Using Wellness Coaches and Extra Support to Improve the Health and Wellness of Adults with Serious Mental Illness

Authors

James Schuster, MD, MBA,1,2,3 Charles Reynolds, III, MD,1,3 Tracy Carney,2 Jane Kogan, PhD,1 Chaeryon Kang, PhD,3 Patty Schake, MSW,2 and Cara Nikolajski, MPH1.Affiliations

Structured Abstract

Background:

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) are vulnerable to chronic medical diseases and substantially decreased life expectancy. Many causes of morbidity and mortality are preventable or reversible with appropriate lifestyle modifications. Unfortunately, complex system-, provider-, and individual-level barriers can impede individuals with SMI from care that effectively prevents or manages chronic conditions. Community mental health centers (CMHCs) can help address the unmet medical needs of individuals with SMI, as they are often a primary point of contact with the health care system for this population.

Objectives:

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center for High-value Health Care and patient, provider, and payer partners evaluated 2 promising interventions—provider-supported integrated care (provider-supported) and patient self-directed care (self-directed)—for promoting the health and recovery of adults with SMI.

- Primary Aim 1: Compare the effectiveness of the interventions on 3 primary patient-centered outcomes: patient activation in care, health status, and engagement in primary/specialty care.

- Primary Aim 2: Examine the moderating role of gender for the 3 primary patient-centered outcomes.

- Secondary Aim 1: Explore the impact of the interventions on secondary outcomes: hope, quality of life, functional status, care satisfaction, medication adherence, emergent care, and laboratory monitoring.

- Secondary Aim 2: Explore the mediating role of patient engagement in the interventions for primary and secondary outcomes.

Methods:

The study population comprised Medicaid-enrolled adults diagnosed with SMI who received care at 1 of 11 CMHCs. We used a cluster randomized design and mixed-methods approach. We captured patient self-report measures and insurance claims at 5 time points across 2 years of implementation. We conducted qualitative interviews with service users and staff members to understand barriers and facilitators to intervention success and dissemination. Using generalized linear mixed models and generalized estimating equations, we analyzed the impact of interventions on primary and secondary outcomes. To assess heterogeneity of treatment effects, we analyzed the role of gender as a moderator. We used an editing approach to develop a qualitative analysis codebook and analyzed narratives for relevant themes. Finally, we employed a learning collaborative approach to support implementation.

Results:

Among the 1229 men (37%) and women (63%) with SMI who were enrolled in the study, 713 participated in provider-supported and 516 participated in self-directed. The mean age of participants was 43, and most were White (90%). Over the 18 to 24 months of follow-up, intervention type had a differential impact on patient activation: Provider-supported participants experienced an increase in activation score at 6 months and self-directed participants experienced an increase at 18 months (P < .0001). Additionally, women in provider-supported were more likely to report increased activation compared with men (P < .0001). Both interventions positively affected mental health status (P < .0001) and engagement in primary/specialty care (P < .0001). Several secondary outcomes improved, although perceived physical health status declined (P < .0001). CMHC staff and service users reported positive experiences in both interventions. We identified barriers (eg, staff turnover, lack of service user motivation to change health habits) and facilitators (eg, integration of intervention components into routine practice, availability of a wellness nurse [provider-supported only]) to intervention success. Use of the learning collaborative allowed for consistent improvement on process and outcomes goals over time and promoted high levels of implementation. All sites continue to implement the interventions poststudy, and staff at additional CMHCs have been trained and supported to deliver similar models of care.

Conclusions:

Both provider-supported and self-directed affected patient-centered outcomes, including patient activation, engagement in primary/specialty care, and quality of life. This study promotes national efforts to avoid comorbidity and early mortality among individuals with SMI and provides information about scalable models that hold promise for successful uptake in other behavioral health treatment settings.

Limitations:

Our use of historical claims data limited the accuracy of prestudy eligibility estimates at each study site, resulting in lower enrollment, a sample size imbalance across study arms, and reduced statistical power to conduct proposed heterogeneity of treatment effect analyses beyond the role of gender. The completeness of self-report data across all 5 time points is a clear limitation but not unexpected in the context of real-world community mental health settings. Our use of claims data enhanced data completeness, thereby permitting examination of the intervention's impact on several important patient-centered outcomes.

Background

Problem Overview and Evidence Gaps

The combination of high medical need and challenges in accessing quality medical care make adults with serious mental illness (SMI) one of the most medically vulnerable populations in America. Although 1 in 4 (approximately 57.7 million) adults experience a mental health problem in any given year, the main burden of illness in the US population derives from the estimated 6% (or 1 in 17) who live with SMI,1 defined as mental, behavioral, or emotional conditions (eg, schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar disorder, major depression) that significantly inhibit functionality.2,3

Adults with SMI have high rates of earlier-onset chronic conditions and premature death, dying as many as 15 to 25 years younger than the general population.4-6 The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome is high among the SMI population. Key contributors include modifiable lifestyle choices and behaviors, such as tobacco use, poor diet, and sedentary lifestyle7-11; negative metabolic effects of atypical antipsychotic medications12-16; higher rates of undiagnosed, untreated, or poorly treated medical illnesses17-19; and difficulty obtaining routine preventive and primary care.20-24

For the large portion of individuals with SMI who are insured through Medicaid, community mental health centers (CMHCs) are likely to be their first, and often only, points of contact with the health care system.25 CMHCs have long recognized their important role in addressing the unmet medical needs of the SMI patients they serve.26 Traditional mental health case management typically serves as the usual care approach for addressing these needs. Case managers meet with individual patients in their home or other community settings to assist with housing, eligibility for various benefits, activities of daily living, and adherence to medication; they also coordinate care between health care providers and facilitate access to health care services. Although evidence shows that intensive case management is associated with increased social function and quality of life, limited efforts have been made to provide training support to case managers on the overall health and wellness needs of individuals with SMI or to evaluate the impact of case management on patients' physical health outcomes.27-29

The role that individual patient characteristics can play in addressing the unmet health care needs of those with SMI is also not well understood. For example, although gender is a well-documented factor associated with access to and use and impact of health care interventions,30-32 we do not know how best to leverage gender differences to ensure that care is offered and targeted in a way that maximizes the impact on patient-centered outcomes. In addition, we are uncertain if an individual's level of engagement in his or her own care affects the impact that these interventions have on patient-centered outcomes.

Mental Health Care Innovations

Numerous governmental and consumer advocacy reports have increased national awareness about the need to better coordinate behavioral and physical health care.33,34 As a result, Medicaid programs across the nation have implemented several behavioral health home approaches to support those who may benefit from integrated behavioral and physical health care services.35 However, these approaches are not typically designed to provide a full array of behavioral and physical health clinical services; rather, they support discrete interventions, such as patient self-management, patient-provider shared decision making about important health and wellness choices, and community linkages to support patient health needs.36

Attending to both behavioral and physical health issues has led to improvements in primary care utilization, quality of life, disease management, and patient activation.37 However, researchers have not yet conducted well-designed randomized studies of these innovative models nor assessed their key components. In addition, although adaptations to traditional CMHC services, specifically case management, offer a promising approach for improving the health of patients with SMI,38,39 most organizations that serve these individuals have been unable to promote a complete culture of wellness, disease risk factor behavior change, and disease prevention and management by training and supporting CMHC staff to address unmet patient needs. Resource limitations in the form of staffing, infrastructure, and/or financing at these organizations have so far prevented such changes.

Since 2010, a multistakeholder collaboration in rural Pennsylvania led by the Community Care Behavioral Health Organization has been working to transform CMHCs into optimally performing behavioral health homes. Together, stakeholders have designed and implemented an array of supports and services for improving the health, wellness, and recovery of adults with SMI who receive care in rural CMHCs. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) for High-value Health Care, a nonprofit research organization focused on health care systems improvement, engaged with these partners to build on and advance these efforts by comparing the effectiveness of 2 methods of delivering integrated care for improving outcomes that matter most for patients with SMI: provider-supported integrated care (provider-supported) and patient self-directed care (self-directed). Although the integration of physical health and wellness is a critical component of both models, provider-supported and self-directed each consist of unique features for supporting both the behavioral and the physical health of service users in CMHCs.

