This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

Continuing Education Activity

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is an inflammatory condition affecting the juxtalimbal cornea. The pathophysiology involves a complex interplay between host autoimmunity, the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral cornea, and environmental influences. The underlying cause may be local or systemic, infectious or noninfectious. Progressive stromal lysis can cause corneal perforation, which is an emergency. PUK occurring in patients with an underlying autoimmune disease carries significant morbidity and mortality.

Management for PUK includes aggressive topical corticosteroid therapy to reduce inflammation and prevent corneal perforation, alongside the use of antibiotics for secondary infections. Systemic immunosuppressants may also be considered in cases associated with systemic diseases.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance learners' proficiency in evaluating and managing PUK. Participants gain a broader grasp of the condition's risk factors, pathogenesis, symptomatology, and best diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Greater competence enables clinicians to work within an interprofessional team caring for patients with PUK.

Objectives:

- Identify the clinical features indicative of peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

- Develop clinically guided diagnostic approaches for peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

- Implement individualized, evidence-based management plans for peripheral ulcerative keratitis cases.

- Collaborate with the interprofessional team to educate, treat, and monitor patients with peripheral ulcerative keratitis to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a disorder affecting the juxtalimbal cornea, classically presenting with epithelial defects and stromal lysis. This rare but severe inflammatory condition results from a complex interplay between host autoimmunity, the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral cornea, and environmental factors. The underlying cause could be local or systemic, infectious or noninfectious. PUK may be due to vasculitides or collagen vascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can account for up to 53% of PUK cases.[1] PUK with scleritis has a poor prognosis. Progressive stromal lysis can cause corneal perforation and, in patients with an underlying autoimmune disease, carries significant morbidity and mortality.

PUK without systemic association is known as Mooren ulcer (MU) and comprises 31.5% of PUK cases.[2] Bowman first described this condition in 1849, followed by McKenzie in 1854, who called it an "ulcus roden" of the cornea.[3] Mooren ulcer occurs in the absence of scleritis and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinical signs begin in the peripheral cornea and progress centrally and circumferentially, with a distinctive overhanging edge.

Quick recognition of PUK is crucial, as it can be the first presenting feature of a life-threatening systemic disease. Meticulous clinical investigation and interprofessional management are required to ensure safe patient outcomes.[4]

The cornea has several layers, including the epithelium, Bowman membrane, stroma, Descemet membrane, and endothelium. The peripheral cornea has a rich vascular supply and an abundance of immune cells, making it more vulnerable to immune-mediated damage and inflammatory disorders like PUK.[5] Most PUK cases arise in the setting of an autoimmune disorder. However, PUK may also result from infections, including herpes simplex virus and bacterial keratitis, ocular surface disorders, trauma, or surgical procedures. The natural history of PUK involves progression from peripheral corneal inflammation and thinning to ulceration, which can lead to perforation if left untreated.[6] PUK may be staged based on the severity of corneal involvement. Without appropriate management, PUK can cause severe complications and may persist for months or even years with periods of remission and exacerbation.[7]

The pattern of spread in PUK usually involves local extension along the peripheral cornea, with the potential for centripetal spread toward the central cornea in severe cases. PUK often presents unilaterally, and bilateral involvement is associated with systemic autoimmune disease. Investigations for PUK include slit-lamp examination with fluorescein staining to evaluate epithelial defects, microbial cultures to rule out infections, and testing for systemic autoimmune markers like antinuclear antibodies (ANA), rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Anterior segment optical coherence tomography may also be used to assess corneal thickness.[8]

Management of PUK involves both medical and surgical approaches. Topical steroids and immunomodulatory agents, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, control local inflammation, while systemic immunosuppressants, including methotrexate and biologics, are required for treating underlying autoimmune conditions. Surgical interventions, such as amniotic membrane transplantation and corneal transplantation, may be necessary in cases of severe corneal damage or perforation. Referral to a rheumatologist for managing associated systemic diseases is essential to ensure long-term control and prevent recurrence.

The prognosis for PUK varies with severity and the timeliness of treatment. If detected early and treated aggressively, patients can have a favorable outcome and preserve vision. However, delayed treatment may result in corneal perforation, permanent vision loss, and secondary infections.[9]

Etiology

Table 1 summarizes the variety of ocular (local) and systemic disorders that can lead to PUK. Almost half of all noninfectious cases of PUK are associated with a connective tissue disorder, of which rheumatoid arthritis is the most common. PUK affects both eyes in nearly half of all late-stage rheumatoid arthritis cases. Tauber et al report that 34% of eyes with noninfectious PUK have an associated rheumatoid arthritis.[10] PUK is also a relatively common presenting feature of GPA, a systemic vasculitis that affects the sinuses, nose, throat, lungs, and kidneys. GPA-associated PUK is due to a necrotizing vasculitis affecting the anterior ciliary or perilimbal arteries.

PUK manifests with crescentic stromal thinning, inflammatory cells in the juxtalimbal cornea, and an epithelial defect. Infections can involve the peripheral cornea without resulting in PUK. However, infection constitutes 19.7% of all PUK cases and must be ruled out when the ocular disorder is identified. Various microorganisms may cause PUK, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and Acanthamoeba spp.

Mooren Ulcer

This condition is a diagnosis of exclusion and is often accompanied by severe pain.[11] Complications such as anterior uveitis, secondary infection, cataract, glaucoma, and corneal perforation may develop in 35% to 40% of patients. Watson and colleagues have described 3 clinical subtypes.[12]

Type 1 - Unilateral Mooren Ulceration

- Unilateral

- Older than 60 years

- Female patients

- Severe pain

- Rapid progression

- Poor prognosis, recurrence

- Complications rare

Type 2 - Bilateral Aggressive Mooren Ulcer

- Bilateral

- Young (14-40 years)

- Male patients

- Mild-to-moderate pain

- Slow progression but aggressive initially

- Poor prognosis, recurrence

- Complications common

Type 3 - Bilateral Indolent Mooren Ulcer

- Bilateral

- Middle-aged (mid-50s)

- No gender predilection

- Mild pain

- Slow progression

- Better prognosis, recurrence rare

- Complications rare

Epidemiology

In the United Kingdom, estimates for PUK incidence range from 0.2 to 3 patients per million annually.[13][14][15] Female individuals are more likely to be affected generally, although this trend is reversed for Mooren ulcers.[16] Evidence does not support a racial or ethnic predilection for PUK, and the associated cause influences both the likelihood and the age at the initial presentation. Classification is generally clinical, enabling healthcare practitioners to choose appropriate investigations and treatments that target the underlying etiology.

- Incidence and prevalence: PUK is considered a rare condition globally, affecting fewer than 5 individuals per 100,000 annually. PUK is most commonly seen in association with systemic autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or systemic vasculitis.[17]

- Sex distribution: Studies indicate a slight female predominance, particularly in cases linked to autoimmune conditions. This trend reflects the higher prevalence of autoimmunity in women.[18]

- Age groups: PUK primarily affects middle-aged and older adults, especially those in their 6th and 7th decade. However, PUK can occur in younger individuals if associated with autoimmune diseases.[19]

- Global distribution: The condition is reported worldwide, with higher frequencies in populations with higher rates of autoimmune disorders. In developing regions, infectious causes, such as bacterial or fungal keratitis, may be more common triggers for PUK than autoimmune disorders.[20]

Understanding the epidemiology helps identify at-risk populations and target preventative or early intervention strategies.

Pathophysiology

Several significant differences between the central and peripheral cornea make it susceptible to inflammation, ulceration, and furrowing. The peripheral cornea is the transition zone between the cornea, conjunctiva, episclera, and sclera, with a combination of histologic features.[21] Neural innervation and sensitivity are reduced in the peripheral compared with the central cornea.[22] The thickness of the peripheral cornea is around 1000 μm, which is greater than that of the central cornea, which is 550 μm. Epithelial cells adhere more tightly to the corneal basement membrane and stroma in the periphery than in other areas.[23]

The reservoir of corneal epithelial stem cells and the mitogenic activity of corneal endothelial cells are also highest in the peripheral cornea. An imbalance between collagenase and tissue inhibitor activity has been hypothesized to cause the loss of corneal integrity and increased corneal matrix turnover. Elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases, which degrade the extracellular matrix, along with reduced tissue metalloproteinase inhibitors, can result in increased keratolysis.[24][25]

The central cornea is avascular and derives most of its nutrition through the tear film and aqueous humor. In contrast, the peripheral cornea has a well-developed vascular and lymphatic supply, with perilimbal vessels extending 0.5 mm into the cornea. This area is a source of immunoglobulins, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and other immune cells that mediate the inflammatory process.[26]

A combination of humoral and cellular immune mechanisms is often involved in PUK's pathogenesis. In PUK secondary to rheumatoid arthritis, autoantibodies and self-antigens combine to form immune complexes, which activate B cells and complement proteins. B cells can further stimulate T cells to secrete cytokines associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The combination of angiogenesis and immune cell clusters contributes to pannus formation in PUK.[27]

Histopathology

Histopathology is vital in diagnosing PUK and understanding its underlying causes. The key findings of microscopic tissue examination are:

- Inflammatory cell infiltration: Dense infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is often observed in the corneal stroma, particularly in autoimmune-related PUK cases. This inflammation leads to tissue destruction and corneal thinning.

