Digital technologies can contribute to strengthening health systems functions and improving health system performance (OECD, 2019). They not only are an integral part of the building block “medical products, vaccines and technologies” (WHO, 2007) of health systems, but can and have reshaped health systems to better achieve their intermediate and final goals and make progress on UHC and the SDGs.

Digital tools can support the (remote and/or safe) delivery of services for marginalized and vulnerable groups, thereby also improving access and equity of the health system. They can enhance coordination of care, aid in provider decision-making, and help monitor care delivery processes to improve care quality and safety. They are also deployed to support management aspects to streamline the administrative burden among health professionals. All this impacts health system efficiency and healthcare costs to patients and providers. Digital applications may also ease payment procedures to expand coverage and reduce financial risk, and have contributed to transforming the delivery of health promotion, patient-provider communication, and patient autonomy and self-management. Digitalization of health system-related data also facilitates the generation of data-driven insights to improve patient outcomes and health system performance, for the benefit of patients, providers, and other stakeholders (Tran et al., 2022; Panteli et al., 2023). It can also drive innovation and economic growth, while protecting public health from future emergencies and enabling precision responses in times of crisis (OECD, 2023a).

However, a health system’s ability to harness the full potential of digital technologies is dependent on myriad factors, within and outside the system. These include general broadband (internet) coverage, digital infrastructure, data governance frameworks, investment, and the health system’s capacity to adapt and deploy such tools and mechanisms (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). Digital transformation in the health sector is not a simple matter of technical change but requires adaptive change in human attitudes and skills, as well as adjustments to legal frameworks and the organization of work (Socha-Dietrich, 2021; OECD, 2023b). Further, health data are essential to modern healthcare delivery, health system management, and research and innovation, and must be well governed to foster their use while protecting privacy and data security (OECD, 2022; Panteli et al., 2023). For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, countries with wide internet connectivity, adequate funding, more developed digital infrastructure, and robust privacy and data governance frameworks were better able to develop, introduce, and implement and adopt digital technologies, and utilize the data generated to gain insights to further advance treatment and pandemic response (Fahy et al., 2021; Panteli et al., 2023).

Demonstrating how much digital health relies on factors distally related to the health system, a 2015 survey from the WHO Regional Office for Europe found that the four main barriers to digital solutions’ implementation are 1) lack of funding, 2) competing health systems priorities, 3) lack of legal regulations or legislation on telehealth programmes, and 4) lack of equipment or connectivity for a suitable infrastructure (WHO, 2016 and WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). There is, however, a difference between digital implementation and effective digital adoption. Investing in digital technologies without a strong data and digital foundation – such as introducing policies that govern the interoperability and integration of tools, education programmes to introduce digital tools and incentivize their use, or measurements for how data are improving care and research – results in wasteful investments and failure to achieve the desired objectives of digitalization of the health system. This is because a technology-first approach incentivizes the production and introduction of unconnected widgets and tools, rather than a holistic data and digital approach that prioritizes interoperable and integrated digital solutions that generate, process, and use data to drive individual treatment and evidence-based policy.

The trajectory for the adoption of digital tools for the desired outcomes is long and multidimensional. According to the clinical adoption meta-model (CAMM), it entails four interdependent and time-dependent dimensions after deployment: availability, use, clinical behaviour, and clinical outcomes (Price & Lau, 2014). More indicators are now being developed to monitor the progress of digitalization of health in countries; however, these are derived from a diversity of sources with different methodologies and nomenclatures, and there is not one standard set of consensus-based, international indicators that can provide policy-makers with a comprehensive and balanced view of the situation in their health systems.

Indicators often focus on the status of the foundations within a country that are necessary for the introduction of digital health initiatives (i.e., the availability stage) and perhaps their utilization (i.e., the use stage) but not their overall adoption. Digital health initiatives need to be part of the wider health needs and digital health ecosystem, characterized by robust governance structures, laws, policies and national strategies that support and guide integration of leadership, financial, organizational, human and technological resources, to implement digital health initiatives, the digital health enabling environment. Qualitative and quantitative indicators reflecting these factors are also being considered in different settings (GDHM, 2023). Additionally, indicators to capture and assess the status of implementation and adoption of essential digital health tools, such as electronic health records (EHR), telehealth programmes, mHealth services, and big data and advanced analytics for health, are also crucial for monitoring the progress of digitalization in a health system, but available data sources are limited.

Because of these limitations, and the cross-cutting placement of digital health in the HSPA frameworks, this section outlines only a selection of core indicators that can be used as tracers to signpost areas where action might be needed to advance the adoption of digital health, or where a closer look would uncover opportunities for policy action. The selected indicators focus specifically on the delivery of healthcare rather than digitalization as a whole (i.e., they do not capture the secondary use of data). They were chosen based on their meaningfulness for driving equitable access to digital health (see WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022a) and their feasibility given current data options, no matter a country’s stage in the digitalization journey, taking into consideration that the WHO European Region encompasses 53 countries with varying degrees of HIS development. Ultimately, it is essential to have indicators capturing the status of all four stages of adoption to meaningfully evaluate the progress of digitalization towards achieving desired goals. However, the initial selection of indicators in this section corresponds to the first two dimensions on availability and system use, and measure the fundamentals within these dimensions. No matter where a country is on its health digitalization journey, these indicators are first horizons to explore towards ensuring sustainable digitalization efforts in health, either by confirming that appropriate resources are in place for adoption and to achieve outcome benefits or to flag where intervention at an early stage is necessary. At the end of the section, we reflect on what future directions for key indicators should strive to capture towards a more fulsome understanding of digital health ecosystems and how they vary across countries.

The selected indicators in this section are grouped according to the following key policy questions related to digital health:

- Are there digital health governance standards in place to ensure digitalization efforts are aligned and outcome-oriented?

- Does the health sector have the right Information and Communication Technologies available?

- Is the health system leveraging digital tools to deliver health services?

- Are staff and users well prepared to use digital health services?

3.1. Policy question: Are there digital health governance standards in place to ensure digitalization efforts are aligned and outcome-oriented?

Despite the promise of digital health services, not all health systems make the same use of their potential (OECD, 2022; Panteli et al., 2023). Digital health services, like clinical services, are usually not evenly distributed among the population, leading to inequalities. One possible reason for this is the fragmentation of the landscape of digital health applications, as a result of weaknesses in the enabling environment (for example, related to leadership or governance and funding insufficiencies). Robust governance mechanisms, such as established digital leadership, a national digital health strategy integrating leadership, financial, organizational, human and technological resources and objectives, as well as health data governance frameworks, are crucial for driving the digital transformation of health (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). The WHO global strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025 posits that a country’s digital health strategy should be designed to advance the level and quality of a country’s digitalization and achieve positive health outcomes, and be aligned with national health plans to promote a country’s highest health policy priorities and efforts towards UHC (WHO, 2021). It is thus first important to monitor whether countries have a national (or nationally harmonized) digital health strategy, a digital health policy, or the equivalent (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023) that provides standards for how digital solutions are to be rolled out to ensure coherence, connectedness, and interoperability. Given the importance of health data in digital health ecosystems, it is important that digital and data strategies for health are aligned – ideally with integrated governance, metrics, and funding.

