NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Guideline Centre (UK). Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 94.)

Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation.

Show details12. Alternatives to hospital care

12.1. Introduction

There is an increasing evidence base to support the treatment of some acute medical illnesses using ambulatory care, that is, where patients receive treatment whilst staying in their own home or care home after a clinical assessment. In addition, there is an increasing recognition that not all patients have a good experience of hospital bed based care, and that treatment in the usual place of residence would be preferable if safe to do so with an appropriate care model in place.

Whilst there are policy statements from national bodies that are supportive of greater provision of alternatives to hospital care for acute medical illness, there is current uncertainty over the most clinically and cost-effective models of alternatives to hospital care.

12.2. Review question: Does community-based intermediate care improve outcomes compared with hospital care?

For full details see review protocol in Appendix A.

Table 1

PICO characteristics of review question.

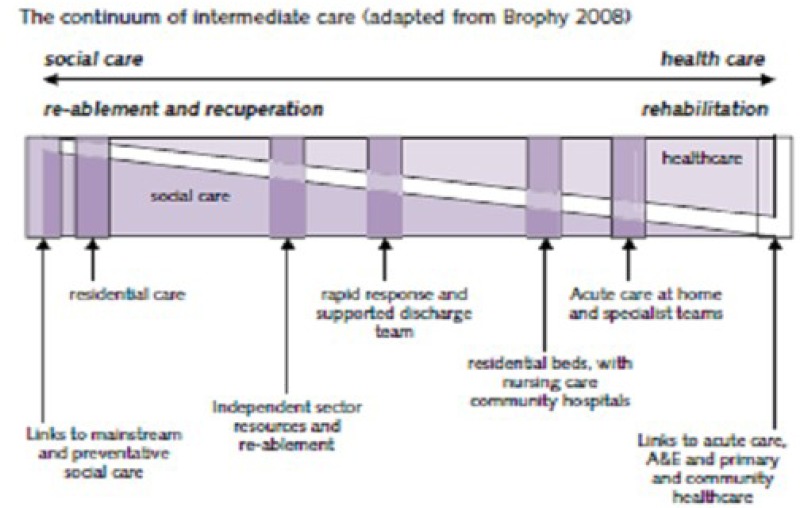

12.2.1. Definitions of the different alternatives to hospital care evaluated in this review

12.2.1.1. Intermediate Care (IC)

The development of IC services was set out in 2001 within the National Service Framework for Older People. The aims of IC were stated as being to:

- promote faster recovery from illness,

- support timely discharge from hospital,

- prevent unnecessary acute hospital admission,

- maximise independent living.

The expectation was of multi-agency working based on comprehensive geriatric assessment, with short-term interventions to enable users to remain or resume living at home.

Definition of intermediate care

The definition of intermediate care provided in the Department of Health paper ‘Intermediate Care - Halfway Home’80 was used; “a range of integrated services to promote faster recovery from illness, prevent unnecessary acute hospital admission and premature admission to long-term residential care, support timely discharge from hospital and maximise independent living”. The guidance makes clear that intermediate care services involve multi-disciplinary team working. Although homecare reablement is included within intermediate care services in some areas, services that do not have a clinical health element are not included.

The National Intermediate Care Audit demonstrates that intermediate care does increase the likelihood of returning home, improve the ability to perform activities of daily living and also increases the achievement of person specific goals. However, there is significant variation in delivery between regions throughout England and unfortunately at present it is not making a difference to the whole-system due to the lack of capacity within the service.214

Classification of Intermediate Care Schemes (as taken from the Department of Health ‘Audit of Intermediate Care’, 2008)

i. Home from hospital

A home from hospital scheme generally aims to provide short-term post-discharge care at a more intensive level than would normally be provided by professionals such as District Nursing. Home from hospital schemes are generally delivered in the user’s own home and led by nursing staff, sometimes with input from medical and allied health professionals.

ii. Rapid response schemes

Rapid response schemes generally aim to support a user in their own home or other location either as a means of preventing admission or as a means of facilitating discharge from the acute hospital sector. Usually led by either a nurse or allied health professional, rapid response schemes can cover a wide range of interventions including administration of intravenous therapies, peg tube and catheter replacement, crisis psychiatric care and provide enhanced care to palliative care patients.

iii. Step up/down schemes

Step up/down schemes usually provide care in a setting other than an acute hospital and this can include a residential or, more usually, a nursing home. Time limited in nature, these schemes aim to either prevent admission to hospital, or aid in the discharge and transfer back home from hospital. Step up/down schemes can be aimed at similar patients to both rapid response and rehabilitation. However, normally the users require more intensive therapy or continuous monitoring than could be provided in their own home.

iv. Rehabilitation schemes

The delivery of community rehabilitation is cognisant with the role of intermediate care which has been promoted by the Department of Health. Rehabilitation is defined as “a process aiming to restore personal autonomy to those aspects of daily life considered most relevant by patients and service users, and their family carers” (Kings Fund, 1998). It is believed that this form of care will reduce the burden on the NHS through the promotion of independence.

Rehabilitation schemes usually provide time limited therapy for patients who require on-going allied health support (generally physiotherapy or occupational therapy) to regain maximum independence. Users of rehabilitation schemes will often have sustained some form of fracture and may also have undergone surgery. Rehabilitation schemes can be delivered by a multi-disciplinary team, but are often led by physiotherapists and/or occupational therapists. These schemes may be longer-term in nature than other types of schemes.

Rehabilitation is defined as the process of restoration of skills by a person who has had an illness or injury so as to regain maximum self-sufficiency and function in a normal or as near normal manner as possible. Rehabilitation is a process aiming to restore personal autonomy to those aspects of daily life considered most relevant to patients, service users and their carers. It can be delivered at a community hospital, residential home or within a patient’s own home.

v. Stroke schemes

Stroke schemes tend to provide a high level of support for those patients who have undergone a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and to provide a high level of rehabilitation, usually in the users own home, to assist them in gaining an increased level of independence. Stroke schemes can be delivered by a multi-disciplinary team that includes medical, nursing, allied health and social work, and also can include the assistance of generic rehabilitation assistants (covering physiotherapy and occupational therapy). These schemes may be longer-term in nature than other types of schemes.

vi. Community hospital schemes

Community hospital schemes usually provide acute hospital ward type care, but generally under the management of GPs rather than consultants. Community hospital schemes can provide nursing, rehabilitation or step up/down type care and are generally aimed at those users who require a high level of supervision or the administration of medicines or interventions which would not be suitable for a nursing home or a users’ own home setting.

vii. Miscellaneous schemes

These schemes included a range of schemes which did not directly fit into one of the classifications previously described. They included an ED assessment team, a twilight nursing team, and a long-term behaviour support team. It could be debated whether these schemes can truly be classified as intermediate.

Within the Intermediate tier there is distinction between:

- viii.

Enabling Homecare - which provides the fundamental building block of a care system where optimised independence and choice is a primary goal. This is aimed at ensuring such skills are maintained by the individual and will be found across the whole care system including any homecare delivered as part of an intermediate tier.

- ix.

Reablement - for people with poor physical or mental health or disability where there is potential to improve independence and choice by learning or re-learning the skills necessary for daily living; and:

When referring to reablement in this context it is also helpful to distinguish between:

- Intake reablement - where all new referrals to adult social services (in particular home care) are considered for reablement; and

- Targeted reablement - where referrals to reablement are received from specific sources, normally hospital discharge or to prevent hospital admission.

- x.

Hospital-at-home care is generally defined as the community based provision of services usually associated with acute inpatient care.

“Hospital-at-home” programs are defined by the provision, in patients’ own homes and for a limited period, of a specific service that requires active participation by health care professionals. The care tends to be multidisciplinary and may include technical services, such as intravenous services.

Many disparate models have been developed under the hospital-at-home label, leading to difficulties in evaluating their effectiveness.

Key features of the Johns Hopkins “hospital-at-home” model:

- A substitutive model providing hospital-level care for patients living in a specified geographic catchment area delineated by 30 minute travel time.

- Eligible patients are those with certain acute illnesses that require hospital-level care who also meet previously validated medical eligibility criteria.

- Robust input from physicians (at least daily visits and 24 hour coverage) and nurses (initial continuous nursing care following by intermittent visits and 24 hour coverage).

- Patient retains inpatient status and the hospital or health system retains responsibility for the acute care episode.

- Care is provided in a coordinated manner similar to that in an inpatient ward.

xi. The Virtual Ward

Virtual wards are a form of preventive hospital-at-home for patients at high predicted risk of unplanned hospital admission.

A model of home-based coordinated care with the aim of reducing hospital admissions in a relatively low-cost manner. The “virtual ward” program provides multidisciplinary case management services to people who have been identified, using a predictive model, as high risks for future emergency hospitalisation. Virtual wards use the systems, staffing and daily routine of a hospital ward to deliver preventive care to patients in their own homes. The Virtual Wards work just like a hospital ward, using the same staffing, systems and daily routines, except that the people being cared for stay in their own homes throughout.

Virtual wards seek to improve integration through a number of strategies, including a shared record, multidisciplinary team meetings (“ward rounds”) and an automated alert system for informing virtual ward staff when a patient accesses another care service, such as attending local ED. Another strategy for promoting integration was to include a social worker as a core member of the virtual ward staff. In this regard, it could be argued that virtual wards are an adaptation of the public health model of chronic disease management described by Kendall and colleagues but rather than integrating health and education, virtual wards instead aim to provide patients with a well organised and coordinated service that crosses the health care and social care sectors.

Community matrons

Community matrons are highly experienced senior nurses who work closely with patients in the community to provide, plan and organise their care. They mainly work with those with a serious long term or complex range of conditions. They therefore have an important role in the management of chronic long-term disease and multi-morbidity. These patients account a large consumption of NHS resources. Clear leadership, guidance and communication between the many services which are involved in the patient care is important to avoid mishaps. Therefore, the community matron is ideally placed to deliver this with the appropriate training and support. This review will determine if increasing the remit of community matrons and increasing the number of locations where community matrons can be accessed improves patient outcomes.