- Necrosis and stromal loss: Severe corneal epithelium and stroma necrosis are hallmarks of active PUK. Necrotic tissue may be observed, especially at the periphery of the cornea.[28]

- Immune complex deposition: In systemic autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, evidence of immune complex deposition (immunoglobulins G and M and complement components) may be seen along the corneal blood vessels. Immune complex deposition contributes to inflammation.[29]

- Angiogenesis: In longstanding cases, neovascularization may be observed within the peripheral cornea. This feature is a sign of chronic inflammation and healing attempts.[30]

Histopathological findings help confirm the diagnosis and differentiate PUK from other causes of peripheral corneal thinning, guiding targeted treatment strategies.

History and Physical

PUK is more often unilateral than bilateral at the initial presentation. Bilateral PUK is often asymmetrical and is associated with systemic disease. Patients typically complain of ocular pain, photophobia, and tearing. The eyes are injected and appear red. Pain is variable but comprises an important feature of PUK. In Mooren ulcers, the pain is often out of proportion to the clinical signs. Reduction in vision is due to inflammation and may be mild or severe.

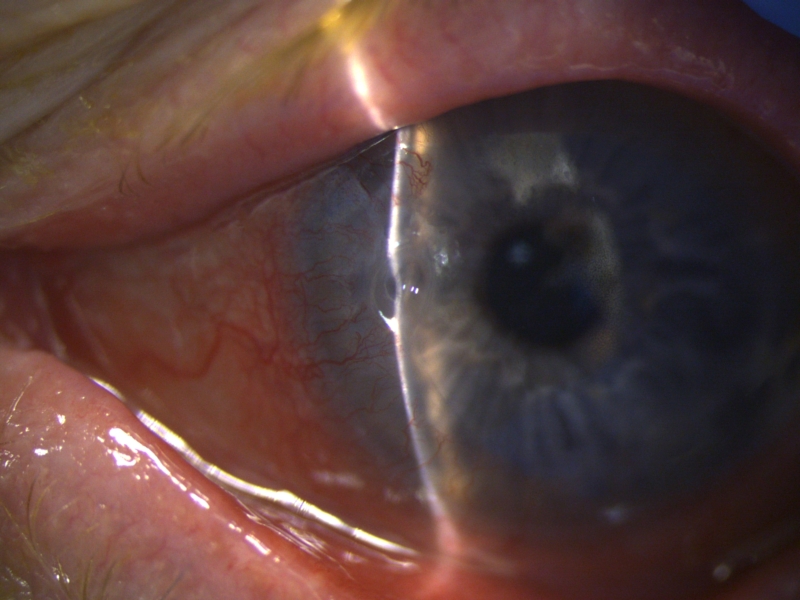

The classic clinical signs of PUK include peripheral crescentic ulceration, superimposed epithelial defect, stromal loss, and limbal infiltrates with an overhanging edge (see Image. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis in Rheumatoid Arthritis). When PUK is associated with a systemic disease, the inflammation may also involve the surrounding conjunctiva, episclera, and sclera, with additional nodular or necrotizing scleritis. Persistent inflammation and stromal lysis can progress to corneal perforation, and iris tissue is clinically visible as a "plug" at the perforation site. Perforation is an ocular emergency. Chronic PUK with peripheral thinning and corneal vascularization results in significant irregular astigmatism, scarring, and reduced vision.

Mooren ulcer arises from an unknown cause. Please refer to the Etiology section for descriptions of the 3 types of Mooren ulcer by Watson et al.

A detailed clinical history and physical examination can identify most causes of PUK. Information to note during history taking includes associated constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, as well as gastrointestinal, respiratory, skin, cardiac, and neurological signs and symptoms.

Clinical History

Patients often report sudden onset of pain, redness, photophobia, and tearing in the affected eye(s). A history of autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, GPA, or SLE, is common. The progression may be rapid, leading to corneal thinning. A history of recent eye infections, autoimmune disorders, or previous ocular surgeries may increase the risk for PUK. Although less common, trauma and contact lens overuse predispose to peripheral corneal ulceration.[31]

Physical Examination

The hallmark finding in PUK is peripheral corneal thinning, often with associated ulceration. The lesion usually affects the peripheral 2 to 4 mm of the cornea. Severe limbal and conjunctival hyperemia (redness), inflammation, and scleral involvement may be observed. Signs of impending corneal perforation may be seen in advanced cases, with visible Descemet membrane or prolapse of intraocular contents. Gray-white stromal infiltrates may be adjacent to the thinning area, suggesting active inflammation. Anterior uveitis or hypopyon may be present in severe cases, indicating a significant inflammatory response.

Associated Findings

In some cases, patients may also have accompanying scleritis or episcleritis, which can signal underlying systemic vasculitis. While unilateral PUK is more common, patients with systemic autoimmune diseases may present with bilateral involvement.[32]

Importance of Systemic Evaluation

Given PUK's strong association with systemic conditions, a thorough systemic history is essential to identify any underlying diseases that may need treatment alongside the ocular condition. A thorough history and physical examination can provide significant insights into the cause of PUK and guide appropriate management and intervention.[33]

Evaluation

A well-structured physical examination can yield clues to the systemic cause of PUK. Findings of subcutaneous nodules in the upper and lower limbs, combined with rheumatoid factor and serum autoantibody detection, characterize rheumatoid arthritis. A saddle nose appearance and auricular pinnae deformity suggest relapsing polychondritis. This recurrent inflammatory disease of unknown etiology produces selective destructive inflammatory lesions of cartilaginous structures.[34]

Features of SLE include oropharyngeal mucosal ulcers, a malar facial rash, facial and scalp hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation, and alopecia. A temporal headache with jaw claudication is often reported in giant cell arteritis. Raynaud phenomena may manifest in SLE, Sjögren syndrome, and progressive systemic sclerosis. GPA usually presents in the 4th or 5th decade, with a male preponderance of 3:2. The characteristic triad of necrotizing, granulomatous, and vasculitic lesions occurs in the respiratory tract and kidneys, causing focal segmental glomerulonephritis.[35]

Several laboratory and radiographic tests are recommended to diagnose PUK, assess corneal damage, and identify underlying systemic diseases. Commonly employed tests recommended by national and international guidelines include the following:

- Laboratory tests: Important components to note in the autoimmune panel include ANA, rheumatoid factor, and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA). These markers help diagnose autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and SLE. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are elevated in systemic vasculitis and other autoimmune diseases associated with PUK. ANCA testing can help diagnose vasculitides like GPA.[36]

- Microbiological testing: If infection is suspected, corneal scrapings with bacterial, fungal, and viral cultures can help identify the pathogen involved. Viruses such as herpes simplex and varicella zoster may be detected using polymerase chain reaction.[37]

- Imaging studies: Chest radiography may reveal hilar lymphadenopathy or lung involvement in patients with systemic causes, such as sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Sinus and orbital computed tomography is useful in cases of systemic granulomatous diseases, such as GPA.[38]

- Ocular investigations: Anterior segment optical coherence tomography helps measure the depth of corneal thinning and assess the extent of corneal damage. Corneal topography assesses peripheral corneal irregularities and thinning.[39] Ultrasound biomicroscopy is useful in anterior segment evaluation, especially if deep corneal or scleral involvement is suspected.

National and International Guidelines

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends an interprofessional approach involving ophthalmologists, rheumatologists, and infectious disease specialists. The European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons provides guidelines for early detection and management of systemic autoimmune associations.

