8. Primary prophylaxis with growth factors (for example granulocyte colony stimulating factor) and/or antibiotics (for example fluoroquinolones). (Topic F1)

Guideline subgroup members for this question

Nicola Perry (lead), Peter Jenkins, Anton Kruger, Barry Hancock and Rosemary Barnes.

Review question

Does prophylactic treatment with growth factors, granulocyte infusion and/or antibiotics improve outcomes in patients receiving anti-cancer treatment?

Rationale

Anticancer treatment, particularly chemotherapy, often incurs the risk of neutropaenia. The depth and duration of neutropaenia are related to the risk of infection, which may be life-threatening. One approach to reducing the risk of life-threatening neutropaenic sepsis is to prevent or moderate the degree of neutropaenia, or to prevent or reduce the likelihood of infection. These strategies may be used independently or concurrently.

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) have been available since the early 1990s to raise neutrophil counts, and shorten the duration of neutropaenia, by stimulating the bone marrow to produce neutrophils. However, side effects include diarrhoea, weakness, a flu-like syndrome, and rarely more serious complications such as clotting disorders and capillary leak syndrome. GCSF and GMCSF must be given by injection, and this may lead to local reactions at the site of administration, and repeated injections may not be desired by patients. Depot formulations are available but expensive.

The likelihood of infection may be reduced by the pre-emptive use of antibiotics, chosen to cover the most likely pathogens, and the time period of greatest risk for infection. The most serious bacterial infections are likely to arise from gram-negative organisms, but as the duration and degree of immunocompromise increase, significant infections can arise from other sources too. Typical antibiotics used for prophylaxis include the fluoroquinolones, and cotrimoxazole. These are given orally, but commonly incur patient-related risks of gut disturbance, allergy, etc and more general risks related to the development of antibiotic resistance in populations.

This research question seeks to establish whether the use of growth factors and/or antibiotics in patients on chemotherapy may reduce the chance of subsequent episodes of neutropaenic sepsis, and improve patient outcomes.

Question in PICO format

Table

GCSF/GMCSF (with or without fluroquinolones or co-trimoxale) Fluoroquinolones alone

METHODS

Information sources and eligibility criteria

The information specialist (SB) searched the following electronic databases: Medline, Premedline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Cinahl, BNI, Psychinfo, Web of Science (SCI & SSCI), ISI proceedings and Biomed Central.

We restricted the search to published trials and systematic reviews of such trials. A Cochrane review of prophylactic antibiotics was published in 2005 (Gafter-Gvili et al, 2005). Our literature search for antibiotic studies was therefore limited to papers published after 2004, to find trials published since Gafter-Gvili et al (2005). Our search for colony stimulating factor trials was not date restricted. The search was done on the 1st of March 2011 and updated on 7th November 2011.