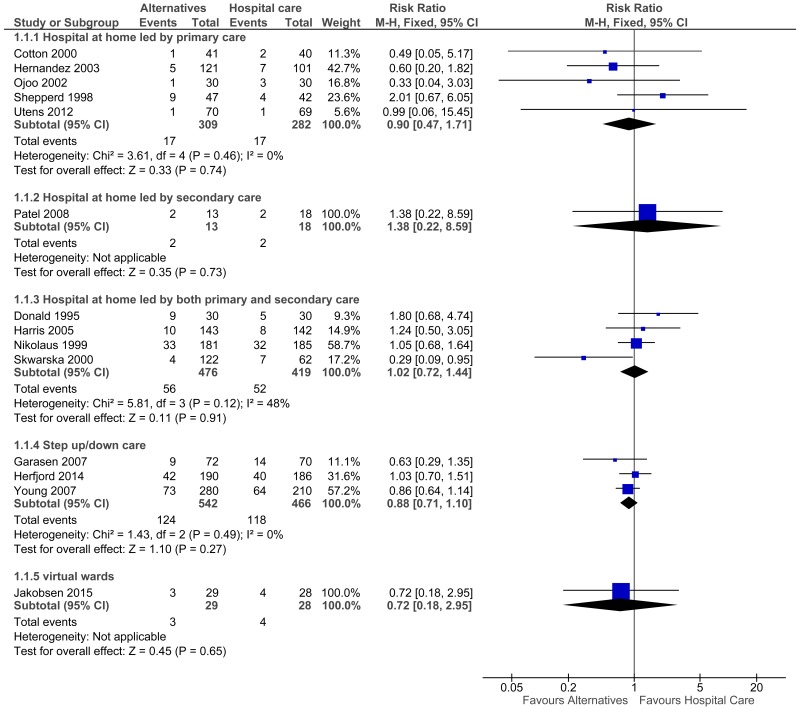

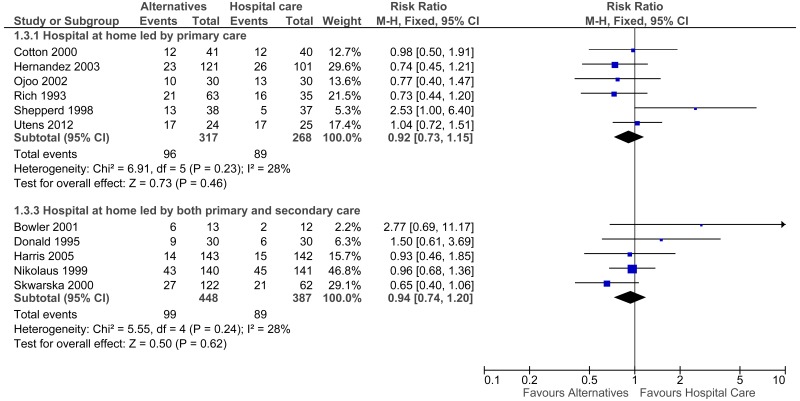

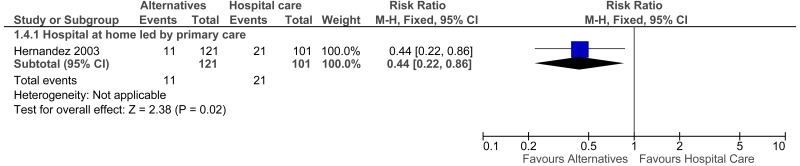

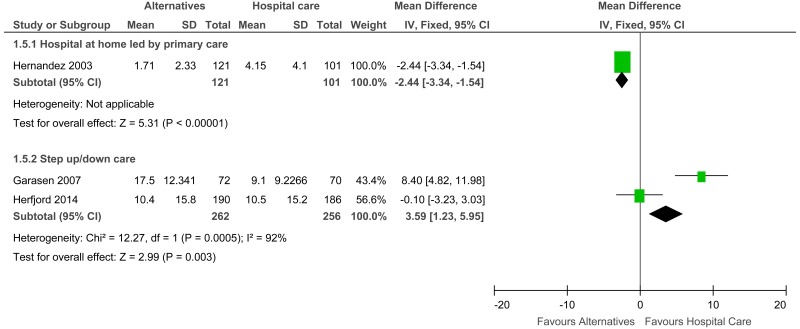

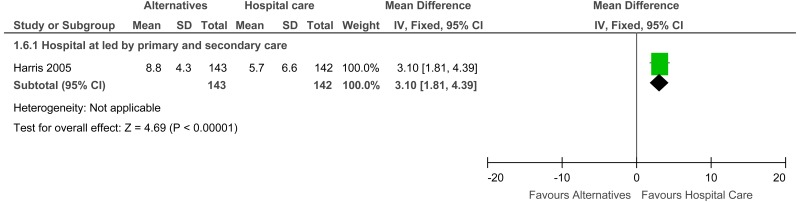

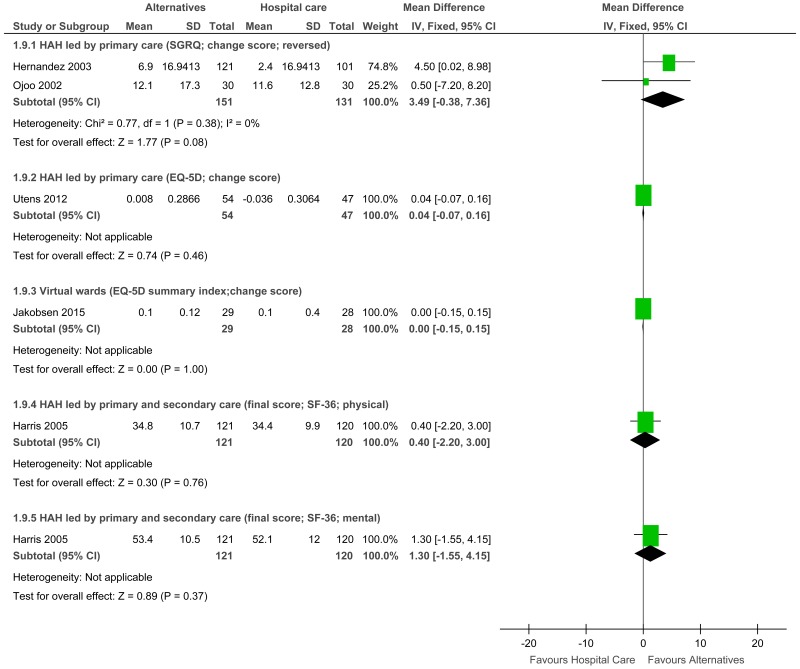

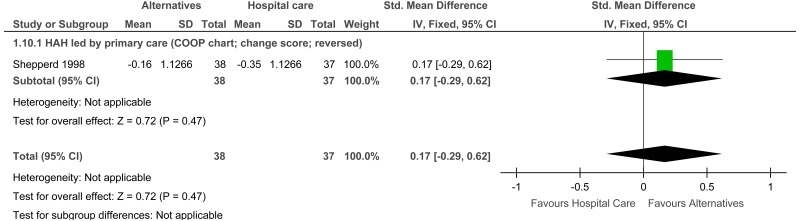

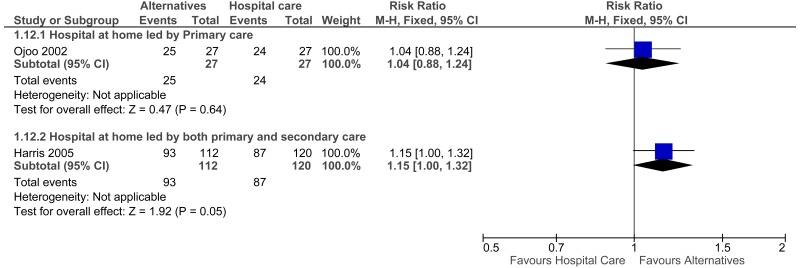

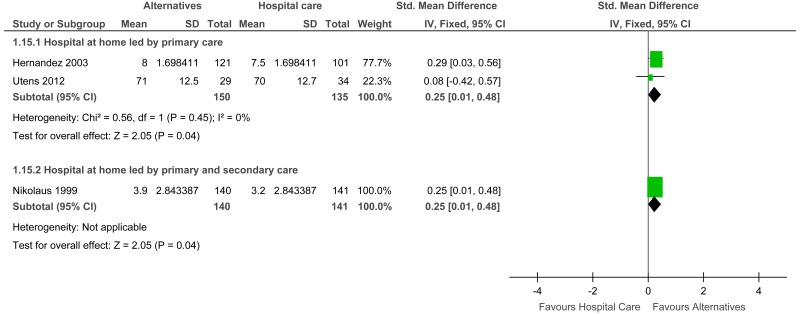

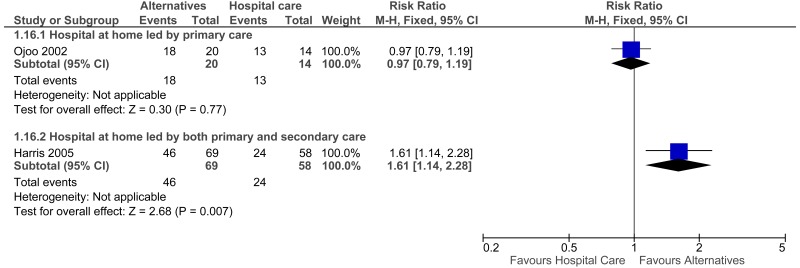

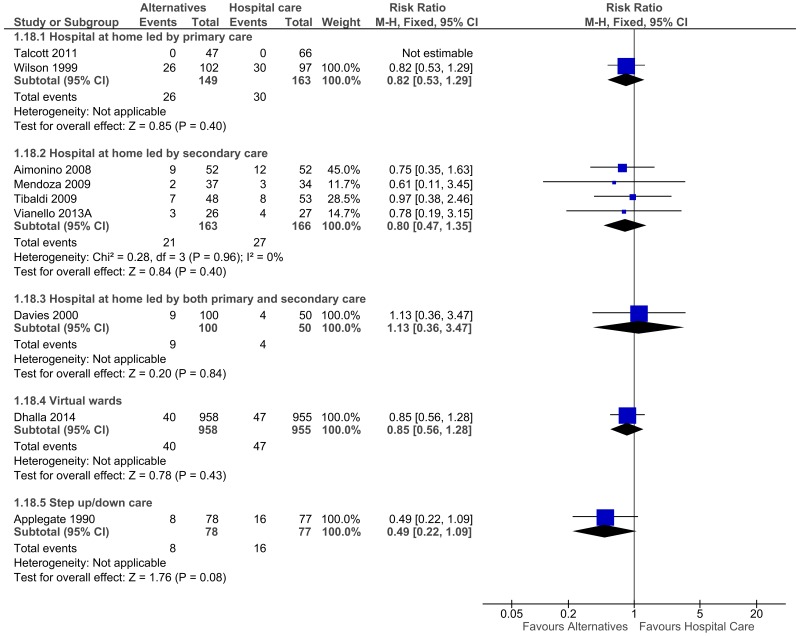

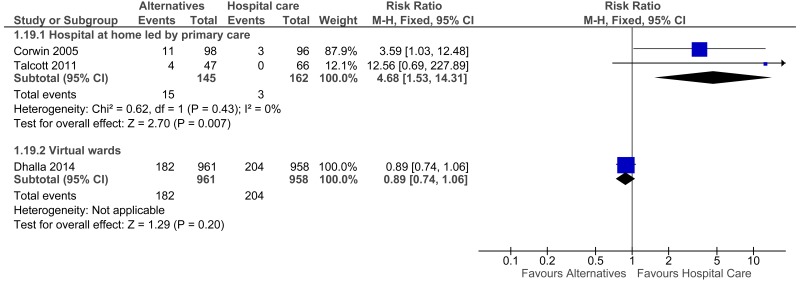

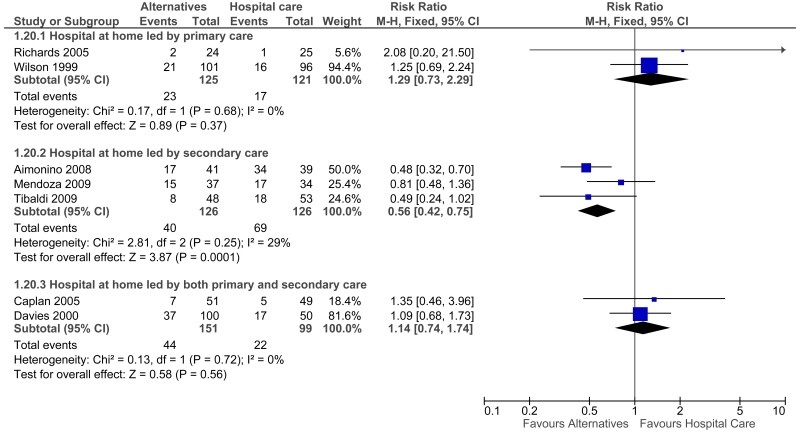

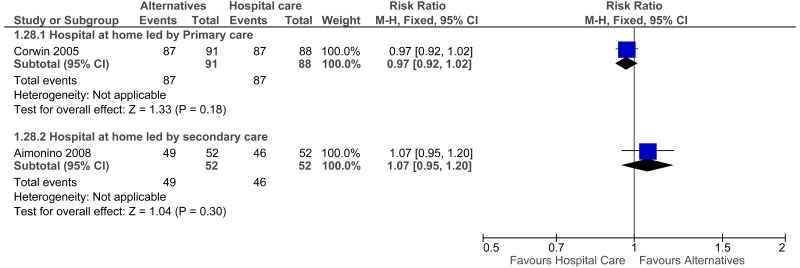

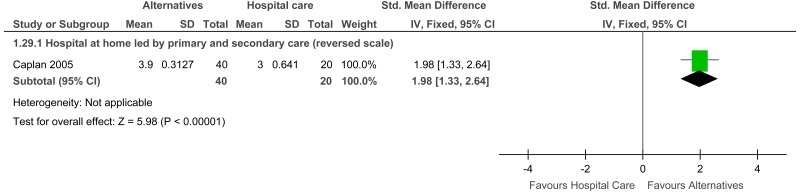

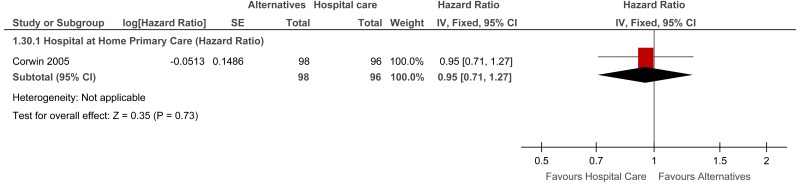

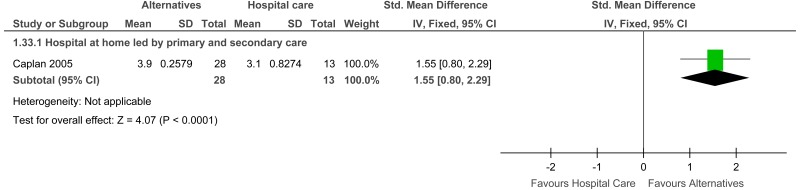

12.3. Clinical evidence

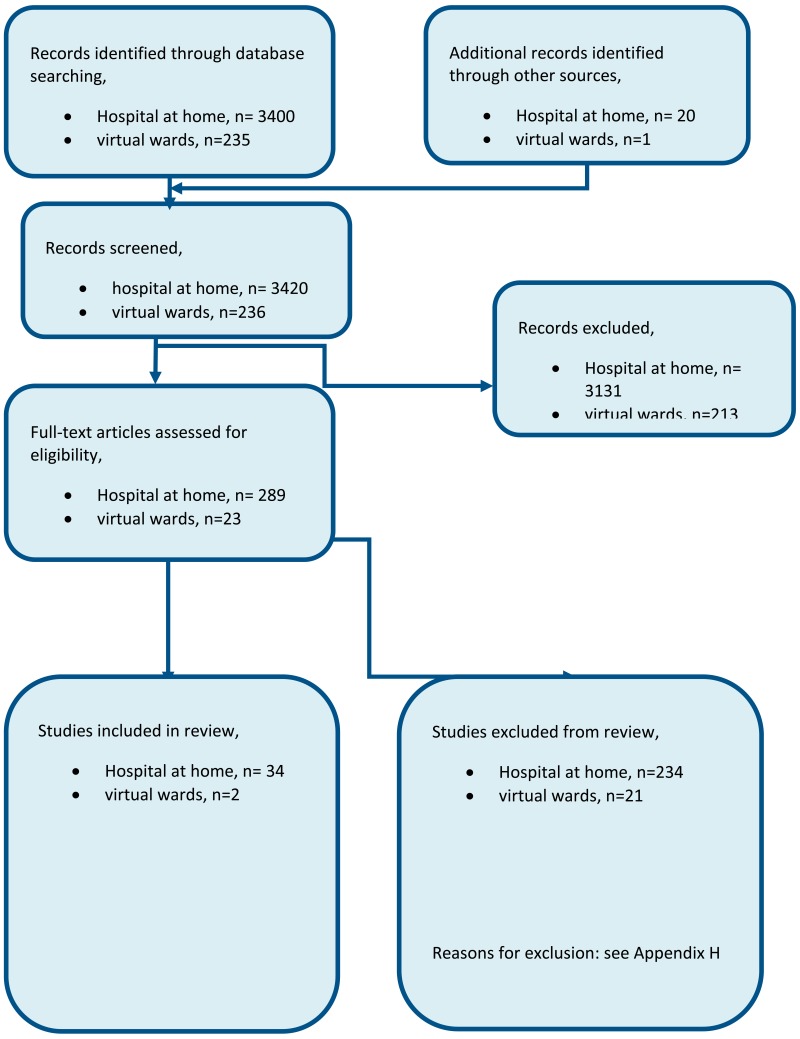

We searched for systematic reviews and randomised trials comparing the effectiveness of alternatives to hospital care (hospital at home, step-up/down care, rapid response schemes and virtual wards) with hospital care to improve outcomes for patients.

Thirty four randomised controlled trials were identified that compared alternatives to hospital care with hospital care. We identified 3 Cochrane reviews evaluating different alternatives to hospital care. All the reviews were assessed for relevance to the review protocol and methodology and were adapted and updated as part of this systematic review. The classification of interventions of the studies included in the Cochrane reviews did not match the definitions of interventions pre-specified by the guideline committee. We re-classified the studies included in the Cochrane reviews according to the definitions of the interventions (see section 12.2.1). Data for the studies presented in the Cochrane reviews has been included in the analysis. We have updated the Cochrane reviews with randomised controlled trials found from the search.

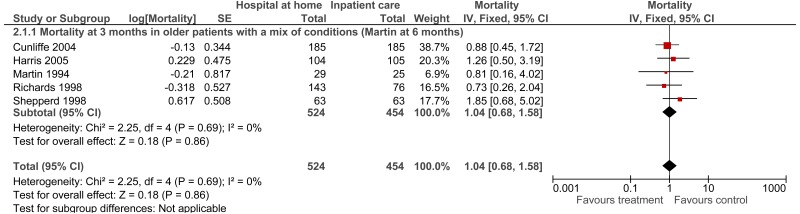

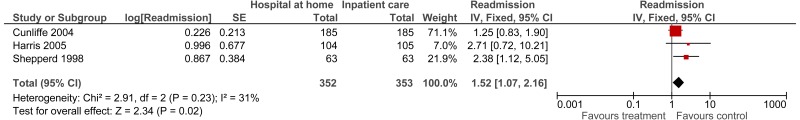

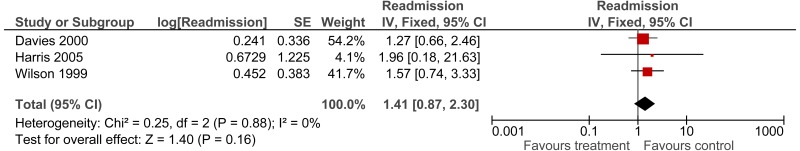