Treatment / Management

Medical Management: Aims and Strategy

A tailored approach is best, aiming to restore epithelial integrity, halt further stromal lysis, and prevent superinfections. PUK with confirmed noninfectious etiology may be managed with a combination of topical lubricants, oral steroids, and collagenase inhibitors. The role of topical corticosteroids is controversial. These agents can increase the risk of corneal perforation in patients with autoimmune disease and should thus be considered cautiously.

Systemic immunosuppressants can take 4 to 6 weeks to take effect, but oral steroids may be prescribed in the interim. Localized or systemic infection should be treated with the appropriate antimicrobials. Corneal scrapings should be taken at the initial presentation for gram staining and microbiological evaluation. Empirical therapy, such as 4th-generation fluoroquinolone monotherapy for bacterial keratitis, should be initiated afterward. Therapy may be adjusted as needed once sensitivities are identified.

Topical steroids may be started to reduce the local inflammatory response after clinical improvement has been observed with antimicrobial treatment. However, topical steroid use should be delayed in cases of fungal infections. Topical acyclovir or ganciclovir should be started if a herpetic cause is suspected. Systemic infection requires specific protocols and shared care with the relevant specialties.

Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated with Systemic Autoimmunity

PUK management should include therapy specific to the underlying cause. Some of these interventions are discussed below.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Current first-line management for rheumatoid arthritis includes systemic corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents like methotrexate (MTX). Topical lubricants help protect the ocular surface and encourage the epithelial healing of peripheral corneal ulcers.[40] Systemic therapy is initiated with rheumatology or immunology teams. Second-line agents include azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, which are used in severe, refractory PUK cases unresponsive to MTX.[41]

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and polyarteritis nodosa

Aggressive treatment is needed for PUK secondary to GPA or PAN. The first-line immunosuppressant agents for GPA include cyclophosphamide and systemic corticosteroids, ideally started early in the disease course. Rituximab or cyclophosphamide, with or without other agents, is the most effective in controlling inflammation in GPA-associated PUK.[42] Cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids are typically used in the remission phase, while rituximab is administered in the maintenance phase. A lack of response to cyclophosphamide warrants consideration of rituximab. GPA-associated PUK presenting with necrotizing scleritis has a particularly poor visual prognosis, as this condition is usually a sign of severe systemic vasculitis.[43]

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Foster et al have suggested that systemic vasculitis only develops in the latter stages of SLE. Systemic corticosteroids and a cytotoxic agent are used in SLE-associated PUK. SLE with evidence of systemic vasculitis has significantly higher mortality.[44]

Special Circumstances

Some patients with PUK require complex therapeutic approaches. These special circumstances are explained below.

Pediatric patients

MTX is considered a first-line immunosuppressant for pediatric patients with PUK related to systemic disease. Cyclosporine may be considered if MTX does not elicit a response. These agents should be avoided during pregnancy due to their potential teratogenicity. Oral steroids may be used cautiously in children.

Patients on existing immunosuppression regimens

Infectious etiologies should be excluded before planning further PUK treatment in these individuals. Evaluation for potential acute exacerbations of systemic disease should be initiated. A change in systemic disease status may prompt the medical team to implement a step-up or maintenance strategy. Rheumatologists or immunologists evaluate the clinical response to immunosuppression, typically 6 months from treatment initiation.

Mooren Ulcer

The diagnosis of Mooren ulcer is one of exclusion. The management strategy is a stepladder approach, with topical corticosteroids and cyclosporine (0.05% to 2%) initially, then progressing to limbal conjunctival resection or excision, systemic immunosuppressants, such as oral corticosteroids, MTX, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine, and surgery, including astigmatism treatment. Surgery alone is unlikely to be curative due to the underlying autoimmune pathophysiology.[45]

An association between hepatitis C infection and a Mooren ulcer clinical phenotype has been reported.[46] Therapy with interferon-α2b is effective in treating corneal ulceration while inducing hepatic disease remission.[47]

Surgical Management

Surgery has a higher risk of PUK recurrence and graft melts. Thus, this approach should be delayed until adequate control of inflammation is achieved.[48] Graft survival is less than 50% at 6 months; hence, multiple grafts are required in many patients. Emergency surgical management depends on the indication. A therapeutic indication would be ulcers extending circumferentially, inducing corneal melt. A tectonic indication is a perforation or descemetocele. An optical indication is visual rehabilitation.

The corneal defect size determines the appropriate surgical technique. Multilayered amniotic membrane transplant and conjunctival resection, recession, or flaps may be options in areas with corneal thinning.[49] Conjunctival resection removes the tissue supplying inflammatory mediators to the cornea. Lamellar patch grafts reduce graft rejection risk compared with a full-thickness patch or tectonic grafts.[50][51] Corneal glue, ie, cyanoacrylate, with a bandage contact lens may be deployed if the perforation is less than 3 mm in diameter.[52]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PUK includes all conditions that can present as peripheral corneal thinning or opacification, as described in Table 2. In marginal keratitis, a clear cornea is often visible between the limbus and the infiltrates. Peripheral corneal degenerations are noninflammatory, have intact epithelium, and lack infiltrates.

Ruling out clinical mimics is crucial when determining the appropriate management. The following conditions should be considered:

- Mooren ulcer: A chronic, progressive, and idiopathic condition that leads to peripheral corneal ulceration and thinning similar to PUK but without systemic involvement.

- Infectious keratitis: This condition encompasses bacterial, fungal, viral, and Acanthamoeba infections. Cultures and corneal scrapings are vital to the evaluation process, as their management approaches differ significantly.

- Terrien marginal degeneration: Terrien degeneration is a noninflammatory thinning of the peripheral cornea. Unlike PUK, this condition usually lacks the overlying epithelial defect and inflammatory response.

- Scleritis-associated keratitis: Scleritis can involve the cornea in severe cases. This condition must be distinguished from primary corneal diseases like PUK, especially when associated with systemic vasculitis.

- Neurotrophic keratopathy: This condition is characterized by corneal ulceration due to reduced corneal sensation. Neurotrophic keratopathy can mimic peripheral ulceration, but it usually occurs in different regions of the cornea and lacks the autoimmune or systemic inflammatory signs of PUK.[53]

- Ocular surface disease: Conditions such as severe dry eye syndrome or limbal stem cell deficiency can lead to peripheral corneal thinning without the acute inflammatory component seen in PUK.[54]

- Rheumatoid arthritis-associated keratitis: Systemic autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis, are strongly associated with PUK. Primary corneal disease must be distinguished from secondary keratitis due to systemic conditions.

- Limbal vernal keratoconjunctivitis: This disorder can cause peripheral corneal ulcers, known as Shield ulcers, which tend to be large and oval, often involving the central cornea.[57]

- Corneal degeneration: Peripheral corneal degenerative conditions such as pellucid marginal and furrow degeneration may present with peripheral corneal thinning but lack PUK's ulcerative and inflammatory nature.[58]

- Relapsing polychondritis: A rare autoimmune condition affecting cartilage, relapsing polychondritis can cause peripheral corneal ulceration and thinning, mimicking PUK in patients with multisystem involvement.[59]

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: These conditions may present with peripheral corneal ulceration and scarring resulting from ocular surface damage, especially in severe cases.[60]

- Limbal stem cell deficiency: This condition can lead to peripheral corneal thinning and ulcers due to failure of corneal epithelial regeneration. However, limbal stem cell deficiency generally presents with more chronic, diffuse corneal surface changes.[61]

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis: This systemic vasculitis can lead to peripheral corneal ulceration and should be considered in cases of PUK with systemic manifestations like sinusitis and lung involvement.[62]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: SLE can cause peripheral corneal involvement similar to PUK, particularly in active systemic disease. Differentiation is critical for systemic management.[63]

- Sarcoidosis: This condition can involve the eye, including the cornea, leading to keratitis or corneal thinning that mimics PUK, particularly in cases with systemic granulomatous involvement.[64]

Recognizing the broad spectrum of conditions that can mimic PUK is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Each condition requires a different therapeutic approach, particularly in the presence of systemic involvement. A comprehensive history, clinical evaluation, and diagnostic tests, such as blood work and imaging, are critical to differentiate PUK from similar corneal conditions. Proper clinical, microbiological, and, sometimes, histopathological examinations are essential to differentiate between causes of PUK. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical for appropriate treatment and prevention of complications such as corneal perforation.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Key Historical Studies

Research has shown that systemic immunosuppressive therapy, eg, methotrexate or azathioprine administration, improves outcomes in autoimmune-related PUK by reducing recurrence rates. Meanwhile, numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of corticosteroids in controlling local inflammation and preventing corneal perforation in noninfectious PUK.[65]

Trials Investigating Biologics

Ongoing trials explore the use of antitumor necrosis factor-α agents like infliximab and adalimumab in cases of rheumatoid arthritis-associated PUK. Trials with drugs such as tocilizumab, which blocks the interleukin-6 receptor, are being conducted to determine their ability to control severe, refractory cases of autoimmune PUK.