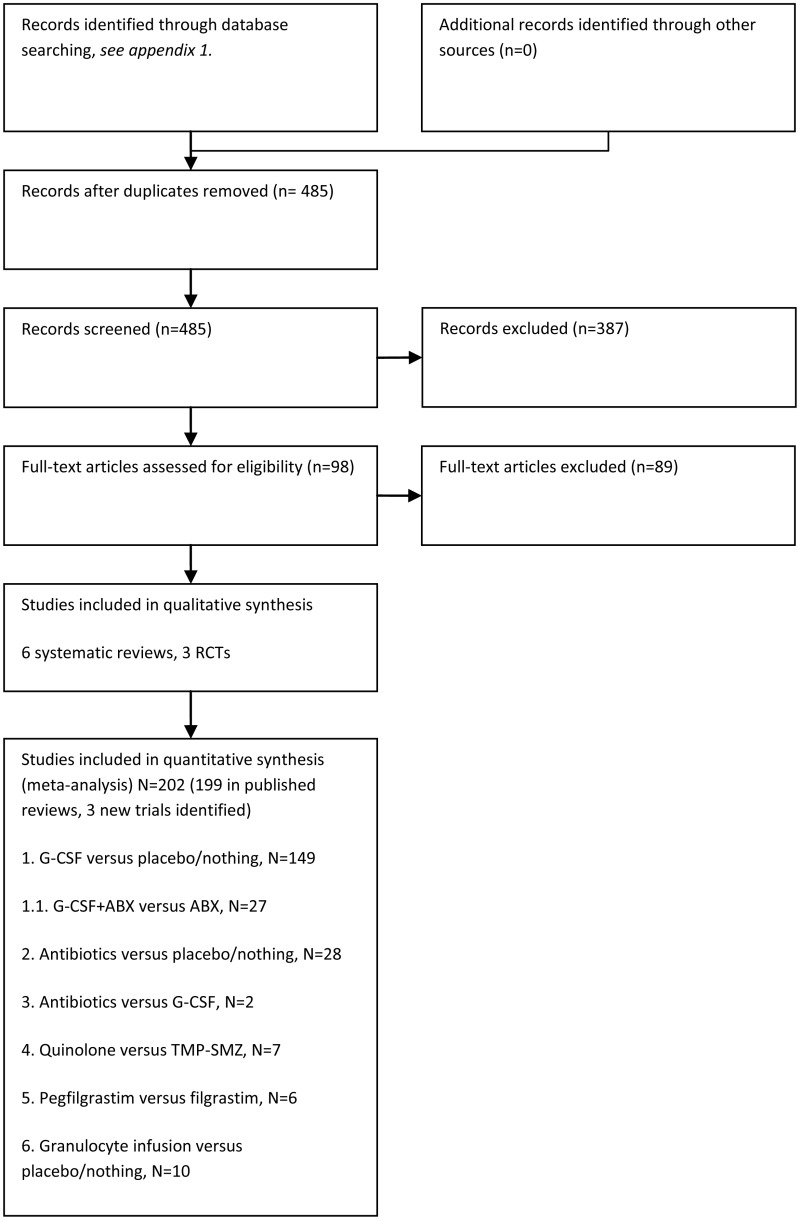

Selection of studies

The information specialist (SB) did the first screen of the literature search results. One reviewer (NB) then selected possibly eligible studies by comparing their title and abstract to the inclusion criteria in the PICO question. The full articles were then obtained for possibly eligible studies and checked against the inclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

The search identified several relevant meta-analyses (Gafter-Gvili et al 2005, 2007; Sung et al 2007; Herbst et al, 2009; Massey et al, 2009 and Pinto, 2007). When the searches identified new data we updated the published meta-analyses if possible. Forest plots were generated whenever additional trials were added to the published meta-analyses, or when new meta-analysis was done.

RESULTS

Comparison 1. G(M)-CSF versus placebo or nothing (with or without antibiotics)

The evidence for primary prophylaxis with colony stimulating factors comes from systematic reviews of randomised trials by Sung, et al., (2007), Bohlius, et al., (2008) and Cooper, et al., (2011). This evidence is summarised in tables 8.1 and 8.2.

Table 8.1

Characteristics of included RCTS.

Table 8.2

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF versus no primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF (with or without antibiotics).

Evidence statements

Mortality

There was high quality evidence from that primary prophylaxis using G(M)-CSF did not reduce short-term all cause mortality when compared to no primary prophylaxis. No reduction in short-term mortality with G(M)-CSF was seen in sub-group analyses (Figure 8.2) according to age group (paediatric, adult or elderly), use of prophylactic antibiotics, colony stimulating factor type (G-CSF or GM-CSF), type of cancer treatment (leukaemia, lymphoma/solid tumour or stem cell transplant).

Figure 8.2

Subgroup analyses of relative risks (and 95% confidence intervals) of short term all cause mortality, infectious mortality and febrile neutropenia, in trials of G(M)-CSF versus placebo or nothing (reported in Sung et al 2007).

Febrile neutropenia

There was moderate quality evidence that prophylaxis using G(M)-CSF reduced the rate of febrile neutropenia when compared to no prophylaxis. The pooled estimate suggested an episode of febrile neutropenia would be prevented for every nine chemotherapy cycles that used G(M)-CSF prophylaxis.

Moderate quality evidence from subgroup analyses suggested that the effectiveness of prophylaxis with colony stimulating factors may vary according to the type of cancer treatment. In the subgroup of leukaemia studies, G(M)-CSF would need to be used for 13 cycles to prevent an additional episode of febrile neutropenia. In solid tumour/lymphoma studies the corresponding number of cycles was nine. In stem cell transplant studies there was serious uncertainty about whether G(M)-CSF helps prevent febrile neutropenia.

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance was not reported in the included systematic reviews (Sung, et al., 2007; Bohlius, et al., 2008 and Cooper, et al., 2011).