Accordingly, the indicator providing a starting point for assessing digital health governance standards is:

- National (or nationally harmonized) digital health governance

National (or nationally harmonized) digital health governance

In practice, this indicator means the existence (in clear, traceable form) of a governance document on digital health with explicit, strategic goals and responsibilities. This can be a significant driver for the successful (or unsuccessful) deployment, implementation, and adoption of digital health and can impact different health system functions and objectives – from the proximal end of the HSPA pathway towards achievement of goals at the distal end (see Fig. 3.1). Health data governance may explicitly be a part of such a document or separate from it, but it must be strongly integrated as data governance is a pre-condition for interoperability and connectability of solutions. An effective strategy for both digital health and data in health are essential to achieve outcomes and fulfil the promises of digitalization within the context of a country.

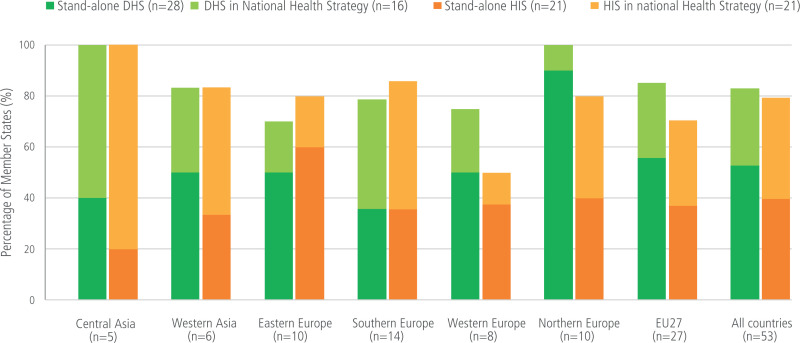

The WHO Global Observatory for eHealth and the WHO Regional Office for Europe both have monitored the existence of strategies and policies for digital health across countries (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). The results of the 2022 survey on digital health in the WHO European Region found that 83% of Member States (44 of 53) have a digital health strategy (see Fig. 3.1). Of these 44, 28 are stand-alone and 16 are addressed within a national health strategy or policy, or a broader digital strategy. The central Asian and northern European regions show the highest rates of having a national DHS or policy; all but one country in Northern Europe had a stand-alone national strategy. Other possible sources for this indicator include the European Health Information Gateway or national, publicly available sources. This variability is mirrored in work carried out by the OECD, both in terms of overall strategies and specific provisions for data governance (Oderkirk, 2021; De Biennassis et al., 2022).

Figure 3.1

European Region Member States with digital health policies or strategies, 2022. Source: WHO (2023)

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

The key limitation in interpreting this indicator if it is collected in a binary response format is that it does not capture the quality or content scope of these documents. It does not cover, for example, integration into the wider digital health ecosystem or enabling environment, or whether data governance is included and to what degree. Further, this indicator does not monitor the extent to which these strategic documents have been implemented. What is more, the content of an effective digital health strategy is generally debated (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023); the WHO Regional Office for Europe has acknowledged the importance of providing technical support to its Member States in the development of their strategies (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022b).

How does this indicator help monitor and transform digital health governance?

The existence of a strategy for the delivery of digital health services can be considered a proxy for an environment conducive to the introduction of specific measures aimed at enabling the delivery of digital health services, such as the revision of scope of practice of the health professions or payment mechanisms for providers. If policy-makers identify that their health systems are outliers in the regional or subregional context, they can be moved to action and can have insights on potential collaborators for cross-country learning. Stakeholder engagement in the development of such strategies is crucial to ensure that direction and timeframes are realistic and fit for purpose, and that avenues for the participation of patients and providers in the development of individual health tools are embedded to ensure these tools can work to their advantage and are consequently likely to be meaningfully implemented.

3.2. Policy question: Does the health sector have the right Information and Communication Technologies available?

Information and communication technologies (ICT) are a set of technological tools and resources used to generate, store, manage, and share information (UNESCO, 2023). Health ICT, more specifically, is anchored in the development and use of digital technologies, databases, and other applications to prevent, treat, and manage illness, while also providing capacity to the system. The use of ICT in health by providers and patients has expanded rapidly in recent years; it has become essential to improving medical care, including by encouraging patient participation and empowerment and preventing medical mistakes, and providing services. Additionally, a country’s ICT environment – what infrastructure exists and what mechanisms are in place for executing digital health interventions, including hardware and digital applications – contributes to a health system’s ability to profit from digital health technologies, along with a country’s digital enabling environment (WHO, 2021). Underpinning effective deployment and adoption of ICT are two critical aspects: 1) the integration and placement of the right mix of ICT technologies into the larger digital health architecture in line with population health needs; and 2) having the right policies in place that enable timely access to quality data generated by ICT in addition to the technologies themselves (see also the previous policy question). The WHO and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), recognizing the importance of ICT, have published recommendations and strategic guidelines for the adoption of ICT in the health sector (PAHO/Nic.br, 2018). Among other elements, these recognize that ICT adoption for the successful delivery of health services fundamentally requires reliable internet access and equipment that is fit for purpose and interoperable. The two indicators chosen to provide a starting point for assessing the availability of the right ICT basic infrastructure in the health sector focus on health service providers as an entry point for the assessment of the availability of these two elements across a country’s territory. They include:

- Health facilities with internet access

- Health facilities with ICT equipment

Health facilities with internet access

Access to and management of information, services, and support in the health system via online portals and internet-connected tools and hardware are a prerequisite for advancing the implementation of digital health. Therefore, adequate internet access in health facilities is fundamental.

Improvements in broadband (internet) connectivity and ICT infrastructure were the most cited measure by a majority of countries in a 2022 survey in the WHO European Region for ensuring equity in access to digital healthcare services (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). However, internet access is often unequally distributed within and across countries, leading to digital exclusion (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023), which contributes to inequality and poor health outcomes. The term is applied more often to individuals – where those in most need (who historically encounter greater care access challenges), such as marginalized groups, those with disabilities, older people, and those living in remote regions, are often those less likely to have access to digital platforms (Park, 2022) – but could be applied in the context of health facilities. In this sense, those facilities without internet access are more likely to face insufficiencies and inequities in terms of funding, staffing, and connectivity otherwise, for example, geographic remoteness. Digital exclusion in this sense impacts on access, quality, coordination, and integration of care, exacerbating existing challenges and inequalities, and contributes to inefficiencies both in individual facilities and the system as a whole. It is therefore important to be able to assess and monitor access to the internet at the subnational level.

The indicator “health facilities with internet access” is defined as the percentage of health facilities by type and region/geography, with internet access. Here, internet access is considered access via a connection owned or paid for by an institution or company. Internet access via devices belonging to (or paid for by) employees is not taken into account. Health facilities are categorized into different types depending on the level of care in which they operate, such as primary care, outpatient specialist care or hospital care, as well as type of ownership (public or private) and management, and size.