The studies have been classified in 2 strata- admission avoidance and early discharge. Admission avoidance is a service that provides active treatment by health care professionals outside hospital for a condition that otherwise would require acute hospital in-patient admission. Early discharge is a service that provides active treatment by health care professionals outside hospital for a condition that otherwise would require continued acute hospital in-patient care.

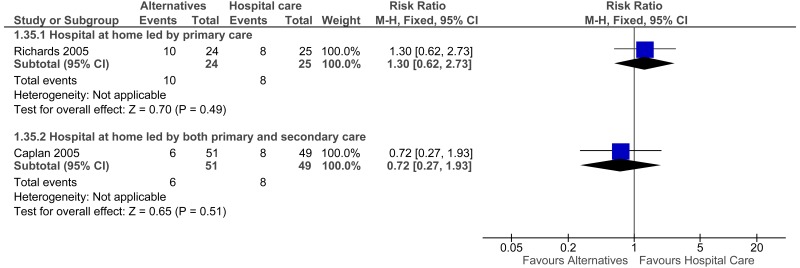

Within each strata, the studies have been grouped according to the type of service provided: hospital at home led by primary care, hospital at home led by secondary care, hospital at home led by primary and secondary care, step-up/down care and virtual wards.

12.3.1. Individual patient data (IPD) analysis

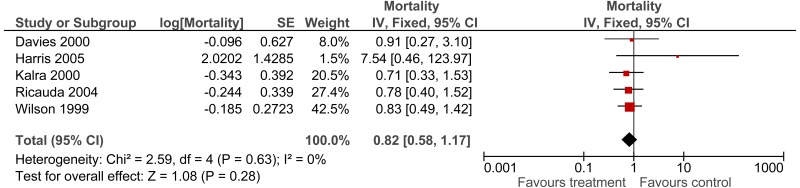

Two Cochrane reviews that met the protocol criteria for the alternatives to hospital care review (1 in the strata for early discharge and 1in the strata for admission avoidance) presented IPD analysis as well as RCT level meta-analysis.

Details of analyses presented in both Cochrane reviews are:

- Review strata 1 –Admission avoidance: Cochrane review on hospital at home admission avoidance. The review includes 10 trials.

- 4 trials were included in the IPD analysis (hazard ratios and log hazard ratios presented for 2 of our protocol outcomes; mortality and admissions).

- All 10 trials were included in the RCT meta-analysis. The RCT meta-analyses included RCT data from the 4 trials included in the IPD meta-analysis.

- Review strata 2- Early discharge: Cochrane review on hospital at home early discharge. The review includes 26 trials.

- 13 trials were included in the IPD analysis (hazard ratios and log hazard ratios presented for 2 of our protocol outcomes; mortality and admissions).

- All 26 trials were included in the RCT meta-analysis. The RCT meta-analyses included RCT data from the 13 trials included in the IPD meta-analysis.

