cost-effective if it is clinically safe and those services that treat the redirected patients have the capacity to do so without a negative impact on their current service. The committee concluded that more research was needed to assess the cost impact and cost-effectiveness of limited ED opening hours. |

| Quality of evidence |

The evidence was graded at very low quality. All evidence was downgraded for study design, whilst all but one was further downgraded for risk of bias. Three of the 4 studies were downgraded for indirectness as the evidence was combined for ED restriction, ED closure and full hospital closure. There were no economic studies included in the review. |

| Other considerations |

The committee noted that there are very different reasons for ED closure and ED restriction. For example, in the UK, restriction in ED hours usually occurs when there is little demand for the service, such as overnight in smaller rural EDs. Closures typically occur in EDs when there is a consolidation of services in an area, such as in urban areas. However, overnight closures in EDs may also be due to workforce shortages. Closures would not normally occur where this would lead to an absence of ED provision in an area, as ED provision is an essential service. Often the closed EDs have been replaced by another facility such as an Urgent Care Centre. Currently, there is little research evidence to inform decision making about these closures. Distance to an ED is an important factor in acute medical emergencies and the committee discussed the importance of the first hour (the ‘golden hour’) when, in certain acute conditions, access to curative interventions is most likely to be effective (for example, stroke). The committee noted that an NIHR –funded trial is underway. This study is a large controlled interrupted time series study which aims to analyse both ED closure and restriction in ED hours. Furthermore, this study includes both healthcare utilisation outcomes and patient safety outcomes and would be directly applicable to the UK population. |

References

- 1.

- Impact of closing Emergency Departments in England (closED). Health Technology Assessment, 2015. Available from: http://www

.nets.nihr .ac.uk/__data/assets /pdf_file/0013/133033/PRO-13-10-42.pdf - 2.

- Congdon P. The development of gravity models for hospital patient flows under system change: a Bayesian modelling approach. Health Care Management Science. 2001; 4(4):289–304 [PubMed: 11718461]

- 3.

- Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2014. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent; 2014. Available from: http://www

.pssru.ac.uk /project-pages/unit-costs/2014/index .php - 4.

- Department of Health. NHS reference costs 2013-14. 2014. Available from: http://www

.gov.uk/government /publications /nhs-reference-costs-2013-to-2014 [Last accessed: 12 March 2015] - 5.

- El Sayed M, Mitchell PM, White LF, Rubin-Smith JE, Maciejko TM, Obendorfer DT et al. Impact of an emergency department closure on the local emergency medical services system. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012; 16(2):198–203 [PubMed: 22191683]

- 6.

- Fisher K, Bonalumi N. Lessons learned from the merger of two emergency departments. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2000; 30(12):577–579 [PubMed: 11132344]

- 7.

- Hansen KS, Enemark U, Foldspang A. Health services use associated with emergency department closure. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2011; 16(3):161–166 [PubMed: 21389061]

- 8.

- Hsia RY, Kanzaria HK, Srebotnjak T, Maselli J, McCulloch C, Auerbach AD. Is emergency department closure resulting in increased distance to the nearest emergency department associated with increased inpatient mortality? Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012; 60(6):707–715 [PMC free article: PMC4096136] [PubMed: 23026784]

- 9.

- Liu C, Srebotnjak T, Hsia RY. California emergency department closures are associated with increased inpatient mortality at nearby hospitals. Health Affairs. 2014; 33(8):1323–1329 [PMC free article: PMC4214135] [PubMed: 25092832]

- 10.

- Mitchell A, Krmpotic D. What happens when a hospital closes its emergency department: our experience. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2008; 34(2):126–129 [PubMed: 18358350]

- 11.

- Shen YC, Hsia RY. Does decreased access to emergency departments affect patient outcomes? Analysis of acute myocardial infarction population 1996-2005. Health Services Research. 2012; 47(1 Pt 1):188–210 [PMC free article: PMC3258371] [PubMed: 22091922]

- 12.