Provider-Supported Integrated Care

This intervention is based on previous research38-40 demonstrating that adaptations to traditional mental health care management offer a promising approach for improving medical care and health for patients with SMI treated in CMHC settings. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, between 1950 and 2007, researchers conducted 33 randomized controlled trials and high-quality quasi-experimental studies on integrating mental health into primary care in the United States.41 However, over this same period, they conducted only 3 studies on integrating medical care into specialty mental health.41 In a recent systematic review, our study consultant, Dr Benjamin Druss, confirmed that all 3 of these trials consistently reported improvements in medical care, quality of care, and patient outcomes.42 In this study, provider-supported used registered nurses on staff at participating CMHCs; these nurses worked with service users on coordinating their care, enhanced communication between CMHC providers and the Medicaid payers, and provided patient wellness support and education.

Self-directed Care

This intervention focuses on patient activation, which the Institute of Medicine has endorsed43 and many other stakeholders have recognized as fundamental to both mental illness recovery44-47 and effective chronic illness care.48,49 Activating patients to be more informed and effective managers of their health and health care lies at the heart of patient-centered care. Research confirms that being an active participant in one's own care is linked to better health outcomes50,51 and that a positive relationship exists between self-efficacy, preventive actions, and health outcomes.50,52-54 Moreover, providing information about health conditions and personal health care use, as well as tools for tracking progress on personal wellness goals, can play a critical role in facilitating wellness and recovery and enhancing shared decision-making skills among patients with SMI.55,56 Wellness programs focused on chronic disease self-management57,58 and other health promotion activities59,60 have achieved promising results for this population. In this study, self-directed used web- and paper-based health management tools and resources, such as the “I'm in Charge” manual, flip charts, and worksheets, to monitor self-management tasks and aid patients in taking a more active role in their own health care.

Study Objective and Aims

Building on the work of a multistakeholder collaboration in rural Pennsylvania, the UPMC Center for High-value Health Care and our patient, provider, and payer partners compared the effectiveness of 2 promising interventions—provider-supported and self-directed—delivered through CMHCs to promote the health, wellness, and recovery of adults with SMI. We implemented and evaluated these care delivery methods to determine their potential to serve as best practices for improving outcomes for individuals with SMI who have or are at risk for chronic medical conditions and who receive care at rural CMHCs. This study had 2 primary aims and 2 secondary aims.

Primary Aim 1: Compare the effectiveness of the interventions for 3 primary patient-centered outcomes: patient activation in care, health status, and engagement in primary/specialty care.

Primary Aim 2: Examine the moderating role of gender for the 3 primary patient-centered outcomes.

Secondary Aim 1: Explore the impact of the interventions on secondary outcomes: hope, quality of life, functional status, care satisfaction, medication adherence, emergent care, and laboratory monitoring.

Secondary Aim 2: Explore the mediating role of patient engagement in the interventions for primary and secondary outcomes.

Goal of This Report

This report will provide meaningful information for a range of stakeholders. Adults with SMI seeking to make positive health choices will have a better understanding of which approaches will work best for them. Clinicians and health care service providers will learn about the benefits of addressing the holistic health and wellness of adults with SMI and be better prepared to support positive health choices and improve outcomes of the individuals they serve. Researchers will gain a better understanding of the complexities of conducting real-world comparative effectiveness research and the implementation and evaluation challenges they may face. Other stakeholders, such as payers, government entities, and policymakers, may use these results to inform insurance payment models, health care regulations, and policy.

Stakeholder Participation

We designed this study to focus on interventions, research questions, and outcomes that are derived from and directly related to patients' SMI experience and the care they receive. Stakeholder engagement has been a vital and effective strategy for ensuring our study's relevance to the ultimate users of the information produced. The study team followed a highly collaborative process that directly incorporated stakeholder perspectives, interests, and values in all phases and aspects of our work.

Types and Numbers of Stakeholders

Study team members worked closely with stakeholders from a variety of representative groups and entities, including individuals with SMI (n = 26); family members (n = 1); behavioral/physical health care provider organizations (n = 11); physical health providers (n = 3); peer support staff (n = 25); advocacy group representatives from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (n = 2); mental health policymakers, such as county- and state-level administrative leadership (n = 3); subject matter experts (n = 10); and health system and payer leadership (n = 3).

Conceiving and Achieving Balanced Stakeholder Perspectives

Our team has a strong history of collaborating with and engaging stakeholders in all elements of our work. The inclusion of a stakeholder co-principal investigator (co-PI), the formal involvement of the stakeholder advisory board (SAB), and all other methods of stakeholder engagement that occurred regularly across all phases of the study ensured that stakeholder perspectives and values were well represented and incorporated into the study's design, implementation, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of findings. The study team lives by the value often voiced in the advocacy community—“nothing for us without us”—and collaborative relationships with stakeholders are a key component of our work.

Stakeholder Identification

The study team built on established collaborative work led by the Community Care Behavioral Health Organization, the UPMC Center for High-value Health Care, the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, and the Behavioral Health Alliance of Rural Pennsylvania to identify and engage a diverse group of stakeholders to contribute meaningfully at every stage of the research process.

Methods, Modes, and Intensity of Engagement

Stakeholder Co-PI

Our stakeholder co-PI was integral to ensuring that the patient's voice was included in all facets of the study. She piloted our study measures with service users to assess data collection burden. As cochair of the SAB, she ensured that all participating stakeholders had the opportunity to inform study design, implementation, interpretation of findings, and dissemination. She also actively participated in all regularly scheduled study investigator team meetings and data analyses review/discussion meetings, either by phone or in person.

Stakeholder Advisory Board

Our SAB consisted of 15 to 20 participants (depending on availability) from a variety of stakeholder groups. The board met in person twice annually to discuss important topics, such as qualitative interview questions; novel dissemination strategies, such as the development of an intervention resource website (currently underway); and the reasons we may have observed similarities or differences in findings between the study arms.

Learning Collaboratives

Throughout the first year of intervention implementation, leadership teams, including a service user or peer specialist, administrator, clinical representative, and quality leader from each CMHC, participated in 3 in-person daylong and 9 webinar-based learning collaborative meetings. During these meetings, which emphasized interactive training methods and group learning, members of the stakeholder leadership teams reviewed data, shared their implementation successes and challenges, problem solved, and monitored implementation with process and outcomes data. The learning collaborative facilitators engaged the leadership teams in discussions about establishing a culture of wellness at the monthly meetings. Leadership teams reported on their progress and achievement of implementation milestones. The learning collaborative fostered a community of practice for all stakeholders, including service users and peer specialists, to share strategies for the successful implementation and incorporation of the interventions into routine practice to ensure sustained practice change.

Stakeholder Forums

At the completion of the study, we held 2 in-person, half-day stakeholder forums in central and eastern Pennsylvania with a range of attendees, including behavioral health providers and administrators, policymakers, and payers. We also presented study findings at a special SAB meeting in March 2017 that included individuals receiving behavioral health services. During these forums and meetings, we shared the study results and solicited feedback regarding interpretation of the findings and potential next steps.

Perceived Stakeholder Impact

Relevance of the Research Questions

Before proposal submission, the stakeholder co-PI worked closely with the study team to develop the study's research questions and ensure their patient-centeredness. The study team also convened focus groups with service users, family members, and other stakeholders to discuss and refine the questions.

Study Design, Processes, and Outcomes

We identified preliminary outcome measures based on pilot study service user feedback. In addition, our stakeholder co-PI made multiple contributions to the study design and processes. For example, she facilitated a focus group with service users to assess the burden and duplication of study measures. She also emphasized the importance of a wellness culture, which led to the addition of formal preintervention CMHC staff wellness training.

Study Rigor and Quality

Our stakeholder co-PI participated in all study team meetings and provided critical input into discussions about barriers and facilitators to model implementation. The study team benefited from further opportunities for robust review and discussion of study methodology and data at the semiannual meetings of the SAB and data safety and monitoring board (DSMB). Members of both boards contributed their time and expertise to monitor study conduct and progress.