Radiation Therapy in Ocular Inflammatory Diseases

The efficacy of low-dose radiation therapy for managing severe, sight-threatening ocular inflammation has been investigated. Research has shown mixed results but is worth exploring in chronic, unresponsive cases.[66]

Corneal Grafting and Limbal Stem Cell Research

Newer techniques in corneal grafting and advancements in limbal stem cell transplantation for long-term vision restoration in patients with PUK have been gaining attention.[67]

The evidence from these trials helps guide treatment decisions, particularly in severe or refractory cases of PUK where conventional therapies may not be effective. These studies also offer promising avenues for future treatment strategies, improving patient outcomes and minimizing complications.

Treatment Planning

Treatment planning for PUK involves an interprofessional approach to managing the local corneal pathology and any underlying systemic autoimmune conditions. The essential components include the following:

- Local management

- Initial treatment involves topical corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents to control inflammation.

- Antibiotic drops may be necessary to prevent or treat secondary infections.

- Surgical interventions, such as tissue glue or keratoplasty, may be needed to address corneal thinning or perforation.[68]

- Systemic immunosuppression

- The choice of immunosuppressive therapy (eg, corticosteroids, methotrexate, and azathioprine) depends on the severity of the systemic autoimmune disease.

- Long-term maintenance therapy may be necessary to prevent recurrence.[69]

- Collaboration with rheumatologists

- Collaboration with rheumatologists is crucial for systemic disease management since PUK is often associated with autoimmune diseases.

- Adjusting systemic immunosuppressive therapy is often required to control both ocular and systemic symptoms.[70]

- Regular monitoring

- Ongoing monitoring through regular ophthalmic exams and systemic workups ensures local and systemic control, helping to prevent complications like corneal perforation.

This plan allows for comprehensive management of ocular and systemic PUK involvement.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Toxicity and adverse events from managing PUK are primarily related to the systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to control the underlying autoimmune disease. An outline of potential toxicities and their management is provided below.

- Corticosteroids

- Toxicity: Prolonged use can lead to cataract formation, glaucoma, and systemic effects such as hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, and adrenal suppression.

- Management: Regular intraocular pressure checks, monitoring blood glucose levels, and tapering steroids when appropriate are typical strategies. Using topical steroids with the lowest effective dose can mitigate systemic side effects.[71]

- Methotrexate

- Toxicity: Liver toxicity, bone marrow suppression, and lung toxicity are potential concerns with long-term use of this drug.

- Management: Regular blood tests can help monitor liver function and complete blood counts. Folic acid supplementation is often used to reduce toxicity. Pulmonary function tests may also be required.[72]

- Cyclophosphamide

- Toxicity: Hemorrhagic cystitis, bone marrow suppression, increased risk of infections, and secondary malignancies are risks.

- Management: The standard approach includes hydration, using mesna to prevent bladder toxicity, regular blood work, and infection prophylaxis where appropriate.[73]

- Azathioprine

- Toxicity: Adverse effects include bone marrow suppression, liver toxicity, and increased infection risk.

- Management: The usual strategies include regular blood counts, liver function tests, and dose adjustments based on tolerance and side effects.[74]

- Biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

- Toxicity: These agents increase the risk of infections, including tuberculosis, and potential infusion reactions.

- Management: The standard approach includes screening for tuberculosis before initiating therapy, monitoring for signs of infection, and managing infusion reactions with premedication if necessary.[75]

In summary, toxicity management involves regular monitoring through laboratory work, dose adjustments, and appropriate prophylactic measures to mitigate the risks of long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

Staging

PUK is not typically classified into formal stages. However, this condition can be categorized based on the severity of corneal involvement and systemic disease activity. Below is a practical way of staging this condition:

- Mild stage: This stage involves localized peripheral corneal ulceration, with the lesion's extent limited to less than 2 to 3 clock hours. The ulceration does not penetrate deeply into the stroma, and signs of impending perforation are absent. The patient may present with mild-to-moderate symptoms, including redness, irritation, and tearing.

- Moderate stage: Corneal ulceration becomes more extensive, involving 3 to 5 clock hours of the peripheral cornea. Stromal thinning is moderate, but the patient may exhibit significant symptoms, including pain, photophobia, and decreased vision. The risk of corneal perforation begins to increase, and signs of greater systemic inflammatory activity or associated autoimmune disease are evident.

- Severe stage: This stage is characterized by extensive corneal damage, usually with more than 5 clock hours or circumferential involvement. Corneal thinning is significant, and the risk of perforation is high. Patients are often in severe pain, with the risk of visual loss considerably elevated. This stage is likely to require surgical intervention, eg, tissue gluing or corneal transplant. Systemic disease activity may also be at its peak, potentially warranting aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.[76]

- Perforated or complicated stage: Corneal perforation occurs if the disease is uncontrolled or progresses rapidly, requiring emergency surgical management. This stage may also involve secondary complications such as glaucoma, secondary infections, or vision loss.

Systemic staging may also be considered based on the activity of the associated autoimmune or systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or GPA.

Prognosis

PUK cases with systemic associations and late disease presentation are harder to manage and generally have higher morbidity and mortality. The combination of scleritis and PUK often bears poor ocular and systemic prognosis.

Corneal perforation results in a poor visual outcome despite response to treatment, with 65% of patients having a final vision of counting fingers or worse. Corneal perforation is associated with 1-year mortality rates of 24% for unilateral cases and 50% for bilateral cases.

The prognosis of PUK depends largely on the underlying cause, the promptness of diagnosis, and the adequacy of treatment. Below are some key points regarding the prognosis.

- Early diagnosis and treatment: The prognosis for preserving vision is generally better if PUK is diagnosed early and treated appropriately, especially if the underlying systemic disease is controlled. Delayed treatment can lead to more severe complications and visual loss.[77]

- Risk of recurrence: PUK can recur, especially if associated with systemic autoimmunity. Continuous management of the underlying disease is crucial to prevent recurrence.

- Severity of disease: The prognosis is poorer in cases complicated with corneal perforation or extensive scleral involvement. Surgical intervention like corneal transplantation or conjunctival resection may be necessary but carries risks of graft failure and further damage.[78]

- Systemic involvement: Patients with associated systemic conditions such as vasculitis or collagen vascular diseases may face a more guarded prognosis, as these conditions can cause ongoing ocular and systemic issues that complicate recovery and management.[79]

- Visual prognosis: The extent of corneal involvement significantly influences visual outcomes. Mild cases with peripheral ulceration that do not affect the central visual axis often have a better visual prognosis, while central involvement can lead to permanent visual impairment.

- Risk of corneal perforation: The risk of corneal perforation increases when ulceration progresses rapidly, worsening the prognosis. Corneal perforation may necessitate emergency surgical intervention, such as corneal gluing, patch grafts, or full-thickness corneal transplantation.[80]

- Impact of immunosuppressive therapy: The prognosis improves with systemic or corticosteroid therapy, especially in autoimmune-related PUK. Appropriate systemic treatment can prevent further disease progression and avoid complications such as perforation or loss of the eye (phthisis bulbi).

- Need for ongoing monitoring: Due to the chronic and relapsing nature of PUK, patients require long-term follow-up to monitor for recurrence or complications. Lifelong management of any associated systemic disease is critical to maintaining eye health and preventing future episodes of PUK.

- Surgical outcomes: In severe cases requiring procedures like corneal transplantation, the success rate of surgery may be influenced by the activity of the underlying systemic disease. The risk of graft rejection or failure is higher if inflammation is not well-controlled.

- Quality of life: PUK, especially in advanced or recurrent cases, can significantly affect the patient's quality of life due to chronic pain, frequent need for medical appointments, and visual impairment. Psychological and social support may be necessary for patients with severe disease.[81]

- Long-term management: For patients with autoimmune diseases, the long-term prognosis depends not only on ophthalmologic treatment but also on controlling the systemic condition. Ongoing collaboration between ophthalmologists, rheumatologists, and internists is essential to provide comprehensive care and improve long-term outcomes.

