This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

Continuing Education Activity

Microcytic, hypochromic anemia, as the name suggests, is the type of anemia in which the circulating RBCs are smaller than the usual size of RBCs (microcytic) and have decreased red color (hypochromic). The most common cause of this type of anemia is decreased iron reserves of the body which may be due to multiple reasons. This may be due to decreased iron in the diet, poor absorption of iron from the gut, acute and chronic blood loss, increased demand for iron in certain situations like pregnancy or recovering from major trauma or surgery. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of Microcytic, hypochromic anemia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the recognition and management of this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the recommended management of microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

- Outline the typical presentation for a patient with microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

- Review the pathophysiology of microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

Introduction

Anemia is defined as the reduction in circulating red-cell mass below normal levels. Anemia is a very common condition that is widespread in the human population. Circulating red blood cells (RBCs) contain a protein known as hemoglobin, that protein has four polypeptide chains and one heme ring that contains iron in reduced form. Iron is the main component of hemoglobin and is the prime carrier of oxygen. Decreased iron reserves in the body affect the production of hemoglobin which, subsequently hinders the transport of oxygen to organ systems of the body. Anemia reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and leads to tissue hypoxia. Usually, it is diagnosed by hematocrit (the ratio of packed RBCs to blood volume) and the hemoglobin concentration.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Microcytic, hypochromic anemia, as the name suggests, is the type of anemia in which the circulating RBCs are smaller than the usual size of RBCs (microcytic) and have decreased red color (hypochromic). The most common cause of this type of anemia is decreased iron reserves of the body which may be due to multiple reasons. This may be due to decreased iron in the diet, poor absorption of iron from the gut, acute and chronic blood loss, increased demand for iron in certain situations like pregnancy or recovering from major trauma or surgery.

Epidemiology

According to epidemiologic data from World Health Organization (WHO), 24.8% of the human population is currently suffering from anemia out of which a major portion is due to iron deficiency anemia. Hypochromic microcytic anemia is more common in premenopausal females because they lose blood with each menstrual cycle. Among the female population, almost 41% of all pregnant females suffer from anemia while among nonpregnant pre-menopausal females 30% of females are struggling with anemia. The male population is usually resistant to anemia due to circulating testosterone levels. However, 12.7% of adult males are also globally afflicted with anemia. After the female population, pre-school-aged children suffer the most from anemia because of a lack of iron in their primary diet. Human milk contains 0.3 mg/L iron which does not provide enough iron. On the other hand, cow milk contains double the amount of iron, but that iron has poor bioavailability.[5]

Pathophysiology

An adult human being requires 1 mg to 2 mg per day of iron. The normal western diet contains approximately 10 mg to 20 mg of iron. Iron from animal sources is in the form of Haeme iron which has a bioavailability of 10% to 20% compared to non-heme iron which has a limited bioavailability of 1% to 5%. The cause of low non-heme iron bioavailability is due to its interactions with tannins, phosphates, and other food constituents. An average male contains 6grams of iron while a female contains 2.5 gm of iron. This diet is usually sufficient to maintain a healthy iron pool. Ingested iron is freed from other food constituents by gastric HCL while ascorbic acid (vitamin C) prevents precipitation of ferric. Iron is subsequently absorbed from the duodenum and upper parts of the jejunum through an iron transporter called ( ferroportin) while transferrin protein carries this iron in the blood. Iron is stored in the form of ferritin a ubiquitous iron protein that is found predominantly in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and skeletal muscles. In the liver, it is stored in parenchymal cells while in other tissues it is stored in macrophages. This process of iron absorption from the gut is controlled by hepcidin, a protein that regulates the amount of iron absorbed from the diet.

Hypochromic microcytic anemia is caused by any factor which reduces the body's iron stores. Hemoglobin is a globular protein that is a major component of RBCs it is manufactured in the bone marrow by erythroid progenitor cells. It has four globin chains two of which are alpha-globin chains while the other two are beta-globin chains, these four chains are attached to a porphyrin ring (heme) the center of which contains iron in the form of ferrous (reduced iron) capable of binding four molecules of oxygen. Reduced iron stores halt the production of hemoglobin chains, and its concentration begins to decrease in the newly formed RBCs since the red color of RBCs is due to hemoglobin the color of the newly formed RBCs begins to fade thus the name, hypochromic. As the newly produced RBCs contain less amount of hemoglobin, they are of relatively small size when compared to normal RBCs, thus the name, microcytic.

Iron deficiency hypochromic microcytic anemia is caused due to disruption of iron supply in diet due to decreased iron content in the diet, pathology of the small intestines like sprue and chronic diarrhea, gastrectomy, and deficiency of vitamin C in the diet. It may be due to acute or chronic blood loss and also due to suddenly increased demands of pregnancy or major trauma and surgery.