Transparency of the Research Process

The study team shared regular updates about the study process and progress with key stakeholders through routine engagement with the SAB and DSMB as well as other methods of stakeholder involvement, such as local, regional, and national presentations and stakeholder forums.

Adoption of Research Evidence Into Practice

The successful engagement of stakeholders both during and after study implementation has led to the successful scaling of behavioral health homes to more than 50 CMHCs across Pennsylvania. State government leaders are highly engaged in the dissemination process and interested in continuing model scaling as a best practice to be adopted by other state-supported behavioral health provider facilities. Our discussions with stakeholder partners also led to an application for additional PCORI funding to disseminate and implement behavioral health homes in diverse settings that serve individuals who have or are at risk for chronic conditions, including adolescents in residential treatment facilities and individuals attending opioid treatment programs.

Methods

Study Design

The University of Pittsburgh IRB reviewed and approved this study. Our team used a cluster randomized design that incorporated a pragmatic, mixed-methods approach for comparing the 2 study interventions. We randomly assigned CMHCs from within the provider network of the Community Care Behavioral Health Organization (Community Care) to either provider-supported or self-directed. Upon notification from PCORI of the award to conduct this research, we worked closely with CMHC leadership to revisit our original participant eligibility estimates using CMHC-level data. Because of this process, we established new and more precise estimates of the number of eligible participants in the study population. Because these estimates were lower than expected, as outlined in the original proposal, we invited 3 additional CMHCs to join the collaboration before randomization on April 29, 2013, increasing the number of participating CMHCs to 11 sites. As a result, we were able to increase the number of eligible individuals with SMI to ensure adequate power for detecting significant differences between the study arms.

We based our cluster randomization scheme on a minimization algorithm that balances on prognostic factors by ranking all individuals who receive services at each participating CMHC by age and SMI diagnosis and then assigning the CMHC to the intervention that minimizes the variability in the sum of the ranks (ie, the imbalance) across both interventions.61 If the 2 interventions are tied on imbalance, the assignment of the CMHC is random. In the final analytic models, we also included age, SMI diagnosis, and other patient- and clinic-level characteristics that may moderate the impact of the study interventions.

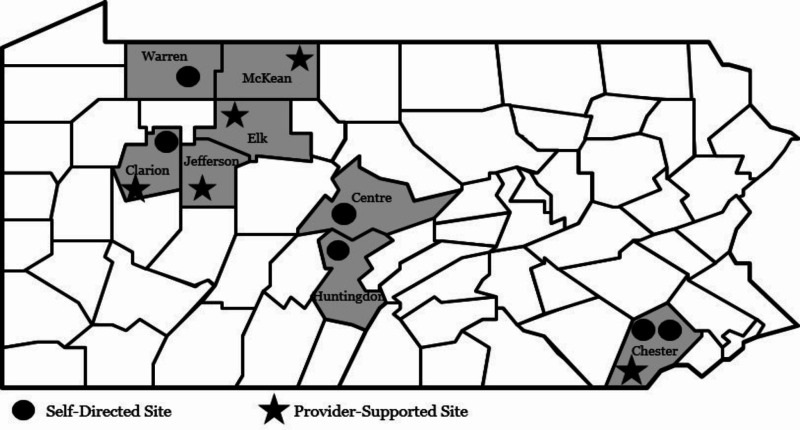

During the randomization process, we also combined 2 smaller sites in the same county with like characteristics and geographic proximity, to have equal numbers of clusters randomized to 1 of the 2 study arms. Figure 1 provides information regarding the location of each participating CMHC.

Figure 1

Location of Participating CMHCs.

Participants

The target population was Medicaid-enrolled adults aged 21 and older with SMI who received services at CMHCs within Community Care's provider network. SMI diagnoses are illnesses that are chronic and can cause substantial functional impairment.62 We determined SMI diagnoses through service user claims data, using claims associated with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression. We did not include anxiety disorders (ie, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder) or eating disorders, which can sometimes fall under the definition of SMI. Because clinicians assess symptom duration and functional impairment as part of the routine diagnostic evaluation of SMI, we did not conduct an additional assessment of these factors on enrollment. We defined receipt of services as having at least 2 claims for outpatient, case management, or peer specialist services during a 6-month period.

As noted in the “Study Design” section, upon receipt of funding in 2012, we reran our eligibility files to ensure that any new potential participants were identified. We made further updates through early 2013 to ensure maximum capture of eligible service users at each site. Individuals who were unable to speak and write in English were deemed ineligible for the study.

We recruited and consented Individuals who met the criteria for our target population during a 4-month continuous enrollment period beginning in month 1 of the project. The research team educated CMHC staff on how to initiate the eligibility screening and consenting procedures for interested service users via an online web portal. Of those eligible service users (N = 1443), 1109 enrolled within the first 3 months of the study. We extended enrollment for the self-directed arm to 6 months, to decrease imbalance in the number of service users recruited into each study arm, to ensure that we had an adequate sample size to address our aims, and to promote racial/ethnic variability in the study sample. Because of this extension, we were able to enroll an additional 120 participants in self-directed sites, resulting in a total of 1229 study participants (provider-supported = 713; self-directed = 516). Due to these variations in enrollment windows, participant follow-up ranged from 18 to 24 months. Of all eligible service users, 72 declined to participate and 142 did not participate for “other” undocumented reasons.

Study Setting

CMHCs are often either the most common or only location in which individuals with SMI seek health-related services. Consequently, they can serve as an ideal location for moving beyond traditional behavioral health service delivery to providing holistic health and wellness care to those at increased risk for chronic physical health conditions. In regions across Pennsylvania, 5 CMHCs implemented provider-supported and 6 CMHCs implemented self-directed (Figure 1).

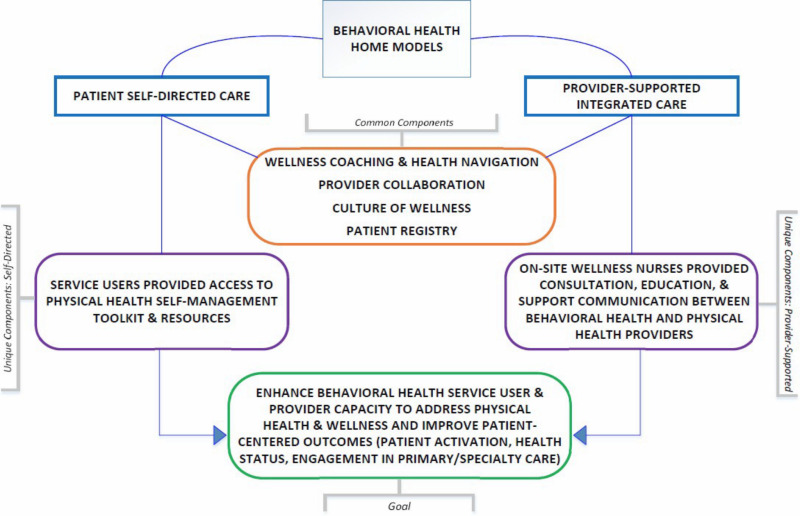

Interventions

As comparators for this study, we chose interventions that have an evidence base39,40,57-60 and the potential to provide a patient-centered option for optimal holistic health and wellness service delivery in CMHCs. Participating sites implemented the interventions not to achieve different outcomes but to provide similar wellness information and support for service users via different methods. Refer to Figure 2 for an overview of the unique and common components of each intervention.

Figure 2

Unique and Common Components of the Behavioral Health Home Models.

Culture of Wellness

Participating sites implemented 1 of the 2 intervention approaches, provider-supported or self-directed, within a culture that promotes a healthy lifestyle, disease prevention, and health education/promotion. Both interventions shared many common components, including training care delivery staff (eg, case managers, wellness nurses, peer specialists) in wellness coaching so they could (1) work with patients in addressing preventable or reversible chronic disease risk factors; (2) enhance staff and patient engagement with primary care physicians; and (3) promote recovery by helping patients achieve physical, emotional, social, and financial wellness.

In the following paragraphs, we describe components specific to provider-supported and self-directed. Overall, provider-supported offered additional assistance via nurses to service users who might otherwise have difficulty accessing care and monitoring physical health. Self-directed honored and encouraged individual autonomy and engagement via a self-management toolkit. Although components of each approach are likely important, stakeholders had limited information about their differential impact on patient-centered outcomes.