- Sun BC, Mohanty SA, Weiss R, Tadeo R, Hasbrouck M, Koenig W et al. Effects of hospital closures and hospital characteristics on emergency department ambulance diversion, Los Angeles County, 1998 to 2004. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006; 47(4):309–316 [PubMed: 16546614]

- 13.

- Teljeur C, Barry J, Kelly A. The potential impact on travel times of closure and redistribution of A&E units in Ireland. Irish Medical Journal. 2004; 97(6):173–175 [PubMed: 15305619]

Appendices

Appendix A. Review protocol

Table 8Review protocol: ED opening hours

| Review question | Is 24-hour open access to ED more clinically and cost effective compared with limited opening times to ED? |

|---|---|

| Guideline condition and its definition | Acute Medical Emergencies. Definition: people with suspected or confirmed acute medical emergencies or at risk of an acute medical emergency. |

| Review population | Adults and young people (16 years and over) with a suspected or confirmed AME. |

| Adults and young people (16 years and over). | |

| Line of therapy not an inclusion criterion. | |

|

Interventions and comparators: generic/class; specific/drug (All interventions will be compared with each other, unless otherwise stated) |

Access to ED; 24 hour access to ED. Access to ED; undefined ‘usual’ access to ED. Reduced access to ED; restricted access with pre-planned diversion to other services. Reduced access to ED; restricted access without pre-planned diversion. Reduced access to ED; ED closure (without hospital closure). |

| Outcomes |

|

| Study design | Systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs, RCTs, observational studies only to be included if no relevant SRs or RCTs are identified. |

| Unit of randomisation |

Patient. Hospital. |

| Crossover study | Not permitted. |

| Minimum duration of study | Not defined. |

| Other exclusions |

Major trauma centres. Walk in centres. Minor injury units. Urgent care centres co-located in EDs, unless an unselected population presenting with emergencies can access the service. Whole hospital closing. Non-OECD country. |

| Population stratification |

Unselected population. Severely ill patients. Non-severely ill patients. |

| Reasons for stratification | If a population is selected in the study in may be that severely ill patients (such as those with acute myocardial infarction) will be affected by a restriction in ED opening hours to a greater degree. Trauma patients are excluded from the scope so studies which purposely select them will be excluded. |

| Subgroup analyses if there is heterogeneity |

|

| Search criteria |

Databases: Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library. Date limits for search: 1990. Language: English. |

Appendix B. Clinical article selection

Appendix C. Forest plots

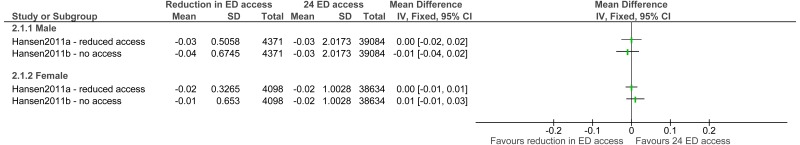

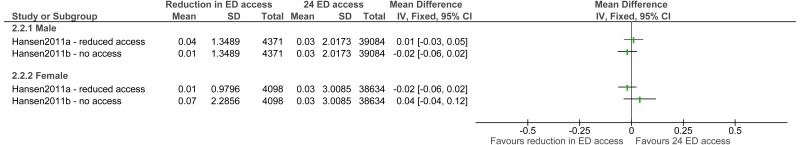

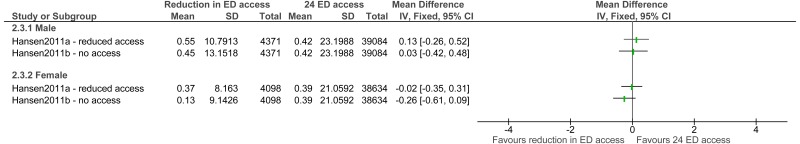

C.1. Gradual closure of ED versus 24 hour ED access

Figure 2ED visit rate

Note: adjusted for age, cohabitation, education level, family income, and the yearly trend to control for pre-existing trends in the use of health services.