The results of the IPD analysis have been presented as part of this evidence review (see section D.3, Appendix D).

See also the study selection flow chart in Appendix B, study evidence tables in Appendix E, forest plots in Appendix D, GRADE tables in Appendix G and excluded studies list in Appendix H.

12.3.2. Summary of included studies

Following is a summary of the number of studies included for each of the interventions:

- Hospital at home (led by primary care):

- Number of studies identified in Cochrane reviews: 10.

- Number of studies identified from search: 4.

- Hospital at home (led by secondary care):

- Number of studies identified in Cochrane reviews: 4.

- Number of studies identified from search: 3.

- Hospital at home (led by primary and secondary care):

- Number of studies identified in Cochrane reviews: 7.

- Number of studies identified from search: 1.

- Virtual wards:

- Number of studies identified in Cochrane reviews: 0.

- Number of studies identified from search: 2.

- Step up/down care:

- Number of studies identified in Cochrane reviews: 0.

- Number of studies identified from search: 5

See Table 2 below for details of the PICO characteristics of the studies included in the review.

Table 2

Summary of studies included in the review.

Table 3

Summary GRADE profiles for alternatives compared with hospital care.

Narrative findings

Length of hospital stay

Cotton 200067

Mean length of initial admission (range) for the early discharge group 3.2 (1-16) and for conventional management 6.1 (1-13).

Richards 2005242

The median number of days to discharge in the home group was 4 (range: 1-14), compared with 2 (range, 0-10) in the hospital group (p=0.004).

Wilson 1999312

Analyses by intention to treat showed significantly shorter stays in care for the hospital at home group than for the hospital group (median initial stay, 8 days versus 14.5 days, p=0.026); median total days of care in 3 months, 9 days versus 16 days, p=0.031.

Donald 199589

At 6 months the hospital at home total days in hospital (after study entry) of 22.5 (IQR 5-30) and the control group a mean number of days of 20.2 (IQR 8-27).

Applegate 199016

The mean length of stay in the geriatric assessment unit was 23.6 (+/-13.2) days. For the high risk stratum, the average stay was 28.6 (+/-14.4days) and for the lower risk stratum it was 21.1 (+/-11.9) days.

Zimmer 1985325

Mean length of hospital stay during first 6 months for intervention (n=81) was 12.6 days and for control was 14.3 days.

Emergency department visits

Aiken 20066

In the 6 months prior to the onset of PhoenixCare intervention, PhoenixCare participants averaged 0.12 emergency department visits per month (SD=0.18). Control participants averaged 0.11 emergency department visits per month (SD=0.02). This level of utilisation remained essentially unchanged during the intervention, with averages of 0.11 (SD=0.34) and 0.10 (SD=0.31) visits per month for Phoenix Care and control participants, respectively.

Zimmer 1985325

Mean ED visits per patient per month for days at risk in the first 6 months of study; intervention (n=81) 0.26 and control (n=75) 0.05.

Quality of Life

Applegate 199016

The group assigned to the geriatric assessment unit had significantly more improvement (p<0.05) than the control group in regard to 3 basic self-care activities (bathing, dressing and the ability to transfer) during the 6 months after randomisation.

Patient satisfaction

Richards 2005242

Patient satisfaction with medical and nursing care was high in both groups, but significantly higher in the home care group (p=0.001). In the home care group, all patients reported that they were ‘very happy’ with their care. In the hospital care group, 60% were ‘very happy’, 32% ‘quite happy’ and 8% ‘neither happy nor unhappy’.

Wilson 2002314

Patient satisfaction was greater with Hospital at Home than with hospital. Reasons included a more personal style of care and a feeling that staying at home was therapeutic. Carers did not feel that Hospital at Home imposed an extra workload.

Skwarska277

Replies to the questionnaires on satisfaction with the service were received from 69% of the patients treated at home, 95% of whom said they were ‘completely satisfied’ with the services and 90% felt they had been cared for just as well or better at home than they would have been in hospital.

Young 2007322

The reported patient satisfaction was similar for both groups. At 1 week after hospital discharge, the community hospital group showed greater satisfaction with the statement ‘I am happy with the amount of recovery I have made’ (odds ratio=2.12, 95% CI=1.30-3.46; p=0.004).

Zimmer 1985325

Mean unadjusted patient satisfaction scores at 6 months for the community palliative group was 95.0 (n=31; p=not statically significant) and for the control group 89.3 (n=22; p=not statically significant).

Carer satisfaction

Donald 199589

There were 13 HAH carers and 7 control group carers, all of whom were interviewed at each assessment. A large majority of carers were happy with the timing of discharge. Questions ratings carer’s opinions of how good they were at the caring role, and how well they were coping, were answered similarly with 2 HAH carers and 1 control group carer admitting difficulties in coping. No clear differences between the groups emerged, but the numbers were small.

Carer stress

Tibaldi 2009296

The level of stress of the caregiver was high on admission in both groups but more severe in caregivers of Geriatric Home Hospital Service (relative stress scale score, 25.4 [16.6] versus 17.1 [10.8] in the general medical ward group; p=0.003).

12.4. Economic evidence

Twelve economic evaluations, published in 13 papers, relating to hospital-at-home, virtual wards and step-up/step down community care have been included in this review.7,23,102,118,202,204,229,235,242,288,292,296,304 One study204 was relevant to all 3 of these strata.

These are summarised in the economic evidence profile tables (Table 4, to Table 10) and the economic evidence tables in Appendix E.

Table 10

Economic evidence profile: Rapid response scheme versus usual inpatient care.

One study239 of hospital-at-home was excluded due to very serious limitations and three more17,165,225 were selectively excluded because there was better quality evidence available. One paper relating to step-up/step-down interventions was identified but was excluded due to the availability of more applicable evidence.221 Another paper relating to virtual wards was identified but excluded due to serious limitations.186 All of these are listed in Appendix H, with reasons for exclusion given.

The economic article selection protocol and flow chart for the whole guideline can found in the guideline’s Appendix 41A and Appendix 41B.

Table 4

Economic evidence summary - Hospital at home versus inpatient care.

Table 5

Economic evidence profile: Hospital at home versus inpatient hospital care – Admission avoidance.

Table 6

Economic evidence profile: Hospital at home versus inpatient hospital care – Early discharge.

Table 7

Economic evidence profile: Hospital at home versus inpatient hospital care – Both admission avoidance and early discharge.

Table 8

Economic evidence profile: Step up/Step-down care versus inpatient hospital care.

Table 9

Economic evidence profile: Virtual wards care versus inpatient care.

12.5. Evidence statements

12.5.1. Clinical

Strata – Early discharge

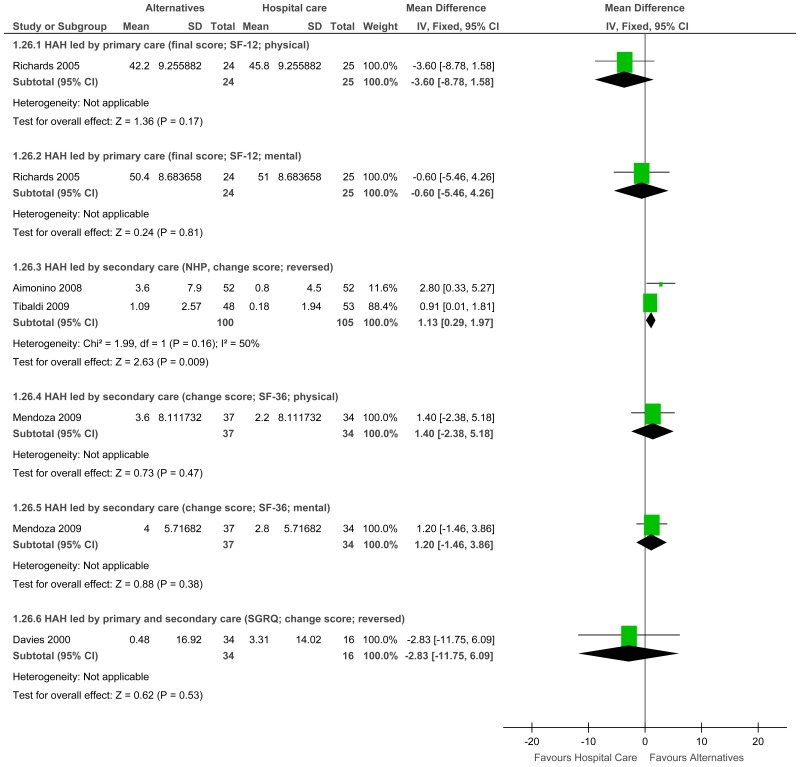

Six studies comprising 591 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by primary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary care may provide a benefit in reduced admissions (6 studies, low quality), presentations to ED (1 study, moderate quality), hospital length of stay (1 study, moderate quality), quality of life (various scores reported total of 5 studies, low to moderate quality) and patient satisfaction (continuous outcome: 2 studies, high quality and dichotomous; 1 study, moderate quality). The evidence suggested that there was no effect on mortality (5 studies, low quality) and there was a possible reduction in carer satisfaction (1 study, moderate quality) in hospital at home led by primary care compared to hospital care.

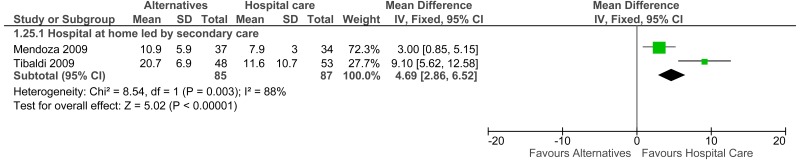

One study comprising 197 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by secondary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by secondary care may provide a benefit in reduced re-admissions (1 study, very low quality). There was a possible increase in mortality (1 study, very low quality) in hospital at home led by secondary care compared to hospital care.

Five studies comprising 895 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence showed that hospital at home led by primary and secondary care provided a benefit in reduced admissions (5 studies, moderate quality), and carer satisfaction (1 study, moderate quality). The evidence suggested that there was no effect on mortality (4 studies, very low quality). There was an increase in re-admissions (1 study, moderate quality) and length of stay (1 study, moderate quality) in hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care compared to hospital care. Evidence on quality of life showed no difference in 1 study and an improvement in another study (both moderate quality). Similarly, patient satisfaction in 1 study showed no difference the other showed an improvement (both high quality).

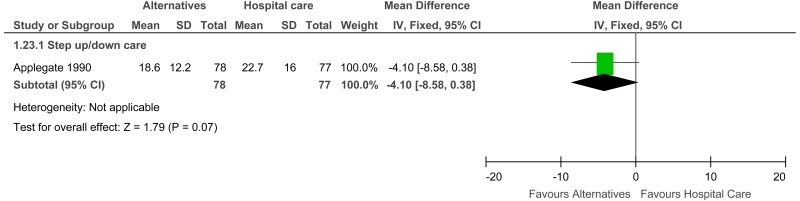

Three studies comprising 1008 people evaluated the role of step-up/down care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that step-up/down care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (3 studies, low quality) and readmissions compared to hospital care. There was a suggested increase in length of stay (2 studies, very low quality) in step-up/down care compared to hospital care.