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

Data on the number of facilities with internet access do not capture the quality, stability, or speed of internet available. What is more, unless the indicator is collected and evaluated disaggregated for different regions within a country, crucial disparities would be masked. Given these complexities, an additional, complementary indicator would relate to the percentage of territory that has sufficient mobile or fixed broadband connectivity (and distribution of network). A joint consideration (share of health facilities with internet access by territorial unit with different levels of broadband coverage) would allow for a more nuanced understanding of the progress of digitalization in healthcare.

Information for this first indicator – percentage of health facilities (by type) with internet access (by region or another subnational geographic categorization) – is currently not readily available. It is gathered by labour- and time-intensive surveys conducted at regional, country, and transnational levels, on an irregular basis (see, for example, CETIC.br/Nic.br, 2021) and not available in a central repository. Similarly, data collection on the quality of internet connections is conducted sporadically and via surveys. One for the European region assessed how fast internet connections were in hospitals: with over half (56%) of hospitals having a broadband connection below 50 Mbps, and only 16% having a fast connection above 100 Mbps, hospitals were found not to be well equipped in terms of internet connections (Sabes-Figuera & Mahrios, 2013). Further, contextual issues related to target and reference populations of the survey, and definitions of units of analysis, i.e., how health facilities are defined and inclusion criteria, may make comparability difficult (PAHO/Nic.br, 2018). More generally, the OECD notes that more than 60% of the public use the internet to access public authorities, demonstrating that internet usage is increasing; however, there is still significant progress to be made (OECD, 2023b, 2023c).

Health facilities with ICT equipment

Internet connectivity is a pre-condition for the use of ICT in health facilities but does not provide information on the actual use of ICT solutions in the health system. ICT in health is not accessible in all countries or communities equally, leading to further digital exclusion, contributing to inequalities in access to and quality of care, and inefficiencies in the system. Despite the proliferation of government digital health agendas, there is a lack of internationally comparable, reliable, systematic, and regularly updated data to track the uptake and use of ICT in the health sector (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). A dearth of ICT equipment in health facilities can be due to poor planning, management, budgeting, or other systemic reasons. Exploring the degree to which ICT equipment is available across health facilities is the first step to capturing ICT use and adoption by healthcare professionals. The relevant indicator is defined as the number of health facilities (by type) with ICT equipment (by type) according to region/geography divided by the total number of health facilities by type and region/geography, and helps to understand where and how appropriate action can be taken.

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

While there is value in assessing the infrastructure and ICT environments available in the health sector to be able to appropriately plan for the adoption of different interventions across settings, this indicator does not capture the quality and functionality of available ICT equipment, or its actual use. However, identifying if health facilities even have the necessary equipment to begin with is a first step towards understanding what needs must be covered to ensure minimum standards across the territory. As with the previous indicator, geographic breakdown of this indicator would be crucial for a sufficiently granular picture. Meanwhile, it is recognized that while ICT adoption at any level (facility, local, regional, national) requires easily accessible health information and internet access, a coherent systemic adoption of digital health requires that ICT equipment fits into an ideally interoperable digital health ecosystem, which may include data linkage possibilities and assured, safe data access across facilities and platforms; otherwise digitalization can increase the burden on providers instead of alleviating it. Second-level indicators could also include looking at how the ICT available at facility level fits in with given population health needs and within the context of the overall architecture to ascertain whether facilities have the right combination of ICT, or whether the data collected are linked by digital identifier across facilities. This will also consider the integration of ICT into clinical process flows related to the CAMM noted above, along with ensuring sufficient resources to support the effective use of ICT while improving patient outcomes and provider experience measures.

Here, too, key limitations for this indicator include an existing lack of data and the temporal and financial challenges of utilizing surveys. These, as above, also come with contextual challenges, for example, around defining the unit of analysis, facility inclusion criteria, and reference and target populations, which make comparison across countries potentially difficult. The irregularity of surveys can also render longitudinal or time series analyses difficult. Moreover, the quantitative description of the percentage of health facilities with ICT equipment does not speak to the (appropriate) utilization of these tools. Nor does it say anything about the level of connectivity of the ICT equipment. However, taking the previous indicator on share of health facilities with internet access together with this indicator on the share of health facilities with ICT equipment could provide insights into possible barriers to digital health and HIS adoption. For example it can help to understand availability and use, including hardware supply and procurement, or whether levels of IT professionals to connect hardware are sufficient.

At higher levels of digital adoption, it is expected that this indicator will become significantly more nuanced to reflect on the appropriate balance of ICT (in all its forms) and people resources given demands for health services.

How do these indicators help monitor and transform the availability of ICT in the health sector?

These two indicators were presented first because they are meant to capture the infrastructural prerequisites of advancing the implementation of digital health solutions. International benchmarking might be useful, but longitudinal monitoring of individual health systems and the investigation of regional variation within a country might be more meaningful for informing targeted policies. These indicators are complementary in nature (they should be considered in combination); if they are not within the expected or desired range, further investigations, perhaps qualitative in nature, would be necessary to unveil fundamental issues. A wide range of policy options has been identified for introducing better internet connectivity, broadband, etc., across countries. Signposting how many, where or what types of health facilities lack internet connectivity enables prioritization of policy actions. Depending on the dynamic between internet connectivity and availability of ICT equipment in health facilities, policy-makers would be able to explore root causes of less advancement in digital health in a country or subregion and start to take policy action, after an ICT needs assessment among health facilities in a health system. In the medium-to-long term, the measuring of internet access across broader geographies to support populations in rural and remote areas will be important to enable telemedicine services and personal empowerment through access to their health records.

Strong governance frameworks (outside and inside the health system) and robust, targeted financing on overall digital transformation would facilitate a higher share of health facilities with adequate internet access, digital infrastructure and equipment. If used properly, this equipment can contribute to improvements in access to digital applications for healthcare, which have a wide-ranging impact across health system functions and outcomes. ICT equipment can improve accessibility to care, through supporting remote tools, and aids communication and coordination among health professionals, and decision-making and treatment protocols, all of which impacts on healthcare quality and safety. If equipment is connected – across sectors, or in a regional or national system – it can enhance integration of care and system efficiency. When internet connectivity and ICT equipment are not available, digital exclusion is likely, leading to further inequalities and poorer health outcomes.

3.3. Policy question: Is the health system leveraging digital tools to deliver health services?

This policy question and the associated indicators focus on the second stage of adoption of digital health (i.e., CAMM; Price & Lau, 2014), namely its use for the delivery of services. Digital technologies are a critical factor in sustainable health systems and UHC (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023), related to digital transformation as an emerging determinant of health (OECD, 2023b). Digital health applications and tools can help transform how medical professionals provide care, what patients do to receive it, and how healthcare systems operate, thereby expanding the delivery of health services and improving access to good quality of care (Cancela et al., 2021). However, these solutions cannot (or should not) deliver services themselves without being integrated in a care pathway.