Provider-Supported Care

This intervention used a full-time registered nurse on staff at CMHCs to provide consultation to wellness coaches. Nurses were responsible for educating CMHC staff about common medical comorbidities, working with wellness coaches to develop tailored wellness plans, and assisting wellness coaches with patient transitions from inpatient to community-based settings. Nurses assisted patients with coordinating and accessing preventive, primary, and specialty medical services, and with monitoring progress.

Self-directed Care

This intervention incorporated a secure web portal to facilitate access to content tailored to members' needs/goals, inspire individuals to learn about their conditions, and encourage individuals to take an active role in their own health care. The portal contained personal health information, such as medical conditions; service use history specific to primary care; specialty visits and medications; access to self-guided wellness interventions; and trackers for smoking cessation, weight management, nutrition, and sleep hygiene. Patients could access the portal independently or in conjunction with wellness coaches. Sites also provided similar resources for service users in a paper toolkit format.

Intervention Implementation Support

Implementation support strategies were employed across both provider-supported and self-directed sites. These strategies included the following:

Wellness Champions and Intervention Training

To enhance the spread and sustainability of the wellness culture, each organization identified several staff members to serve as “wellness champions” and trainers using a “train-the-trainer” model. Wellness champions promoted intervention initiatives in building a culture of wellness at their agency/location by supporting program goals and providing participants with motivational support and wellness resources.63,64 A portion of the staff was also trained in intervention or program delivery; these staff then used their knowledge and skills to train additional individuals.65

We designed a 4-day (24 hours total) wellness training to improve providers' knowledge, skills, and attitudes about physical and behavioral health conditions while increasing their capacity to engage and communicate with individuals with SMI about health and wellness care in the context of their recovery.66 Curriculum topics included basic education on chronic medical conditions common among individuals with SMI, strategies for enhancing collaborative care, wellness interventions, and the role of motivation in behavior change.

Learning Collaboratives

Based on the Institute for Healthcare Innovation's Breakthrough Series,67 learning collaboratives provided a structured process to support intervention implementation and change in the CMHCs through experience sharing, constant quality improvement, and intervention activity monitoring. The learning collaboratives emphasized group learning through small tests of change and reliance on repeated, minimal data capture to monitor improvements.

Each month, participating providers worked to implement study interventions and then collected and submitted staff survey data to the learning collaborative data team. After collating these data, the data team shared the composite information with providers, who used it to guide rapid improvements in implementation through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) process. The learning collaboratives organized monthly webinars to discuss the data and share new ideas for change and improvement.

The learning collaboratives completed a total of 99 PDSA cycles, with provider agencies each completing 5 to 11 PDSA cycles over 12 months. At final assessment, half of the provider partners rated themselves a 4.5, indicating that practices were moving toward sustainability, and half rated themselves a 5.0, indicating that all project goals were completed and the organizational changes were permanent. Overall, we observed consistent improvements in primary intervention components, including wellness goal development, utilization of self-management tools, reciprocal communication between physical and behavioral health providers, and service user confidence and involvement in working toward improved health and wellness, suggesting successful intervention uptake.

Study Outcomes

We sought to understand how 2 unique methods for delivering integrated care activate individuals with SMI to participate in their physical health and wellness; impact utilization; and change their overall health status, functioning, and quality of life. The study team strived to create a comprehensive set of outcome measures that included traditional quantitative measures and surveys; existing primary and secondary data, such as claims data; and qualitative data, to assist with understanding the facilitators and barriers to intervention implementation and the experiences of CMHC service users and staff. We determined specific study outcomes (Table 1) through the full engagement of stakeholders and service users and a literature review.

Table 1

Study Outcomes, Covariates, and Data Sources.

Follow-up

The study team collected data from several sources over the duration of the study period. Using Community Care's secure data collection portal, we gathered self-report data from participating CMHC service users, who were study participants, at baseline and at 4 additional follow-up time points spanning 18 to 24 months. We also collected physical health, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims data from Community Care and the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. Members of the study team conducted qualitative interviews with CMHC service users and staff at 3 time points—baseline, midintervention implementation, and postintervention implementation—to assess experiences with provider-supported and self-directed over time.

Data Collection and Sources

Quantitative Data

We collected self-report data from consented study participants at 5 time points: baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months. At each time point, the study team provided all participating CMHCs with a list of individuals enrolled in the study so that CMHC staff could make targeted efforts to reach as many participants as possible. Service user participants could complete primary measures both via the web portal or by using paper packets, if preferred. The study team provided CMHC staff with laptops and iPads with Jetpack internet service to meet with participants either at the CMHC or in their homes/communities to complete the self-report measures.

We collected behavioral health, physical health, pharmacy, and administrative claims data from all participants who maintained Medicaid eligibility throughout the study period, to assess 1 primary outcome—engagement in primary/specialty care—and several secondary outcomes. An important advantage to using multiple data sources (self-report and existing claims) is the consistent capture of at least some type of data over time for most participants. That is, claims data were available at time points where self-report data may have been lacking.

The study team documented participants as lost to follow-up when they no longer completed study self-report measures and they no longer were Medicaid eligible, which served as a proxy for claims data availability. We used the threshold criterion of 80% Medicaid coverage in the year before each data collection time point to determine Medicaid eligibility.77

We recorded reasons for loss to follow-up and missing data across the entire study period and took steps to minimize attrition as much as possible. After each self-report data collection time point, participating CMHCs provided a log that reflected reasons for missing self-report data. They reported missing data for each measure at each data collection time point. Some of the reasons for missing self-report data included patient discharge from CMHC services, change of address, incarceration, death, participants declining health, hospitalization, unable to reach, and other. Although this information was useful, because it was based on current available information at each site, CMHC staff found some reasons for missing data to be undetermined and documented them accordingly.

Over the course of the study, no participants asked to withdraw. The study team formally withdrew only participants who died during the study period.

Qualitative Data

The study team conducted 3 sets of telephone interviews at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months with 48 service users across the study sites for a total of 144 interviews. We also conducted telephone interviews with 2 CMHC staff members, either case managers, wellness nurses, or lead navigators at each of the 11 sites at the same 3 time points (baseline, 12 months, 24 months), for a total of 66 interviews. Although we attempted to interview the same 2 staff members at each CMHC across all 3 time points, this was not always possible due to staff turnover. If the same staff member was not available for a follow-up interview, we selected a staff member with the same position instead.

Analytical and Statistical Approaches

For our sample size projections, we assumed 1500 eligible adults with SMI across 11 partnering CMHCs with 80% enrollment (n = 1200) and complete data for 75% of those enrolled for inclusion in the final data set (n = 900), with unequal enrollment projected across arms. For the power calculations, we assumed a 2-sided test of level 0.05 and an intracluster correlation of 0.01. When we compared all individuals across arms, we had 80% power to discern an effect size of 0.33, which is a small to medium effect size, according to Cohen.78,79 That is, we were positioned to discern 33% of a standard deviation difference in means between the 2 arms for primary outcomes that are continuous variables, such as patient activation as measured by the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) and health status as measured by the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12).

For our primary aims, we estimated the minimum distinguishable effect sizes with 80% power. Cohen categorizes small effect sizes to be about 0.2, medium effect sizes to be about 0.5, and large effect sizes to be about 0.8.78,79 Our minimum distinguishable effect sizes of 0.34, 0.38, and 0.53 ranged from small to medium, approximately. Thus, we had good power (80%) to distinguish small effect sizes for the overall sample and small to medium effect sizes for our subgroup of interest: gender. Many cluster randomized clinical trials involving mental health services in general medical settings, such as PROSPECT13,80 IMPACT14,81 and MANAS15,82 have reported similar effect sizes. Typically, effect sizes are small to medium in studies like ours (effect size of 0.34), and our analyses showed sufficient power to detect signals of this magnitude, which, although modest, are clinically meaningful, as documented in the cluster randomized clinical trials mentioned above.