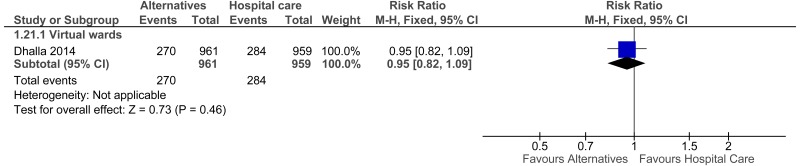

One study comprising 57 people evaluated the role of virtual wards in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that virtual wards may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (1 study, very low quality). The evidence suggested that there was no effect on quality of life (1 study, moderate quality) in virtual wards compared to hospital care.

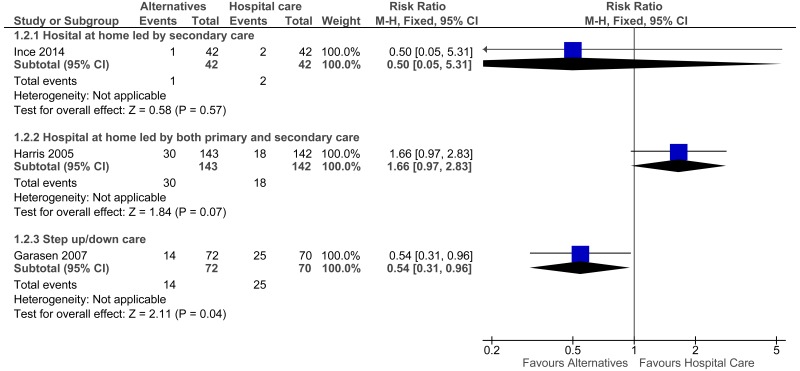

Strata – Admission avoidance

Four studies comprising 571 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by primary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (2 studies, moderate quality) and quality of life on SF-12 physical scores ((1 study, moderate quality). The evidence suggested that there was no effect on days to discharge (1 study, low quality). There was an increase in readmissions under 30 days (2 studies, high quality), adverse events (1 study, low quality) and reduced patient satisfaction (1 study, high quality) in hospital at home led by primary care compared to hospital care. No difference was identified for admissions over 30 days (2 studies, low quality) and quality of life on SF-12 mental scores (1 study, low quality).

Four studies comprising 329 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by secondary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by secondary care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (4 studies, low quality), reduced admissions after 30 days (3 studies, low quality), improved patient satisfaction (1 study, high quality) and quality of life (3 different scores reported, low to moderate quality). The evidence suggested that there was increased length of stay (2 studies, low quality) in hospital at home led by secondary care compared to hospital care.

Two studies comprising 252 people evaluated the role of hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary and secondary care may provide a benefit in improved patient satisfaction (1 study, low quality), carer satisfaction (1 study, high quality) and reduced adverse events (1 study, low quality). There was a possible increase in mortality (1 study, low quality), admissions (2 studies, low quality) and reduced quality of life (1 study, moderate quality) in hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care compared to hospital care.

One study comprising 155 people evaluated the role of step-up/down care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested step-up/down care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality (1 study, moderate quality) and length of stay (1 study, low quality) compared to hospital care.

One study comprising 1920 people evaluated the role of virtual wards in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that virtual wards provide a benefit in reduced mortality (1 study, low quality), reduced re-admissions (1 study, high quality) and presentations to ED (1 study, high quality) compared to hospital care.

12.5.2. Economic

Four cost-effectiveness analyses and one cost-utility analysis found that hospital at home led by secondary care dominated inpatient care. One cost analysis found it to be cost saving (cost difference: £600 per patient) and one cost effectiveness analysis showed that inpatient care was more costly and more effective (£46,000 per extra patient with no decline in respiratory function). These studies were assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

One cost-utility analysis found that inpatient care was not cost effective at a threshold of £20,000 per QALY compared with hospital at home led by primary care but it was cost-effective at a threshold of £30,000 per QALY gained (ICER:£24,000 per QALY gained). One cost-effectiveness analysis found that inpatient care was dominated. One cost-effectiveness analysis found that inpatient care was more effective but more costly (£4,000 per adverse event avoided). These studies were assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

One cost-effectiveness analysis found that hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care dominated inpatient care. This study was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

One cost-utility analysis found that step up/step down was cost effective compared with inpatient care (ICER: £16,300 per QALY gained). One cost comparison study found that it was cost saving (cost difference: £115 per patient). These studies were assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

One cost comparison study found that virtual wards are cost saving (cost difference: £404 per patient). This study was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

One cost comparison study found that rapid response and early supported discharge was cost saving (cost difference: £116 per patient). This study was assessed as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations.

12.6. Recommendations and link to evidence

| Recommendations |

|

| Research recommendations | - |

| Relative values of different outcomes |

Quality of life, mortality, avoidable adverse events, patient and/or carer satisfaction and number of admissions to hospital were considered by the committee to be critical outcomes. Number of GP presentations, readmission, length of hospital stay and number of presentations to the Emergency Department were considered by the committee to be important outcomes. |

| Trade-off between benefits and harms |

This review examined evidence for the following interventions:

There was evidence from 36 RCTs comparing hospital at home (led by primary care, secondary care or both primary and secondary care), step-up/down care and virtual wards. The studies were categorised into 2 strata: hospital at home services focussing on early discharge and hospital at home services focussing on admission avoidance. Within each category, the evidence was classified into hospital at home led by primary care, hospital at home led by secondary care, hospital at home led by primary and secondary care, step up/down care and virtual wards. Stratum – Early discharge Hospital at home led by primary care Six studies evaluated hospital at home led by primary care compared to usual hospital care. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary care may provide a benefit in reduced admissions, presentations to ED, hospital length of stay, quality of life and patient satisfaction. The evidence suggested that there was no effect on mortality and there was reduced carer satisfaction in hospital at home led by primary care compared to usual hospital care. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, GP presentations or readmissions. Hospital at home led by secondary care Two studies evaluated hospital at home led by secondary care compared to usual hospital care. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by secondary care may provide a benefit in reduced re-admissions. However, there was a possible increase in mortality. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient satisfaction, length of stay, length of stay in programme, presentation to ED, admissions and GP presentations. Hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care Five studies evaluated hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care compared to usual hospital care. The evidence showed a benefit in reduced admissions, and carer satisfaction compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that there was no effect on mortality. There was an increase in re-admissions (30 days) and length of stay (days in treatment) in hospital at home led primary and secondary care compared to usual hospital care. Evidence on quality of life and on patient satisfaction was either neutral or suggested a trend for improvement. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, length of stay in programme, presentation to ED and presentation to GP. Step-up/down care Three studies evaluated step-up/down care compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that step-up/down care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality and readmissions compared to hospital care. There was a suggested increase in length of stay (initial inpatient days) in step-up down care compared to hospital care. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient satisfaction, length of stay in programme, number of presentations to ED, number of GP presentations and admissions. Virtual wards One study evaluated virtual wards compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that virtual wards may provide a benefit in reduced mortality compared to hospital care but there was no effect on quality of life. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, patient satisfaction, length of hospital stay, length of stay in programme, number of presentation to ED, number of admissions to hospital, number of GP presentation and readmission. Stratum – Admission avoidance There was variation in how these diverse admission avoidance schemes operated. Some schemes admitted patients directly from the community and some from the emergency department. The majority of the trials included in the admission avoidance strata recruited elderly patients with medical events like stroke and COPD requiring admission to hospital. The committee considered that avoiding readmission was likely to be particularly important for people with chronic conditions as in this group hospital admission might have a disproportionately adverse effect on psychological wellbeing and independence. Hospital at home led by primary care Four studies evaluated the role of hospital at home led by primary care in adults and young people at risk of an AME, or with a suspected or confirmed AME. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality and quality of life on SF-12physical scores. The evidence suggested that there was no effect on days to discharge. There was an increase in readmissions under 30 days, adverse events and reduced patient satisfaction in hospital at home led by primary care compared to hospital care. No difference was identified for admissions over 30 days and quality of life on SF-12 mental scores. Hospital at home led by secondary care Four studies evaluated hospital at home led by secondary care compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by secondary care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality, admissions (>30 days), improved patient satisfaction and quality of life compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that there was increased length of stay in hospital at home led by secondary care compared to hospital care. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, length of stay in programme, number of presentations to ED, number of GP presentations and readmission. Hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care Two studies evaluated hospital at home led by both primary and secondary care compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that hospital at home led by primary and secondary care may provide a benefit in improved patient satisfaction, carer satisfaction and reduced adverse events compared to hospital care. There was a possible increase in mortality, admissions (>30 days) and reduced quality of life in hospital at home led by primary and secondary care compared to hospital care. No evidence was identified for length of stay, length of stay in programme, number of presentations to ED, number of GP presentation and readmission. Step-up down care One study evaluated step-up/down care compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested step-up/down care may provide a benefit in reduced mortality and length of stay compared to hospital care. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient satisfaction, length of stay in programme, number of presentations to ED, number of GP presentations and readmissions. Virtual wards One study evaluated virtual wards compared to hospital care. The evidence suggested that virtual wards provide a benefit in reduced mortality, reduced re-admissions (30 days) and presentations to ED compared to hospital care. No evidence was identified for avoidable adverse events, quality of life, patient satisfaction, length of hospital stay, length of stay in programme, number of admissions to hospital and number of GP presentations. Rapid response schemes No evidence was available to evaluate rapid response schemes. Overall The committee chose to recommend alternatives to hospital care given the potential benefits in patient and carer satisfaction, facilitation of early discharge and prevention of hospital admission, if there is a discussion of the potential benefits and risks with the patient and their carer. The committee also concluded that RCT evidence supported the concept that, with appropriate patient selection, hospital at home schemes could be considered safe. The committee discussed what type of alternatives to hospital care should be recommended: hospital at home, community-based intermediate care or community-based care. This review did not search for data that specifically compared different schemes. The committee agreed that service development would need to be undertaken collaboratively between primary and secondary care. The committee noted that ‘hospital-at-home’ was not easily defined and that there were some regions in which community-based intermediate care could differ. Therefore, the committee chose to recommend community-based intermediate care generally, rather than specifying the precise content of the various interventions. The committee also noted that there were many different schemes and with different names, which could be confusing for the patient as well as the service provider. It was however felt that, despite this, if one concentrated on what each individual scheme provided to the patient then they were very similar. They generally involved nurses and/or therapists with medical support providing nursing care, rehabilitative therapy, education and support to a patient in the community with an aim to promote independence, prevent admission and facilitate discharge. Indeed, it was felt that if the names of the services were simplified under 1 heading, it would be much easier to understand and the focus could be on the level of support and care the patient required. The committee wished to clarify that community-based care should only be provided where equivalent care could be provided in a non-hospital based setting and following appropriate risk stratification using appropriate diagnostics, clinical presentation, patient preference, history and safety netting. The committee noted that there were some groups of people (for example, people with life threatening conditions such as acute myocardial infarction) in whom the provision of care in a non-hospital based setting was not appropriate in the acute stage. |