Indicators that explore the penetration of digital health solutions in service delivery can be used to capture the extent to which digital tools are embedded in the overall health delivery and governance ecosystem, and how sustainable their impact is likely to be (Kluge, Azzopardi-Muscat & Novillo-Ortiz, 2022). While this section focuses on the health system and provider perspective of the utilization of digital health technologies to deliver health services, it is important to note that (differential) patient access and use are crucially important contributors to the effects digitalization will have on health system outcomes – an aspect we revisit in the subsequent policy issue, below.

The performance indicators providing a starting point for assessing whether a health system is using digital health tools effectively to facilitate the delivery of services and enable access include:

- Use of electronic health records among providers

- Use of telehealth – penetration

- Use of e-prescription among pharmacies

Use of electronic health records among providers

Electronic health records (EHR) are real-time, patient-centred records that allow access to secure information to authorized individuals across all of their health system encounters. They can cover a patient’s medical history, diagnoses and treatment, medications, immunization, and imaging and laboratory results. Being digital, they potentially make this information easier to search, analyse and share than via a traditional paper-based medical file. However, EHRs can range from a singular tool based in the local ICT system for health records while being splintered from other local systems to an integrated record for a patient across all health facilities and sectors of care. What is more, who has access to what information in an EHR varies considerably for both providers and patients (see Oderkirk, 2021); from a health system perspective, the number of different records or entry points to a patient’s information is crucial for realized access to information. A well designed, integrated, and interoperable EHR system is fundamental to strengthening access, quality, and efficiency of care, and key for the realization of integrated care approaches and for enabling other digital health applications (for example, teleconsultations, e-prescriptions, etc.).

There is increasing data on EHR usage in health systems. The European Health Information Gateway presents information from 2015 on the number of facilities (by care sector: primary, secondary and tertiary) using a national EHR system. Meanwhile, the Monitor EHR study (2019) provided an overview of the development of interoperable EHR systems in the EU, Norway and the United Kingdom (Thiel et al., 2021) and the 2022 Regional Survey on Digital Health for the WHO European Region include EHR as a main dimension for understanding the development of digital health in a country. Fig. 3.2 below summarizes the utilization of EHRs in primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare in the European Region, with EHRs used in primary care by 84% of Member States (42 out of 50), in secondary care by 78% and in tertiary care by 69%.

However, these figures lack detail about the extent of EHR use within the health system. The share of facilities using EHR per sector per country would be a much more useful, if entry-level, indicator to understand to what extent EHR are actually being implemented in practice. Fig. 3.3 from the ICT in Health survey in Brazil shows the share of facilities by type, region and sector that had electronic systems to record patient information in 2021 (CETIC.br/NIC.br, 2021). While electronic systems are not necessarily EHRs, this can be used as a proxy to give an impression of what the visualization of this figure might look like. Therefore, the proposed indicator to monitor the baseline use of EHR in a health system is the percentage of healthcare facilities using EHR, ideally broken down by facility type and region/geography. It is important to stress here that many countries see different providers using different EHR systems that are not necessarily interoperable, and this is detrimental to the goals of digitalization, wasteful, and challenging to undo. We reflect on this further below.

Figure 3.2

Use of EHR systems in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare. Source: CETIC.br/NIC.br (2021)

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

As with several of these baseline indicators, measuring whether facilities use EHR does not capture whether these records are interoperable (which would be necessary to meaningfully enable integrated care models and profit from the digital data enclosed therein). As above, it is important to understand the dynamics of interoperability for EHR. One additional indicator could qualify whether EHR reported on are local systems of health records or an integrated patient record across the regional (or national) health system. In the case of local EHRs, there is fragmentation of information and access barriers for both patients and providers to gain a comprehensive view of a person’s consolidated health record. Central coordination – incorporating equity considerations – is crucial here, and a fully integrated system presupposes interoperability between different modalities. Provider access to her – through how many channels is information being accessed – is also important to understand to get at the effectiveness of these tools.

Figure 3.3

Healthcare facilities in Brazil by availability of electronic systems to record patient information, 2021. Source: CETIC.br/NIC.br (2021)

This indicator also does not speak to the usability, timeliness, or quality beyond interoperability of these systems or the level of connectedness, i.e., whether they are ad-hoc, local, regional or national EHRs (as in Fig. 3.4). Furthermore, data collection for this indicator is based on national surveys, which are resource intensive and may not be internationally comparable unless inclusion criteria and methods are aligned.

A complementary perspective of looking at EHR use, particularly when it comes to assessing the extent to which such systems contribute to patient empowerment and ownership of the care process, is measuring the share of patients or citizens who (can) access their health information digitally. This is more complex to capture, and a range of different concepts have been piloted in the European region. Box 3.1 briefly discusses one option of how this could be operationalized for a more rounded view of the issue. This metric may be aided through the measurements of patient-reported experience and outcome measures that are being developed through the OECD’s PaRIS initiative (OECD, 2023d).

Box 3.1

How many patients can access their personal medical information through their own digital environment?

Use of telehealth – penetration

Telehealth services are a wide set of technologies that connect patients and providers who are separated by distance (are not “co-located”) to improve realized access to care. Telehealth utilizes ICT for facilitating communication, exchanging information for diagnosis and treatment, and management of conditions. Such services include video-mediated consultations, remote home monitoring of patients, and teleradiology, but can also include distance learning and research, interaction among professionals through teleconferences, and the provision of remote clinical services (PAHO/Nic.br, 2018; WHO, 2021 and WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). Telehealth is viewed as one mechanism to strengthen primary care and address several persistent access challenges such as barriers due to geography, age, and health condition (European Commission, 2017), and in times of crisis when interaction with the health system is minimal, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic when teleconsultations became a preferred mode of primary care delivery (Silva et al., 2021; Carrillo de Albornoz, Sia & Harris, 2022; OECD, 2023e).

The suggested indicator capturing the number of primary healthcare contacts delivered telemedically by population and region/geography as a percentage of total interaction by region/geography provides a useful measure of the penetration of telemedicine into the health system as it focuses on the key service level for equitable access. Fortunately, data on in-person primary healthcare consultations (the denominator) are routinely available for OECD countries and in Eurostat. However, information on the number of teleconsultations delivered annually is not as readily available.

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

The key limitation of this indicator lies in its level of abstraction: it does not speak to the scope of telehealth functionalities that can be or are being used (for example, teleradiology, telepsychiatry, teleradiology, and teledermatology). This would give a better picture of the uptake of teleconsultations in a health system. Obviously, as a simple quantitative metric, this indicator does not say anything about the quality of the services delivered, their cost or whether they are included in the public benefits basket. Telemedicine consultations may be included in the benefits basket and free as in Slovenia or excluded from the basket as in Bulgaria and thus an out-of-pocket expense, which might undermine the potential of these services to reduce access barriers and will certainly impact on financial protection and risk aspects of care. The PaRIS survey may provide useful insights into this indicator (OECD, 2023d).