- Potential for severe complications: PUK can lead to serious complications if left untreated or inadequately managed, including severe scarring, secondary glaucoma, and even phthisis bulbi in extreme cases.[82]

Effective interprofessional management involving specialists such as ophthalmologists and rheumatologists is essential to improving the long-term prognosis of PUK.

Complications

Below are the possible complications of PUK.

- Corneal perforation: Severe inflammation can lead to corneal thinning and perforation, requiring urgent surgical intervention, such as corneal patch grafts or amniotic membrane transplantation.[83] This condition is the most serious ocular complication of PUK and may involve both eyes. Corneal perforation has a detrimental effect on final vision and can result in visual loss. The risk of mortality increases in patients with PUK due to systemic associations, particularly when perforation occurs.

- Vision loss: Chronic or untreated PUK may result in significant vision loss due to scarring, irregular astigmatism, or corneal opacity.[84]

- Secondary infections: The ulcerative nature of PUK makes the cornea more susceptible to secondary bacterial, fungal, or viral infections, complicating management and delaying healing.[85]

- Recurrence of autoimmune disease: PUK is often associated with systemic autoimmune conditions. Systemic or ocular disease may recur despite treatment, requiring ongoing immunosuppressive therapy.

- Scleral involvement: Inflammation can extend from the cornea to the sclera, leading to scleritis, which can cause intense pain, further tissue damage, and pose a significant risk to the eye's structural integrity.

- Corneal melting: Rapid stromal degradation and "melting" of the corneal tissue may occur, requiring prompt treatment to prevent perforation or further complications.[86]

- Glaucoma: Secondary glaucoma can arise from chronic inflammation or corticosteroid treatment. Glaucoma may increase intraocular pressure, potentially damaging the optic nerve.[87]

- Anterior uveitis: Inflammation in the front of the eye, ie, iritis or anterior uveitis, is commonly associated with PUK and contributes to pain, light sensitivity, and visual impairment.[88]

- Cataract formation: Long-term corticosteroid use, often needed for autoimmune conditions associated with PUK, can accelerate the development of cataracts, leading to cloudy vision.[89]

- Symblepharon formation: Severe ocular surface disease and chronic inflammation may induce the formation of adhesions between the eyelid and eyeball, also known as symblepharon, which can impair eye movement and eyelid function.[90]

- Corneal neovascularization: Chronic inflammation may lead to the growth of abnormal blood vessels into the cornea, which can cause further vision impairment and reduce corneal transparency.[91]

- Steroid-induced complications: Potential adverse effects of prolonged corticosteroid therapy include delayed wound healing, cataracts, and increased susceptibility to infections.[92]

- Chronic pain: Persistent inflammation and damage to the ocular surface can produce chronic pain, which can affect a patient’s quality of life.

- Endophthalmitis: Infection may penetrate the deeper eye structures in rare and severe cases, leading to endophthalmitis, a sight-threatening condition requiring urgent medical attention.[93]

Prevention of these complications requires prompt diagnosis, aggressive treatment, and an interprofessional approach to management.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative and rehabilitation care for PUK should include the following measures:

- Monitoring for graft rejection or failure: If a corneal graft is performed, close postoperative monitoring is necessary to detect signs of graft rejection or failure early. Frequent follow-ups with corneal specialists are recommended.

- Topical and systemic medications: Topical steroids and antibiotics should be continued to control inflammation and prevent infection, respectively. Depending on the underlying cause, immunosuppressive therapy may also be required in the long term.[94]

- Visual rehabilitation: After the acute phase is controlled, rehabilitation may involve using corrective lenses. Additional surgical interventions may be required to restore vision in some individuals.[95]

- Patient education: Educating the patient about medication adherence and recognition of the symptoms of recurrence or complications is crucial to long-term management and visual outcomes.[96]

Good postoperative and rehabilitation care improves long-term corneal health and vision in patients with PUK, with reduced risk of complications or recurrence.

Consultations

Specialists who must be involved in PUK management should include the following healthcare professionals:

- Rheumatologist: Essential for managing systemic autoimmune conditions underlying PUK to determine and adjust systemic therapy and prevent further corneal damage.[97]

- Infectious disease specialist: Should be consulted if an infectious etiology is suspected, particularly in cases with systemic presentations like syphilis, tuberculosis, and some viral illnesses.[98]

- Corneal specialist: Early involvement of an ophthalmologist specializing in corneal diseases is crucial for assessing the extent of damage and considering surgical interventions, such as corneal transplantation, if necessary.[99]

- Immunologist: Consider a consultation to evaluate the patient’s immune status and provide recommendations on immunosuppressive therapies when conventional treatment fails to control the autoimmune aspects of PUK.[100]

Interprofessional consultations ensure comprehensive care for managing PUK's ocular and systemic aspects.

Deterrence and Patient Education

PUK is an ophthalmic emergency, as patients are at risk of corneal perforation and blindness.[101] An interprofessional approach to investigation and management is required, involving collaboration between several specialists. The long-term need for immunosuppression may produce adverse side effects. Relapses can occur. A clear management plan and good patient communication are necessary for safe outcomes.

Deterrence measures and concepts to emphasize during patient education should include the following:

- Importance of early detection: Educate patients with autoimmune diseases about the early signs of PUK, such as eye redness, pain, and vision changes, to ensure prompt medical attention.[102]

- Systemic disease management: Emphasize the need for proper control of underlying systemic conditions through regular follow-up with rheumatologists to reduce the risk of ocular complications like PUK.[103]

- Compliance with treatment: Stress the importance of adherence to prescribed immunosuppressive or corticosteroid therapy to prevent disease progression and avoid corneal perforation.[104]

- Regular eye examinations: Patients with known systemic diseases should undergo regular ophthalmologic evaluations to detect early signs of corneal involvement before symptoms worsen.

Providing clear and proactive education can help patients avoid severe outcomes and improve their long-term eye health.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pearls

- Early diagnosis is crucial for preventing corneal perforation and permanent vision loss.

- Systemic associations, especially autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, should always be considered when diagnosing and managing PUK.

- Interprofessional care involving ophthalmology and rheumatology improves patient outcomes by addressing local and systemic factors.

Disposition

- Patients with severe PUK, especially if associated with systemic disease, require hospitalization or close outpatient follow-up for frequent monitoring and adjustment of therapy.

- Discharge planning should ensure patients have clear medication adherence and follow-up care instructions, particularly when systemic immunosuppressive therapy is involved.[105]

Pitfalls

- Delayed initiation of appropriate immunosuppressive therapy can lead to rapid progression, corneal thinning, and perforation.

- Misdiagnosis as simple infectious keratitis can occur if systemic evaluation is not performed, potentially leading to ineffective treatment and complicated PUK.

Prevention

- Early screening and treatment of ocular inflammation can prevent progression to PUK in at-risk populations, such as patients with autoimmune diseases.

- Appropriate patient education on recognizing early symptoms such as redness, pain, and vision changes can lead to timely treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

PUK can be a diagnostic challenge. Patients with this condition may exhibit no systemic symptoms or signs that point to the underlying cause and require an interprofessional team consisting of an ophthalmologist, rheumatologist, dermatologist, internist, neurologist, pharmacist, nursing staff, and technicians. Significant visual loss warrants coordination with the eye clinic liaison staff, and sight impairment registration will need to be undertaken. The etiology of PUK requires meticulous clinical investigation. Patient education should touch up on treatment compliance and the potential side effects of immunosuppressants, including corticosteroids. During prolonged treatment and monitoring of disease activity, shared care with internists and rheumatologists can last for years after the initial diagnosis.

Enhancing healthcare team outcomes for PUK requires coordinated efforts and strategic approaches from an interprofessional team. The following are key considerations:

- Skills and strategy

- Diagnosis and assessment: Ophthalmologists and optometrists must accurately diagnose PUK through clinical examination, slit-lamp microscopy, and appropriate imaging or biopsy when needed.

- Pharmacological management: Pharmacists and physicians collaborate on the appropriate selection and dosage of immunosuppressive agents, corticosteroids, and antibiotics.

- Surgical interventions: Surgeons may need to address severe cases by performing a reparative procedure, such as corneal transplantation.

- Ongoing monitoring: Nurses and advanced practitioners help with routine monitoring, ensuring patient adherence to treatment, and identifying early signs of complications.[106]

- Ethical and team responsibilities

- Patient-centered care: All team members should ensure that the patient is informed and involved in decision-making and that care plans respect the patient's preferences and values.