Figure 3Admission rate

Note: adjusted for age, cohabitation, education level, family income, and the yearly trend to control for pre-existing trends in the use of health services.

Figure 4In-person GP consultation rate

Note: adjusted for age, cohabitation, education level, family income, and the yearly trend to control for pre-existing trends in the use of health services.

Figure 5Telephone GP consultation rate

Note: adjusted for age, cohabitation, education level, family income, and the yearly trend to control for pre-existing trends in the use of health services.

C.2. Local ED closure versus no ED closure

C.3. Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Download PDF (427K)

Appendix E. Economic evidence tables

No relevant health economic studies were identified.

Appendix F. GRADE tables

Table 9Clinical evidence profile: Day-time only ED versus 24 hour ED access

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Day-time only ED | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Male ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 13% | - | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 20 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 8% | - | 0 more per 1000 (from 10 fewer to 10 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 17% | - | 10 more per 1000 (from 30 fewer to 50 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 19% | - | 20 fewer per 1000 (from 60 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 284% | - | 130 more per 1000 (from 260 fewer to 520 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 353% | - | 20 fewer per 1000 (from 350 fewer to 310 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 197% | - | 310 more per 1000 (from 90 fewer to 710 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 330% | - | 190 fewer per 1000 (from 640 fewer to 260 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Non-randomised trials | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 15% | - | 30 more per 1000 (from 60 fewer to 120 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | None | - | 24% | - | 70 fewer per 1000 (from 170 fewer to 30 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Note: due to rounding data only accurate to the nearest 10 per 1000

Table 10Clinical evidence profile: ED closure versus 24 hour ED access

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | ED closure | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Male ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 13% | - | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 40 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 8% | - | 10 more per 1000 (from 10 fewer to 30 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 17% | - | 20 fewer per 1000 (from 60 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 19% | - | 40 fewer per 1000 (from 40 fewer to 120 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 284% | - | 30 more per 1000 (from 420 fewer to 480 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 385% | - | 260 fewer per 1000 (from 610 fewer to 90 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 197% | - | 310 more per 1000 (from 90 fewer to 710 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 330% | - | 350 fewer per 1000 (from 820 fewer to 120 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 15% | - | 40 more per 1000 (from 50 fewer to 130 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 24% | - | 120 fewer per 1000 (from 230 fewer to 10 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Note: due to rounding data only accurate to the nearest 10 per 1000

Table 11Clinical evidence profile: ED closure versus 24 hour ED access

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | ED closure | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Male ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 13% | - | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 40 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female ED visit rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 8% | - | 10 more per 1000 (from 10 fewer to 30 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 17% | - | 20 fewer per 1000 (from 60 fewer to 20 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female admission rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 19% | - | 40 more per 1000 (from 40 fewer to 120 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 284% | - | 30 more per 1000 (from 420 fewer to 480 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female in-person GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 385% | - | 260 fewer per 1000 (from 610 fewer to 90 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 197% | - | 310 more per 1000 (from 90 fewer to 710 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female telephone GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 330% | - | 350 fewer per 1000 (from 820 fewer to 120 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Male home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 15% | - | 40 more per 1000 (from 50 fewer to 130 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Female home GP consultation rate (follow-up 1 to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | very serious1 | no serious inconsistency | no serious indirectness | no serious imprecision | none | - | 24% | - | 120 fewer per 1000 (from 230 fewer to 10 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Note: due to rounding data only accurate to the nearest 10 per 1000.

Table 12Clinical evidence profile: local ED closure versus no ED closure

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Local ED closure versus no ED closure | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality - local ED closure versus no ED closure (follow-up in-hospital) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | no serious risk of bias2 | no serious inconsistency | serious1 | no serious imprecision | none | 4,048,433 | 12,198,459 | OR 1.05 (1.02 to 1.08) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

The majority of evidence did not differentiate between a reduction in ED opening hours, ED closures, or whole hospital closures.