This indicator also does not speak to the appropriateness of the use of telemedicine services along with the right balance of services as health systems rebalance activities post-COVID-19.

Use of e-prescriptions among pharmacies

E-prescription is the electronic creation, transmission, and remote filling of a medical prescription. It allows health providers to use ICT to submit a new or renew an existing prescription to a pharmacy electronically. It is meant to minimize the risks associated with traditional prescribing practices, such as poor handwriting, and overcome access barriers. Additionally, it is often an integral component of EHR, where it can facilitate more informed decision-making among providers. For e-prescriptions to be realized across a health system, and for population coverage to be ensured, their embeddedness in EHR systems is not the only prerequisite; a substantial number of pharmacies across a country must be connected to the e-prescription system and able to dispense accordingly (Peltoniemi et al., 2021).

In the 2022 Digital Health Survey in the WHO European Region, 82% of Member States reported making electronic prescriptions routinely available to pharmacies when EHR systems were used to prescribe medications. Less is known about the share of pharmacies filling e-prescriptions. As an indicator, the percentage of pharmacies that dispense medication via an e-prescription (by region/geography) outlines the capacity a health system has to fill e-prescriptions and can act as a proxy for the extent to which this could be leveraged to deliver services. Although there is not yet regularly collected data to generate this indicator, several surveys set out to define the scope of e-prescription integration into the system (see for example, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022a). However, solely focusing on the share of pharmacies connected to the e-prescription system does not fully capture utilization (see below).

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

While this indicator strives to describe the capacity of pharmacies by geography in a country to fulfil prescriptions electronically, it does not provide insight into the extent to which e-prescriptions are filled and thus the potential for patient benefit. As such, the indicator could be supported by an indicator on the share of prescriptions filled electronically in a health system to further support understanding of provider behaviour and patient access. Additionally, understanding whether existing regulations and funding drive the share of e-prescriptions would be a key contextual dimension to point to barriers or enablers of the uptake of e-prescription in pharmacies – and opportunities for policy action.

A key limitation related to this indicator is the dearth of longitudinal or global data. The number of pharmacies that can dispense medication via e-prescription is collected by surveys – with their attending limitations – and most comprehensively recently (Kluge, Azzopardi-Muscat & Novillo-Ortiz, 2022). Without these insights, it is more difficult to determine the equitability of the rollout of new technical innovations.

How do these indicators help to monitor and transform the use of digital tools to deliver health services?

The number of facilities using EHR can be considered over time or in comparison with other countries to provide an impetus for action; a breakdown by sector or level of care can further signal where additional attention might be needed, although a deeper dive would be required to understand potential barriers to implementation (for example, infrastructural, skills-related, etc.). At the same time, a more granular understanding of the uniformity and/or interoperability of EHR applications within and across the system is crucial for ensuring that the desired results of improved quality, safety, efficiency, and equity can be achieved on the way to improving health outcomes and responsiveness in the system as a whole.

Considering the extent to which key services, such as primary care visits and prescriptions, are delivered digitally, ideally with the possibility for a breakdown by region and/or user characteristics, over time can provide a basis for monitoring the progress of digitalization. The use of telemedicine is linked to enhanced system efficiencies by reducing the number of medical appointments and increasing the availability of services. However, both contextual factors that might increase or decrease the availability of telehealth offers would need to be considered; what is more, health outcomes and patient-reported experience measures would ideally need to be recorded to ensure that the use of such options is meaningful and actually advances health systems goals.

This section provides some foundational indicators for countries at the start of their journeys towards digitalization of health service delivery. As discussed below, work will continue to refine and mature indicators in this space to measure the progress of the digitalization of health systems along with the assessment of value created from such investments.

3.4. Policy question: Are staff and users well prepared to use digital health services?

Even when the necessary infrastructure is in place for digital health solutions, if health professionals and service users are not sufficiently informed and do not possess the right competencies and skills, these solutions cannot be properly implemented or used to achieve wide-ranging benefits to health and health systems outcomes (see above). This results in missed opportunities for health systems strengthening and achievement of the final goals of the health system. It can also be a sign of misplacement of funds and investment.

One construct to describe and capture these competencies and skills is digital literacy, where digital health literacy refers to the ability to search, find, understand, and evaluate health information from electronic resources and to use this knowledge to solve health-related problems (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). Digital literacy includes understanding the importance of the capture and use of quality data. Lack of digital literacy is recognized as a significant barrier to realizing the potential of digital health for many communities.

The importance of digital health literacy for realizing the benefits of the digital transformation of health systems is widely recognized; the WHO Regional Office for Europe suggests making it a core component of national health objectives (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023) and is consistent with the OECD policy framework for digital health ecosystems (OECD, 2023b). However, in the recent WHO survey of Member States in the European Region, only 17 of the 52 responding (33%) countries reported having developed digital health education action plans, policies, and strategies, with a further 10 reporting that these were in development. This means that a little over half (52%) of the Member States have formally moved towards advancing digital health literacy in their health systems. Gaps in overall digital literacy – for example, only 56% of Europeans in the EU were found to have basic digital skills (European Commission, 2017) – mean that more foundational work needs to be done in terms of planning and training to increase digital health literacy overall. This is an important area to monitor.

As mentioned, digital health skills and competencies are necessary both for health professionals and health service users. The two performance indicators presented in this section look at the overall intention and preparedness of the health system to advance digital health literacy, focusing on care providers, as the relevant competencies and skills of those working in healthcare are essential to fulfilling national digital health strategies (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). However, ensuring digital literacy of the population, the healthcare users, is obviously also a key consideration, both for 1) building trust in digital health tools and facilitating their integration in delivery models, 2) ensuring optimal use of delivery and user-oriented solutions, such as in telemedicine (for example, teleconsultations) and mHealth, and 3) as a measure to mitigate digital exclusion.

As with previous sections, here we focus on the starting points for digital transformation, looking at whether digital health literacy options are available and used (i.e., CAMM; Price & Lau, 2014). We comment on the limitations of this narrow scope below. The two indicators selected to start assessing the extent to which a health system is preparing the health workforce for the optimal use of digital health technologies are:

- The existence of digital health literacy plans

- Uptake of digital skills training in health workforce

The existence of digital health literacy plans

Whether a country has already established or encouraged the introduction of mandatory continuing professional development (CPD) in digital health for health professionals can be considered a strong indication of 1) awareness of how important digital skills of the workforce are, and 2) recognition that standardization of the content and/or type of skills to be developed can help with a balanced implementation of digital health solutions.

Instead of measuring the extent to which digital health skills have been incorporated into academic curricula for health and social workers, focusing on CPD can provide a snapshot of the penetration of digital skills among the current workforce, rather than the future workforce, and therefore may point to potential policy actions with a more immediate effect. Capturing this binary indicator – the existence of digital health literacy plans – provides not only an opportunity for benchmarking, but also the chance to identify potential candidates for cross-country learning among those countries who have such plans.