Length of hospital stay

There was moderate quality evidence that the use of prophylactic G(M)-CSF was associated with a shorter hospital stay: the mean hospital stay was 2.41 days shorter with G(M)-CSF prophylaxis than without.

Quality of life

Quality of life was not reported in the included systematic reviews (Sung, et al., 2007; Bohlius, et al., 2008 and Cooper, et al., 2011).

Comparison 1.1. G(M)-CSF plus antibiotic (quinolone or co-trimoxazole) versus antibiotic

The trials were identified from the systematic review by Sung, et al., (2007) and from the list of excluded studies in a Cochrane review of prophylactic antibiotics versus G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (Herbst, et al., 2009 ). Most (18/27) of the trials used cotrimoxazole only (specifically for Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis) – these were analysed separately from the nine trials that used quinolones. Three trials that used both quinolones and cotrimoxazole were included in the quinolone group for analysis. The trials were not designed to test the interaction of G(M)-CSF with antibiotics – rather prophylactic antibiotics were part of standard care (many of the these trials also used antiviral and antifungal prophylaxis). This evidence is summarised in Tables 8.3 and 8.5 and Figures 8.3 to 8.8.

Table 8.3

Characteristics of included trials.

Figure 8.3

Relative risk of febrile neutropenia G(M)-CSF + quinolone versus quinolone.

Figure 8.4

Relative risk of all cause mortality G(M)-CSF + quinolone versus quinolone.

Figure 8.5

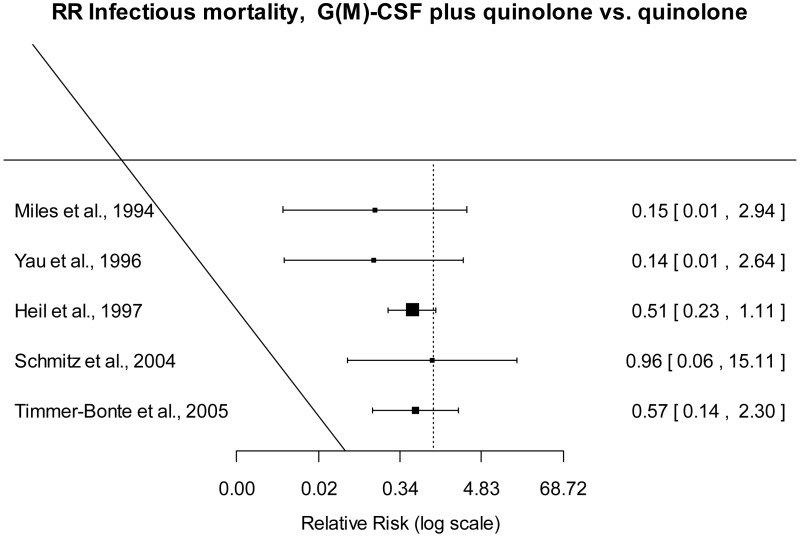

Relative risk of infectious mortality G(M)-CSF + quinolone versus quinolone.

Figure 8.6

Relative risk of febrile neutropenia G(M)-CSF + cotrimoxazole versus cotrimoxazole.

Figure 8.7

Relative risk of all cause mortality G(M)-CSF + cotrimoxazole versus cotrimoxazole.

Figure 8.8

Relative risk of infectious mortality G(M)-CSF + cotrimoxazole versus cotrimoxazole.

Evidence statements

Mortality and Febrile neutropenia

The evidence was of low quality for febrile neutropenia and moderate quality for short term mortality from any cause. There was uncertainty as to whether primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF plus quinolone or quinolone alone was better in terms of these outcomes due to the wide confidence intervals of the pooled estimates.

Infectious mortality

Moderate quality evidence suggested that infectious mortality was lower when G(M)-CSF plus quinolone was used for prophylaxis than with quinolone.

Antibiotic resistance, Length of hospital stay, Quality of life

These outcomes were not reported for this subgroup of studies in Sung, et al., (2007).

Table 8.4

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF plus antibiotics versus primary prophylaxis with antibiotics.

Comparison 2. Antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or co-trimoxazole) versus placebo or nothing

The evidence came from a Cochrane review of antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following anti-cancer treatment by Gafter-Gvili, et al., (2005). Data from trials of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or co-trimoxazole was were extracted from this review and analysed. Evidence about colonisation with resistant bacteria came from a second systematic review by the same authors (Gafter-Gvili, et al., 2007). An additional trial (Rahman and Khan, 2009) of levofloxacin prophylaxis was indentified in our literature search. The evidence is summarised in Tables 8.5 and 8.6 and in Figures 8.9 to 8.12.