- Interprofessional communication: Effective communication between the healthcare providers ensures timely treatment adjustments and coordinated care.

- Interprofessional approach: Collaboration between ophthalmologists, rheumatologists, and, possibly, dermatologists ensures systemic causes of PUK are managed comprehensively.

- Outcome evaluation: Regular assessment of patient progress, both in terms of clinical healing and quality of life, is essential to ensure that care remains optimal and evidence-based.[107]

These combined efforts result in enhanced patient outcomes, reduced complications, and better team performance in managing PUK.

Review Questions

References

- 1.

- Kate A, Basu S. Systemic Immunosuppression in Cornea and Ocular Surface Disorders: A Ready Reckoner for Ophthalmologists. Semin Ophthalmol. 2022 Apr 03;37(3):330-344. [PubMed: 34423717]

- 2.

- Sharma N, Sinha G, Shekhar H, Titiyal JS, Agarwal T, Chawla B, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB. Demographic profile, clinical features and outcome of peripheral ulcerative keratitis: a prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;99(11):1503-8. [PubMed: 25935428]

- 3.

- Gupta Y, Kishore A, Kumari P, Balakrishnan N, Lomi N, Gupta N, Vanathi M, Tandon R. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021 Nov-Dec;66(6):977-998. [PubMed: 33657431]

- 4.

- Foo VHX, Mehta J, Chan ASY, Ong HS. Case Report: Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis in Systemic Solid Tumour Malignancies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:907285. [PMC free article: PMC9193368] [PubMed: 35712100]

- 5.

- Hassanpour K, H ElSheikh R, Arabi A, R Frank C, M Elhusseiny A, K Eleiwa T, Arami S, R Djalilian A, Kheirkhah A. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis: A Review. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2022 Apr-Jun;17(2):252-275. [PMC free article: PMC9185208] [PubMed: 35765625]

- 6.

- Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;33(4):835-54, vii. [PMC free article: PMC2212596] [PubMed: 18037120]

- 7.

- Yagci A. Update on peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:747-54. [PMC free article: PMC3363308] [PubMed: 22654502]

- 8.

- Artaechevarria Artieda J, Estébanez-Corrales N, Sánchez-Pernaute O, Alejandre-Alba N. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis in a Patient with Bilateral Scleritis: Medical and Surgical Management. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep-Dec;11(3):500-506. [PMC free article: PMC7588678] [PubMed: 33173497]

- 9.

- Cao Y, Zhang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhou H. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated with Autoimmune Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:7298026. [PMC free article: PMC5530438] [PubMed: 28785483]

- 10.

- Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Hoang-Xuan T, Foster CS. An analysis of therapeutic decision making regarding immunosuppressive chemotherapy for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 1990 Jan;9(1):66-73. [PubMed: 2297997]

- 11.

- Srinivasan M, Zegans ME, Zelefsky JR, Kundu A, Lietman T, Whitcher JP, Cunningham ET. Clinical characteristics of Mooren's ulcer in South India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 May;91(5):570-5. [PMC free article: PMC1954782] [PubMed: 17035269]

- 12.

- Watson PG. Management of Mooren's ulceration. Eye (Lond). 1997;11 ( Pt 3):349-56. [PubMed: 9373475]

- 13.

- McKibbin M, Isaacs JD, Morrell AJ. Incidence of corneal melting in association with systemic disease in the Yorkshire Region, 1995-7. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999 Aug;83(8):941-3. [PMC free article: PMC1723151] [PubMed: 10413698]

- 14.

- Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS, Baltatzis S. Ocular characteristics and disease associations in scleritis-associated peripheral keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002 Jan;120(1):15-9. [PubMed: 11786052]

- 15.

- Timlin HM, Hall HN, Foot B, Koay P. Corneal perforation from peripheral ulcerative keratopathy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: epidemiological findings of the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep;102(9):1298-1302. [PubMed: 29246891]

- 16.

- Sangwan VS, Zafirakis P, Foster CS. Mooren's ulcer: current concepts in management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1997 Mar;45(1):7-17. [PubMed: 9475006]

- 17.

- Cooper GS, Stroehla BC. The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2003 May;2(3):119-25. [PubMed: 12848952]

- 18.

- Angum F, Khan T, Kaler J, Siddiqui L, Hussain A. The Prevalence of Autoimmune Disorders in Women: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2020 May 13;12(5):e8094. [PMC free article: PMC7292717] [PubMed: 32542149]

- 19.

- Vadasz Z, Haj T, Kessel A, Toubi E. Age-related autoimmunity. BMC Med. 2013 Apr 04;11:94. [PMC free article: PMC3616810] [PubMed: 23556986]

- 20.

- Miller FW. The increasing prevalence of autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases: an urgent call to action for improved understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Curr Opin Immunol. 2023 Feb;80:102266. [PMC free article: PMC9918670] [PubMed: 36446151]

- 21.

- Robin JB, Schanzlin DJ, Verity SM, Barron BA, Arffa RC, Suarez E, Kaufman HE. Peripheral corneal disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986 Jul-Aug;31(1):1-36. [PubMed: 3529467]

- 22.

- Medeiros CS, Santhiago MR. Corneal nerves anatomy, function, injury and regeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2020 Nov;200:108243. [PubMed: 32926895]

- 23.

- Müller LJ, Pels E, Schurmans LR, Vrensen GF. A new three-dimensional model of the organization of proteoglycans and collagen fibrils in the human corneal stroma. Exp Eye Res. 2004 Mar;78(3):493-501. [PubMed: 15106928]

- 24.

- Coelho P, Menezes C, Gonçalves R, Rodrigues P, Seara E. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated with HCV-Related Cryoglobulinemia. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2017;2017:9461937. [PMC free article: PMC5529636] [PubMed: 28785498]

- 25.

- Riley GP, Harrall RL, Watson PG, Cawston TE, Hazleman BL. Collagenase (MMP-1) and TIMP-1 in destructive corneal disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Eye (Lond). 1995;9 ( Pt 6):703-18. [PubMed: 8849537]

- 26.

- Messmer EM, Foster CS. Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999 Mar-Apr;43(5):379-96. [PubMed: 10340557]

- 27.

- Lin YY, Jean YH, Lee HP, Lin SC, Pan CY, Chen WF, Wu SF, Su JH, Tsui KH, Sheu JH, Sung PJ, Wen ZH. Excavatolide B Attenuates Rheumatoid Arthritis through the Inhibition of Osteoclastogenesis. Mar Drugs. 2017 Jan 06;15(1) [PMC free article: PMC5295229] [PubMed: 28067799]

- 28.

- Byrd LB, Gurnani B, Martin N. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Feb 12, 2024. Corneal Ulcer. [PubMed: 30969511]

- 29.

- Mayadas TN, Tsokos GC, Tsuboi N. Mechanisms of immune complex-mediated neutrophil recruitment and tissue injury. Circulation. 2009 Nov 17;120(20):2012-24. [PMC free article: PMC2782878] [PubMed: 19917895]

- 30.

- Ellenberg D, Azar DT, Hallak JA, Tobaigy F, Han KY, Jain S, Zhou Z, Chang JH. Novel aspects of corneal angiogenic and lymphangiogenic privilege. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010 May;29(3):208-48. [PMC free article: PMC3685179] [PubMed: 20100589]

- 31.

- Hashmi MF, Gurnani B, Benson S. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jan 26, 2024. Conjunctivitis. [PubMed: 31082078]

- 32.

- Schonberg S, Stokkermans TJ. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 7, 2023. Episcleritis. [PubMed: 30521217]

- 33.

- Shah R, Amador C, Tormanen K, Ghiam S, Saghizadeh M, Arumugaswami V, Kumar A, Kramerov AA, Ljubimov AV. Systemic diseases and the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2021 Mar;204:108455. [PMC free article: PMC7946758] [PubMed: 33485845]

- 34.

- Diaz MJ, Natarelli N, Wei A, Rechdan M, Botto E, Tran JT, Forouzandeh M, Plaza JA, Kaffenberger BH. Cutaneous Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Diagnosis and Treatment. J Pers Med. 2023 Oct 10;13(10) [PMC free article: PMC10608460] [PubMed: 37888090]

- 35.

- García-Ríos P, Pecci-Lloret MP, Oñate-Sánchez RE. Oral Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Sep 21;19(19) [PMC free article: PMC9565705] [PubMed: 36231212]

- 36.