We selected 3 primary patient-centered outcomes: patient activation in care, health status (both physical and mental), and engagement in primary and specialty care. Because all measures of the outcomes are continuous, we determined a t test to be applicable and robust, although we transformed the measure of engagement as needed to achieve normality. For our power analysis, because the sample sizes are fixed, we calculated the minimum clinically distinguishable effect size with 80% power based on a 2-sided, 2-sample t test of level 0.05 adjusted for clustering with an intracluster correlation of 0.01 and adjusted via a design effect for imbalanced cluster size. We utilized the statistical package PASS, which incorporates the intracluster correlation but requires both arms to have the same number of clusters and allows only a single cluster size for the entire study. To be conservative in our calculations, we assumed that both arms had only 5 clusters each and used the smaller average cluster size, which is in arm 2, across the 2 arms.

Quantitative Analysis

Before examining our primary analyses, we conducted descriptive and exploratory analyses to describe the study participants. We also conducted a baseline data analysis to examine the differences between the 2 intervention groups before provider-supported and self-directed were implemented. For continuous variables such as age, we reported the mean, standard deviation, and range. For categorical variables, we reported the percentage of categories. We conducted hypothesis tests of no difference between the 2 intervention groups for each of the baseline characteristics using the analysis of variance F test with generalized linear mixed models (LMMs) accounting for the within-clinic correlation.

For primary aim 1 and secondary aim 1, to compare the effectiveness of the models on our outcomes of interest, we investigated whether the treatment-by-time interaction effect was significant for each outcome. Longitudinal data consist of outcome measurements that are repeatedly collected over time. Such data are collected to address research questions concerned with changes in the mean response or potentially varying mean differences over time, in contrast to cross-sectional data that are concerned with the mean response and mean differences at a single time point. As such, we chose interaction with time to see changes in model effects across time. We examined if the score change from baseline significantly differed between the 2 treatment groups over time after adjusting for covariates. We fit the LMM, including random effects for CMHCs and participants, to control within-clinic and within-participant correlation in the cluster randomized design and included a set of covariates to control confounding effect under a missing-at-random assumption. By including such variables, we were also able to better explain covariate-dependent missingness. In the absence of a significant treatment-by-time interaction effect (significance level of 0.05), we tested marginal treatment and time effects to determine if the score change was significant over time.

To assess the moderating effect of gender (primary aim 2) on our primary outcomes, we explored the 3-way interaction effect (gender-by-treatment-by-time) on each outcome. We did this because the moderating effect on the association between treatment and outcomes can change over time in longitudinally measured data. We used the same LMM described above, with the exception that the regression models included 3-way interaction terms.

For secondary aim 2, we tested the association between engagement in interventions—a 4-level categorical variable based on claims information—and treatment at each time point to measure whether engagement mediated the relationship between treatment and outcomes. In each generalized LMM, we included the same set of covariates to account for potential confounding. We measured the indirect effect of engagement on each outcome by subtracting the residual treatment effect (the treatment-by-time effect adjusting for engagement) from the overall treatment effect (the treatment-by-time effect without adjusting for engagement).

We used the average number of case management, peer services, and psychiatric rehabilitation visits in 6-month intervals as a proxy for overall engagement in interventions. Because all CMHC staff were trained to provide support for positive health choices during all visits, we assumed that participants were likely to engage in elements of wellness coaching during these visits. We were unable to rely on web portal data as another engagement-related metric because some participants in self-directed preferred paper packets to the online interface. Consequently, we could not obtain an accurate web portal/paper packet “dose.”

We conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of attrition across study arms on differences in outcomes, association between CMHCs and being lost to follow-up, and differences in baseline characteristics between participants lost to follow-up vs those who were not. We also examined sensitivity of inferences to the missing-at-random assumption by comparing the demographic characteristics and basic information of participants at baseline between completed cases vs missing cases, and (2) repeating the analysis for primary aim 1 outcomes for completed participants only. We presented the results with and without missing data. We engaged a certified honest broker to link certain data, such as that provided by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services and Community Care administrative/claims. Our statistician was blinded to study arm.

Qualitative Analysis

We followed the editing method outlined by Crabtree and Miller83 to construct the codebooks for the qualitative analysis. Analysts on the study team developed separate codebooks for service user and provider interviews following completion of the first set of interviews. The codebooks were sensitive to comparisons between interventions, capturing themes related to barriers, facilitators, and levels of satisfaction. We captured representative quotations verbatim from the transcripts using Atlas.ti 7. As part of the coding process, analysts met regularly to process any differences in the assessment of codes for each case until agreement was achieved. Through this agreement process, they determined the codes to be recorded for use in the final analysis.

Conduct of the Study

In describing our methods, we have provided information that reflects our executed study protocol. Since the start of the study, we have made several protocol modifications to our PCORI contract. To increase the overall number of eligible participants and enhance the racial diversity of the study sample, we added 3 sites to the originally proposed 8-site cluster randomized trial. Additionally, we modified or dropped several study measures that were viewed as repetitive or burdensome. Due to the overestimation of our eligible target population, we reduced our sample size from 2248 to 1229. Because of this reduction, we were no longer able to examine the moderating effect of several participant characteristics on primary outcomes and could examine the moderating role of gender only as part of our subgroup analysis. Finally, PCORI approved our request to extend our contract for an additional 9 months so that we could gather all of the secondary claims data needed to complete our analyses for the claims-based outcomes. The Pittsburgh IRB and our study DSMB reviewed and approved these modifications.

Results

In this section, we present our mixed-methods study results. First, we provide our quantitative results, which include descriptive statistics related to patient characteristics for each intervention arm. Then we share findings from the analysis of our 2 primary aims, followed by the results of the analysis of our 2 secondary aims. Finally, we provide results from our qualitative interviews with service users and CMHC staff.

Quantitative Results

Participant Characteristics

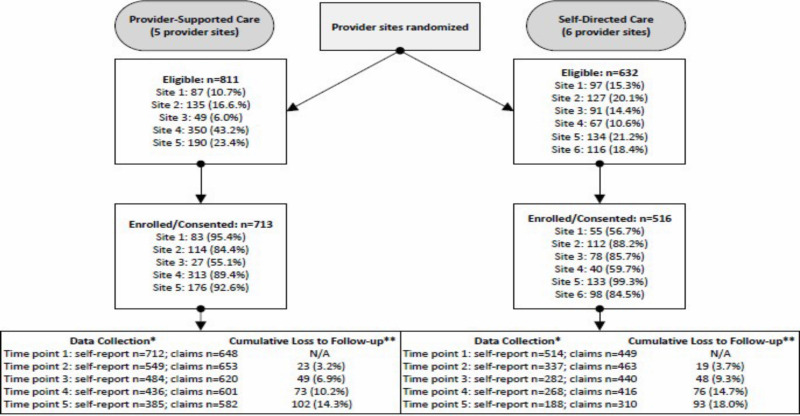

We consented and enrolled a total of 1229 adults with SMI in this study, including men (37%) and women (63%), with 713 in provider-supported and 516 in self-directed. Participants had a mean age of 43 years, and most were White (90%). Refer to Table 2 for information about our study sample characteristics; Table 3 for patient population, intervention or issue, comparison with another intervention or issue, and outcome and time frame (PICOT) descriptors; and Figure 3 for our study flow diagram.

Table 2

Study Sample Characteristics by Intervention Arm.

Table 3

PICOT Descriptors.

Figure 3

Study Flow Diagram.

Participant Attrition

The number of service users who completed self-report measures decreased at each time point. For provider-supported, n = 712 completed self-report measures at baseline (1 participant did not complete self-report measures at baseline) and n = 385 completed the measures at the final time point. For self-directed, n = 514 completed self-report measures at baseline (2 service users who consented did not complete self-report measures at baseline) and n = 220 completed the measures at the final time point (the final time point varied for self-directed, with some completing 5 data collection time points and others completing 4 due to late enrollment). Overall, self-report loss to follow-up was n = 327 in provider-supported and n = 294 in self-directed. Even if we were unable to obtain self-report data from participants at each time point, we were still able to observe claims data associated with 1 primary and several secondary outcomes for all participants who maintained Medicaid eligibility. We considered individuals entirely lost to follow-up only if they did not complete any more self-report measures AND if they never regained Medicaid eligibility.