Table 8.5

Characteristics of included trials.

Table 8.6

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with antibiotics versus no primary prophylaxis.

Figure 8.9

Antibiotic versus placebo, mortality.

Figure 8.10

Antibiotic versus placebo, febrile neutropenia.

Figure 8.11

Antibiotic versus placebo, infection with bacteria resistant to the antibiotic used for prophylaxis.

Figure 8.12

Antibiotic versus placebo, colonisation of bacteria resistant to the antibiotic used for prophylaxis.

Evidence statements

Mortality

There was moderate quality evidence that prophylactic quinolones (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin) reduced short-term all cause mortality when compared with no prophylaxis. From the pooled estimate, 59 patients would need prophylactic quinolones to prevent one additional death.

No ofloxacin studies reported the rates of all cause mortality.

Febrile neutropenia

The review analysed the rates of febrile neutropenia by patient (rather than by cycle). When patient rates were not reported, febrile episodes were used for the numerator. There was moderate quality evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis reduced the rate of febrile neutropenia, however there was inconsistency between individual study's estimates of effectiveness.

Subgroup analysis according to antibiotic suggested that levofloxacin, ofloxacin and cotrimoxazole might be more effective than ciprofloxacin in preventing febrile neutropenia.

However, even after grouping studies according to antibiotic used, there was still heterogeneity within the ofloxacin and cotrimoxazole groups.

The highest quality evidence came from the three levofloxacin trials. The pooled estimate from these trials suggested that 11 patients would need antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent one additional episode of febrile neutropenia.

Antibiotic resistance

There was moderate quality evidence that infection with bacteria resistant to the antibiotic used for prophylaxis was more likely in patients receiving antibiotic prophylaxis. The pooled estimate suggested an additional resistant infection for every 77 patients who received antibiotic prophylaxis.

There was very low quality evidence about the rates of colonisation with resistant bacteria.

Two trials reported only 8 cases of colonisation with resistant bacteria, in 143 patients. It is impossible to get an accurate estimate of the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis on resistant colonisation with such a low number of events.

None of the trials reported the rates of colonisation with resistant bacteria before antibiotic prophylaxis or how these related to rates following prophylaxis.

Length of hospital stay

Although the Gafter-Gvili, et al., (2005) review considered this outcome, data on the length of hospital stay were too sparse to allow analysis

Quality of life

Quality of life was not considered as an outcome in the systematic review.

Comparison 3. Quinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin or ofloxacin) versus co-trimoxazole

Evidence came from a Cochrane review of antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following anti-cancer treatment by Gafter-Gvili, et al., (2005). Evidence about colonisation with resistant bacteria came from a second systematic review by the same authors (Gafter-Gvili, et al., 2007). The evidence is summarised in Tables 8.7 and 8.8. Data from trials of comparing ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxcain to co-trimoxazole was extracted and analysed (see Figures 8.13 to 8.16).

Table 8.7

Characteristics of included trials.

Table 8.8

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with quinolone versus cotrimoxazole.

Figure 8.13

Quinolone versus cotrimoxazole, mortality.

Figure 8.14

Quinolone versus cotrimoxazole, febrile neutropenia.

Figure 8.15

Infection with bacteria resistant to antibiotic used for prophylaxis.

Figure 8.16

Colonisation with bacteria resistant to antibiotic used for prophylaxis.

Evidence statements

Mortality

There was uncertainty as to whether prophylaxis with quinolones or cotrimoxazole was better in terms of short-term mortality. The 95% confidence intervals of the pooled estimate were were wide enough to include the possibility that either antibiotic was significantly better than the other.

Febrile neutropenia

There was low quality evidence to suggest that prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia was more effective with ofloxacin than with cotrimoxazole. There was uncertainty about whether ciprofloxacin was more effective than cotrimoxazole, and there were no studies comparing levofloxacin with cotrimoxazole.

Antibiotic resistance

Low quality evidence suggested both infection and colonisation with bacteria resistant to the antibiotic used for prophylaxis was more likely with cotrimoxazole than with a quinolone.