- Castro C, Gourley M. Diagnostic testing and interpretation of tests for autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Feb;125(2 Suppl 2):S238-47. [PMC free article: PMC2832720] [PubMed: 20061009]

- 37.

- Cabrera-Aguas M, Khoo P, Watson SL. Infectious keratitis: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022 Jul;50(5):543-562. [PMC free article: PMC9542356] [PubMed: 35610943]

- 38.

- Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Isaac S, Boussel L, Calender A, Androdias G, Valeyre D, El Jammal T. Sarcoidosis: A Clinical Overview from Symptoms to Diagnosis. Cells. 2021 Mar 31;10(4) [PMC free article: PMC8066110] [PubMed: 33807303]

- 39.

- Lucchino L, Mastrogiuseppe E, Giovannetti F, Bruscolini A, Marenco M, Lambiase A. Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography for the Tailored Treatment of Mooren's Ulcer: A Case Report. J Clin Med. 2024 Sep 11;13(18) [PMC free article: PMC11432291] [PubMed: 39336871]

- 40.

- Watanabe R, Ishii T, Yoshida M, Takada N, Yokokura S, Shirota Y, Fujii H, Harigae H. Ulcerative keratitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the modern biologic era: a series of eight cases and literature review. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 Feb;20(2):225-230. [PubMed: 26179634]

- 41.

- Messmer EM, Foster CS. Destructive corneal and scleral disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Medical and surgical management. Cornea. 1995 Jul;14(4):408-17. [PubMed: 7671613]

- 42.

- Ebrahimiadib N, Modjtahedi BS, Roohipoor R, Anesi SD, Foster CS. Successful Treatment Strategies in Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis-Associated Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis. Cornea. 2016 Nov;35(11):1459-1465. [PubMed: 27362884]

- 43.

- Gu J, Zhou S, Ding R, Aizezi W, Jiang A, Chen J. Necrotizing scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with Wegener's granulomatosis. Ophthalmol Ther. 2013 Dec;2(2):99-111. [PMC free article: PMC4108142] [PubMed: 25135810]

- 44.

- Foster CS, Forstot SL, Wilson LA. Mortality rate in rheumatoid arthritis patients developing necrotizing scleritis or peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Effects of systemic immunosuppression. Ophthalmology. 1984 Oct;91(10):1253-63. [PubMed: 6514289]

- 45.

- Lal I, Shivanagari SB, Ali MH, Vazirani J. Efficacy of conjunctival resection with cyanoacrylate glue application in preventing recurrences of Mooren's ulcer. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;100(7):971-975. [PubMed: 26553919]

- 46.

- Gangaputra SS, Newcomb CW, Joffe MM, Dreger K, Begum H, Artornsombudh P, Pujari SS, Daniel E, Sen HN, Suhler EB, Thorne JE, Bhatt NP, Foster CS, Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Levy-Clarke GA, Kempen JH., SITE Cohort Research Group. Comparison Between Methotrexate and Mycophenolate Mofetil Monotherapy for the Control of Noninfectious Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 Dec;208:68-75. [PMC free article: PMC6889035] [PubMed: 31344346]

- 47.

- Matoba AY, Wilhelmus KR, Jones DB. Epstein-Barr viral stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1986 Jun;93(6):746-51. [PubMed: 3737121]

- 48.

- Maeno A, Naor J, Lee HM, Hunter WS, Rootman DS. Three decades of corneal transplantation: indications and patient characteristics. Cornea. 2000 Jan;19(1):7-11. [PubMed: 10632000]

- 49.

- Feder RS, Krachmer JH. Conjunctival resection for the treatment of the rheumatoid corneal ulceration. Ophthalmology. 1984 Feb;91(2):111-5. [PubMed: 6709325]

- 50.

- Gupta N, Sachdev R, Tandon R. Sutureless patch graft for sterile corneal melts. Cornea. 2010 Aug;29(8):921-3. [PubMed: 20508506]

- 51.

- Bessant DA, Dart JK. Lamellar keratoplasty in the management of inflammatory corneal ulceration and perforation. Eye (Lond). 1994;8 ( Pt 1):22-8. [PubMed: 8013714]

- 52.

- Al-Qahtani B, Asghar S, Al-Taweel HM, Jalaluddin I. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis: Our challenging experience. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jul;28(3):234-8. [PMC free article: PMC4181453] [PubMed: 25278804]

- 53.

- Feroze KB, Patel BC. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 8, 2023. Neurotrophic Keratitis. [PubMed: 28613758]

- 54.

- Haagdorens M, Van Acker SI, Van Gerwen V, Ní Dhubhghaill S, Koppen C, Tassignon MJ, Zakaria N. Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency: Current Treatment Options and Emerging Therapies. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:9798374. [PMC free article: PMC4691643] [PubMed: 26788074]

- 55.

- Al Arfaj K, Al Zamil W. Spontaneous corneal perforation in ocular rosacea. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010 Apr;17(2):186-8. [PMC free article: PMC2892139] [PubMed: 20616930]

- 56.

- Gurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Kaur K, Moutappa F. Corneal Perforation Secondary to Rosacea Keratitis Managed with Excellent Visual Outcome. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jan;14(27):162-167. [PubMed: 35996914]

- 57.

- Kaur K, Gurnani B. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 11, 2023. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. [PubMed: 35015458]

- 58.

- Sahu J, Raizada K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 28, 2023. Pellucid Marginal Corneal Degeneration. [PubMed: 32965985]

- 59.

- Borgia F, Giuffrida R, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Relapsing Polychondritis: An Updated Review. Biomedicines. 2018 Aug 02;6(3) [PMC free article: PMC6164217] [PubMed: 30072598]

- 60.

- Labib A, Milroy C. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): May 8, 2023. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. [PubMed: 34662044]

- 61.

- Le Q, Xu J, Deng SX. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul Surf. 2018 Jan;16(1):58-69. [PMC free article: PMC5844504] [PubMed: 29113917]

- 62.

- Kubaisi B, Abu Samra K, Foster CS. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's disease): An updated review of ocular disease manifestations. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016 May;5(2):61-9. [PMC free article: PMC4869584] [PubMed: 27195187]

- 63.

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Goyal A, Varacallo M. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 4, 2023. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. [PubMed: 30571026]

- 64.

- Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 25, 2023. Ocular Sarcoidosis. [PubMed: 35593845]

- 65.

- Elsgaard S, Danielsen AK, Thyssen JP, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Drug survival of systemic immunosuppressive treatments for atopic dermatitis in a long-term pediatric cohort. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021 Dec;7(5Part B):708-715. [PMC free article: PMC8714597] [PubMed: 35028369]

- 66.

- Nuzzi R, Trossarello M, Bartoncini S, Marolo P, Franco P, Mantovani C, Ricardi U. Ocular Complications After Radiation Therapy: An Observational Study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3153-3166. [PMC free article: PMC7555281] [PubMed: 33116366]

- 67.

- Elhusseiny AM, Soleimani M, Eleiwa TK, ElSheikh RH, Frank CR, Naderan M, Yazdanpanah G, Rosenblatt MI, Djalilian AR. Current and Emerging Therapies for Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2022 Mar 31;11(3):259-268. [PMC free article: PMC8968724] [PubMed: 35303110]

- 68.

- Suwan-Apichon O, Reyes JM, Herretes S, Vedula SS, Chuck RS. Topical corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy for bacterial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD005430. [PMC free article: PMC4374569] [PubMed: 17943856]

- 69.

- Wiseman AC. Immunosuppressive Medications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Feb 05;11(2):332-43. [PMC free article: PMC4741049] [PubMed: 26170177]

- 70.

- Corbitt K, Nowatzky J. Inflammatory eye disease for rheumatologists. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023 May 01;35(3):201-212. [PMC free article: PMC10461883] [PubMed: 36943695]

- 71.

- Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 3, 2023. Corticosteroid Adverse Effects. [PubMed: 30285357]

- 72.

- Hamed KM, Dighriri IM, Baomar AF, Alharthy BT, Alenazi FE, Alali GH, Alenazy RH, Alhumaidi NT, Alhulayfi DH, Alotaibi YB, Alhumaidan SS, Alhaddad ZA, Humadi AA, Alzahrani SA, Alobaid RH. Overview of Methotrexate Toxicity: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Cureus. 2022 Sep;14(9):e29518. [PMC free article: PMC9595261] [PubMed: 36312688]

- 73.

- Varma PP, Subba DB, Madhoosudanan P. CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE INDUCED HAEMORRHAGIC CYSTITIS (A Case Report). Med J Armed Forces India. 1998 Jan;54(1):59-60. [PMC free article: PMC5531247] [PubMed: 28775418]

- 74.