Loss to Follow-up Sensitivity Analysis

Based on the results from our sensitivity analysis of missing data, we observed no statistically significant difference between arms for the number of participants who were lost to follow-up (P = .078). We also found no evidence to conclude that individual CMHC sites were associated with loss to follow-up (P = .36).

Regardless of treatment group, participants who remained in the study tended to be older (P = .031), had a different diagnosis at baseline (P = .005), and were more likely to have 80% Medicaid eligibility (P < .001) in the year prior than those who were lost to follow-up. At baseline, participants in provider-supported had less severe SMI (P = .004) and were more likely to have Medicaid eligibility (P < .001) if they remained in the study. In self-directed, retained participants were older (P < .001), differed in their baseline diagnosis (P = .01), and were more likely to have Medicaid eligibility (P = .043). Because we included each of these variables as covariates in our mixed models, we did not have to meet the missing-at-random assumption for them.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine if our missing-at-random assumption was violated by conducting the time-by-treatment interaction test for primary aim 1, both with and without missing cases. The only outcome with a significant treatment-by-time interaction effect was patient activation, and the results of this test were the same both with and without missing cases.

Primary Outcomes

When reporting results for our 3 primary outcomes, we include treatment-by-time interaction assessing whether the outcomes changed over time and differed in this change for each intervention arm. If we did not observe a treatment-by-time interaction, we assessed main effects to determine if a significant change in outcomes occurred from baseline. In addition, we conducted a subgroup assessment to determine whether outcomes for men and women differed by intervention arm.

Primary aim 1

For our first primary aim, we compared the effectiveness of provider-supported and self-directed on 3 primary patient-centered outcomes: patient activation, health status, and engagement in primary/specialty care. For this study, we considered health status to be a single primary outcome. However, because we used the SF-12 to measure this outcome, and this measure utilizes both a physical health and mental health subscale, we report findings from each subscale separately.

In this section, we provide basic information tables with score or outcome change over time for each arm and the number of participants analyzed at each time point. We also include significance values for our interaction test, the F value, and the intracluster correlations for both clinics and participants. In the absence of a significant treatment-by-time interaction, we report marginal effects of treatment and time in tabular format. For our primary outcomes, we also include a figure that highlights the trajectory of outcome change over time and confidence interval.

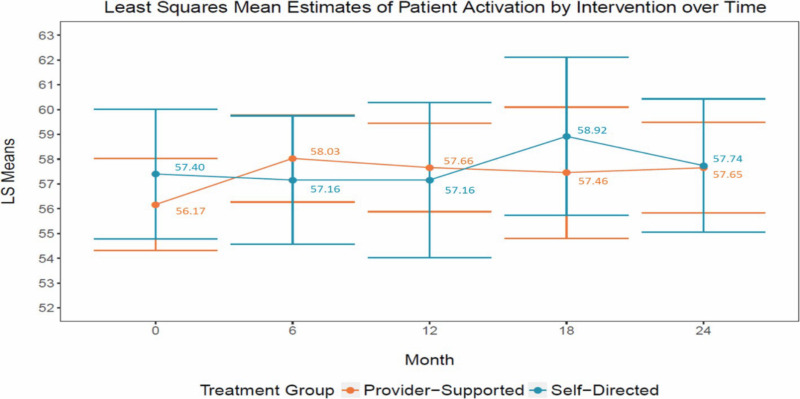

Table 4 shows the interaction effects for patient activation; scores range from 0 to 100, with the higher score indicating higher activation. After covariate adjustment, we observed a significant difference between the 2 arms at data collection time points for PAM score (P < .0001). PAM score differed the most between provider-supported and self-directed at 6 months after the start of the interventions, with provider-supported experiencing a sharper increase and self-directed not experiencing a score increase until months 12 to 18 (Figure 4).

Table 4

Patient Activation Interaction Effect (Self-report Measure).

Figure 4

Visual of the Impact of Interventions on Patient Activation.

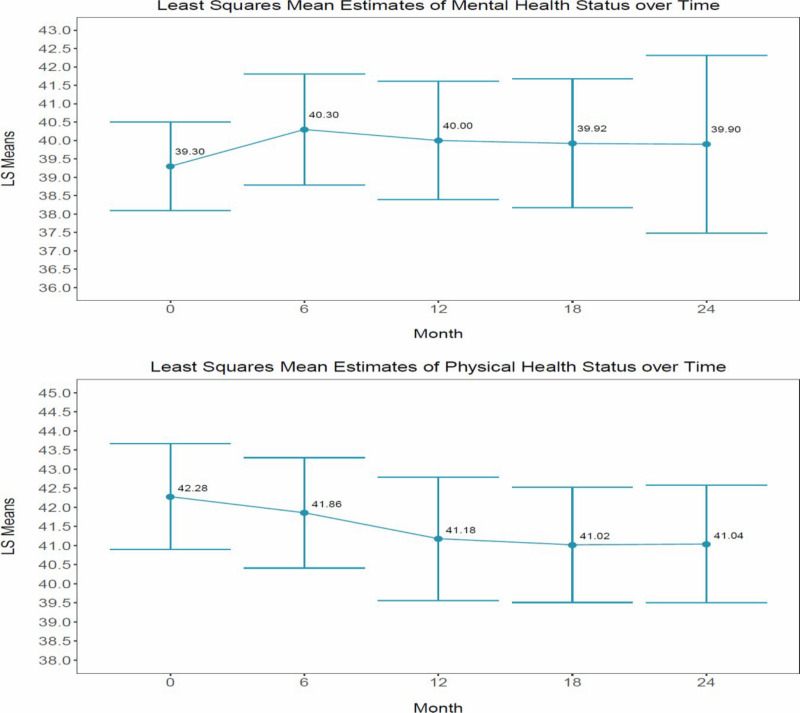

In Table 5, we present the results from our test of the mental and physical health status interaction effect. Change in physical health status and mental health status, as measured by the Health Survey Short-Form, did not result in a significant treatment-by-time interaction for either subscale (mental health: P = .2179; physical health: P = .4103). SF-12v2 scores range from 0 to 100, where 100 equals the highest level of health. However, both composite scores did change significantly over time for both study arms (mental health: P < .0001; physical health: P < .0001). Interestingly, perceived mental health status improved over time, although perceived physical health status did not. See Table 6 for marginal time effects and Figure 5 for a visual of perceived change in mental and physical health status over time.

Table 5

Mental and Physical Health Status Interaction Effects (Self-report Data).

Table 6

Mental and Physical Health Status Marginal Time and Treatment Effects (Self-report Data).

Figure 5

Visual of the Change in Mental and Physical Health Status Over Time.

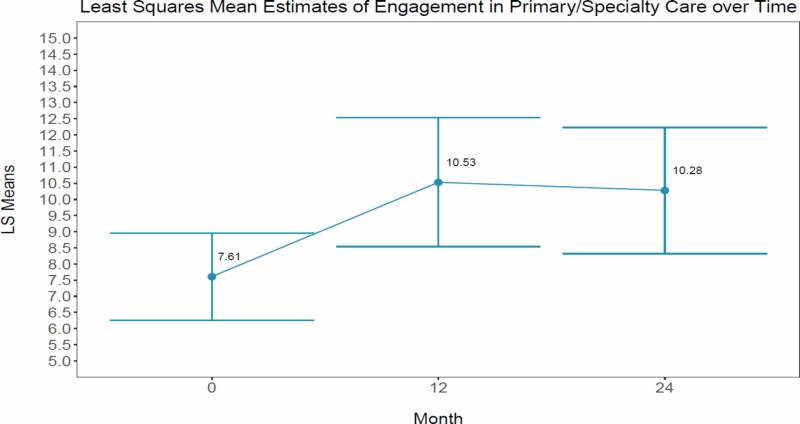

We observed no significant difference between study arms over time for engagement in primary/specialty care (P = .1645); however, this outcome increased significantly for both provider-supported and self-directed over time (P = .0157). See Table 7 for interaction effects; Table 8 for marginal time effects; and Figure 6 for a visual of the change in primary/specialty care over time.

Table 7

Engagement in Primary/Specialty Care Interaction Effect (Claims Data).