Length of hospital stay and Quality of life

Data on length of stay were sparse and not analysed. Quality of life was not reported

Comparison 4. G(M)-CSF versus antibiotics

Evidence came from a Cochrane review of prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (Herbst, et al., 2009). This review included two randomised trials directly comparing G(M)-CSF with antibiotics, remarkably few given the large number of trials comparing primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF or antibiotics to no primary prophylaxis. Schroeder. et al., (1999) compared G-CSF to ciprofloxacin plus amphotericin B. Sculier, et al., (2001) compared GM-CSF to cotrimoxazole. The evidence is summarised in Tables 8.9 and 8.10.

Table 8.9

Characteristics of included trials.

Table 8.10

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF versus antibiotic.

Evidence statements

Mortality

One trial reported short term mortality. Due to the very low number of events there was serious uncertainty and it is not possible to conclude that the treatments are equivalent or that one is superior to the other

Febrile neutropenia

One trial reported febrile neutropenia. Due to the very low number of events there was serious uncertainty and it is not possible to conclude that the treatments are equivalent or that one is superior to the other

Antibiotic resistance

This outcome was not considered in the systematic review.

Length of hospital stay

One trial reported the median length of hospital stay was 6 days with G-CSF compared with 7 days with antibiotic prophylaxis. This difference was not statistically significant.

Quality of life

Neither of the trials reported this outcome

Comparison 5. Pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim

Evidence came from systematic review and meta-analysis of prophylactic G-CSFs which included a comparison of pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim for the prevention of neutropenia in adult cancer patients with solid tumours or lymphoma undergoing chemotherapy (Cooper, et al., 2011). This review included five randomised trials. The literature search identified an additional phase II randomised trial comparing pegfilgrastim to filgrastim for prophylaxis in children with sarcoma receiving chemotherapy (Spunt, et al., 2010). The evidence is summarised in Tables 8.11 and 8.12 and in Figure 8.17.

Table 8.11

Characteristics of included trials.

Table 8.12

GRADE evidence profile for primary prophylaxis with pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim.

Figure 8.17

Pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim, febrile neutropenia.

Evidence statements

Short term mortality

Short term mortality was not considered in Cooper, et al., (2011). One trial included in the systematic review reported mortality, but there was only one death (in the filgrastim group). Spunt, et al., (2010) did not report mortality.

Febrile neutropenia

Low quality evidence from five randomised trials (Cooper, et al., 2011) suggested pegfilgrastim was more effective than filgrastim in the prevention of febrile neutropenia, RR = 0.66 (95% C.I. 0.44 to 0.98).

Antibiotic resistance, Length of hospital stay and Quality of life

These outcomes were not considered in the systematic review.

Comparison 6. Granulocyte infusion versus placebo or nothing

Evidence came from a Cochrane review of granulocyte transfusions for preventing infections in patients with neutropenia or neutrophil dysfunction (Massey, et al., 2009). This review included ten trials, all but one of which were carried out before 1988. The evidence is summarised in Tables 8.13 and 8.14.

Table 8.13

Characteristics of included trials.

Table 8.14

GRADE evidence profile for prophylaxis with granulocyte infusion versus no such prophylaxis.

Evidence statements

Mortality

Due to the relatively low number of events, there was uncertainty as to whether prophylactic granulocyte infusions reduce short-term all cause mortality in this population.

Febrile neutropenia

Due to the relatively low number of events, there was uncertainty as to whether prophylactic granulocyte infusions reduce the rate of febrile neutropenia in this population.

Antibiotic resistance

This outcome was not considered in the systematic review.

Length of hospital stay

Massey, et al., (2009) found little consistency in the reporting of duration of treatment and length of hospital stay, and chose not analyse this outcome further.

Quality of life

No trials reported this outcome

REFERENCES

- Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Paul M, van de Wetering M, Kremer L, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following chemotherapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(4) [Review] [190 refs] CD004386, 2005., CD004386. [PubMed: 16235360]

- Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Fraser A, Leibovici L. Effect of quinolone prophylaxis in afebrile neutropenic patients on microbial resistance: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2007;59:5–22. [PubMed: 17077101]

- Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB, Monsef I, Bohlius J, Schulz H, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1) [Review] [91 refs] CD007107, 2009., CD007107. [PubMed: 19160320]

- Massey E, Paulus U, Doree C, Stanworth S. Granulocyte transfusions for preventing infections in patients with neutropenia or neutrophil dysfunction. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1) [Review] [51 refs] CD005341, 2009., CD005341. [PubMed: 19160254]