In the latest survey on digital health for the WHO Regional Office for Europe, the availability of digital health literacy action plans (see dark columns in Figure 3.4, below) varied by region and within the European Region; similarly, some (sub)-regions were ahead in terms of putting in place digital inclusion plans, i.e. strategies to advance the digital skills of disadvantaged population groups in a targeted manner. Crucially, digital health literacy includes a range of different elements, including learning how to use technology, how to work with data and statistics, how to provide quality data and how to handle digital security and data protection. The content and scope of these plans, for instance in relation to the skills gaps of a given workforce, should also be considered.

Figure 3.4

Digital health literacy action and inclusion plans. Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

The existence of a national intention for skills training does not guarantee that relevant programmes have been implemented, nor their quality, nor that they will be taken up by the workforce. Nor does it provide information on the scope and content of the plans and how they match the skills and competency needs of the workforce. To explore these dimensions further, more granular sub-indicators or uptake metrics (see next indicator) are necessary.

Another key limitation has to do with the definition of ownership of CPD programmes, which influences the implementation of plans. Depending on the health system set-up, it is often professional societies who are in charge of self-regulating when it comes to the definition of CPD curricula and requirements for the different professions; this might not be organized at the national level, and even if it is, it might not be state-owned. This means that the indicator has to be operationalized in a way that accounts for this variability in health system and country administrative set-ups.

Uptake of digital skills training in health workforce

Digital literacy among the health workforce, health service users, and the general public is critical to the successful implementation of digital health in a health system. For the workforce in particular, being able to manage and navigate ICT systems that support digital health tools is crucial (Reixach et al., 2022). While there is little information on digital literacy levels across the health workforce overall, and the gap between health workforce digital literacy levels and their usage of digital solutions is not fully understood yet (EHP, 2016), good-quality training has been identified as a main factor in overcoming barriers of healthcare workforce utilization of digital health technologies, together with incentives and evaluation of the perceived usefulness of different tools (Borges do Nascimento et al., 2023). Digital literary training should therefore be embedded in the theoretical and practical curricula of the different health and health system professions, as well as in CPD programmes (see above).

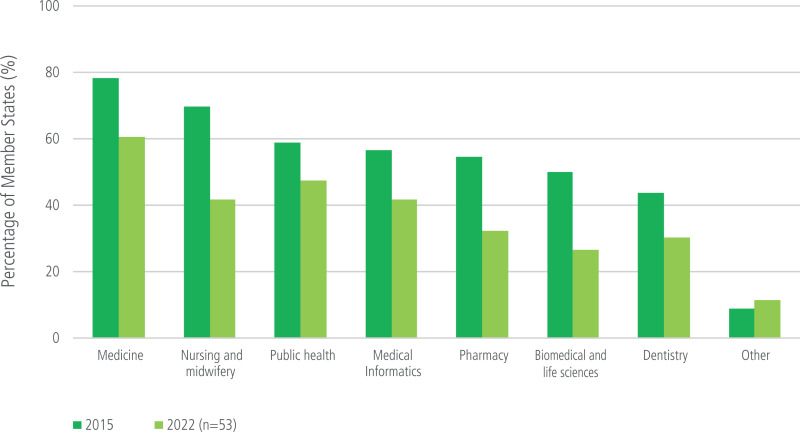

The WHO Regional survey 2022 maps out where in-service digital training is offered in the WHO European Region. Notably, 29 of 41 responding Member States (71%) reported in-service training in digital health, with even fewer making this mandatory. It also found when looking across professions that in-service training was made more frequently available to medical professionals, followed by nursing staff and public health specialists. Pharmacists, in contrast, seldomly received in-service training (Fig. 3.5), despite the frequent implementation of e-prescriptions (see above). The extent to which these trainings were conducted benchmarked against an implementation plan across professions or geographies or rate of recipient/participant completion was not assessed (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023). However, whether such training options can unfold their potential depends on whether they are actually taken up by health professionals – and whether the skills are subsequently used.

The indicator suggested here, share of health workforce by type (for example, health professionals, non-clinical and administrative staff, health informatics) who received a training in the last x number of years, is a first step to assessing the degree of health literacy in the current workforce and to pinpointing where extra efforts are necessary. When considered together with the previous indicator, it can also provide some insight into the appropriateness of available digital health literacy plans; if they are available but the uptake of training programmes is low, the reasons for this discrepancy should be investigated.

Figure 3.5

Training for health professionals on digital health. Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2023

Limitations and challenges of interpreting this indicator

This indicator does not capture any elements of quality, nor does it consider whether training is mandatory, voluntary, or tied to licensing, credentialling, certification, and recertification. While incorporating a time window can increase the likelihood that the trainings represented correspond to relatively up-to-date, relevant content, this cannot be ensured by measuring this indicator alone. If broken down by profession, it can give a sense of which groups have completed the trainings or have shown willingness to participate in the trainings, which can impact (positively or negatively) on the uptake of digital health skills. However, this does not assess whether trained staff put the skills to use. Additionally, this indicator as suggested here for ease of use does not have a geographic component; however, a breakdown by territorial unit would enable a more nuanced understanding of how workforce literacy may or may not contribute to the uptake of digital health solutions and ultimately to health outcomes and health system performance. It would also be helpful for designers of CPD programmes to disaggregate by type of training (see indicator above) to see if certain content and not only specific professional constituencies lend themselves to greater or lesser uptake; exploring why would be a next line path of inquiry. Further, this indicator speaks only to current health professionals and not to the digital literacy levels in the future workforce. Another important complementary aspect that would be important to capture involves the level of perceived usefulness and trust in digital solutions – ideally improved with literacy training – of end users, which could also help contextualize and gauge any change in IT burden (increase or decrease) on the health workforce as a result of trainings and the introduction of digital tools.

There is little information at the international level capturing the share of health professionals who receive in-service training, let alone the share of those using the skills they were trained in. Potential sources for such a figure could be national statistics. In the future, the current DDS-MAP project, part of the EU4 health programme, which is mapping out digital competencies in Europe, and the continuing work of the WHO Regional Office for Europe may be able to provide data.

How do these indicators help to monitor and transform the digital skills of health workers and users?

Monitoring digital health literacy is crucial for predicting the likelihood that digital health tools will be taken up and used appropriately and effectively. Ensuring national standards for digital skills training and monitoring the share of the workforce that undergoes such training can both help gauge the extent to which the workforce is in a position to leverage digital health tools; as with previous indicators in this brief, benchmarking the value of this indicator over time and across countries can provide impetus for action. However, complementary indicators are important to consider in a second step, such as digital inclusion strategies, and a breakdown of professionals with digital skills by occupation, sector, and geographic location, to ensure that the potential to use digital tools effectively is distributed equitably within the territory. It would be worthwhile also to qualitatively assess how far national plans align with digital health action plans of international organizations like the WHO (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022b). Finally, because measuring the digital health literacy of health service users in a similar manner is methodologically more challenging and resource intensive, the indicators provided here focus on professional skills to provide an entry point for further considerations. They do not give any insight into the extent to which users are able to benefit from accessing digital services (or which users might be more likely to do so).