Table 8

Engagement in Primary/Specialty Care Marginal Time and Treatment Effects (Claims Data).

Figure 6

Visual of the Change in Primary/Specialty Care Over Time.

Primary aim 2

In Tables 9 to 13 we present data that correspond to primary aim 2. To address our second primary aim, we examined whether gender influenced the strength of, or moderated, the impact of the interventions on our 3 primary outcomes. We first report 3-way interaction effects. We report treatment-by-gender interaction effects in the absence of a significant 3-way interaction effect, assuming that the moderating effect of gender does not depend on time.

Patient activation score assessment revealed a significant 3-way interaction effect of gender-by-treatment-by-time (P = .0019). Women showed greater improvement in patient activation at 6 months (approximately a 3-point increase) in provider-supported; men only nominally improved in patient activation over time in this same study arm. Men's average patient activation score increased more than women's in self-directed (also nearly a 3-point increase). However, score improvement was slower and it peaked at 18 months (Table 9).

Table 9

Interaction Effects Assessing the Moderating Role of Gender on Patient Activation (Self-report Data).

For the SF-12v2 mental health subscale, we fit the main effect model due to the absence of the treatment-by-time interaction effect (Table 10) and found a significant treatment-by-gender effect (P = .0014; Table 11). Women had higher mental health scores in self-directed than women in provider-supported. Men had higher mental health scores in provider-supported than men in self-directed. Overall, we observed higher mental health status scores for men than for women in both intervention arms. We found no gender-by-treatment interaction effect for physical health status (P = .4068).

Table 10

Interaction Effects of the Moderating Role of Gender on Mental and Physical Health Status (Self-report Data).

Table 11

Gender by Treatment Effects for Mental and Physical Health Status (Self-report Data).

In Table 12, we report nonsignificant results from our gender-by-treatment-by-time interaction test. We also found a subsequent analysis of a gender-by-treatment interaction to be nonsignificant (Table 13).

Table 12

Interaction Effects Assessing the Moderating Role of Gender on Engagement in Primary/Specialty Care (Claims Data).

Table 13

Gender by Treatment Effects for Engagement in Primary/Specialty Care (Claims Data).

Secondary outcomes

We assessed several secondary outcomes based on self-report data, including hope, quality of life, functional status, and patient satisfaction with care. In addition, we analyzed the impact of provider-supported and self-directed on several claims-based outcomes, including medication adherence, emergency department utilization, and laboratory monitoring.

Secondary aim 1

In Tables 14 to 17 we provide information about the findings assessed in secondary aim 1, including the impact of the interventions on our secondary outcomes, namely mental health symptoms, hope (scores range from 1 to 10, with 10 being filled with hope), quality of life (scores range from 14 to 70; higher scores indicate better enjoyment and satisfaction with life), medication adherence, functional status (scores range from 0 to 30; higher scores indicate higher impairment), emergent care, laboratory monitoring, and satisfaction with care (each of the 20 items' response options range from 1 to 5; overall score is the average score across all 20 items; a higher score indicates higher satisfaction). We found significant treatment-by-time interaction effects for some self-report outcomes, including hope (P = .0058), quality of life (P = .0014), and patient satisfaction with care (P = .0021; Table 14).

Table 14

Interaction Effects for Self-report Secondary Outcome Measures.

Claims-based secondary outcomes with significant treatment-by-time effects included medication adherence for diabetes medications (P < .0001); emergent care use (P = .0020); and laboratory monitoring for total services (P = .0029), glucose (P < .0001), and lipids (P = .0202; Table 15). The absence of a treatment-by-time interaction effect led to the assessment of change in the remaining outcomes over time, which was significant for functional status (Table 16), medication adherence for hypertension, and lipid laboratory monitoring (Table 17). We observed no significant findings for antipsychotic medication adherence or EKG laboratory monitoring.

Table 15

Interaction Effects for Claims-based Secondary Outcome Measures.

Table 16

Marginal Time and Treatment Effects for Self-report Secondary Outcome Measures.

Table 17

Marginal Time and Treatment Effects for Claims-based Secondary Outcome Measures.

Secondary aim 2

For secondary aim 2, we sought to understand whether engagement in the interventions (high, medium, low, and no engagement) mediated, or explained, the relationship between the interventions and our primary and secondary outcomes. We used the average number of case management, peer services, and psychiatric rehabilitation visits in 6-month intervals as a proxy for engagement in the interventions. We assumed that participants were likely to engage in some element of wellness coaching during these visits because all staff were trained in model implementation and encouraged to engage service users in health and wellness during all visits.

Based on the association analysis between engagement and treatment at each time point, we found no evidence to suggest that the degree of engagement calculated by our proxy measure affected outcomes. Therefore, we cannot claim that our engagement in interventions variable satisfies the sufficient and necessary condition to be a mediator.

Qualitative Findings

We conducted a total of 144 service user interviews and 66 CMHC provider interviews at 3 time points over the 2-year implementation period (baseline, midpoint, and completion). See Table 18 for qualitative themes and illustrative quotes.

Table 18

Qualitative Themes and Illustrative Quotes.

Intervention Satisfaction

Based on our analysis of the qualitative interviews, we found few differences related to experiences and satisfaction between intervention arms. From baseline to the completion of the 2-year active intervention period, service users' definition of health and wellness shifted from vague and impersonal to more detailed/specific, and their recognition of the interconnection between health and wellness increased. Most service user participants had positive intervention experiences, and many developed wellness goals.

Intervention Engagement

Many service users stated that their relationship with CMHC wellness coaches was a leading contributor to intervention participation. Wellness coaches who invested time, showed compassion, suggested specific tools and resources to achieve wellness goals, kept service users on track and motivated them to make positive lifestyle changes, and revealed their own health habits and struggles were more likely to effectively engage service users in wellness-related goal setting and activities.

Positive Impact of Wellness Coaching

Both service users and providers reflected on the positive impact that wellness coaching had on several chronic disease risk behaviors, including the following:

- Smoking cessation: “He went from 3 packs a week to 1 pack a month, and he did that within 6 months.”

- Weight loss: “I've actually exceeded my goal The weight I am now, I haven't been since I was a young teenager I lost 25 pounds in the beginning and I've actually lost closer to 45. I feel like I have more energy.”

- Improved diet: “I am eating a lot more fruits and vegetables trying to watch my calories. My case manager knows that I just started watching my calories and she'll ask me how the calorie counting is going. She encourages me.”

- Increased exercise: “I try to get out every day. I make it a point to get out and walk.”

Agency Support

Providers, namely case managers, wellness nurses, and lead navigators, described a high degree of agency support for the implementation of wellness coaching and wellness culture development. The majority believed that the interventions had a positive impact on service user health and wellness. All interviewees stated that their CMHC had already integrated the behavioral health home model components into routine practice and fully intended to continue the interventions after the completion of the study. Service users were not the only individuals who benefited from the interventions. Many providers revealed that they also developed a wellness goal because, as 1 provider stated, “If we don't do it ourselves, how can we promote it with our clients?”

Barriers to Engaging Service Users in Interventions

CMHC providers identified several barriers to engaging service users in wellness coaching. They mentioned structural barriers, such as lack of access to health care, lack of community resources, and transportation issues, as potential limiters of success. Providers also found it challenging to engage some service users in wellness coaching due to the severity of their mental illness or other more immediate issues, such as housing instability. In addition, some providers were concerned about service users who had been successful with wellness goal achievement, fearing they would “relapse” to their previous unhealthy behaviors once discharged from CMHC services.

Discussion

Decisional Context

We designed this comparative effectiveness study to understand how 2 methods of delivering integrated care for adults with SMI, provider-supported and self-directed, affect important patient-centered outcomes. We also sought to provide more information about which method should be adopted by CMHCs, or if the methods generally lead to similar outcomes. Our findings demonstrate that behavioral health providers can successfully integrate physical health and wellness support in existing care delivery settings to affect outcomes that are most important for service users, specifically patient activation, use of primary care, and unplanned care.

We observed a significant difference in several outcomes in provider-supported and self-directed at varying data collection time points; however, we ultimately observed similar changes in outcomes in both intervention arms. This finding suggests that, although the availability of a wellness nurse may have helped support faster activation in care, embedding health navigation into the case manager role may be a key element leading to successful and similar outcomes in both arms.