- Horning K, Schmidt C. Azathioprine-Induced Rapid Hepatotoxicity. J Pharm Technol. 2014 Feb;30(1):18-20. [PMC free article: PMC5990130] [PubMed: 34860888]

- 75.

- Zhang Z, Fan W, Yang G, Xu Z, Wang J, Cheng Q, Yu M. Risk of tuberculosis in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2017 Mar 22;7(3):e012567. [PMC free article: PMC5372052] [PubMed: 28336735]

- 76.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 11, 2023. Bacterial Keratitis. [PubMed: 34662023]

- 77.

- Heidari B. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Early diagnosis and treatment outcomes. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011 Winter;2(1):161-70. [PMC free article: PMC3766928] [PubMed: 24024009]

- 78.

- Stamate AC, Tătaru CP, Zemba M. Emergency penetrating keratoplasty in corneal perforations. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2018 Oct-Dec;62(4):253-259. [PMC free article: PMC6421488] [PubMed: 30891520]

- 79.

- Shanmugam VK, Angra D, Rahimi H, McNish S. Vasculitic and autoimmune wounds. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Mar;5(2):280-292. [PMC free article: PMC5319730] [PubMed: 28214498]

- 80.

- Ting DSJ, Cairns J, Gopal BP, Ho CS, Krstic L, Elsahn A, Lister M, Said DG, Dua HS. Risk Factors, Clinical Outcomes, and Prognostic Factors of Bacterial Keratitis: The Nottingham Infectious Keratitis Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:715118. [PMC free article: PMC8385317] [PubMed: 34458289]

- 81.

- Gurnani B, Czyz CN, Mahabadi N, Havens SJ. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 11, 2023. Corneal Graft Rejection. [PubMed: 30085585]

- 82.

- Van Bentum RE, Van den Berg JM, Wolf SE, Van der Bijl J, Tan HS, Verbraak FD, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Multidisciplinary management of auto-immune ocular diseases in adult patients by ophthalmologists and rheumatologists. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;99(2):e164-e170. [PMC free article: PMC7984222] [PubMed: 32749781]

- 83.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K, Venugopal A, Srinivasan B, Bagga B, Iyer G, Christy J, Prajna L, Vanathi M, Garg P, Narayana S, Agarwal S, Sahu S. Pythium insidiosum keratitis - A review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022 Apr;70(4):1107-1120. [PMC free article: PMC9240499] [PubMed: 35325996]

- 84.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K, Agarwal S, Lalgudi VG, Shekhawat NS, Venugopal A, Tripathy K, Srinivasan B, Iyer G, Gubert J. Pythium insidiosum Keratitis: Past, Present, and Future. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022 Oct;11(5):1629-1653. [PMC free article: PMC9255487] [PubMed: 35788551]

- 85.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 11, 2023. Therapeutic Keratoplasty. [PubMed: 37276297]

- 86.

- Gurnani B, Narayana S, Christy J, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Successful management of pediatric pythium insidiosum keratitis with cyanoacrylate glue, linezolid, and azithromycin: Rare case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022 Sep;32(5):NP87-NP91. [PubMed: 33779337]

- 87.

- Christy J, Jain N, Gurnani B, Kaur K. Twinkling Eye -A Rare Presentation in Neovascular Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2019 May 23; [PubMed: 31135586]

- 88.

- Paulbuddhe V, Addya S, Gurnani B, Singh D, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Where Do We Currently Stand on Treatment Strategies? Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4201-4218. [PMC free article: PMC8542579] [PubMed: 34707340]

- 89.

- Gupta P, Gurnani B, Patel BC. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 8, 2024. Pediatric Cataract. [PubMed: 34283446]

- 90.

- Venugopal A, Gurnani B, Ravindran M, Uduman MS. Management of symblepharon with Gore-tex as a novel treatment option for ocular chemical burns. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2024 Nov;34(6):1865-1874. [PubMed: 38444229]

- 91.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jun 11, 2023. Contact Lens–Related Complications. [PubMed: 36512659]

- 92.

- Kaur K, Gurnani B, Devy N. Atypical optic neuritis - a case with a new surprise every visit. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2020;10:Doc11. [PMC free article: PMC7113617] [PubMed: 32269909]

- 93.

- Gurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Retrospective multifactorial analysis of Pythium keratitis and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 May;69(5):1095-1101. [PMC free article: PMC8186601] [PubMed: 33913840]

- 94.

- Gabros S, Nessel TA, Zito PM. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 10, 2023. Topical Corticosteroids. [PubMed: 30422535]

- 95.

- van Nispen RM, Virgili G, Hoeben M, Langelaan M, Klevering J, Keunen JE, van Rens GH. Low vision rehabilitation for better quality of life in visually impaired adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 27;1(1):CD006543. [PMC free article: PMC6984642] [PubMed: 31985055]

- 96.

- Cross AJ, Elliott RA, Petrie K, Kuruvilla L, George J. Interventions for improving medication-taking ability and adherence in older adults prescribed multiple medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 May 08;5(5):CD012419. [PMC free article: PMC7207012] [PubMed: 32383493]

- 97.

- Amador-Patarroyo MJ, Jalil-Florencia E, Otero-Marquez O, Molano-Gonzalez N, Mantilla RD, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM, Barraquer-Coll C. Can Appropriate Systemic Treatment Help Protect the Cornea in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis? A Multidisciplinary Approach to Autoimmune Ocular Involvement. Cornea. 2018 Feb;37(2):235-241. [PMC free article: PMC5768223] [PubMed: 29176449]

- 98.

- Parikh V, Tucci V, Galwankar S. Infections of the nervous system. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2012 May;2(2):82-97. [PMC free article: PMC3401822] [PubMed: 22837896]

- 99.

- Maghsoudlou P, Sood G, Gurnani B, Akhondi H. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Feb 24, 2024. Cornea Transplantation. [PubMed: 30969512]

- 100.

- Rosenblum MD, Gratz IK, Paw JS, Abbas AK. Treating human autoimmunity: current practice and future prospects. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Mar 14;4(125):125sr1. [PMC free article: PMC4061980] [PubMed: 22422994]

- 101.

- Willmann D, Fu L, Melanson SW. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 17, 2023. Corneal Injury. [PubMed: 29083785]

- 102.

- Glover K, Mishra D, Singh TRR. Epidemiology of Ocular Manifestations in Autoimmune Disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:744396. [PMC free article: PMC8593335] [PubMed: 34795665]

- 103.

- Radu AF, Bungau SG. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview. Cells. 2021 Oct 23;10(11) [PMC free article: PMC8616326] [PubMed: 34831081]

- 104.

- Khan M, Michelson S, Newman-Casey PA, Woodward MA. Medication Adherence Among Patients With Corneal Diseases. Cornea. 2021 Dec 01;40(12):1554-1560. [PMC free article: PMC8418623] [PubMed: 33661137]

- 105.

- Lee SY, Kim KH, Kim T, Kim SM, Kim JW, Han C, Song JY, Paik JW. Outpatient Follow-Up Visit after Hospital Discharge Lowers Risk of Rehospitalization in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Psychiatry Investig. 2015 Oct;12(4):425-33. [PMC free article: PMC4620298] [PubMed: 26508952]

- 106.

- Kampik A. Imaging in ophthalmology and need for slit-lamp and ophthalmoscopy examinations. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2016 May-Aug;9(2):79. [PMC free article: PMC4932799] [PubMed: 27433032]

- 107.

- Babiker A, El Husseini M, Al Nemri A, Al Frayh A, Al Juryyan N, Faki MO, Assiri A, Al Saadi M, Shaikh F, Al Zamil F. Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudan J Paediatr. 2014;14(2):9-16. [PMC free article: PMC4949805] [PubMed: 27493399]

Disclosure: Lanxing Fu declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Sophie Jones declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Figures

Tables

Table 1. Causes of PUK

|

Systemic Causes |

Ocular Causes |

|

Infection:

Autoimmune:

Other Systemic:

|

Infection:

Autoimmune:

Trauma:

Neurological:

Iatrogenic:

|

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis

| Inflammatory | Noninflammatory |

|

Staphylococcal marginal keratitis Phlyctenulosis Vernal keratoconjunctivitis Infectious keratitis Exposure keratitis Trichiasis Lid malpositions |

Terrien marginal degeneration Pellucid marginal degeneration Senile furrows |