- Pinto L, Liu Z, Doan Q, Bernal M, Dubois R, Lyman G. Comparison of pegfilgrastim with filgrastim on febrile neutropenia, grade IV neutropenia and bone pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2007;23:2283–2295. [PubMed: 17697451]

- Rahman MM, Khan MA. Levofloxacin prophylaxis to prevent bacterial infection in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in acute leukemia. Bangladesh Medical Research Council Bulletin. 2009;35:91–94. [PubMed: 20922911]

- Spunt SL, Irving H, Frost J, Sender L, Guo M, Yang BB, et al. Phase II, randomized, open-label study of pegfilgrastim-supported VDC/IE chemotherapy in pediatric sarcoma patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1329–1336. [PMC free article: PMC2834494] [PubMed: 20142595]

- Sung L, Nathan PC, Alibhai SM, Tomlinson GA, Beyene J. Meta-analysis: effect of prophylactic hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors on mortality and outcomes of infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147:400–411. [PubMed: 17876022]

EVIDENCE TABLES

Download PDF (255K)

9. Secondary prophylaxis with growth factors, granulocyte infusion and/or antibiotics. (Topic F2)

Guideline subgroup members for this question

Nicola Perry (lead), Peter Jenkins, Anton Kruger, Barry Hancock and Rosemary Barnes.

Review question

Does prophylactic treatment with growth factors, granulocyte infusion and/or antibiotics improve outcomes in patients with a prior episode of neutropenic sepsis?

Rationale

Anticancer treatment, particularly chemotherapy, often incurs the risk of neutropaenia. The depth and duration of neutropaenia are related to the risk of infection, which may be life-threatening. One approach to reducing the risk of life-threatening neutropaenic sepsis is to prevent or moderate the degree of neutropaenia, or to prevent or reduce the likelihood of infection. These strategies may be used independently or concurrently.

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) have been available since the early 1990s to raise neutrophil counts, and shorten the duration of neutropaenia, by stimulating the bone marrow to produce neutrophils. However, side effects include diarrhoea, weakness, a flu-like syndrome, and rarely more serious complications such as clotting disorders and capillary leak syndrome. GCSF and GMCSF must be given by injection, and this may lead to local reactions at the site of administration, and repeated injections may not be desired by patients. Depot formulations are available but expensive.

The likelihood of infection may be reduced by the pre-emptive use of antibiotics, chosen to cover the most likely pathogens, and the time period of greatest risk for infection. The most serious bacterial infections are likely to arise from gram-negative organisms, but as the duration and degree of immunocompromise increase, significant infections can arise from other sources too. Typical antibiotics used for prophylaxis include the fluoroquinolones, and cotrimoxazole. These are given orally, but commonly incur patient-related risks of gut disturbance, allergy, etc and more general risks related to the development of antibiotic resistance in populations.

This research question seeks to establish whether the use of growth factors and/or antibiotics in patients on chemotherapy who have previously experienced neutropaenic sepsis, may reduce the chance of subsequent severe episodes of neutropaenic sepsis, and improve patient outcomes.