Our lack of opportunity to conduct heterogeneity of treatment effect analyses beyond gender limits our ability to suggest 1 intervention over the other for populations that vary by other important moderating variables. Nevertheless, our findings and the associated resources produced through this work will be helpful to systems (payers and providers) that wish to support the comprehensive, whole health of individuals who have or are at risk for chronic conditions.

Our implementation manual and resources provide organizations with increased capacity to help service users enhance their engagement in routine, preventive care and assist them in identifying and addressing wellness and physical health challenges using self-management tools and techniques. This person-centered model of care allows behavioral health providers to address physical health and wellness with the same competence used to influence behavioral health and other psychosocial and resiliency goals.

Staff members take part in wellness coaching training.66,84 Then, with the support of the learning collaborative process, they integrate “Health Navigation” into their daily work, identifying and addressing health risk factors using resources outlined in the Behavioral Health Home Plus intervention manual and toolkits. The wellness planning process promotes regular discussions between health coaches and service users to explore service user strengths, values, and wellness domains that are important to them. This process leads to the development of specific wellness goals that service users work to achieve with the continued support of their wellness coach.

Study Results in Context

Our Findings in Context

Intervention resources provide an avenue for service users to increase their knowledge about how to make behavior changes that can lead to the prevention and/or management of chronic conditions, understand the interconnection of physical health and behavioral health and how one can positively or negatively affect the other, and improve health literacy and communication skills with providers.

A systematic review of lifestyle interventions aimed at improving health behaviors and outcomes for individuals with SMI found promising results and supports the notion that integrating health and wellness into routine care delivery for this population can serve as a method to help reduce early morbidity and mortality.85 In our study, service users worked collaboratively with wellness coaches to identify and take small incremental steps toward achieving their wellness goals, a finding supported by prior research showing that peer specialists and health navigators can be trained to provide effective self-management.36

Service users also consulted with on-site wellness nurses, who provide them with important information about their vital signs, laboratory results, and medications and make appropriate referrals to other behavioral and/or physical health providers as required. In an evaluation of a nurse care management program similar to this study's provider-supported intervention arm, researchers found improvements in patients' chronic diseases and mental illness when compared with usual care.36

The uptake and use of the interventions by behavioral health organizations can result in important changes for the individuals they serve. When service users receive their care at provider organizations that have committed to a culture of wellness, have trained their staff in wellness principles and tactics, use resources and materials to support holistic care delivery, and engage in learning collaborative implementation to support the overall change, patient-centered outcomes are positively affected.

We found a nearly 2-point increase (1.86-point increase in provider-supported at 6 months and 1.76-point increase in self-directed at 18 months; mean baseline score was 56.76 and 56.99 for provider-supported and self-directed, respectively) in patient activation in scoring that ranges from 0 to 100 and a 35% total increase in primary/specialty care use. Both results reflect meaningful and relevant changes. Research shows that when activation levels change, health outcomes tend to change in the same direction, and more efficient use of care follows.86,87 For example, a single-point increase in PAM score correlates to a 2% decrease in hospitalization and a 2% increase in medication adherence.88,89 Given that patient activation is an important and modifiable factor for influencing both physical and mental health outcomes, health care delivery systems can use this information to personalize and improve care.90,91 Moreover, high rates of primary care use for those with behavioral health conditions lead to higher receipt of preventive measures outlined in clinical practice guidelines (eg, colonoscopy, HbA1c and lipid tests, blood pressure) and significantly greater improvement in physical health.38,92

In our analysis of the moderating role of gender, patient activation scores increased by nearly 3 points for women in provider-supported (2.82) and for men in self-directed (2.79). The Living Well intervention, a disease self-management education program aimed at improving outcomes for individuals with SMI, found a clinically meaningful change associated with a 3- to 3.5-point increase in patient activation score.91 Our analysis of gender found similar, although slightly smaller, improvements in patient activation among our study population.

Longitudinal findings show that patient activation in provider-supported improved early in intervention implementation and remained stable over the 2-year implementation period. In self-directed, patient activation slowly declined, suggesting that the availability of and interaction with the wellness nurse may have promoted sustained activation.

Mental health status and engagement in primary care increased and remained stable for both intervention arms; however, physical health status slowly declined over time. Our stakeholder co-PI and other collaborators believe that the slow decrease in perceived physical health as measured by the SF-12 is likely because of increased awareness of physical health diagnoses and challenges related to increased outpatient utilization and engagement in wellness coaching. Due to our limited 2-year implementation period, we were unable to observe if perceptions of physical health status level off over time and perhaps increase once individuals achieve their wellness goals and become better at managing their physical health conditions.

Diagnostic Considerations

The disparity in rates of major depressive disorder (MDD) between the 2 study arms should be considered. A substantial body of work has focused on the use of self-management strategies related to improving overall health, grounded in brief behavioral approaches to major depression. This literature addresses learning-based psychotherapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy, problem Sosving therapy, and behavioral activation, that have both treatment and preventive efficacy for major depression.

Because this literature supports a “goodness of fit” for self-directed, with an emphasis on the use of tools or strategies to support healthy choices in persons living with MDD, the disparity in MDD rates between the 2 arms may work to the study's advantage. However, this disparity also poses a greater challenge to demonstrating the value of provider-supported vs self-directed. Nevertheless, we were able to demonstrate this value (treatment-by-time interactions) in several primary and secondary outcome measures that showed greater and earlier improvement for participants in provider-supported, despite the better fit of self-directed with MDD.

Learning Collaborative Efforts

The past experiences of the Community Care Behavioral Health Organization with engaging provider organizations in strong and meaningful collaboration has been integral to intervention success. The learning collaborative served as a critical component for promoting buy-in and implementation ownership at provider organizations. Our learning collaborative findings suggest successful intervention uptake as observed by participation rates, goals achieved, and consistent improvements in primary intervention components. With this important information about best practices for engaging both providers and behavioral health service users in addressing physical health and wellness through behavioral health settings, our results point to additional opportunities for implementing behavioral health homes in environments that serve those with complex physical and behavioral health conditions and needs.

Implementation of Study Results

Behavioral Health Home Plus

Given the real-world implementation of this study, participating CMHCs have already fully integrated the interventions at their sites. Based on the success of both provider-supported and self-directed in improving outcomes, albeit at different time points, Community Care has developed the Behavioral Health Home Plus (BHHP) model. This model combines the primary elements of provider-supported (wellness nurse) and self-directed (self-management toolkits) to optimize intervention impact.

Members of the study team, along with other Community Care staff, have developed a comprehensive implementation manual for bringing the model to scale at additional CMHCs, with more than 50 sites currently implementing BHHP across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. We have also tailored the BHHP manual to support model uptake in treatment facilities that serve adolescents in both schools and community-based treatment programs. In addition, we plan to utilize learning collaboratives to support additional dissemination and implementation efforts in youth behavioral health residential treatment facilities and opioid treatment programs to ensure that other high-risk, high-need populations can experience improvements to their health, wellness, and quality of life.

Dissemination of Information Regarding Implementation Facilitators and Barriers

We experienced challenges during study implementation that resulted in valuable lessons learned, particularly regarding introducing a transformative model of care that may differ from the day-to-day flow of activities in real-world settings. Using the learning collaborative model, each participating CMHC identified 3 to 4 implementation champions who participated in all learning collaborative sessions and brought information and excitement back to their respective facilities to improve and promote model adoption. In addition, using Plan Do Study Act cycles and sharing implementation facilitators among those participating in the learning collaboratives allowed sites to determine how to best integrate behavioral health home components into routine practice.93 Staff turnover was also common among CMHC staff, but the use of the train-the-trainer model allowed for easy onboarding of new staff, reducing the risk of lapses in intervention delivery. We published a detailed account of our implementation experiences to serve as a resource guide for others who wish to implement similar models or studies.94

Generalizability

The findings from this study provide important information about best practices for engaging adults with SMI in addressing physical health and wellness. The Medicaid status of those enrolled indicates that our participants are low income, which introduces additional financial and social-structural burdens that may create challenges to leading a healthful life.