Reduced hemoglobin in the RBCs decreases the amount of oxygen delivered to the peripheral tissues leading to tissue hypoxia.

Histopathology

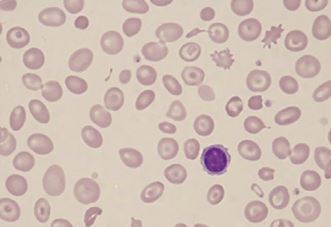

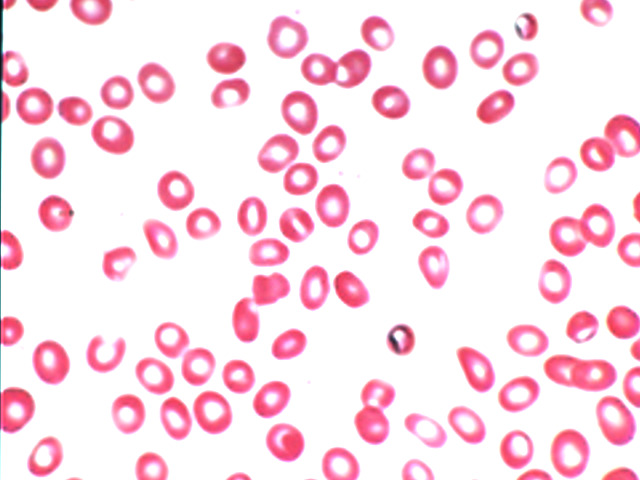

The decreased quantity of hemoglobin in the RBCs leads to a compromised size of RBCs. Normal RBCs contain a central zone of pallor, which is usually one-third of the size of RBC; however, in hypochromic microcytic anemia, that size increases, and hemoglobin is usually only present in the peripheral rim of the RBCs. The normal size of RBC is about 80 to 100 femtolitre/RBC (fl/RBC); however, in iron deficiency anemia, this size decreases below 80 fl/RBC. Normal bone marrow stored iron gives a black-blue color on reaction with Prussian blue dye but, in iron deficiency-related hypochromic microcytic anemia, that stainable iron is markedly decreased or even absent in severe cases. Poikilocytes in the form of small, elongated red cells (pencil cells) are also characteristically seen.

History and Physical

The typical history indicates:

- Reduced dietary intake of iron

- Increased blood loss in menstrual flow

- Bleeding from git, particularly from gastric and duodenal ulcers

- Malignancy or large gut

- Major trauma after which iron stores become depleted.

In some cases, pica may be present. This is a preference to eat non-nutritious substances like clay, ice, and flour.

The patient may also have complained of food stuck inside the chest due to esophageal webs along with a swollen tongue ( glossitis) this along with anemia is defined a Plummer-Vinson syndrome which is a rare manifestation of iron deficiency.

On physical exam, a patient may present with pallor evident on hands as well as conjunctivitis, tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, exhaustion, koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails). Severe anemia may also lead to the production of signs and symptoms of angina due to decreased delivery of oxygen to cardiac myocytes.

Evaluation

The first test to perform is complete blood count (CBC) which will indicate the presence of anemia after a thorough physical exam. CBC will show different RBC indices like MCV and MCHC. These parameters comment on the quantity of hemoglobin inside the RBCs they are both usually decreased in hypochromic microcytic anemia. The Next test to perform is iron studies which take a look at transferrin saturation, total iron-binding capacity, and ferritin. TIBC is usually increased in iron deficiency anemia, while transferrin saturation is markedly decreased in iron deficiency anemia. Ferritin levels below 12 ng/ml in the absence of scurvy are a reliable indicator of iron deficiency anemia. However, a low or normal ferritin level does not exclude the diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia because ferritin is an acute-phase reactant protein, and its level increase during the time of infections. As iron levels fall, transferrin levels increase in compensation.[6][7][8]

The peripheral smear will show small-sized RBCs with pencil cells. The microcytic cells will have a large zone of central pallor and a small peripheral rim of hemoglobin.

Treatment / Management

After the diagnosis of hypochromic microcytic anemia is established, iron replacement therapy can be commenced. Therapy includes 325 mg of ferrous sulfate three times a day orally. Of this, up to 10 mg of iron can be absorbed from the gut and is the preferred initial treatment. Nausea and constipation are the side effects that limit the compliance of this therapy. Compliance can be increased by gradually increasing the dose of the treatment while monitoring the patient for side effects. The maximum tolerated dose is usually selected for the replacement of lost iron. The impact of this treatment usually appears after 3 weeks, while the full effects will be evident by 2 months.[9][10][11]

Parenteral iron products may be used when:

- Oral drugs produce unrelenting side effects

- The anemia is resistant to oral therapy

- There is some git disease-preventing proper absorption of iron

- There is continued blood loss which cannot be corrected by oral supplementation.