3.5. Looking to the future

The indicators suggested in this section as tracers aim to provide an entry point into considering the fundamental building blocks of the digital transformation of health service delivery: effective governance, availability of necessary infrastructure, the health system’s formal intent to leverage digital health solutions to provide services and how this intent is realized in practice, and whether the health workforce is likely to possess the necessary skills to benefit from supporting digital applications and delivery solutions to deliver this type of care safely and effectively. These baseline indicators are indicative measures that can be further contextualized by additional (quantitative and qualitative) insights for a more fulsome understanding of the standards and dynamics of the digital ecosystem, as discussed for each individual indicator.

Considering the challenges of digital exclusion, the collection of the discussed indicators in a manner that allows disaggregation by territorial unit and ideally user demographics (where applicable) would be crucial for ensuring policy-makers have information not only about the health system as a whole but also on population groups likely to be left behind. What is more, the indicators suggested here would need to be considered in combination to increase the relevance of the information they provide – for instance, for triangulating whether training penetration matches the facility digital infrastructure level – and to help identify digital deserts, and thus meaningful priority areas for action.

This section has highlighted the lack of agreed core indicators to monitor the successful adoption of digital health (see also Brenner et al., 2023), but also a range of initiatives that have provided impetus for progress in this area. A common limitation of the indicators suggested in this section is their lack of depth regarding the quality (and interoperability and connectedness) of digital health infrastructure, delivery, and skills; while they capture the extent to which they are likely to be in place, they say nothing about their appropriateness for ensuring safe, effective, and more integrated care for patients or reducing the work burden for clinicians, in line also with national priorities and international guidance. Ensuring that health service providers and users are involved in the development of the digital tools with which they are meant to interact is crucial to ensure that they achieve these goals; stakeholder involvement in the development of digital literacy options is equally important. Both elements should be part of new or updated digital health strategies, as argued earlier in the section. One of the most important elements to view from the user perspective (with clinicians and patients both being users in this case) is the extent to which (sufficient) information from EHRs is available quickly and simply through low-threshold, user-friendly solutions that are still secure and consider data privacy concerns.

What is more, both the WHO (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022b, 2023), the European Commission’s Expert Panel for Investing in Health (European Commission, 2022), and the OECD (OECD, 2023b) have stressed the importance of establishing systems to evaluate how digital health solutions perform themselves. For example, how they are contributing to achieving national health-related objectives and demonstrating benefits for patients in access and outcomes. Importantly, the existence of such mechanisms could also be measured and monitored over time. An example for this would be a qualitative indicator about the existence of formal reimbursement decision pathways for mHealth applications; more meaningful would be the combination of such an indicator with metrics on the number of mHealth applications available to patients through such a mechanism based on robust evidence on benefit, and the breadth of indications they cover that could be contextualized with population health needs.

One particularity of this section compared to others in this brief is that the advancement of digitalization in a health system is often dependent on the wider digitalization ecosystem in a country. Another is that the advancement of health system digitalization can improve data availability and therefore broaden the spectrum of potential indicators that can be collected to assess not only the role of digital health in achieving health system intermediate objectives and final goals, but also broader policy questions like the ones discussed in other sections. Harnessing information from the different types of digital health applications increasingly in use, such as EHRs and patient wearables, could be leveraged to produce indicators that can monitor the deployment of new models of care, such as remote monitoring (for example, share of chronic patients monitored remotely), or related to care coordination. Ideally, as above, such data can also be used to evaluate the performance of such solutions themselves (for example, share of remotely monitored patients achieving diabetes or hypertension control). What is more, interoperable EHR systems across providers and sectors can facilitate the calculation of indicators that consider the patient pathway; digital health applications can be leveraged to collect patient-reported outcome and experience measures that can feed into performance assessment, specifically for digital health and in general.

With the increasing use of artificial intelligence to facilitate processes in healthcare and improve access and outcomes, further indicators could be developed to evaluate the extent of AI-supported functionalities in digital health systems, such as EHRs, as well as the controls, development, and evolution of Responsible AI solutions. However, the attractiveness of exploring such elements should not detract from the main tenets of exploring whether the conditions for the meaningful and equitable implementation of digital health – including the capture, processing, and use of quality health data – are in place to begin with. Beyond the indicators suggested in this chapter, as indicated, a set of indicators on the robustness of constructive digital health data governance and the scope of data usage would be another important horizon for future work, building on the OECD’s Recommendation for Health Data Governance (2016). Additionally, monitoring expenditure for digital health services (by financing scheme and territorial unit, for instance), the penetration of digital health solutions in different health sectors (primary, specialist, and long-term care), along with the advancement of integrated care teams, the value generated by investments in digital health and health data, and efforts to increase the digital literacy of both health professionals and the population would also be crucial for maintaining a holistic picture moving forward.

References

- Borges do Nascimento IJ, et al. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):161. [PMC free article: PMC10507089] [PubMed: 37723240] [CrossRef]

- Brenner M, et al. Development of the key performance indicators for digital health interventions: A scoping review. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231152160. [PMC free article: PMC9880566] [PubMed: 36714542] [CrossRef]

- Cancela J, et al. Chapter 2 – Digital health in the era of personalized healthcare: opportunities and challenges for bringing research and patient care to a new level. In: Syed-Abdul S, et al., editors. Digital Health – Mobile and Wearable Devices for Participatory Health Applications. Elsevier; 2021. Available at: https://www

.sciencedirect .com/science/article /abs/pii/B978012820077300002X?via %3Dihub(accessed 6 December 2023) - Carrillo de Albornoz S, Sia KL, Harris A. The effectiveness of teleconsultations in primary care: systematic review. Fam Pract. 2022;39(1):168–82. [PMC free article: PMC8344904] [PubMed: 34278421] [CrossRef]

- CETIC.br/NIC.br. Executive Summary: ICT in Health Survey 2021. Brazilian Network Information Center (NIC.br) and Regional Center for Studies on the Development of the Information Society (Cetic.br); 2021. Available at https://cetic

.br/en/publicacao /executive-summary-survey-on-the-use-of-information-and-communication-technologies-in-brazilian-healthcare-facilities-ict-in-health-2021/ (accessed 6 December 2023) - De Bienassis K, et al. Health data and governance developments in relation to COVID-19: How OECD countries are adjusting health data systems for the new normal. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2022. OECD Health Working Papers 138. Available at: https://doi

.org/10.1787/aec7c409-en (accessed 6 December 2023) - European Commission. The Digital Skills Gap in Europe. Brussels: European Commission; 2017. Available at: https:

//digital-strategy .ec.europa.eu/en /library/digital-skills-gap-europe (accessed 6 December 2023) - European Commission. Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH), Opinion on Facing the impact of the post-Covid-19 condition (Draft). Brussels: European Commission; 2022. Available at: https://health

.ec.europa .eu/system/files /2022-10/exph_031_covid_en.pdf (accessed 6 December 2023) - EHP. Digital skill for health professionals. European Health Parliament; 2016. Available at: https://www