| Trade-off between net effects and costs |

Hospital at home Eleven economic evaluations were included covering the 3 models of hospital at home (secondary care-led, primary care-led and mixed model). This evidence consistently showed that hospital at home schemes can be provided at a lower cost for a variety of patient groups. Seven studies showed that hospital at home was dominant when compared to inpatient care, where it appeared to improve outcomes as well as lower costs. This was the case for all three of the full economic evaluations of interventions combining both admission avoidance and early discharge. In the remaining three studies, the health benefit for hospital care was small and did not appear to be cost effective. Cost savings were greatest for those interventions that included admission avoidance. The committee highlighted the importance of assessing patients’ risk before referring them to be cared for under a hospital-at home service, which was in line with the inclusion criteria of the included studies. The committee also highlighted the importance of providing 24-hour access to care for hospital-at-home patients as currently available hospital-at-home services differ in terms of the hours that they operate. For example, the committee noted that most of the included studies provided 24-hour access to the service, either in person or via phone. The provision of these services across a 24 hour, 7-day period may affect cost in terms of both staff costs as well as its impact on patients’ safety and efficacy. Anecdotally, the committee noted that many schemes provided extended day hours or 24 hours a day but services are shared with other out-of-hour services. Step up/step-down models One economic evaluation showed that care in a community hospital was cost effective compared to inpatient care, at a cost of £16,400 per QALY gained, which is below the NICE threshold. A cost simulation study showed that long-term costs were lower but it would take more than 5 years to break even because of the time taken to build up credibility and reach optimal scale. Virtual wards One cost simulation study showed that long-term costs were lower but it would take about 5 years to break even. Rapid response schemes A cost simulation study showed that long-term costs were lower but it would take more than 5 years to break even. |

| Quality of evidence |

Overall, the quality of the evidence was graded from very low to high. Evidence was downgraded and this was mainly due to risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency. The economic evidence for hospital at home was rated as partially applicable with potentially serious limitations, since QALYs were rarely measured, only two studies were set in the UK and the effectiveness evidence was not based on a systematic review. |

| Other considerations |

The committee highlighted that they were aware of observational studies of alternatives to hospital care but wished to prioritise the inclusion of higher quality, RCT evidence for inclusion in the review. The committee emphasised that where possible, decisions about treatment location should be made collaboratively with the patient. It was noted that patient acceptability would need to be determined on a case by case basis. It is important that patients should be involved in discussions of risks and benefits. Overall it was felt the provision of intermediate care as an alternative to hospital admission should be supported and developed in view of the evidence reviewed. It also fits with the NHS Five Year Forward View by providing more care in the community, but supported by primary and secondary care in an integrated way. The health economic data suggests that this model of care may be cost saving which is another important issue for the NHS in the ensuing years. Although it is likely that in the initial phase in development or expansion of schemes they may be costlier and will take some years to break even, and then become cost saving as some of the economic evidence showed. One barrier to the development of this model of care could be the conflict between primary and secondary care. The skills and resources of both sectors and the third sector (voluntary) will need to be harnessed for such models of care to work. It is also important that areas of good practice are shared. Simplification of delivery of intermediate care would also be of use; rather than focussing on the title of the service, it would be better if the needs of the patient are the focus of delivery of care. This would probably allow services between regions to be compared with each other and benchmarking of services. The National Audit of Intermediate Care214 defines intermediate care in 4 categories:

|

References

- 1.

- Swing-beds meet patients needs and improve hospitals cash-flow. Hospitals. 1982; 56(13):39–40 [PubMed: 7084902]

- 2.

- Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Shelby-James T, Rowett D, May F, Samsa GP et al. Delivery strategies to optimize resource utilization and performance status for patients with advanced life-limiting illness: results from the “palliative care trial” [ISRCTN 81117481]. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013; 45(3):488–505 [PubMed: 23102711]

- 3.

- Abou ESG, Dowswell T, Mousa HA. Planned home versus hospital care for preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes (PPROM) prior to 37 weeks’ gestation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014; Issue 4:CD008053. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008053.pub3 [PubMed: 24729384] [CrossRef]

- 4.

- Adib-Hajbaghery M, Maghaminejad F, Abbasi A. The role of continuous care in reducing readmission for patients with heart failure. Journal of Caring Sciences. 2013; 2(4):255–267 [PMC free article: PMC4134146] [PubMed: 25276734]

- 5.

- Adler MW, Waller JJ, Creese A, Thorne SC. Randomised controlled trial of early discharge for inguinal hernia and varicose veins. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1978; 32(2):136–142 [PMC free article: PMC1060932] [PubMed: 98548]

- 6.

- Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006; 9(1):111–126 [PubMed: 16430351]

- 7.

- Aimonino Ricauda N, Tibaldi V, Leff B, Scarafiotti C, Marinello R, Zanocchi M et al. Substitutive “hospital at home” versus inpatient care for elderly patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008; 56(3):493–500 [PubMed: 18179503]

- 8.

- Aimonino N, Molaschi M, Salerno D, Roglia D, Rocco M, Fabris F. The home hospitalization of frail elderly patients with advanced dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2001; 7:19–23 [PubMed: 11431041]

- 9.

- Aimonino N, Salerno D, Roglia D, Molaschi M, Fabris F. The home hospitalization service of elderly patients with ischemic stroke: follow-up study. European Journal of Neurology. 2000; 7:(Suppl 3):111–112

- 10.

- Alder IL, Augenstein LL, Rogerson TD. Gas-liquid chromatographic determination of sodium 5-[2-chloro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy]-2-nitrobenzoate residues on soybeans and foliage, soil, milk, and liver. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1978; 61(6):1456–1458 [PubMed: 569657]

- 11.

- Allen J. Surgical Internet at a glance: the Virtual Hospital. American Journal of Surgery. 1999; 178(1):1 [PubMed: 10456693]

- 12.

- Anderson C, Ni MC, Rubenach S, Clark M, Spencer C, Winsor A. Early supportive discharge and rehabilitation trial in stroke (ESPRIT). Royal Australasian College of Physicians Annual Scientific Meeting. 2000;16

- 13.

- Anderson C, Ni Mhurchu C, Brown PM, Carter K. Stroke rehabilitation services to accelerate hospital discharge and provide home-based care: an overview and cost analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002; 20(8):537–552 [PubMed: 12109919]

- 14.

- Anderson DJ, Burrell AD, Bearne A. Cost associated with venous thromboembolism treatment in the community. Journal of Medical Economics. 2002; 5(1-10):1–10

- 15.

- Andrei CL, Sinescu CJ, Ianula RM. Can be the home care of the heart failure patients a better economic alternative? European Journal of Heart Failure Supplements. 2011; 2011(11):S29

- 16.

- Applegate WB, Miller ST, Graney MJ, Elam JT, Burns R, Akins DE. A randomized, controlled trial of a geriatric assessment unit in a community rehabilitation hospital. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990; 322(22):1572–1578 [PubMed: 2186276]

- 17.

- Armstrong CD, Hogg WE, Lemelin J, Dahrouge S, Martin C, Viner GS et al. Home-based intermediate care program vs hospitalization: cost comparison study. Canadian Family Physician. 2008; 54(1):66–73 [PMC free article: PMC2293319] [PubMed: 18208958]

- 18.

- Askim T, Morkved S, Indredavik B. Intensive motor training combined with early supported discharge after treatment in a comprehensive stroke unit. A randomised controlled trial. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009; 27:(Suppl 6):42 [PubMed: 20558830]

- 19.

- Aujesky D, Roy PM, Verschuren F, Righini M, Osterwalder J, Egloff M et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet. 2011; 378(9785):41–48 [PubMed: 21703676]

- 20.

- Avlund K, Jepsen E, Vass M, Lundemark H. Effects of comprehensive follow-up home visits after hospitalization on functional ability and readmissions among old patients. A randomized controlled study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002; 9(1):17–22

- 21.

- Bai M, Reynolds NR, McCorkle R. The promise of clinical interventions for hepatocellular carcinoma from the west to mainland China. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2013; 11(6):503–522 [PubMed: 23398641]

- 22.

- Bajwah S, Ross JR, Wells AU, Mohammed K, Oyebode C, Birring SS et al. Palliative care for patients with advanced fibrotic lung disease: a randomised controlled phase II and feasibility trial of a community case conference intervention. Thorax. 2015; 70(9):830–839 [PubMed: 26103995]

- 23.

- Bakerly ND, Davies C, Dyer M, Dhillon P. Cost analysis of an integrated care model in the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Respiratory Disease. 2009; 6(4):201–208 [PubMed: 19729444]

- 24.

- Bakken MS, Ranhoff AH, Engeland A, Ruths S. Inappropriate prescribing for older people admitted to an intermediate-care nursing home unit and hospital wards. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2012; 30(3):169–175 [PMC free article: PMC3443941] [PubMed: 22830533]

- 25.

- Balaban RB, Weissman JS, Samuel PA, Woolhandler S. Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: a randomized controlled study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008; 23(8):1228–1233 [PMC free article: PMC2517968] [PubMed: 18452048]

- 26.

- Barnes MP. Community rehabilitation after stroke. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2003; 15(3-4):223–234

- 27.

- Beech R, Russell W, Little R, Sherlow-Jones S. An evaluation of a multidisciplinary team for intermediate care at home. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2004; 4:e02 [PMC free article: PMC1393274] [PubMed: 16773151]

- 28.

- Bernhaut J, Mackay K. Extended nursing roles in intermediate care: a cost-benefit evaluation. Nursing Times. 2002; 98(21):37–39 [PubMed: 12168441]

- 29.

- Bethell HJ, Mullee MA. A controlled trial of community based coronary rehabilitation. British Heart Journal. 1990; 64(6):370–375 [PMC free article: PMC1224812] [PubMed: 2271343]

- 30.

- Beynon JH, Padiachy D. The past and future of geriatric day hospitals. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2009; 19(1):45–51

- 31.

- Biese K, LaMantia M, Shofer F, McCall B, Roberts E, Stearns SC et al. A randomized trial exploring the effect of a telephone call follow-up on care plan compliance among older adults discharged home from the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014; 21(2):188–195 [PubMed: 24673675]

- 32.

- Blackburn GG, Foody JM, Sprecher DL, Park E, Apperson-Hansen C, Pashkow FJ. Cardiac rehabilitation participation patterns in a large, tertiary care center: evidence for selection bias. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 2000; 20(3):189–195 [PubMed: 10860201]

- 33.

- Blair J, Corrigall H, Angus NJ, Thompson DR, Leslie S. Home versus hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Rural and Remote Health. 2011; 11(2):1532 [PubMed: 21488706]

- 34.

- Board N, Brennan N, Caplan GA. A randomised controlled trial of the costs of hospital as compared with hospital in the home for acute medical patients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2000; 24(3):305–311 [PubMed: 10937409]

- 35.