- 2

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Table 13Clinical evidence profile: Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (follow-up in-hospital) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | no serious risk of bias2 | no serious inconsistency | serious1 | no serious imprecision | none | 67577 | 693,827 | OR 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | - |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

The majority of evidence did not differentiate between a reduction in ED opening hours, ED closures, or whole hospital closures.

- 2

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

Table 14Clinical evidence profile: Less than 10 minutes increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Increased driving time | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (follow-up 7 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 141,746 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.00 (-0.00-0.01) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 5 fewer to 4 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 30 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 141,746 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.00 (-0.00-0.01) | 3 more per 1000 (from 3 fewer to 9 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 90 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 141,746 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.00 (-0.00-0.01) | 5 more per 1000 (2 fewer to 12 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 180 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 141,746 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.01 (-0.00-0.01) | 6 more per 1000 (1 fewer to 13 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 1 year) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 141,746 | 1,418,613 | RD0.00 (-0.00-0.01) | 4 more per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 11 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

The majority of evidence did not differentiate between a reduction in ED opening hours, ED closures, or whole hospital closures.

Table 15Clinical evidence profile: 10-30 minutes increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Increased driving time | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (follow-up 7 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 26,817 | 1,418,613 | RD −0.01 (-0.02-0.00) | 6 fewer per 1000 (from 16 fewer to 3 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 30 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 26,817 | 1,418,613 | RD −0.01 (-0.02-0.00) | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 21 fewer to 8 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 90 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 26,817 | 1,418,613 | RD −0.01 (-0.02-0.01) | 6 fewer per 1000 (from 21 fewer to 8 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 180 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 26,817 | 1,418,613 | RD −0.00 (-0.02-0.01) | 3 fewer per 1000 (from 17 fewer to 12 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 1 year) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 26,817 | 1,418,613 | RD −0.01 (-0.02-0.01) | 7 fewer per 1000 (from 22 fewer to 8 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

The majority of evidence did not differentiate between a reduction in ED opening hours, ED closures, or whole hospital closures.

Table 16Clinical evidence profile: Over 30 minutes increased driving time to ED versus no increase in driving time to the ED

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Increased driving time | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Mortality (follow-up 7 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 3187 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.02 (-0.01-0.05) | 17 more per 1000 (from 15 fewer to 49 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 30 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 3187 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.01 (-0.03-0.06) | 12 more per 1000 (from 31 fewer to 56 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 90 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 3187 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.03 (-0.02-0.08) | 26 more per 1000 (from 24 fewer to 76 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 180 days) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 3187 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.04 (-0.01-0.09) | 45 more per 1000 (from 5 fewer to 95 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

| Mortality (follow-up 1 year) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | observational studies | serious1 | no serious inconsistency | serious2 | no serious imprecision | none | 3187 | 1,418,613 | RD 0.06 (0.01-0.11) | 57 more per 1000 (from 7 to 106 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

- 1

All non-randomised studies automatically downgraded due to selection bias. Studies may be further downgraded by 1 increment if other factors suggest additional high risk of bias, or 2 increments if other factors suggest additional very high risk of bias.

- 2

The majority of evidence did not differentiate between a reduction in ED opening hours, ED closures, or whole hospital closures.

Appendix G. Excluded clinical studies

Table 17Studies excluded from the clinical review

| Study | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| Anon 20151 | Protocol only |

| Congdon 20012 | Statistical model: no interventions/outcomes of interest |

| El sayed 20125 | Incorrect intervention: Consolidation of 2 EDs to a single site |

| Fisher 20006 | Study design (descriptive) |

| Mitchell 200810 | Study design (descriptive) |

| Shen 2016 | No extractable data |

| Sun 200612 | Whole hospital closing |

| Teljeur 200413 | Statistical model: no interventions/outcomes of interest |

Appendix H. Excluded health economic studies

No health economic studies were excluded from this review.

- Emergency department opening hours - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16...Emergency department opening hours - Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...