The iron preparation with sorbitol is slowly infused over 5 minutes at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight in males and 35 mg/kg body weight in females. The parenteral dose is usually the iron deficit plus one extra gram of iron to replenish the iron reserves of the body.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of hypochromic microcytic anemia can be thalassemias, anemia of chronic disease, lead poisoning, and X-linked sideroblastic anemia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of hypochromic microcytic anemia are done with an interprofessional team that includes a primary care provider, a nurse practitioner, a gynecologist, a hematologist, a surgeon, and a gastroenterologist. The key is to find the cause of the anemia. After the diagnosis of hypochromic microcytic anemia is established, iron replacement therapy can be commenced. Therapy includes 325 mg of ferrous sulfate three times a day orally. Of this, up to 10 mg of iron can be absorbed from the gut and is the preferred initial treatment. Nausea and constipation are the side effects that limit the compliance of this therapy. Compliance can be increased by gradually increasing the dose of the treatment while monitoring the patient for side effects. The maximum tolerated dose is usually selected for the replacement of lost iron. The impact of this treatment usually appears after 3 weeks, while the full effects will be evident in 2 months. Close follow-up is required to ensure that the patient's hematocrit is improving.[12]

Review Questions

References

- 1.

- Gebreweld A, Bekele D, Tsegaye A. Hematological profile of pregnant women at St. Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Hematol. 2018;18:15. [PMC free article: PMC6038189] [PubMed: 30002836]

- 2.

- Needs T, Gonzalez-Mosquera LF, Lynch DT. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): May 1, 2023. Beta Thalassemia. [PubMed: 30285376]

- 3.

- Farashi S, Harteveld CL. Molecular basis of α-thalassemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2018 May;70:43-53. [PubMed: 29032940]

- 4.

- Warner MJ, Kamran MT. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 7, 2023. Iron Deficiency Anemia. [PubMed: 28846348]

- 5.

- Budnevsky AV, Voronina EV, Ovsyannikov ES, Tsvetikova LN, Zhusina YG, Labzhaniya NB. [ANEMIA OF CHRONIC DISEASES AS A SYSTEMIC MANIFESTATION OF CHRONIC PULMONARY OBSTRUCTIVE DISEASE]. Klin Med (Mosk). 2017;95(3):201-6. [PubMed: 30303337]

- 6.

- Buttarello M. Laboratory diagnosis of anemia: are the old and new red cell parameters useful in classification and treatment, how? Int J Lab Hematol. 2016 May;38 Suppl 1:123-32. [PubMed: 27195903]

- 7.

- Brancaleoni V, Di Pierro E, Motta I, Cappellini MD. Laboratory diagnosis of thalassemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016 May;38 Suppl 1:32-40. [PubMed: 27183541]

- 8.

- Kawabata H. [Iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2016 Feb;57(2):104-9. [PubMed: 26935626]

- 9.

- Fazal MW, Andrews JM, Thomas J, Saffouri E. Inpatient iron deficiency detection and management: how do general physicians and gastroenterologists perform in a tertiary care hospital? Intern Med J. 2017 Aug;47(8):928-932. [PubMed: 28509435]

- 10.

- Herklotz R, Risch L, Huber AR. [Hemoglobinopathies--clinical symptoms and diagnosis of thalassemia and abnormal hemoglobins]. Ther Umsch. 2006 Jan;63(1):35-46. [PubMed: 16450733]

- 11.

- Hassoun H, Pavlovsky M, Mansoor S, Stopka T. Diagnosis of polycythemia vera in an anemic patient. South Med J. 2000 Jul;93(7):710-2. [PubMed: 10923962]

- 12.

- Barlas RS, McCall SJ, Bettencourt-Silva JH, Clark AB, Bowles KM, Metcalf AK, Mamas MA, Potter JF, Myint PK. Impact of anaemia on acute stroke outcomes depends on the type of anaemia: Evidence from a UK stroke register. J Neurol Sci. 2017 Dec 15;383:26-30. [PubMed: 29246615]

Disclosure: Hammad Chaudhry declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Madhukar Reddy Kasarla declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Figures

Peripheral blood picture of beta thalassemia major patient showing hypochromic, microcytic red blood cells along with target cells. Contributed by Hamza Bajwa, MD

Hypochromic Microcytic Anemia Image courtesy S Bhimji MD