- Booth JE, Roberts JA, Flather M, Lamping DL, Mister R, Abdalla M et al. A trial of early discharge with homecare compared to conventional hospital care for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Heart. 2004; 90(11):1344–1345 [PMC free article: PMC1768555] [PubMed: 15486143]

- 36.

- Boston NK, Boynton PM, Hood S. An inner city GP unit versus conventional care for elderly patients: prospective comparison of health functioning, use of services and patient satisfaction. Family Practice. 2001; 18(2):141–148 [PubMed: 11264263]

- 37.

- Boter H. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of an outreach nursing support program for recently discharged stroke patients. Stroke. a journal of cerebral circulation 2004; 35(12):2867–2872 [PubMed: 15514186]

- 38.

- Bowler S, Schollay D, Nicholson C, Jackson C, Serisier D, and O’Rourke P. A pilot study comparing substitutable care at home with usual hospital care for acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Brisbane, Australia. Commonwealth department of health and aged care, 2001

- 39.

- Bowman C, Black D. Intermediate not indeterminate care. Hospital Medicine. 1998; 59(11):877–879 [PubMed: 10197122]

- 40.

- Brooks N. Intermediate care rapid assessment support service: an evaluation. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2002; 7(12):623–633 [PubMed: 12514491]

- 41.

- Brooks N, Ashton A, Hainsworth B. Pilot evaluation of an intermediate care scheme. Nursing Standard. 2003; 17(23):33–35 [PubMed: 12655764]

- 42.

- Brunner M, Skeat J, Morris ME. Outcomes of speech-language pathology following stroke: investigation of inpatient rehabilitation and rehabilitation in the home programs. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2008; 10(5):305–313 [PubMed: 20840030]

- 43.

- Bryan K. Policies for reducing delayed discharge from hospital. British Medical Bulletin. 2010; 95(1):33–46 [PubMed: 20647227]

- 44.

- Buus BJ, Refsgaard J, Kanstrup H, Paaske JS, Qvist I, Christensen B et al. Hospital-based versus community-based shared care cardiac rehabilitation after acute coronary syndrome: protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Danish Medical Journal. 2013; 60(9):A4699 [PubMed: 24001464]

- 45.

- Campbell H, Karnon J, Dowie R. Cost analysis of a hospital-at-home initiative using discrete event simulation. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2001; 6(1):14–22 [PubMed: 11219355]

- 46.

- Caplan GA, Coconis J, Woods J. Effect of hospital in the home treatment on physical and cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005; 60(8):1035–1038 [PubMed: 16127109]

- 47.

- Caplan GA, Ward JA, Brennan NJ, Coconis J, Board N, Brown A. Hospital in the home: a randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 1999; 170(4):156–160 [PubMed: 10078179]

- 48.

- Caplan GA, Meller A, Squires B, Chan S, Willett W. Advance care planning and hospital in the nursing home. Age and Ageing. 2006; 35(6):581–585 [PubMed: 16807309]

- 49.

- Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, Aimonino Ricauda N, Wilson AD, Barclay L. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home”. Medical Journal of Australia. 2012; 197(9):512–519 [PubMed: 23121588]

- 50.

- Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department-the DEED II study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(9):1417–1423 [PubMed: 15341540]

- 51.

- Carroll C. Minding the Gap: what does intermediate care do? CME Journal Geriatric Medicine. 2005; 7(2):96–101

- 52.

- Cassel JB, Kerr K, Pantilat S, Smith TJ. Palliative care consultation and hospital length of stay. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010; 13(6):761–767 [PubMed: 20597710]

- 53.

- Chan R, Webster J. A Cochrane review on the effects of end-of-life care pathways: do they improve patient outcomes? Australian Journal of Cancer Nursing. 2011; 12(2):26–30

- 54.

- Chan RJ, Webster J. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013; Issue 11:CD008006. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008006.pub3 [PubMed: 24249255] [CrossRef]

- 55.

- Chappell H, Dickey C. Decreased rehospitalization costs through intermittent nursing visits to nursing home patients. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1993; 23(3):49–52 [PubMed: 8473929]

- 56.

- Chard SE. Community neurorehabilitation: a synthesis of current evidence and future research directions. NeuroRx. 2006; 3(4):525–534 [PMC free article: PMC3593402] [PubMed: 17012066]

- 57.

- Chen A, Bushmeneva K, Zagorski B, Colantonio A, Parsons D, Wodchis WP. Direct cost associated with acquired brain injury in Ontario. BMC Neurology. 2012; 12:76 [PMC free article: PMC3518141] [PubMed: 22901094]

- 58.

- Chumbler NR, Li X, Quigley P, Morey MC, Rose D, Griffiths P et al. A randomized controlled trial on stroke telerehabilitation: the effects on falls self-efficacy and satisfaction with care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2015; 21(3):139–143 [PMC free article: PMC4548802] [PubMed: 25680390]

- 59.

- Coast J, Richards SH, Peters TJ, Gunnell DJ, Darlow MA, Pounsford J. Hospital at home or acute hospital care? A cost minimisation analysis. BMJ. 1998; 316(7147):1802–1806 [PMC free article: PMC28581] [PubMed: 9624074]

- 60.

- Cobelli F, Tavazzi L. Relative role of ambulatory and residential rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk. 1996; 3(2):172–175 [PubMed: 8836859]

- 61.

- Coburn AF, Fortinsky RH, McGuire CA. The impact of Medicaid reimbursement policy on subacute care in hospitals. Medical Care. 1989; 27(1):25–33 [PubMed: 2492065]

- 62.

- Cohen IL, Booth FV. Cost containment and mechanical ventilation in the United States. New Horizons. 1994; 2(3):283–290 [PubMed: 8087585]

- 63.

- Colprim D, Inzitari M. Incidence and risk factors for unplanned transfers to acute general hospitals from an intermediate care and rehabilitation geriatric facility. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014; 15(9):687–4 [PubMed: 25086689]

- 64.

- Colprim D, Martin R, Parer M, Prieto J, Espinosa L, Inzitari M. Direct admission to intermediate care for older adults with reactivated chronic diseases as an alternative to conventional hospitalization. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013; 14(4):300–302 [PubMed: 23294969]

- 65.

- Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(11):1693–1702 [PubMed: 27695822]

- 66.

- Corwin P, Toop L, McGeoch G, Than M, Wynn-Thomas S, Wells JE et al. Randomised controlled trial of intravenous antibiotic treatment for cellulitis at home compared with hospital. BMJ. 2005; 330(7483):129 [PMC free article: PMC544431] [PubMed: 15604157]

- 67.

- Cotton MM, Bucknall CE, Dagg KD, Johnson MK, MacGregor G, Stewart C et al. Early discharge for patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Thorax. 2000; 55(11):902–906 [PMC free article: PMC1745631] [PubMed: 11050257]

- 68.

- Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K, Hamilton K. Fewer emergency readmissions and better quality of life for older adults at risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a 24-week exercise and telephone follow-up program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009; 57(3):395–402 [PubMed: 19245413]

- 69.

- Cowie A, Moseley O. Home- versus hospital-based exercise training in heart failure: an economic analysis. British Journal of Cardiology. 2014; 21(2):76

- 70.

- Craig LE, Wu O, Bernhardt J, Langhorne P. Approaches to economic evaluations of stroke rehabilitation. International Journal of Stroke. 2014; 9(1):88–100 [PubMed: 23521855]

- 71.

- Crawford-Faucher A. Home- and center-based cardiac rehabilitation equally effective. American Family Physician. 2010; 82(8):994–995

- 72.

- Crotty M, Kittel A, Hayball N. Home rehabilitation for older adults with fractured hips: how many will take part? Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice. 2000; 20(2-3):65–68 [PubMed: 11057986]

- 73.

- Crotty M, Miller M, Whitehead C, Krishnan J, Hearn T. Hip fracture treatments-what happens to patients from residential care? Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice. 2000; 20(4):167–170 [PubMed: 11207957]

- 74.

- Crotty M, Whitehead C, Miller M, Gray S. Patient and caregiver outcomes 12 months after home-based therapy for hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003; 84(8):1237–1239 [PubMed: 12917867]

- 75.

- Crotty M, Whitehead CH, Gray S, Finucane PM. Early discharge and home rehabilitation after hip fracture achieves functional improvements: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2002; 16(4):406–413 [PubMed: 12061475]

- 76.

- Cunliffe A, Husbands S, Gladman J. Satisfaction with an early supported discharge service for older people. Age and Ageing. 2002; 31:(Suppl 2):43

- 77.

- Dalal HM, Evans PH. Achieving national service framework standards for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention. BMJ. 2003; 326(7387):481–484 [PMC free article: PMC150183] [PubMed: 12609946]

- 78.

- Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Gunzler D, Lipson AR. Clinical trial of a supportive care team for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013; 46(6):775–784 [PMC free article: PMC3715594] [PubMed: 23523362]

- 79.

- Davies L, Wilkinson M, Bonner S, Calverley PM, Angus RM. “Hospital at home” versus hospital care in patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prospective randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000; 321(7271):1265–1268 [PMC free article: PMC27532] [PubMed: 11082090]

- 80.

- Department of Health. Intermediate care - halfway home. Updated guidance for the NHS and Local Authorities, 2009. Available from: http://webarchive

.nationalarchives .gov.uk/20130107105354/ http:/www .dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh /groups /dh_digitalassets/@dh /@en/@pg/documents /digitalasset/dh_103154.pdf - 81.

- Deutsch A, Granger CV, Heinemann AW, Fiedler RC, DeJong G, Kane RL et al. Poststroke rehabilitation: outcomes and reimbursement of inpatient rehabilitation facilities and subacute rehabilitation programs. Stroke. 2006; 37(6):1477–1482 [PubMed: 16627797]

- 82.

- Dey P, Woodman M, and FASTER trial group. Manchester FASTER trial [unpublished], 2003

- 83.

- Dhalla IA, O’Brien T, Morra D, Thorpe KE, Wong BM, Mehta R et al. Effect of a postdischarge virtual ward on readmission or death for high-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014; 312(13):1305–1312 [PubMed: 25268437]

- 84.

- Dias FD, Sampaio LMM, da Silva GA, Gomes ELFD, do Nascimento ESP, Alves VLS et al. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2013; 8:537–544 [PMC free article: PMC3821544] [PubMed: 24235824]

- 85.

- Dickson HG, Conforti DA. Hospital in the home: a randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 1999; 171(2):109–110 [PubMed: 10474595]

- 86.

- DiMartino LD, Weiner BJ, Mayer DK, Jackson GL, Biddle AK. Do palliative care interventions reduce emergency department visits among patients with cancer at the end of life? A systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014; 17(12):1384–1399 [PubMed: 25115197]

- 87.

- Dolansky MA, Xu F, Zullo M, Shishehbor M, Moore SM, Rimm AA. Post-acute care services received by older adults following a cardiac event: a population-based analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2010; 25(4):342–349 [PMC free article: PMC2885047] [PubMed: 20539168]

- 88.