Question in PICO format

Table

G(M)-CSF (with or without fluoroquinolones), Fluoroquinolones alone

METHODS

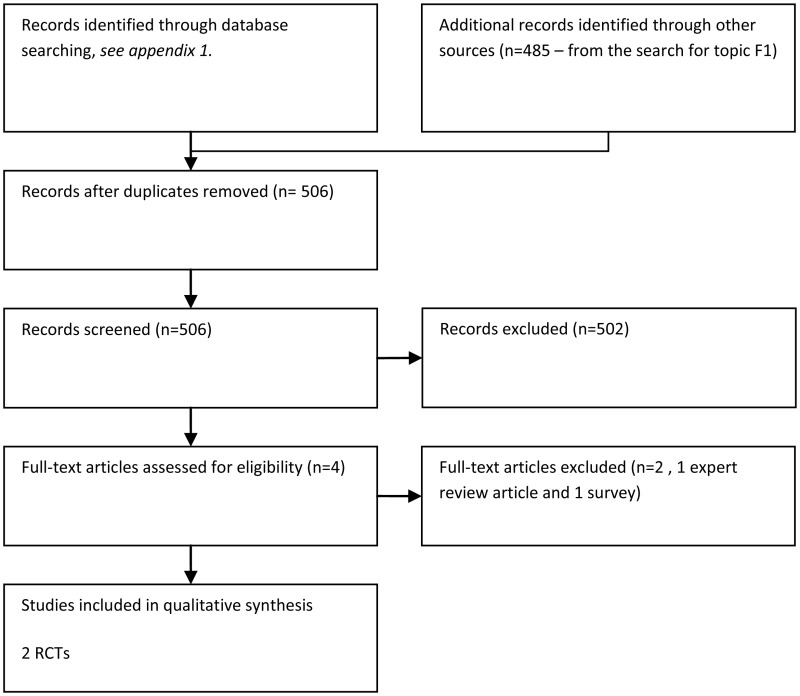

Information sources

The information specialist (SB) searched the following electronic databases: Medline, Premedline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Cinahl, BNI, Psychinfo, Web of Science (SCI & SSCI), ISI proceedings and Biomed Central. The full strategy will be available in the full guideline. The search was done on 14th March 2011, and updated on 7th of November 2011.

We also screened the results of the search for topic F1 (primary prophylaxis with G-CSF or antibiotics) for any secondary prophylaxis studies. Trials comparing primary with secondary prophylaxis were excluded.

Selection of studies

The information specialist (SB) did the first screen of the literature search results. One reviewer (NB) then selected possibly eligible studies by comparing their title and abstract to the inclusion criteria in the PICO question. The full articles were then obtained for possibly eligible studies and checked against the inclusion criteria.

RESULTS

Comparison 1. G(M)-CSF versus placebo or nothing (with or without antibiotics)

The literature search identified one randomised trial (Leonard, et al., 2009) published in abstract form only. This trial compared secondary prophylaxis using G-CSF with standard management (dose delay or reduction) in patients with early stage breast cancer receiving anthracyline or anthracycline-taxane sequential regimes. The evidence is summarised in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1

GRADE evidence profile. For secondary prophylaxis with G(M)-CSF versus no secondary prophylaxis

Evidence statements

Incidence of neutropenic sepsis

The rate of neutropenic sepsis was not reported. The trial reported the rate of neutropenic events, indirectly related to neutropenic sepsis and for this reason the evidence was considered low quality. The evidence suggested approximately two patients would need secondary prophylaxis with G-CSF to prevent one additional neutropenic event.

Overtreatment, death, critical care, length of stay, duration of fever, quality of life

These outcomes were not reported

Comparison 2. Antibiotics versus placebo or nothing (with or without G(M)-CSF)

No trials of antibiotics for secondary prophylaxis were identified. One low quality randomised trial compared G-CSF plus ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin to G-CSF alone for secondary prophylaxis (Maiche and Muhonen, 1993). The evidence is summarized in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2

GRADE evidence profile. For secondary prophylaxis with quinolone plus G-CSF versus G-CSF alone

In six trials comparing ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin or co-trimoxazole prophylaxis with placebo or nothing (Gafter-Gvili et al, 2005), prophylactic antibiotics were started only in neutropenic patients. However patients were randomised before they experienced neutropenia or fever, so they were not included in this review.

Evidence statements

Incidence of neutropenic sepsis

The rate of neutropenic sepsis was not reported, but Maiche and Muhonen (1993) reported the rate of documented infections. There was uncertainty as to whether prophylaxis with antibiotics plus G-CSF was more effective than G-CSF alone in preventing documented infection, due to the low number of documented infections and small size of the study.

Overtreatment, death, critical care, length of stay, duration of fever, quality of life

These outcomes were not reported

Comparison 3. G-CSF versus antibiotics

No trials were identified.

REFERENCES

- Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Paul M, van de Wetering M, Kremer L, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following chemotherapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(4) [Review] [190 refs] CD004386, 2005., CD004386. [PubMed: 16235360]

- Leonard RCF, Mansi J, Benstead K, Stewart G, Yellowlees A, Adamson D, et al. Secondary PROphylaxis with G-CSF has a major effect on delivered dose intensity: The results of the UK NCRI/anglo celtic SPROG trial for adjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;271 Supplement, Conference.

- Maiche AG, Muhonen T. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) with or without a quinolone in the prevention of infection in cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer. 1993;29A:1403–1405. [PubMed: 7691114]

EVIDENCE TABLES

Download PDF (226K)

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), London

NLM Citation

National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK). Neutropenic Sepsis: Prevention and Management of Neutropenic Sepsis in Cancer Patients. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); 2012 Sep. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 151.) Preventative Treatment: guideline chapter five.