.healthparliament .eu/wp-content /uploads/2017/09/Digital-skills-for-health-professionals .pdf (accessed 18 December 2023) - Fahy N, et al. Use of digital health tools in Europe: Before, during and after COVID-19. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2021. Available at: https://iris

.who.int /bitstream/handle/10665 /345091/Policy-brief-42-1997-8073-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 6 December 2023) [PubMed: 35099866] - GDHM. State of Digital Health around the world today, Global Digital Health Monitor Indicator Guide. Global Digital Health Monitor; 2023. Available at: https://monitor

.digitalhealthmonitor .org/indicators_info (accessed 6 December 2023) - Kluge HHP, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Novillo-Ortiz D. Leveraging digital transformation for better health in Europe. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(12):751–751A. [PMC free article: PMC9706350] [PubMed: 36466211] [CrossRef]

- Oderkirk J. Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. OECD Health Working Papers 127. Available at: https://www

.oecd.org /sti/survey-results-national-health-data-infrastructure-and-governance-55d24b5d-en.htm (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems. Available at: https://doi

.org/10.1787/e3b23f8e-en (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. Health Data Governance for the Digital Age: Implementing the OECD Recommendation on Health Data Governance. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2022. Available at: https://doi

.org/10.1787/68b60796-en (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023a. Available at: https://www

.oecd.org /publications/ready-for-the-next-crisis-investing-in-health-system-resilience-1e53cf80-en.htm (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. Health at a Glance 2023. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023b. Available at: https://www

.oecd.org /health/health-at-a-glance/ (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. OECD Going Digital Toolkit. Paris: OECD; 2023c. Available at: https:

//goingdigital.oecd.org/ (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. Patient-Reported Indicator Surveys (PaRIS). Paris: OECD; 2023d. Available at: https://www2

.oecd.org/health/paris/ (accessed 6 December 2023) - OECD. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Telemedicine, OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023e. Available at: https://www

.oecd.org /health/the-covid-19-pandemic-and-the-future-of-telemedicine-ac8b0a27-en.htm (accessed 6 December 2023) - PAHO/Nic.br. Measurement of Digital Health: Methodological recommendations and case studies. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the Brazilian Network Information Center (NIC.br); 2018. Available at: https://www

.nic.br/media /docs/publicacoes /1/measurement%20of%20digital%20health .pdf (accessed 6 December 2023) - Panteli D, et al. Health and Care Data: Approaches to data linkage for evidence-informed policy. Health Syst Transit. 2023;25(2):1–248. [PubMed: 37489953]

- Park S. Multidimensional Digital Exclusion and Its Relation to Social Exclusion. In: Tsatsou P, editor. Vulnerable People and Digital Inclusion. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2022. Available at: https://doi

.org/10.1007 /978-3-030-94122-2_4 (accessed 6 December 2023) - Peltoniemi T, Suomi R, Peura S, Lähteenoja MNY. Electronic prescription as a driver for digitalization in Finnish pharmacies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1017. [PMC free article: PMC8474735] [PubMed: 34565354] [CrossRef]

- Price M, Lau F. The clinical adoption meta-model: a temporal meta-model describing the clinical adoption of health information systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:43. [PMC free article: PMC4050391] [PubMed: 24884588] [CrossRef]

- Quinn M, et al. Electronic health records, communication, and data sharing: challenges and opportunities for improving the diagnostic process. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(3):241–8. [PMC free article: PMC6691503] [PubMed: 30485175] [CrossRef]

- Reixach E, et al. Measuring the Digital Skills of Catalan Health Care Professionals as a Key Step Toward a Strategic Training Plan: Digital Competence Test Validation Study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e38347. [PMC free article: PMC9752462] [PubMed: 36449330]

- Sabes-Figuera R, Mahrios I. JRC Scientific and Policy Reports, Joint Research Centre. Brussels: European Commission; 2013. European Hospital Survey: Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth Services (2012–2013) Available at: https:

//digital-strategy .ec.europa.eu/en /library/european-hospital-survey-benchmarking-deployment-ehealth-services-2012-2013 (accessed 6 December 2023) - Silva CRDV, et al. Telemedicine in primary healthcare for the quality of care in times of COVID-19: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e046227. [PMC free article: PMC8277488] [PubMed: 34253666]

- Socha-Dietrich K. Empowering the health workforce: Strategies to make the most of the digital revolution. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. OECD Health Working Papers No. 129. Available at: https://www

.oecd.org /health/empowering-the-health-workforce-to-make-the-most-of-the-digital-revolution-37ff0eaa-en.htm (accessed 6 December 2023) - Thiel R, Lupiáñez-Villanueva F, Deimel L, Gunderson L, Sokolyanskaya A. eHealth, Interoperability of Health Data and Artificial Intelligence for Health and Care in the EU. European Union; 2021. Available at: https:

//digital-strategy .ec.europa.eu/en /library/interoperability-electronic-health-records-eu (accessed 18 December 2023) - Tran DM, Thwaites CL, Van Nuil JI, McKnight J, Luu AP., Paton C; Vietnam ICU Translational Applications Laboratory (VITAL). Digital Health Policy and Programs for Hospital Care in Vietnam: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e32392. [PMC free article: PMC8867296] [PubMed: 35138264] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. IIEP Learning Portal, Glossary, Information and communication technologies (ICT). UNESCO; 2023. Available at: https:

//learningportal .iiep.unesco.org/en /glossary/information-and-communication-technologies-ict (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available at: https://iris

.who.int /bitstream/handle/10665 /43918/9789241596077_eng .pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO. Atlas of eHealth country profiles: the use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage: Based on the findings of the third global survey on eHealth 2015. Geneva: WHO Global Observatory for eHealth; 2016. Available at: https://www

.who.int/publications /i/item/9789241565219 (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available at: https://www

.who.int/publications /i/item/9789240020924 (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO Regional Office for Europe. Monitoring the implementation of digital health: an overview of selected national and international methodologies. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022a. Available at: https://iris

.who.int/handle/10665/364227 (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO Regional Office for Europe. Regional digital health action plan for the WHO European Region 2023–2030 (RC72), Seventy-second Regional Committee for Europe, Tel Aviv. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022b. Available at: https://www

.who.int/europe /publications/i/item/EUR-RC72-5 (accessed 6 December 2023) - WHO Regional Office for Europe. The ongoing journey to commitment and transformation: digital health in the WHO European Region, 2023. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2023. Available at: https://www

.who.int/europe /publications/m /item/digital-health-in-the-who-european-region-the-ongoing-journey-to-commitment-and-transformation (accessed 6 December 2023)

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen (Denmark)

NLM Citation

Karanikolos M, Adib K, Azzopardi Muscat Net al., authors; Figueras J, Karanikolos M, Guanais F, et al., editors. Assessing health system performance: Proof of concept for a HSPA dashboard of key indicators [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2023. (Policy Brief, No. 60.) 3, Assessing digital health.