- Dombi WA. Avalere health study conclusively proves home care is cost effective, saves billions for Medicare yearly, and effectively limits re-hospitalization. Caring. 2009; 28(6):22–23 [PubMed: 19626962]

- 89.

- Donald IP, Baldwin RN, Bannerjee M. Gloucester hospital-at-home: a randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 1995; 24(5):434–439 [PubMed: 8669350]

- 90.

- Donaldson RJ. Hospital versus domiciliary care in acute myocardial infarction. Health and Hygiene. 1982; 4(2-4):103–107

- 91.

- Donath S. Hospital in the home: real cost reductions or merely cost-shifting? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001; 25(2):187–188 [PubMed: 11357920]

- 92.

- Donlevy JA, Pietruch BL. The connection delivery model: care across the continuum. Nursing Management. 1996; 27(5):34–36 [PubMed: 8710342]

- 93.

- Donnelly ML, Jamieson JL, Brett-Maclean P. Primary care geriatrics in British Columbia: a short report. Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Canadian Geriatrics Society. 2002; 5(4):175–178

- 94.

- Dorney-Smith S. Nurse-led homeless intermediate care: an economic evaluation. British Journal of Nursing. 2011; 20(18):1193–1197 [PubMed: 22067642]

- 95.

- Dow B. The shifting cost of care: early discharge for rehabilitation. Australian Health Review. 2004; 28(3):260–265 [PubMed: 15595907]

- 96.

- Dow B, Black K, Bremner F, Fearn M. A comparison of a hospital-based and two home-based rehabilitation programmes. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29(8):635–641 [PubMed: 17453984]

- 97.

- Duffy JR, Hoskins LM, Dudley-Brown S. Improving outcomes for older adults with heart failure: a randomized trial using a theory-guided nursing intervention. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2010; 25(1):56–64 [PubMed: 19512945]

- 98.

- Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, Sloan J, Colon-Otero G. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: results of a randomized pilot study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012; 15(8):890–895 [PMC free article: PMC3396133] [PubMed: 22559906]

- 99.

- Echevarria C, Brewin K, Horobin H, Bryant A, Corbett S, Steer J et al. Early supported discharge/hospital at home for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review and meta-analysis. COPD. 2016; 13(4):523–533 [PubMed: 26854816]

- 100.

- Eldar R. Rehabilitation in the community for patients with stroke: a review. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2000; 6(4):48–59

- 101.

- Elder AT. Can we manage more acutely ill elderly patients in the community? Age and Ageing. 2001; 30(6):441–443 [PubMed: 11742768]

- 102.

- Elliott RA, Thornton J, Webb AK, Dodd M, Tully MP. Comparing costs of home- versus hospital-based treatment of infections in adults in a specialist cystic fibrosis center. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2005; 21(4):506–510 [PubMed: 16262975]

- 103.

- Emme C, Mortensen EL, Rydahl-Hansen S, Ostergaard B, Svarre Jakobsen A, Schou L et al. The impact of virtual admission on self-efficacy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014; 23(21-22):3124–3137 [PubMed: 24476457]

- 104.

- Emme C, Rydahl-Hansen S, Ostergaard B, Schou L, Svarre Jakobsen A, Phanareth K. How virtual admission affects coping - telemedicine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014; 23(9-10):1445–1458 [PubMed: 24372676]

- 105.

- Eron LJ, Marineau M, Baclig E, Yonehara C, King P. The virtual hospital: treating acute infections in the home by telemedicine. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2004; 63(10):291–293 [PubMed: 15570714]

- 106.

- Feltner C, Jones CD, Cene CW, Zheng ZJ, Sueta CA, Coker-Schwimmer EJL et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014; 160(11):774–784 [PubMed: 24862840]

- 107.

- Fenton FR, Tessier L, Struening EL, Smith FA, Benoit C, Contandriopoulos AP et al. A two-year follow-up of a comparative trial of the cost-effectiveness of home and hospital psychiatric treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1984; 29(3):205–211 [PubMed: 6442211]

- 108.

- Franklin BA. Multifactorial cardiac rehabilitation did not reduce mortality or morbidity after acute myocardial infarction. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012; 157(2):JC2–11 [PubMed: 22801702]

- 109.

- Garåsen H, Windspoll R, Johnsen R. Long-term patients’ outcomes after intermediate care at a community hospital for elderly patients: 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2008; 36(2):197–204 [PubMed: 18519285]

- 110.

- Garasen H, Windspoll R, Johnsen R. Intermediate care at a community hospital as an alternative to prolonged general hospital care for elderly patients: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2007; 7:68 [PMC free article: PMC1868721] [PubMed: 17475006]

- 111.

- Gaspoz JM, Lee TH, Weinstein MC, Cook EF, Goldman P, Komaroff AL et al. Cost-effectiveness of a new short-stay unit to “rule out” acute myocardial infarction in low risk patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994; 24(5):1249–1259 [PubMed: 7930247]

- 112.

- Ghanem M, Elaal EA, Mehany M, Tolba K. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation program: effect on exercise tolerance and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 2010; 5(1):18–25 [PMC free article: PMC2841804] [PubMed: 20351956]

- 113.

- Gjelsvik BEB, Hofstad H, Smedal T, Eide GE, Naess H, Skouen JS et al. Balance and walking after three different models of stroke rehabilitation: early supported discharge in a day unit or at home, and traditional treatment (control). BMJ Open. 2014; 4(5):e004358 [PMC free article: PMC4025466] [PubMed: 24833680]

- 114.

- Gladman JR, Lincoln NB. Follow-up of a controlled trial of domiciliary stroke rehabilitation (DOMINO Study). Age and Ageing. 1994; 23(1):9–13 [PubMed: 8010180]

- 115.

- Glasby J, Martin G, Regen E. Older people and the relationship between hospital services and intermediate care: results from a national evaluation. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2008; 22(6):639–649 [PubMed: 19012144]

- 116.

- Glick HA, Polsky D, Willke RJ, Alves WM, Kassell N, Schulman K. Comparison of the use of medical resources and outcomes in the treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage between Canada and the United States. Stroke. 1998; 29(2):351–358 [PubMed: 9472873]

- 117.

- Gobbi M, Monger E, Watkinson G, Spencer A, Weaver M, Lathlean J et al. Virtual Interactive Practice: a strategy to enhance learning and competence in health care students. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2004; 107(Pt 2):874–878 [PubMed: 15360937]

- 118.

- Goossens LMA, Utens CMA, Smeenk FWJM, van Schayck OCP, van Vliet M, van Litsenburg W et al. Cost-effectiveness of early assisted discharge for COPD exacerbations in The Netherlands. Value in Health. 2013; 16(4):517–528 [PubMed: 23796285]

- 119.

- Gracey DR, Viggiano RW, Naessens JM, Hubmayr RD, Silverstein MD, Koenig GE. Outcomes of patients admitted to a chronic ventilator-dependent unit in an acute-care hospital. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1992; 67(2):131–136 [PubMed: 1545576]

- 120.

- Graham LA. Organization of rehabilitation services. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2013; 110:113–120 [PubMed: 23312635]

- 121.

- Grande GE, Farquhar MC, Barclay SI, Todd CJ. Caregiver bereavement outcome: relationship with hospice at home, satisfaction with care, and home death. Journal of Palliative Care. 2004; 20(2):69–77 [PubMed: 15332470]

- 122.

- Graverholt B, Forsetlund L, Jamtvedt G. Reducing hospital admissions from nursing homes: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2014; 14:36 [PMC free article: PMC3906881] [PubMed: 24456561]

- 123.

- Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012; 30(4):394–400 [PubMed: 22203758]

- 124.

- Gregory P, Edwards L, Faurot K, Williams SW, Felix ACG. Patient preferences for stroke rehabilitation. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2010; 17(5):394–400 [PubMed: 21131265]

- 125.

- Gregory PC, Han E. Disparities in postacute stroke rehabilitation disposition to acute inpatient rehabilitation vs. home: findings from the North Carolina Hospital Discharge Database. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2009; 88(2):100–107 [PubMed: 19169175]

- 126.

- Griffiths P. Intermediate care in nursing-led units - a comprehensive overview of the evidence base. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2006; 16(1):71–77

- 127.

- Griffiths P, Harris R, Richardson G, Hallett N, Heard S, Wilson-Barnett J. Substitution of a nursing-led inpatient unit for acute services: randomized controlled trial of outcomes and cost of nursing-led intermediate care. Age and Ageing. 2001; 30(6):483–488 [PubMed: 11742777]

- 128.

- Griffiths P, Wilson-Barnett J. Influences on length of stay in intermediate care: lessons from the nursing-led inpatient unit studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2000; 37(3):245–255 [PubMed: 10754190]

- 129.

- Griffiths P, Wilson-Barnett J, Richardson G, Spilsbury K, Miller F, Harris R. The effectiveness of intermediate care in a nursing-led in-patient unit. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2000; 37(2):153–161 [PubMed: 10684957]

- 130.

- Griffiths P. Effectiveness of intermediate care delivered in nurse-led units. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2006; 11(5):205–208 [PubMed: 16723914]

- 131.

- Griffiths P, Edwards M, Forbes A, Harris R. Post-acute intermediate care in nursing-led units: a systematic review of effectiveness. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005; 42(1):107–116 [PubMed: 15582644]

- 132.

- Gunnell D, Coast J, Richards SH, Peters TJ, Pounsford JC, Darlow MA. How great a burden does early discharge to hospital-at-home impose on carers? A randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 2000; 29(2):137–142 [PubMed: 10791448]

- 133.

- Hackett ML, Vandal AC, Anderson CS, Rubenach SE. Long-term outcome in stroke patients and caregivers following accelerated hospital discharge and home-based rehabilitation. Stroke. a journal of cerebral circulation 2002; 33(2):643–645 [PubMed: 11823686]

- 134.

- Hamlet KS, Hobgood A, Hamar GB, Dobbs AC, Rula EY, Pope JE. Impact of predictive model-directed end-of-life counseling for Medicare beneficiaries. American Journal of Managed Care. 2010; 16(5):379–384 [PubMed: 20469958]

- 135.

- Hannan EL, Racz MJ, Walford G, Ryan TJ, Isom OW, Bennett E et al. Predictors of readmission for complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003; 290(6):773–780 [PubMed: 12915430]

- 136.

- Hansen FR, Spedtsberg K, Schroll M. Geriatric follow-up by home visits after discharge from hospital: a randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing. 1992; 21(6):445–450 [PubMed: 1471584]

- 137.

- Hardy C, Whitwell D, Sarsfield B, Maimaris C. Admission avoidance and early discharge of acute hospital admissions: an accident and emergency based scheme. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2001; 18(6):435–440 [PMC free article: PMC1725709] [PubMed: 11696489]

- 138.

- Harris R, Ashton T, Broad J, Connolly G, Richmond D. The effectiveness, acceptability and costs of a hospital-at-home service compared with acute hospital care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005; 10(3):158–166 [PubMed: 16053592]

- 139.